Understanding Cellula: A Gameified Asset Issuance Protocol Paying Homage to POW Mining

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Understanding Cellula: A Gameified Asset Issuance Protocol Paying Homage to POW Mining

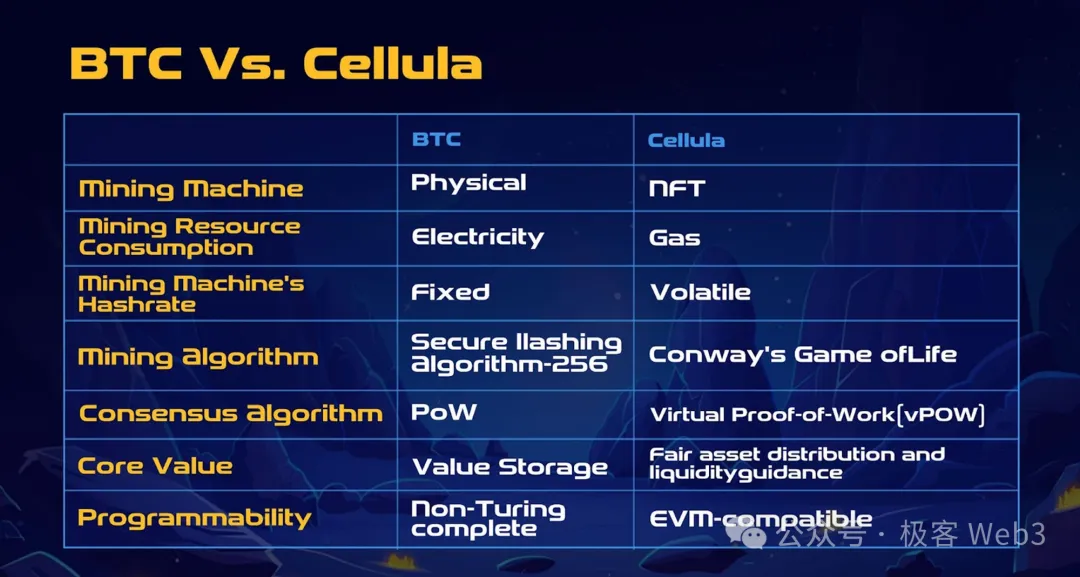

Compared to the BTC mining hardware industry, Cellula's approach is a more interesting social experiment.

Authors: Nickaqiao & Faust, Geeker Web3

Since the rise of ERC-20 assets in 2017, Web3 has entered an era of low-barrier asset issuance. Projects have freely issued custom tokens or NFTs via IDO, ICO, and similar methods, often with strong centralization or opaque information, leading to frequent Rug Pulls. These so-called "sickle" projects now clearly treat ICO and IDO as prime opportunities to harvest users.

To date, traditional IDO and ICO models have fully exposed their flaws in fairness. There's long been a desire for more equitable and reliable asset issuance protocols that can resolve various issues during new project TGEs. While some creative projects have unilaterally proposed their own "fair economic models," these rarely get generalized and promoted, ultimately becoming isolated "specific cases" rather than abstracted universal protocols.

So, what kind of model constitutes a fairer and more reliable method of asset distribution? What kind of solution could serve as a universal protocol? This article introduces Cellula—a project offering a fresh perspective on solving these problems. They've implemented a POW-like asset distribution layer using virtual Proof-of-Work (vPOW), transforming the asset distribution process into a "mining" mechanism that mimics Bitcoin’s approach to achieve a fairer asset allocation paradigm.

Although many view this project as GameFi, since in-game rewards can be configured as any token type, Cellula theoretically functions as a POW-effect asset distribution platform, opening broader prospects and imagination for Web3 asset issuance—so much so that calling it “a social experiment paying homage to BTC mining” would not be an exaggeration.

POW and vPOW: A Lottery System with Unpredictable Outcomes

Whether it’s authentic POW, POS, or today’s topic vPOW, the essence lies in designing an algorithm whose output is unpredictable or hard to predict, enabling a form of “lottery draw” based on results. Bitcoin miners must locally construct blocks meeting specific criteria and submit them to full nodes across the network for consensus validation before receiving block rewards. The criteria require the block hash to meet certain conditions—for example, starting with six zeros.

