Paradigm's Latest Research: pm-AMM, a Unified Automated Market Maker Dedicated to Prediction Markets

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Paradigm's Latest Research: pm-AMM, a Unified Automated Market Maker Dedicated to Prediction Markets

AMMs and their predecessors (such as market scoring rules) were originally invented as a way to provide liquidity for prediction markets.

Authors: Ciamac Moallemi, Dan Robinson, Paradigm

Translation: Yangz, Techub News

Introduction

In this article, we introduce a new type of automated market maker (AMM) specifically designed for prediction markets: the pm-AMM.

AMMs and their predecessors (such as market scoring rules) were originally invented as a way to provide liquidity for prediction markets. Today, they dominate most DEX trading volume. Ironically, however, despite a sharp rise in prediction market trading volume, much of it relies on order books rather than AMMs.

One possible reason is that existing AMMs are poorly suited for outcome tokens—tokens that pay $1 if an event occurs and $0 otherwise. The volatility of outcome tokens depends on the current probability of the event and the time remaining until the prediction market expires, resulting in inconsistent liquidity provision. Once the market expires, liquidity providers (LPs) effectively lose all value.

To address this, we propose a novel AMM optimized around these considerations, tackling a long-standing question in AMM research: what does it mean to optimize an AMM for a specific asset class? In other words, given a model for a particular asset (e.g., options, bonds, stablecoins, or outcome tokens), how should it shape the design of our AMM? We approach this question through the lens of loss versus rebalancing (LVR).

Key Results

We develop a price dynamics model for outcome tokens, which we call Gaussian score dynamics. This model applies to prediction markets that forecast whether an underlying stochastic process—such as the point spread in a basketball game, vote margin in an election, or price of an asset—will exceed a certain threshold at a future expiration time.

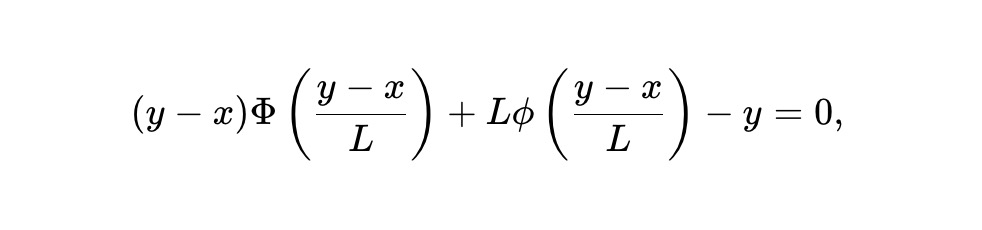

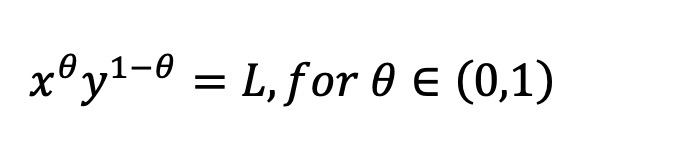

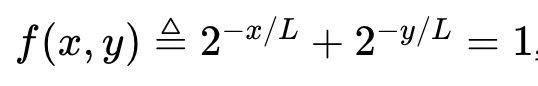

Using this model, we derive a new invariant-based AMM for such tokens: the static pm-AMM invariant:

Here, x is the reserve of the outcome token in the AMM, y is the reserve of its opposite/complementary outcome token, L is the total liquidity or scaling parameter, and ϕ and Φ denote the probability density function and cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution, respectively.

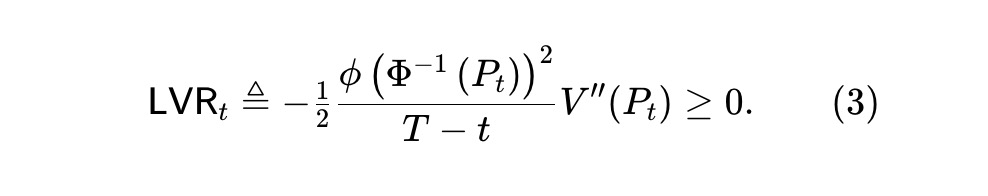

This invariant is grounded in the concept of loss versus rebalancing (LVR)—a measure of the rate at which an AMM loses value due to arbitrage. LVR depends on both the shape of the AMM and the price dynamics of the underlying asset being traded.

