Once you understand trustless economics, you understand Ethereum.

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Once you understand trustless economics, you understand Ethereum.

The introduction of smart contracts provides society with a new infrastructure that supports the development of next-generation applications and services with minimal trust requirements.

Author: Naly

Translation: TechFlow

The Trustless Economy – Understanding Ethereum

Human society fundamentally operates on trust. From personal relationships to the global economic system, trust is the thread that binds us together.

The key question is: how strong is this thread?

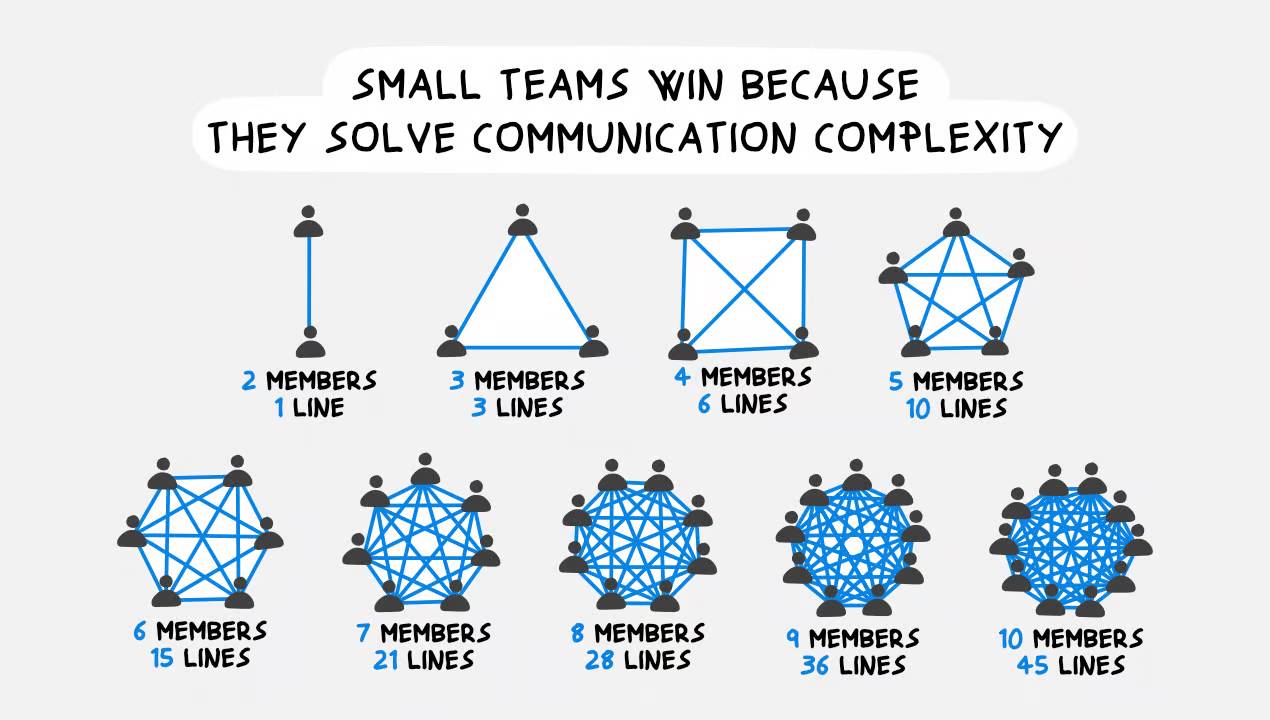

In small-scale environments, trust can be very robust. This is because trust is based on relationships, knowledge, and direct accountability—where a person’s reputation directly impacts the relationships they build.

However, as interactions increase in number and scale, the relative strength of trust becomes fragile. Why? The larger the crowd, the fewer interpersonal connections are formed, reputational influence diminishes, incentives must be stronger, and systems must function more efficiently.