Because block hashes are inherently unpredictable, constructing valid blocks requires continuously altering input parameters to the given algorithm. This brute-force process demands significant computational power and high-end hardware from miners.

In short, BTC mining leverages the unpredictability of the SHA-256 hashing algorithm to create a global, permissionless “lottery system” in which all miners participate online. This design ensures formal permissionlessness at the cost of electricity consumption.

Moreover, POW enables fairer asset distribution. On mainstream POW public chains, it’s far harder for project teams to control supply compared to POS chains, where numerous cases of strong team-controlled allocations abound in typical POS chains, ICOs, and IDOs.

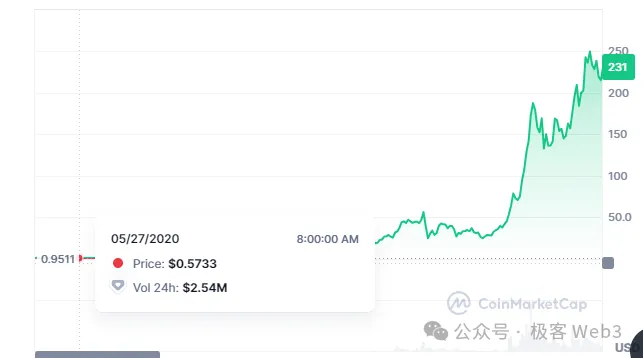

(Solana surged nearly 500x between 2020–2021 under FTX manipulation, creating a highly unfavorable environment for late-joining validator operators)

For instance, Solana’s price skyrocketed close to 1000x between 2019 and 2021 due to manipulation by FTX and SBF. Many early Solana validators were initial investors who acquired tokens at near-zero cost, severely undermining fairness in asset distribution. While project teams may still exert some control even in POW systems, the degree is generally far less severe than in POS setups.

The issue is that POW patterns are typically applied at the base-layer blockchain level, not at the DApp asset issuance layer. Can we simulate POW effects through a chain-implementable scheme? If yes, we could establish a fairer and more reliable asset distribution protocol than centralized ICO/IDO models. Combined with gaming scenarios, this could yield interesting GameFi applications (though its utility isn't limited to games—it could provide fair asset distribution frameworks for other projects).

So the key question becomes: how do we simulate POW effects at the on-chain asset issuance layer? In the GameFi project Cellula discussed here, they introduce Conway’s Game of Life algorithm to allocate computing power to virtual digital entities called “BitLife.” Think of it like people cultivating cell clusters in petri dishes—the more surviving cells over time, the higher the converted mining power and the greater the chance of earning mining rewards.

In brief, Cellula replaces traditional POW hashing computations with another computation method featuring unpredictable or hard-to-predict outcomes—effectively changing the nature of “Work” in “Proof of Work.” Under Cellula’s framework, success hinges on acquiring BitLifes with higher survival counts. Simulating BitLife state transitions consumes computational resources; essentially, BTC mining’s hash algorithm is replaced by Conway’s Game of Life simulation algorithm, termed vPOW (Virtual POW).

Next, let’s dive deeper into the mechanism design of vPOW. The details here are fascinating—indeed, one thing Cellula achieves is simulating Bitcoin’s mining rig industry model via on-chain NFT trading dynamics.

The Core of vPOW: Conway’s Game of Life and BitLife

Before diving into Cellula’s mechanism, let’s first examine the most critical component of vPOW—Conway’s Game of Life, which traces back to John von Neumann’s concept of “cellular automata” in 1950. Mathematician John Conway formally introduced “Conway’s Game of Life” in 1970, using algorithms to simulate natural evolutionary patterns of life.