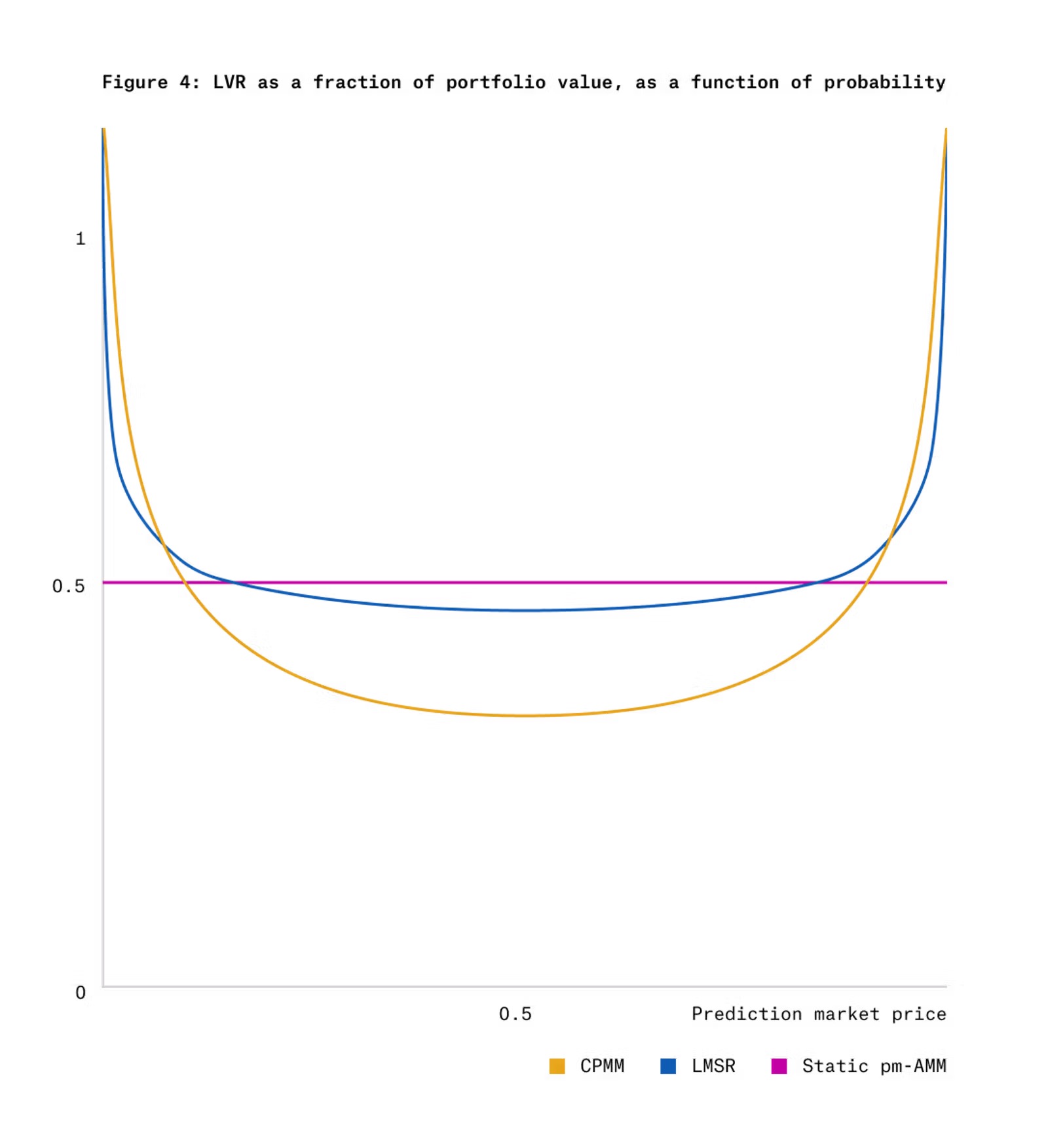

We define a uniform AMM for a given asset as one whose LVR, as a fraction of portfolio value, remains constant regardless of the current price. Milionis et al. showed that for assets following geometric Brownian motion (GBM)—a popular model for stocks and cryptocurrencies—the constant geometric mean market maker (e.g., Uniswap and Balancer) is essentially the only uniform AMM. In contrast, the static pm-AMM is the uniform AMM for assets whose behavior follows our proposed Gaussian score dynamics model for outcome tokens.

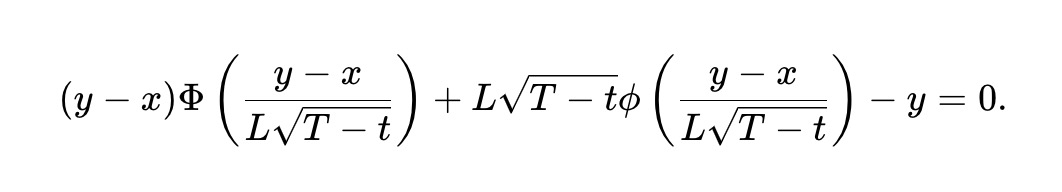

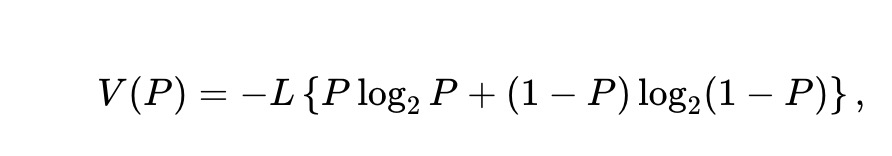

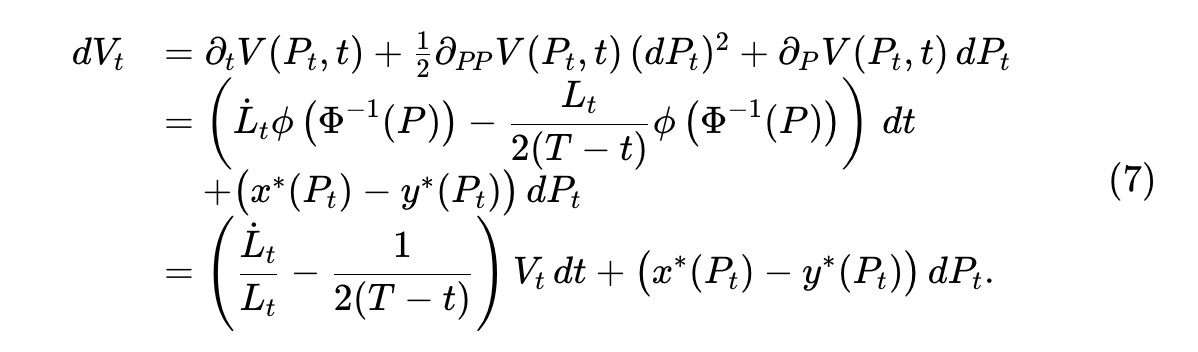

While the static pm-AMM maintains uniform LVR across all prices, the LVR still increases as the prediction market approaches expiry due to heightened volatility near expiration. To counteract this, we derive the dynamic pm-AMM invariant, which adjusts liquidity over time so that the expected LVR per unit time remains constant throughout the remaining lifetime of the market. This variant depends on the time to expiry, T−t:

The dynamic pm-AMM reduces liquidity over time to prevent LVR from increasing as expiry approaches. While this may not always be desirable in practice—since non-arbitrage trading activity (and associated fees) might increase over time—it provides LPs with a framework to adjust liquidity based on expected fee income and desired allocation of arbitrage risk.

These AMMs could help bootstrap passive liquidity on-chain for prediction markets. The concept of uniform AMMs and the methodology may also broadly benefit DEX designers seeking to tailor AMMs for assets whose price dynamics deviate from GBM, such as stablecoins, bonds, options, and other derivatives.