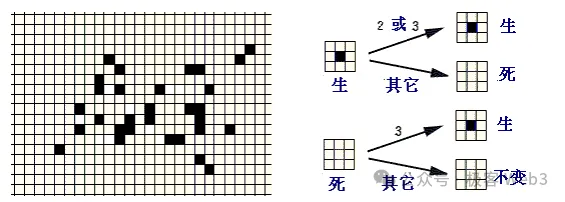

Imagine a petri dish divided into a grid of small squares. We perform an “initial setup,” placing live cells on some squares. From there, the life/death states of these cells evolve over time, gradually forming complex cell clusters (think mold reproduction). It’s essentially a two-dimensional grid game governed by simple rules:

-

Each cell has two states: alive or dead. Like Minesweeper, each cell interacts with its eight neighboring cells (black = alive, white = dead);

-

If a living cell has fewer than two live neighbors (0 or 1), it dies;

-

If a living cell has two or three live neighbors, it remains alive;

-

If a living cell has more than three live neighbors, it dies (simulating resource competition among overcrowded populations);

-

If a dead cell has exactly three live neighbors, it becomes alive (simulating reproduction)

Thus, simply put, given an initial configuration of cell states on a 2D grid, the system evolves iteratively over time according to these rules, producing highly diverse outcomes. You can even simulate computer logic using Conway’s Game of Life.

For example, each cell’s alive/dead state corresponds to binary 0/1. The initial state acts as “input parameters,” where each cell’s status represents input data. As states evolve generation by generation, each step resembles a computational operation, and the final state becomes the “output.”

With proper initial configurations, Conway’s Game of Life can produce specific outputs after several generations. Given the vast number of possible initial setups, this property can be used to simulate lottery-like randomness. We can set constraints: each player randomly selects an initial pattern, and after 100 generations, whoever’s petri dish meets certain characteristics qualifies for rewards—very similar to BTC mining:

“The system defines what kind of output qualifies. Participants feed random initial inputs into a fixed algorithm, attempting to generate qualifying outputs.” Since the number of potential input combinations is enormous (virtually astronomical), participants must expend substantial effort to have any chance of success—this is precisely the logic of proof-of-work: miners must invest real work to earn rewards.

Having grasped the basic ideas behind Cellula and Conway’s Game of Life, let’s look at its concrete implementation. Cellula divides the aforementioned “petri dish” into 9×9 = 81 cells. Each cell has two states—alive or dead—corresponding to binary 0 and 1. Thus, the total number of possible initial configurations is 2^81—an astronomically large number (roughly equal to one trillion squared).

Players’ task is selecting the initial pattern (input parameters) for their petri dish. A BitLife serves as the physical representation of the dish (in reality, an NFT), consisting of 81 cells, each holding a cell (either alive or dead; empty slots count as dead). Every 3×3 = 9 adjacent cells form a BitCell, and each BitLife comprises 2 to 9 BitCells joined together (if fewer than 9 BitCells are used, remaining areas default to dead cells).

By combinatorics, a BitCell (3×3 grid) has 2^9 possible configurations. Players randomly select multiple different BitCell patterns and combine them into a BitLife. Simply put, players pick a random initial configuration for their petri dish. With 2^81 total possibilities—an astronomical figure—the choice space is immense, akin to BTC mining using SHA-256.

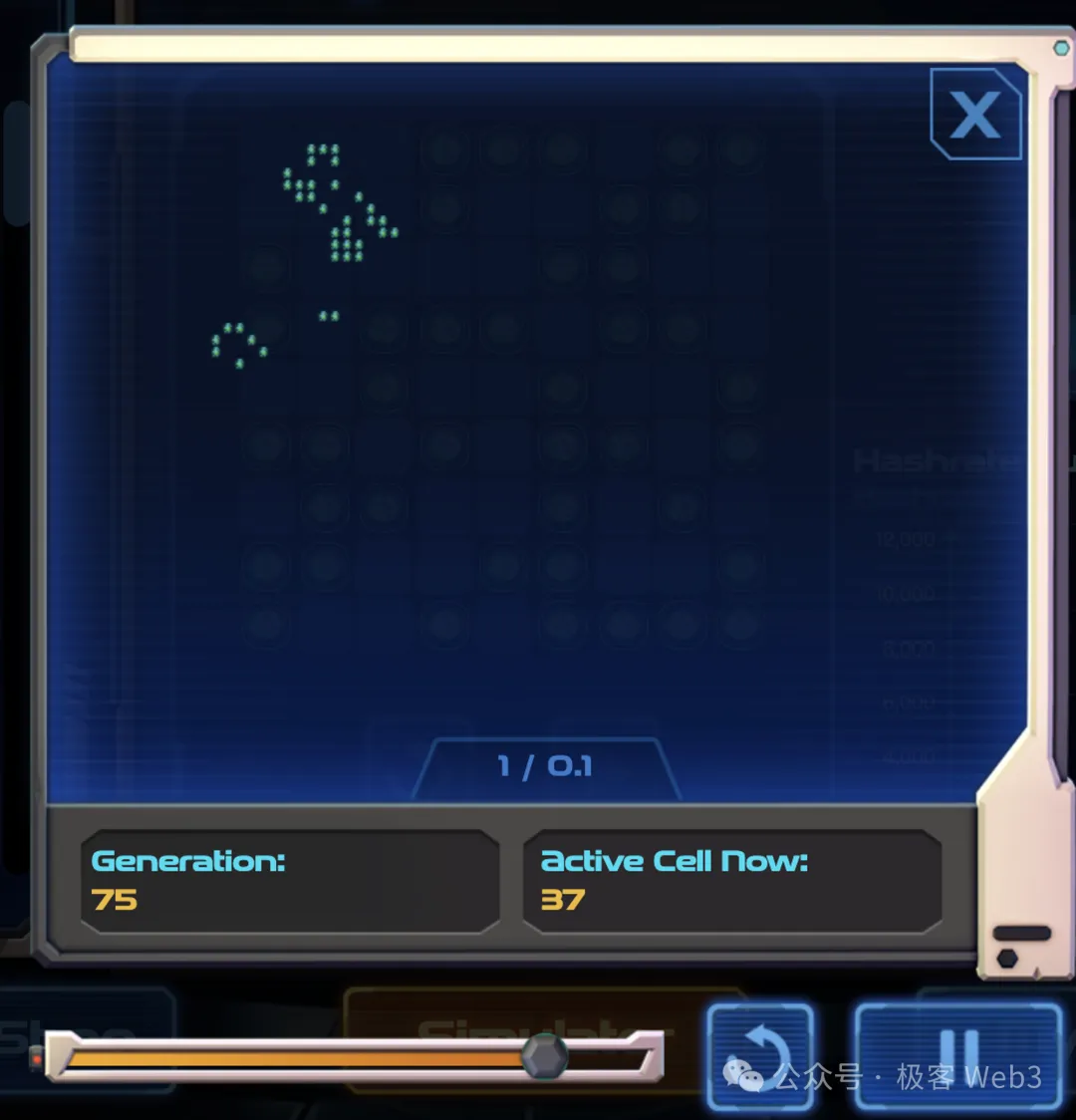

A BitLife’s cell states change as block height increases. Cellula allocates computing power based on a BitLife’s state at different block heights. At any given block height, the more living cells a BitLife contains, the higher its allocated computing power—creating a virtual mining rig.

Here’s a concrete example: Cellula participants must exhaustively test the 2^81 possible initial BitLife configurations off-chain, predicting post-evolution states to see if they meet reward criteria. Suppose current block height is 800, and the system announces: “At block 1000, the BitLife with the most surviving cells will receive the highest reward.” Participants now have a clear goal:

At block 800, I need to acquire a BitLife configuration that will have more surviving cells at block 1000 than any other BitLife.

This is the core gameplay of Cellula: your objective is to either build or buy the BitLife most likely to win mining rewards. This model allows ordinary or advanced retail users to develop their own mining rigs, sell self-built rigs to others, or purchase others’ rigs for mining. If building your own rig, you must simulate BitLife evolution states off-chain—a computationally intensive task. If buying someone else’s rig, you’re purchasing a BitLife with a predefined initial pattern, but you still need to evaluate its future state evolution, requiring off-chain computation. This is one of the most intriguing aspects of Cellula’s game design.