Figure 1 shows the invariant curves of static and dynamic pm-AMMs compared with well-known alternatives: the constant product market maker (CPMM) and the logarithmic market scoring rule (LMSR). Note that the dynamic pm-AMM offers lower liquidity over time.

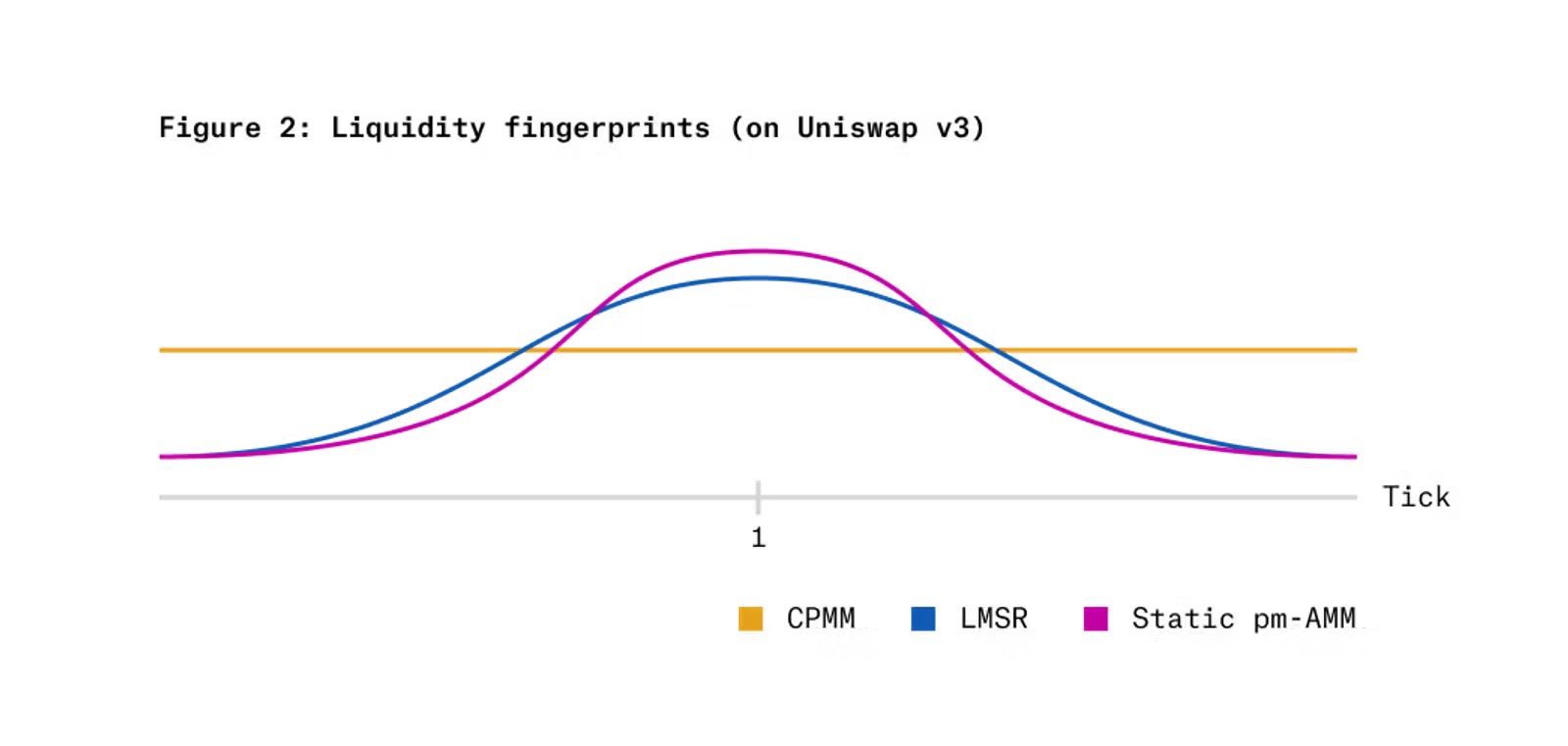

Figure 2 illustrates the "liquidity fingerprint" that would result from implementing the static pm-AMM invariant on a concentrated liquidity AMM like Uniswap v3, compared to CPMM and LMSR. The horizontal axis uses a logarithmic scale for relative price (price of token x divided by price of token y), while the vertical axis shows the liquidity provided by each AMM at that price level. As shown, pm-AMM concentrates more liquidity around a relative price of 1 (corresponding to 50% probability, or token price of $0.50) and less liquidity at extreme relative prices (very low or very high).

Background

Prediction Markets

Prediction markets are becoming increasingly popular in crypto. In October 2024 alone, Polymarket's trading volume exceeded $2 billion. Yet, most crypto prediction markets rely on order books for liquidity rather than AMMs, despite AMMs dominating most DEX trading volumes.

One reason may be that outcome tokens behave differently from conventional assets, making standard AMMs unstable. Consider a prediction market on a coin-flip game where someone flips a coin 1001 times. Two tokens, x and y, represent heads and tails outcomes. If heads outnumber tails, x pays $1 and y pays $0; otherwise, the reverse holds.

The volatility of these outcome tokens heavily depends on the number of remaining flips and the current score. The closer the score and the fewer flips left, the higher the volatility. Consequently, losses from constant product market makers (which depend on volatility, as discussed below) vary significantly over time.