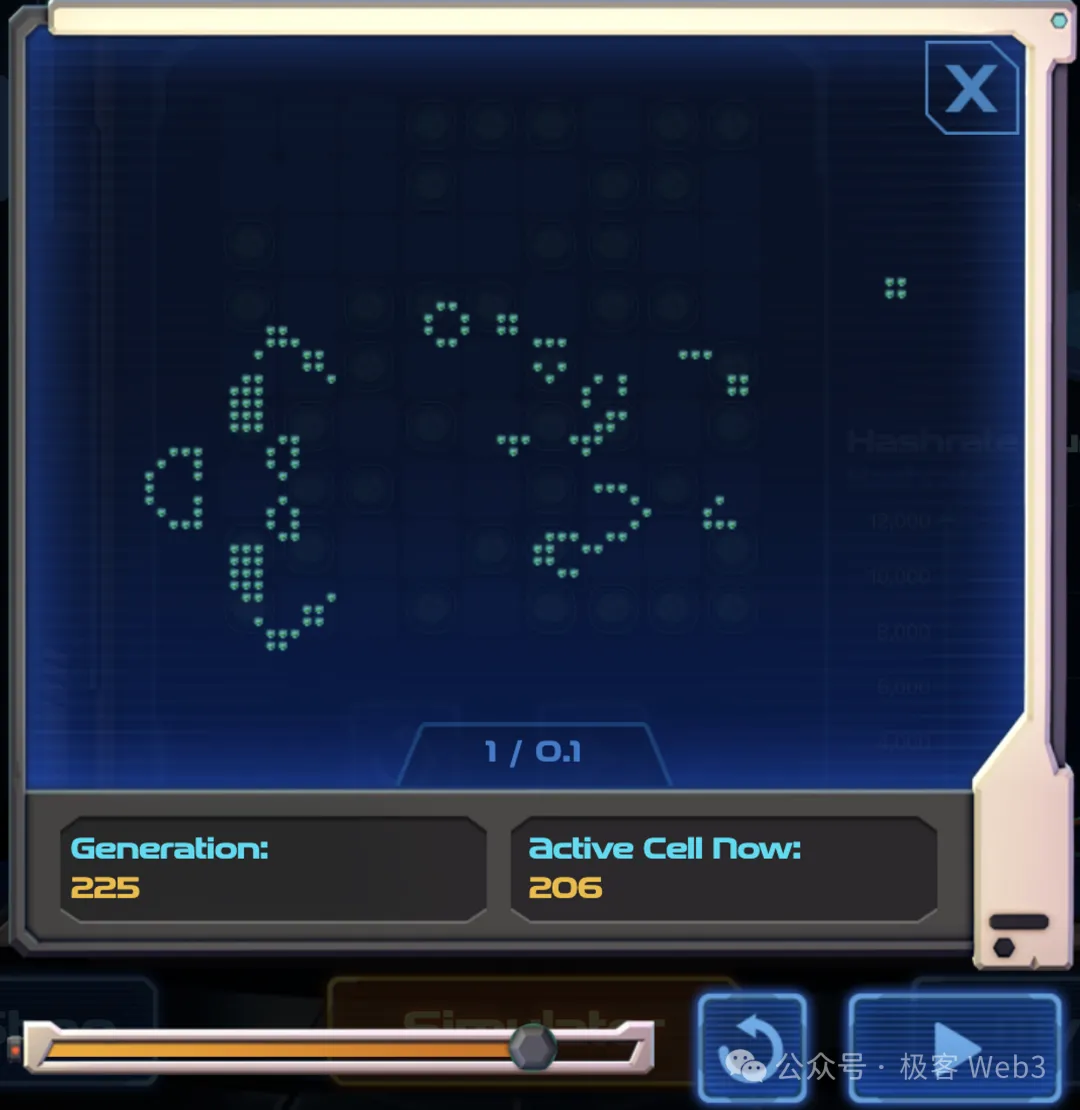

After understanding the core mechanics, consider additional details: living cells in a BitLife can overflow beyond the original 9×9 grid, meaning the number of live cells can greatly exceed 81, with no boundary limits. As shown in figures, if a BitLife’s active cells keep increasing, its allocated mining power rises accordingly. Conversely, poor initial configurations lead to dying cells and declining computing power.

The system distributes mining rewards (called “energy points” in-game) every five minutes, allocating them based on each BitLife’s share of total network computing power.

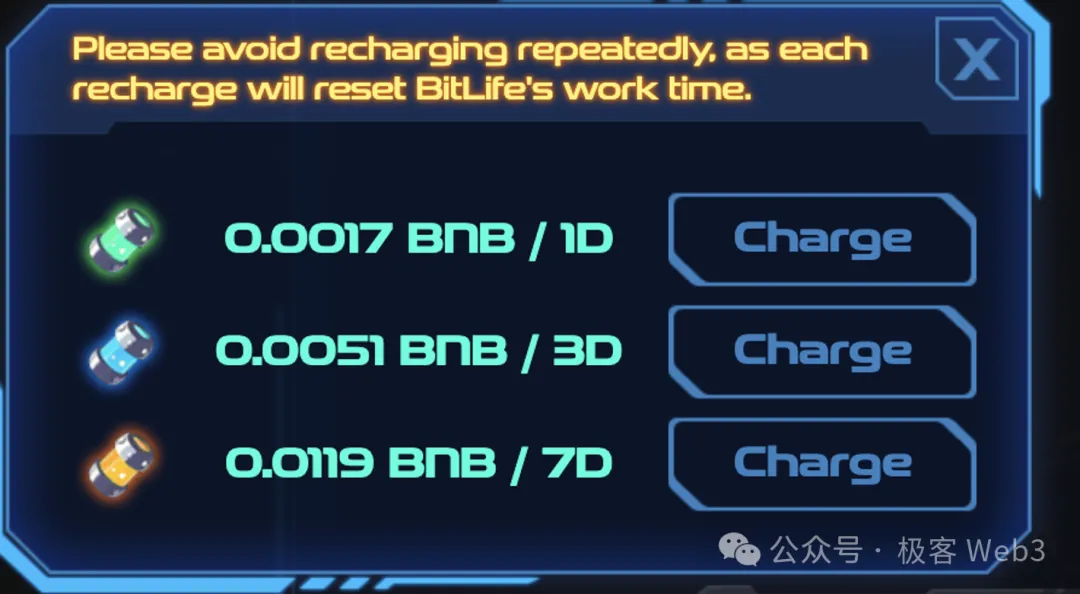

In Cellula, synthesizing a BitLife equates to “manufacturing” a new mining rig. Earlier we noted that a BitLife is represented as an NFT. Once minted on-chain, a BitLife must undergo a “charging” operation to activate mining. Charging lasts 1, 3, or 7 days, requires a small fee, and must be renewed upon expiration.

Notably, to encourage frequent charging, Cellula includes a “charging lottery” feature: each charge action gives a chance to win extra rewards (separate from regular mining rewards). We’ll briefly revisit this when discussing the Analysoor algorithm later.

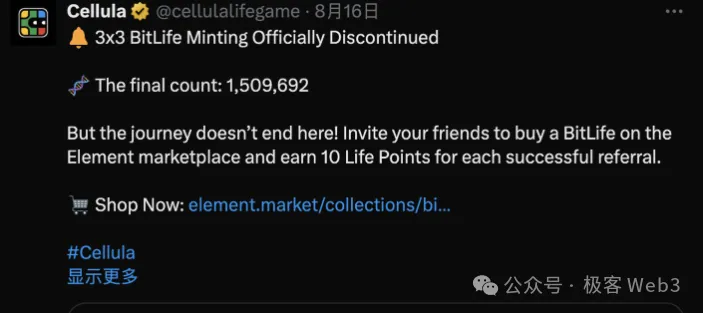

According to official Cellula rules, minting of 3×3 BitCell-containing BitLifes (i.e., 81-cell variants) has ceased. Players have collectively minted over 1.5 million such BitLifes. Future new users must purchase existing BitLifes on secondary markets and charge them to mine. Officially, this limited minting aims to stabilize the game ecosystem, preventing scientists from infinitely minting BitLife NFTs and devaluing mining rig worth.

Going forward, Cellula will introduce roles resembling mining rig manufacturers. These roles are permissioned—requiring token staking, public sales channels, and demonstrated community presence and influence. Manufacturers will mint and sell larger BitLifes containing 4×4 BitCells (16×9 = 144 cells). The number of BitLifes a manufacturer can produce will be capped by their staked token amount.