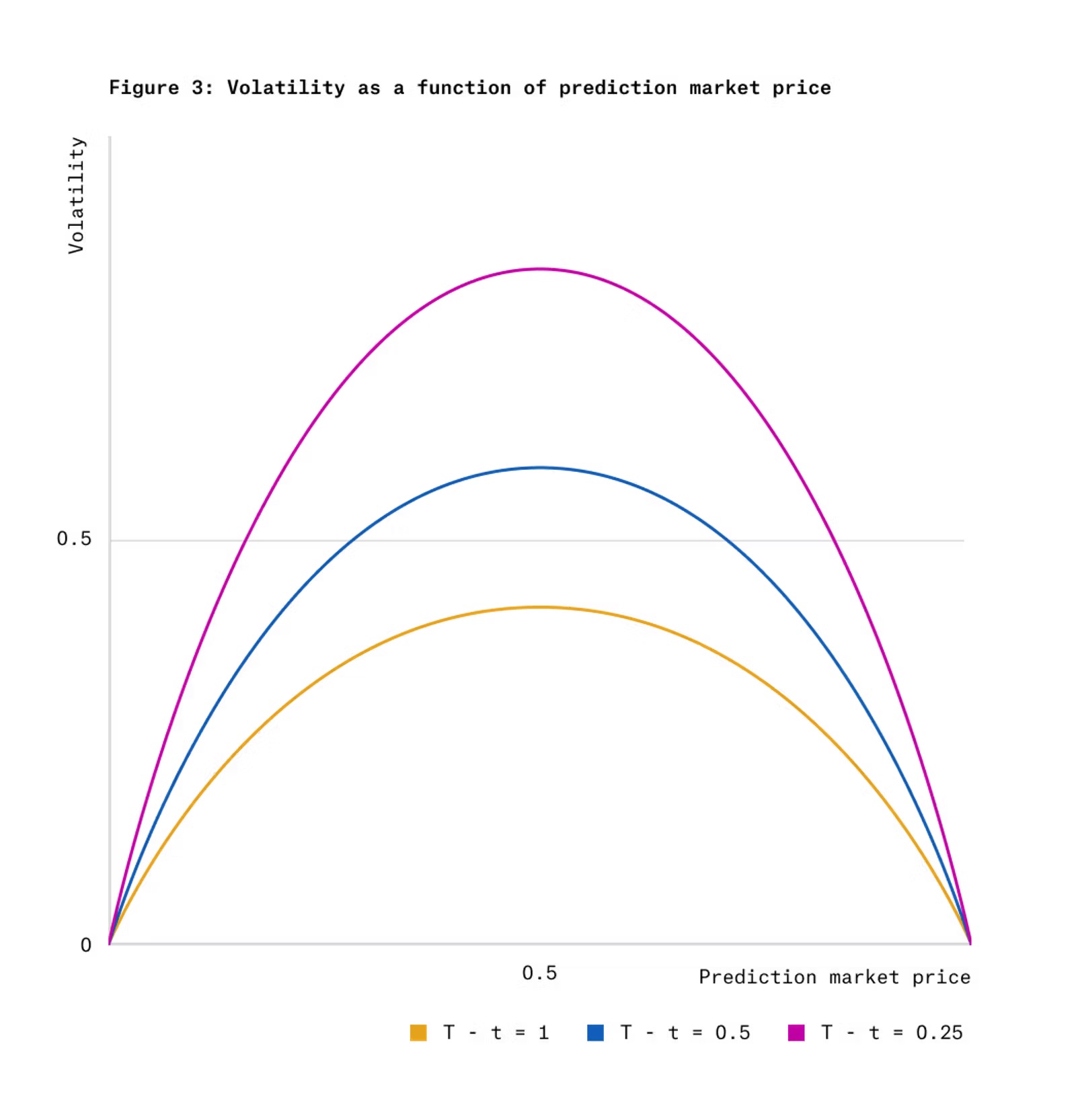

Figure 3 shows how the volatility of outcome token prices under Gaussian score dynamics varies with token price and time remaining.

Many popular prediction markets resemble this coin-flip example, betting on whether a stochastic process will end above or below zero at a future expiry time. For instance:

-

A prediction market on a basketball game expires when the game clock hits zero. The stochastic process is the point differential between the two teams.

-

A presidential election prediction market expires on election day. The process is the difference in voter support between candidates.

-

A market predicting whether Bitcoin’s price will exceed a strike price on a future date can be modeled using the log of Bitcoin’s current price minus the strike price.

The Gaussian score dynamics model we define for outcome tokens is inspired by such examples. It assumes that the market price reflects the probability that an underlying Brownian motion ends above zero. This resembles the Black-Scholes model for binary options—financial instruments that pay a fixed amount if an asset price exceeds a strike, and zero otherwise. However, in our model, the underlying process need not correspond to a tradable asset.

We make a simplifying assumption: the price of an outcome token equals the probability it will pay $1. This ignores important features such as risk and time preferences, which could be explored in future research.

Moreover, not all prediction markets fit the Gaussian score dynamics model, which assumes predictable rates of new information arrival. For example, basketball games may better fit the model than soccer matches, due to higher scoring frequency and more consistent evolution of score differences. Some prediction markets—like those forecasting whether a one-off rare event (e.g., an earthquake) will occur by a certain date—are entirely incompatible with this model. Nevertheless, the model serves as a useful starting point for deriving dynamics for other cases and demonstrates a method for deriving uniform AMMs for any given model.

Loss vs. Rebalancing and Uniformity

With this model established, we derive a mechanism potentially better suited to these tokens than existing AMMs (e.g., CPMM or LMSR). Our guiding metric is the expected loss rate for liquidity providers, formalized as "loss versus rebalancing" (LVR).

LVR captures the primary adverse selection cost of AMMs: without trading, AMM prices remain static, becoming stale as new information emerges. These stale prices are exploited by informed arbitrageurs who trade against the AMM at unfavorable prices. Thus, LVR represents the cost paid by LPs to arbitrageurs for price correction.

Additionally, in the absence of trading fees, LVR equals the loss incurred by an LP who delta-hedges their position by holding a short position equal to the pool's token holdings. Hence, LVR builds on a key insight from the Black-Scholes option pricing model: just as options eliminate market risk via delta hedging, LVR values the LP position in an AMM after removing market risk. That is, LVR isolates the unique cost of providing liquidity in an AMM, distinct from merely holding the same tokens as the pool.

We consider simple invariant-based AMMs without fees or MEV recovery mechanisms. Under such conditions, AMMs inevitably lose value to arbitrage, and no invariant can eliminate LVR (except ones that prevent trading altogether). Moreover, “minimizing” LVR lacks practical meaning, as reducing LVR simply means offering less liquidity.

However, while we cannot eliminate LVR, we can make it uniform—ensuring the percentage loss of pool value does not depend on the current asset price. We call this property uniformity.

Imagine a sponsor willing to provide zero-fee liquidity on a prediction market to surface public beliefs about an outcome. They expect to lose money but prefer losses to be evenly distributed over time and price, rather than concentrated. In this case, the pool’s current portfolio value acts as their “budget.” On a uniform AMM, investing $1 in liquidity at any time results in the same expected loss at the next time step, regardless of the pool’s state.

Uniformity also has implications for profit-seeking LPs. Even if an AMM recovers some or all LVR (via nonzero swap fees or MEV auctions), it still needs a strategy for allocating liquidity across prices and time. The expected loss in a zero-fee pool can serve as a guide for how much liquidity to allocate at a given time, incorporating the asset’s price dynamics.

We define a uniform AMM for a given asset as one whose expected LVR is a constant fraction of the pool’s current value, regardless of the asset’s current price. Note that whether an AMM has uniform LVR depends on the asset’s price process. As shown in Milionis et al. Appendix B.2, if an asset follows geometric Brownian motion, the weighted geometric mean market maker is essentially the only uniform AMM, with invariant:

This is the formula used in Balancer, with Uniswap v2’s constant product market maker as a special case. However, for tokens following Gaussian score dynamics, constant geometric mean market makers do not have uniform LVR. The same applies to the logarithmic market scoring rule (LMSR).

Figure 4 compares the LVR of CPMM and LMSR with the uniform LVR of static pm-AMM for Gaussian score dynamics outcome tokens at time T−t=1.

Given these insights, we develop two AMMs tailored for prediction markets under Gaussian score dynamics: one with uniform LVR at any given time (but increasing LVR as expiry approaches), and another with uniform LVR and constant expected loss rate over the remaining time horizon.

As seen in Figure 4, CPMM and LMSR exhibit high LVR when outcome token prices approach extremes (near 0 or 1). Although price volatility is low near these points (see Figure 3), the decay rate of pool value accelerates at extreme prices. Therefore, a uniform AMM should offer less liquidity at extreme prices—which is exactly what pm-AMM achieves (see Figure 2).

Prior Work

AMMs originated in prediction markets and market scoring rules (e.g., LMSR). These led to the discovery of constant function market makers (CFMMs), such as Uniswap v2, characterized by an invariant relationship between reserves of different assets. Such designs have become dominant mechanisms in DEXs in recent years.

Recent work applies financial economics to understand AMM costs via LVR, primarily focusing on geometric Brownian motion. In contrast, prediction markets have very different price dynamics due to bounded payoffs and finite lifetimes. Taleb proposed dynamics based on observable voting processes, while we develop an alternative based on observable Gaussian score processes.

There has been prior applied research on designing AMMs for non-GBM assets. One example is StableSwap, an AMM for stablecoin pairs based on the intuition that mean-reverting assets should concentrate liquidity around a central price—but its derivation does not involve modeling the asset price process. Another is YieldSpace, an AMM designed for zero-coupon bonds. While YieldSpace uses a simple bond pricing model, it lacks a full price process model (e.g., no modeling of interest rate evolution).

Academic work also exists on designing real-time market models based on beliefs about asset price behavior. One example is Goyal et al.’s framework, which maximizes expected active liquidity rather than equalizing expected loss, sometimes yielding opposite conclusions. For instance, they argue that LMSR (which concentrates liquidity near price 1) is suitable when LPs expect prices to stay near parity, whereas our framework suggests concentrating liquidity near 1 when prices are expected to diverge—as with outcome tokens.

AMM Models

Automated Market Makers

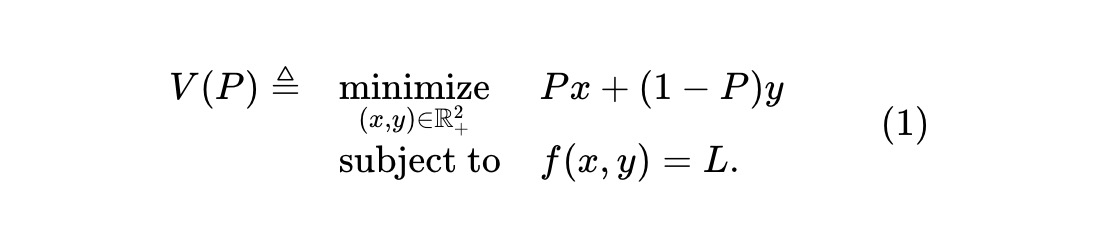

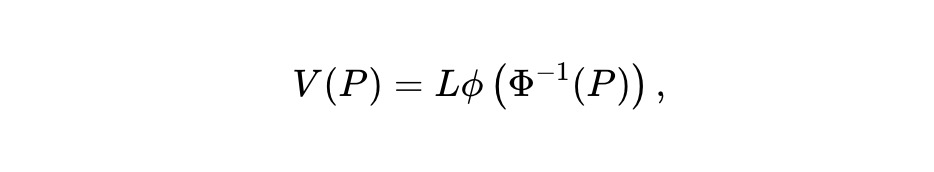

Consider a prediction market on a single event and an AMM trading two opposing assets. Let x denote the risky asset that pays $1 if the event occurs and $0 otherwise; y denotes the opposite, paying $1 if the event does not occur. The AMM maintains an invariant f(x,y)=L, where f(·,·) is the invariant function of reserves (x,y), and L is a constant. Given the price P of asset x (in USD), the pool value function is:

This gives the pool value when the price of x is P. Since holding one unit each of x and y is equivalent to holding cash, y must have price 1−P. Assume arbitrageurs observe the price Pt of x (and thus 1−Pt for y) at each time t. With no fees or frictions, they continuously monitor the AMM and exploit any mispricing. In maximizing their profits, they trade against the AMM to minimize its reserve value. Let Vt denote the reserve value at time t (when price is Pt), so Vt = V(Pt).