We’ve now broadly explained the core concepts of vPOW in accessible terms. vPOW is fundamentally a computational model based on defined rules, allowing participants to compete through strategic optimization, gamifying asset issuance and distribution. Cellula simulates the operation of BTC mining hardware markets by replacing the computational tasks within proof-of-work. Since mining power allocation dynamically adjusts, no single BitLife pattern is guaranteed globally optimal. Today’s top-performing BitLife may be surpassed tomorrow, generating complex emergent phenomena and dynamic strategies.

Analysoor Lottery Algorithm and VRGDAs Exponential Pricing Curve

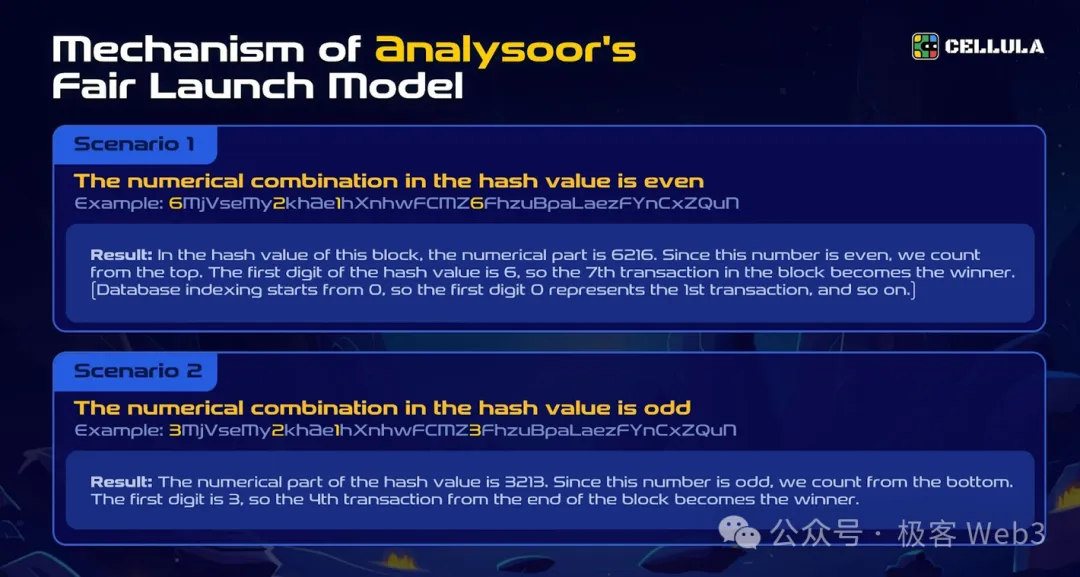

Previously, we focused on explaining Conway’s Game of Life and Cellula’s core mechanisms. Now let’s examine other elements in the game. Earlier, we mentioned Cellula’s charging lottery feature, which uses an algorithm called Analysoor to generate random numbers. Analysoor takes the block hash as input to a random number generator, selecting winners among those who charged in each block—introducing a lottery mechanism.

For example, in Analysoor’s design, suppose the current BNB Chain block hash is a long string like "6mjv....", containing digits 6, 2, 1, 6. Based on digit positions, the first digit is 6 and last is 6 (even), so counting proceeds forward. Extracted digits are zero-indexed; thus, digit 6 corresponds to position 7, making the 7th charging participant in that block the winner. Of course, actual designs can vary—this is just illustrative. Such randomized lottery algorithms effectively incentivize frequent charging and boost in-game ecosystem activity.