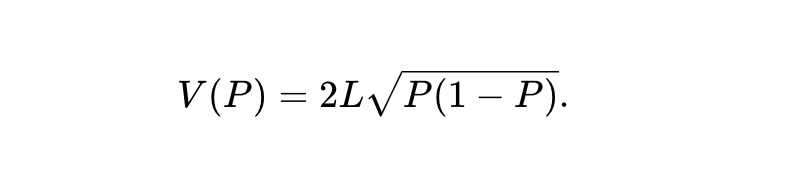

Example 1: For the constant product market maker (CPMM), the invariant is f(x,y)≜xy, and the pool value function is:

Example 2: Robin Hanson’s logarithmic market scoring rule (LMSR) corresponds to an AMM with invariant:

Its pool value function is (proportional to the binary entropy implied by the price):

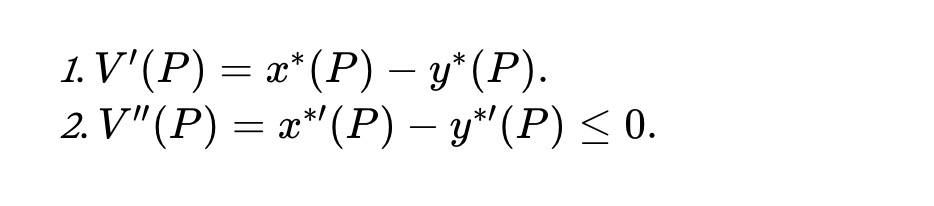

Let x∗(P) and y∗(P) denote the optimal solution to optimization problem (1), assumed to exist, be unique, and be sufficiently smooth in price P. Then the following resembles Theorem 1 in Milionis et al., adapted to this setting:

Theorem 1. For all prices P≥0, the pool value function satisfies:

Gaussian Score Dynamics

How does the risky asset price evolve over time under our Gaussian score dynamics? Specifically, assume a stochastic process {Zt} over t∈[0,T], where the event outcome is determined by the sign of Zt at expiry T: if ZT≥0, x pays out; if ZT<0, y pays out. Think of Zt as the point differential between two competing teams. We refer to Zt as the score process. Note that while our model assumes this score process exists, the AMM need not observe it directly. As discussed below, the AMM can infer the current score from the marginal price (after arbitrage) and time to expiry.

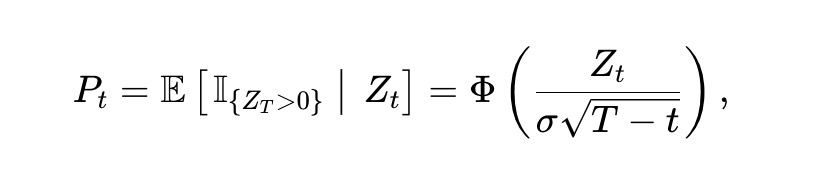

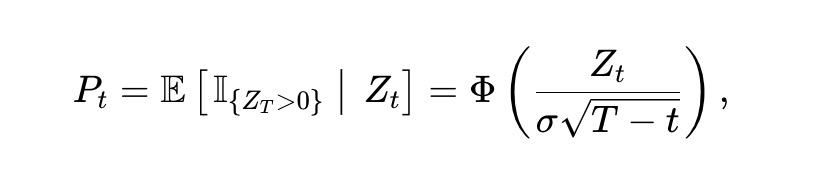

We assume Zt follows a random walk. Specifically, let Zt be a Brownian motion with volatility σ>0, i.e., dZt=σdBt, where Bt is a standard Brownian motion. Then the price Pt of asset x at time t is:

where Φ(·) is the standard normal cumulative distribution function (CDF). Applying Itô’s theorem, Pt satisfies:

where ϕ(·) is the standard normal probability density function, and Φ⁻¹(·) is the inverse CDF. Note that while the score dynamics and the mapping between score and price depend on σ, the isolated price process Pt does not. The volatility of these dynamics as a function of price and time remaining is shown in Figure 3.

Uniform AMM

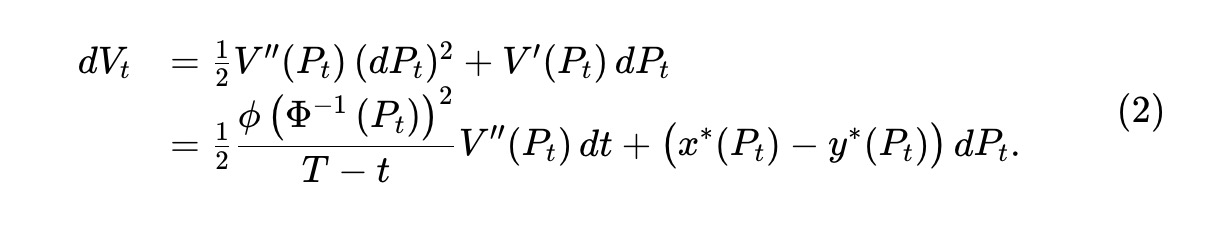

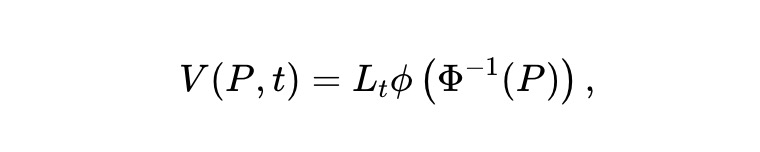

From earlier, let Vt denote the pool reserve value at time t (when price is Pt), so Vt=V(Pt). By Itô’s lemma, the change in pool value follows:

Since Pt is a martingale, the second term in (2) is also a martingale (possibly increasing or decreasing). However, due to V(·) (see Theorem 1), the first term is negative and thus a decreasing process. This is the loss-versus-rebalancing process identified by Milionis et al., capturing value lost to arbitrageurs trading against the pool at unfavorable prices. We define the instantaneous loss rate as:

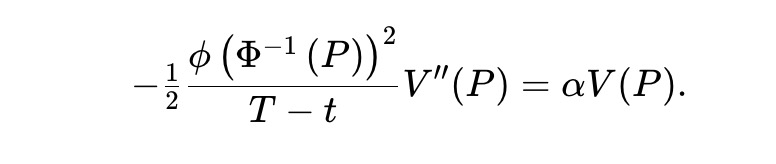

Milionis et al. found that for assets following GBM, essentially only geometric mean market makers are uniform AMMs. For prediction markets under Gaussian score dynamics, examining (3), a uniform LVR pool must solve the following ODE:

This is impossible because the left side depends on t while the right does not. The core issue is that GBM dynamics are time-invariant, whereas Gaussian score dynamics are highly time-dependent.