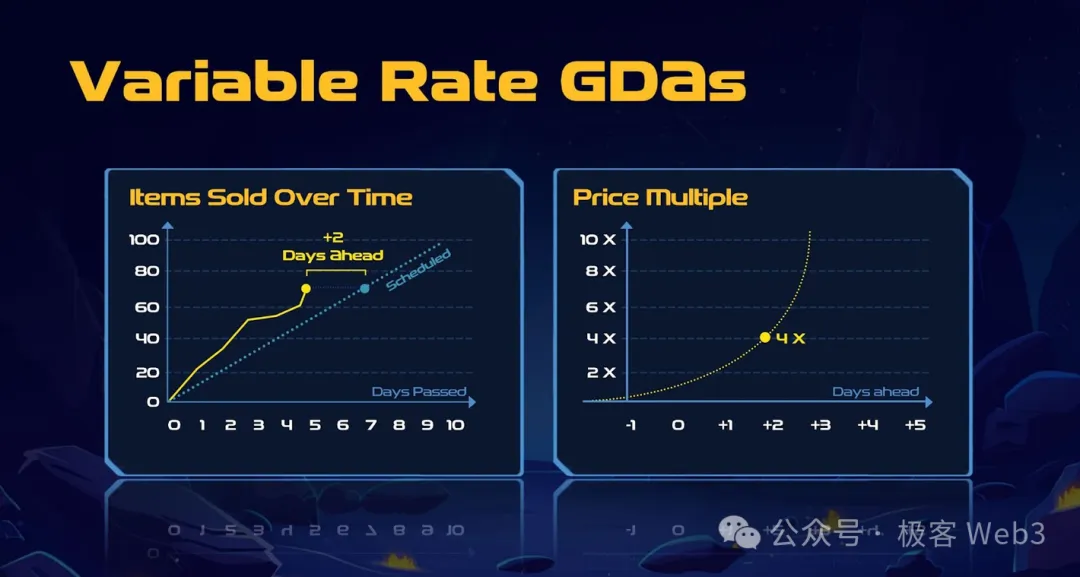

Additionally, within Cellula’s transaction model, there’s a challenge: once a powerful player mints a high-performance BitLife, its BitCell combination becomes public. Others can easily copy the same configuration, triggering mass cloning that undermines game randomness. To counter this, Cellula adopts Variable Rate Gradual Dutch Auctions (VRGDAs)—a pricing algorithm developed by Paradigm that dynamically adjusts prices: raising prices when mint volume exceeds expectations, lowering them when below target.

Suppose the initial plan is to mint 10 Type-A NFTs per day, starting at 1 CKB each. By day 5, 50 should be minted, but due to copying, 70 are created—matching the original day-7 target. To slow this down, exponential pricing rapidly increases mint cost to 4 CKB, suppressing further minting.

If by day 15 only 120 have been minted (target was 150), prices drop to stimulate minting activity.

In such scenarios, when a particular BitLife type is heavily minted in a short period, its mint price grows exponentially, effectively deterring scientists (anti-Sybil protection). It also provides market pricing for BitLifes/mining rigs: high-computing-power models command higher production costs, influencing secondary market prices and propagating throughout the supply chain.

Conclusion: Viewing Cellula Through the Lens of Player Strategy and Game Theory

After covering all core designs of Cellula, let’s analyze this imaginative game mechanism from a strategic player perspective. In vPOW, multiple participant types employ different strategies. In the primary issuance market, a “scientist” might write code combining various BitCells to discover high-computing-power BitLifes, aiming for higher mining returns. Meanwhile, MEV players monitor on-chain mint events and quickly replicate successful BitLife types once spotted.

However, thanks to VRGDA’s exponential pricing algorithm, the mint price of any single BitLife type can skyrocket, effectively curbing scientists (anti-Sybil). It also establishes pricing for BitLifes/rigs: higher computing power leads to higher minting/production costs, which inform secondary market valuations and ripple through the entire supply chain.

Paralleling BTC mining rig distribution: when a scientist discovers a high-power BitLife, it's like a chipmaker unveiling new hardware; MEV players replicating it resemble first-tier distributors setting initial prices; subsequent secondary market trades mirror retail users buying equipment from dealers.

The difference is that discovering new BitLifes happens much faster than real-world mining rig R&D, and anyone can participate in simulating BitLife evolutions—greatly democratizing access to “mining rig development.” "Everyone can become a scientist," a scenario far friendlier to most users and impossible in real-world mining hardware production chains.

For the project team itself, adopting a POW-style distribution inherently reduces their control. Therefore, neither scientists, project teams, nor regular players can unilaterally dominate the market. Strategic interactions among these three parties during minting and issuance stages create a balanced competitive landscape—no single entity can monopolize the ecosystem, fostering dynamic equilibrium.

Overall, compared to BTC’s mining rig supply chain, Cellula’s model represents a more engaging social experiment.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News