To resolve this, we allow α to be time-dependent: set α=β/(T−t), with β>0. Then consider:

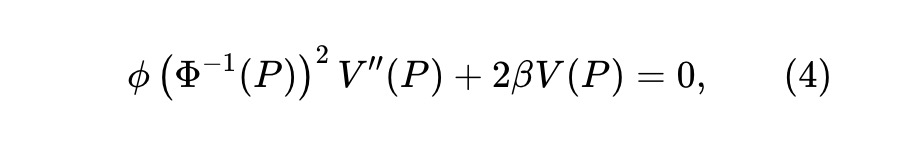

This yields an ODE valid for P≥0. Additionally, V(·) must satisfy further conditions, such as V′′(P)≤0 (see Theorem 1).

Static pm-AMM

The ODE above simplifies by changing variables to u=Φ⁻¹(P). When β=1/2, there exists a solution satisfying both the ODE and the concavity requirement:

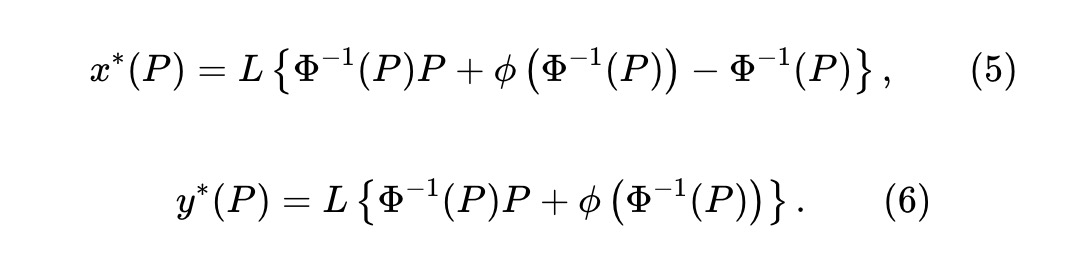

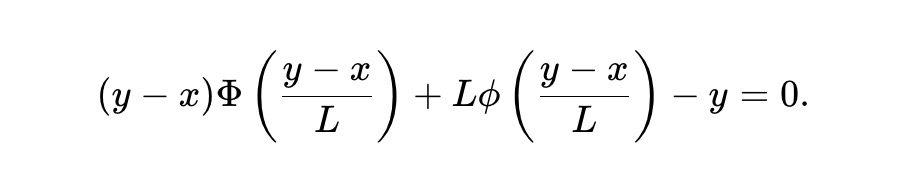

The reserves of x and y tokens are:

Here, L≥0 is a liquidity parameter scaling the pool size. Noting that y∗(P)−x∗(P)=LΦ⁻¹(P), substituting into (5) implies the reserves (x,y) must satisfy the invariant:

This defines the static pm-AMM. By construction, this AMM satisfies:

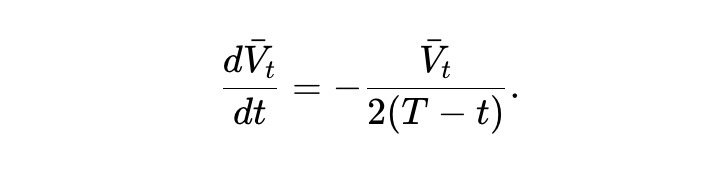

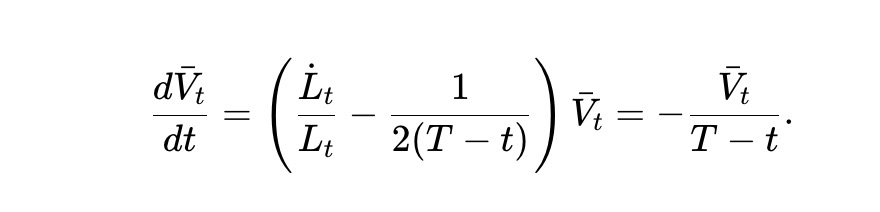

Let V̄t=E[Vt] denote the expected pool value. From (2), we get:

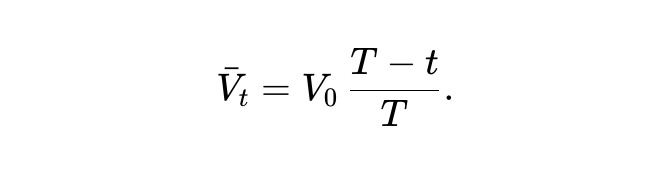

Solving this ODE yields the following: in expectation, the pool value of the static pm-AMM decays proportionally to the square root of the time remaining.

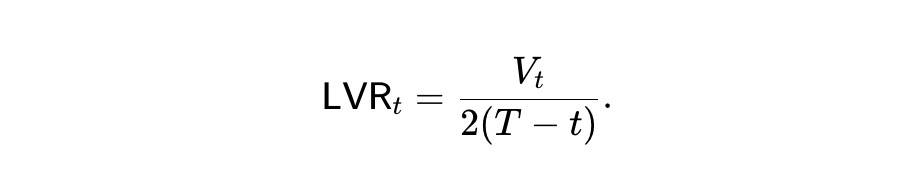

Dynamic pm-AMM

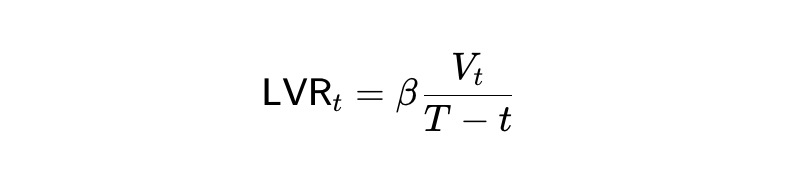

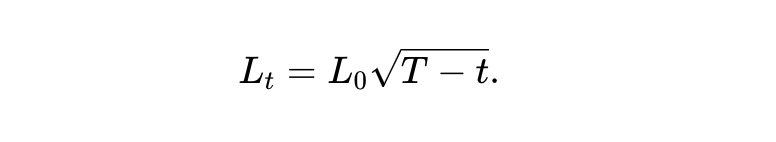

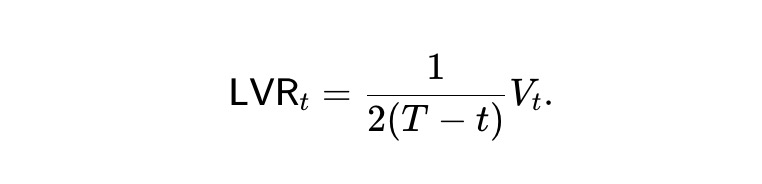

A drawback of the static pm-AMM is that while its LVR per dollar of value is uniform across prices, it changes over time. Specifically, the loss per dollar increases inversely with time to expiry, rising toward infinity as the market expires and value drops to zero.

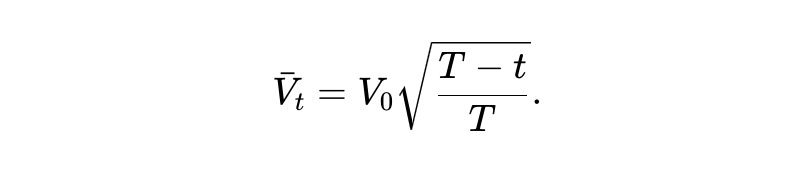

Dynamic Liquidity. We propose a time-varying version of the static pm-AMM, where LPs gradually withdraw liquidity to reduce losses. Suppose the pool value evolves as:

where Lt is a deterministic smooth function governing how liquidity is removed (or possibly added) over time. Applying Itô’s lemma to the pool value process Vt≜V(Pt,t), we get:

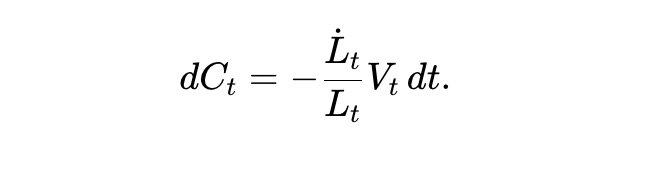

Let Ct denote the cumulative dollar value of withdrawn liquidity. Since pool value scales linearly with Lt, the dollar value of Lt changes is proportional to Vt/LT. We obtain:

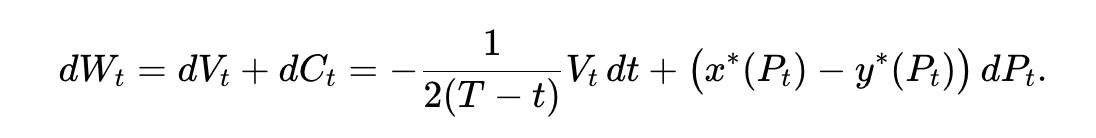

The total wealth Wt of AMM LPs consists of pool reserve value plus cumulative withdrawals: Wt=Vt+Ct, satisfying:

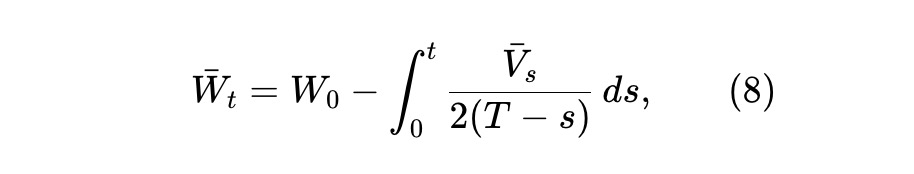

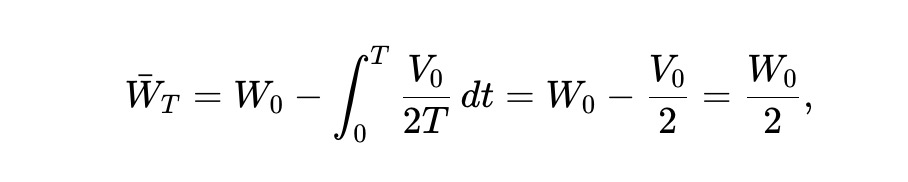

Hence, the expected LP wealth W̄t≜E[Wt] satisfies (with V̄t≜E[Vt]):

Now, consider the specific liquidity curve:

We call this the dynamic pm-AMM. From (7), the expected pool value V̄t=E[Vt] satisfies:

Solving this ODE yields:

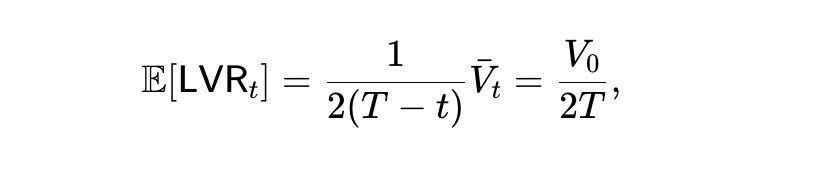

In other words, under the dynamic pm-AMM, the expected pool value declines linearly after withdrawals. Moreover, inheriting the static pm-AMM’s value function, the LVR loss rate per unit time is:

The expected loss rate remains constant over time t. That is, the dynamic pm-AMM loses value to arbitrageurs at a constant expected rate.

Finally, from (8), the expected wealth process is as shown below. Thus, half of the initial wealth is eventually lost.

Conclusion

The pm-AMM may be well-suited for prediction markets driven by dynamics similar to our Gaussian score model. More broadly, our work suggests that the concept of uniform AMMs could extend to other asset classes such as bonds, options, and derivatives.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News