Table of Contents

-

The Trustless Economy – Understanding Ethereum

-

Stories of Trust

-

The Great Game

-

-

The Birth of Ethereum

-

Power in Numbers

-

Trustless Code

-

Bitcoin vs. Ethereum

-

The World Computer

-

Economic Security

-

Programmable Economy

-

Decentralized Applications

-

Decentralized Finance

-

Decentralized Stablecoins

-

Lending Markets

-

Decentralized Exchanges

-

Liquid Staking Protocols

-

-

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations

-

Trustless Economy

-

Case Study

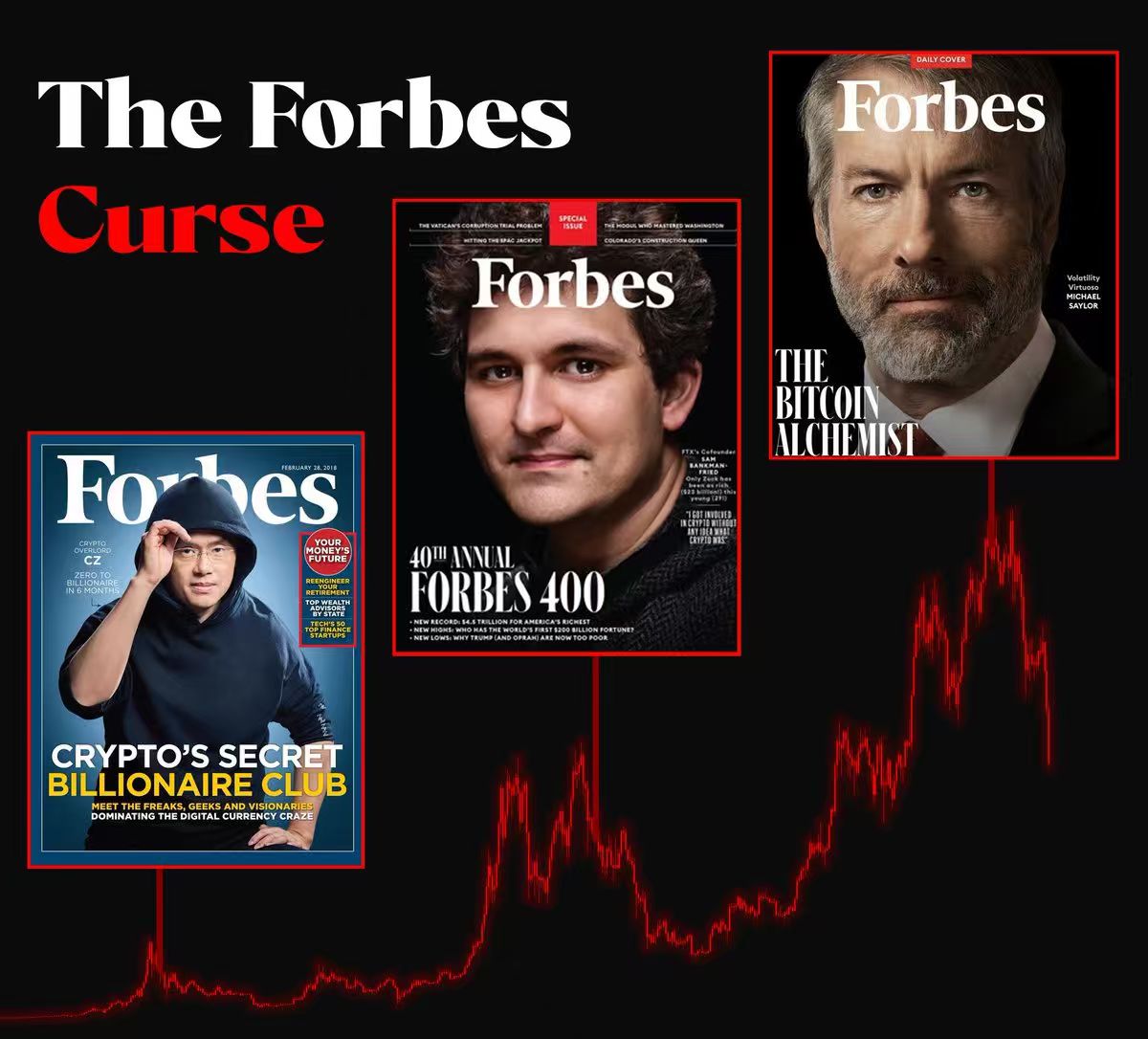

In his book "Sapiens," Yuval Noah Harari explains that trust can be maintained in groups of up to around 150 people—a number known as Dunbar's number. When group size exceeds this threshold, humans rely on shared myths, religions, and ideologies.

In today’s world, as relationships scale into large organizations, corporations, or global markets, society’s solution has been to institutionalize trust. In effect, we weave a narrative that makes certain individuals within the system “trustworthy” by reputation.

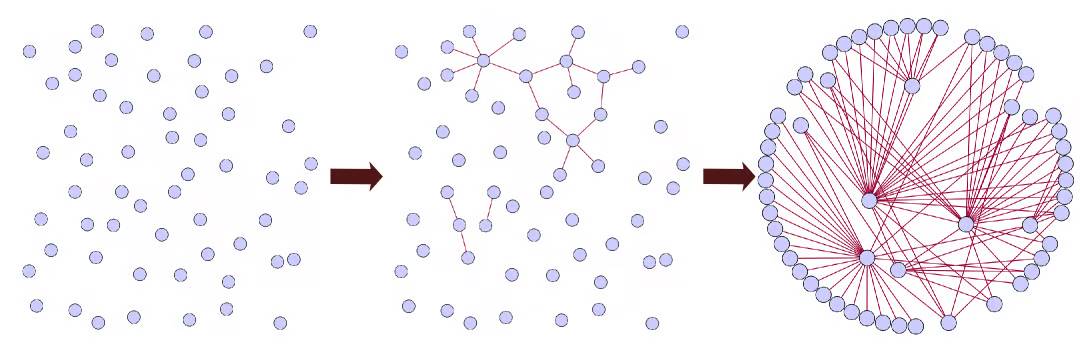

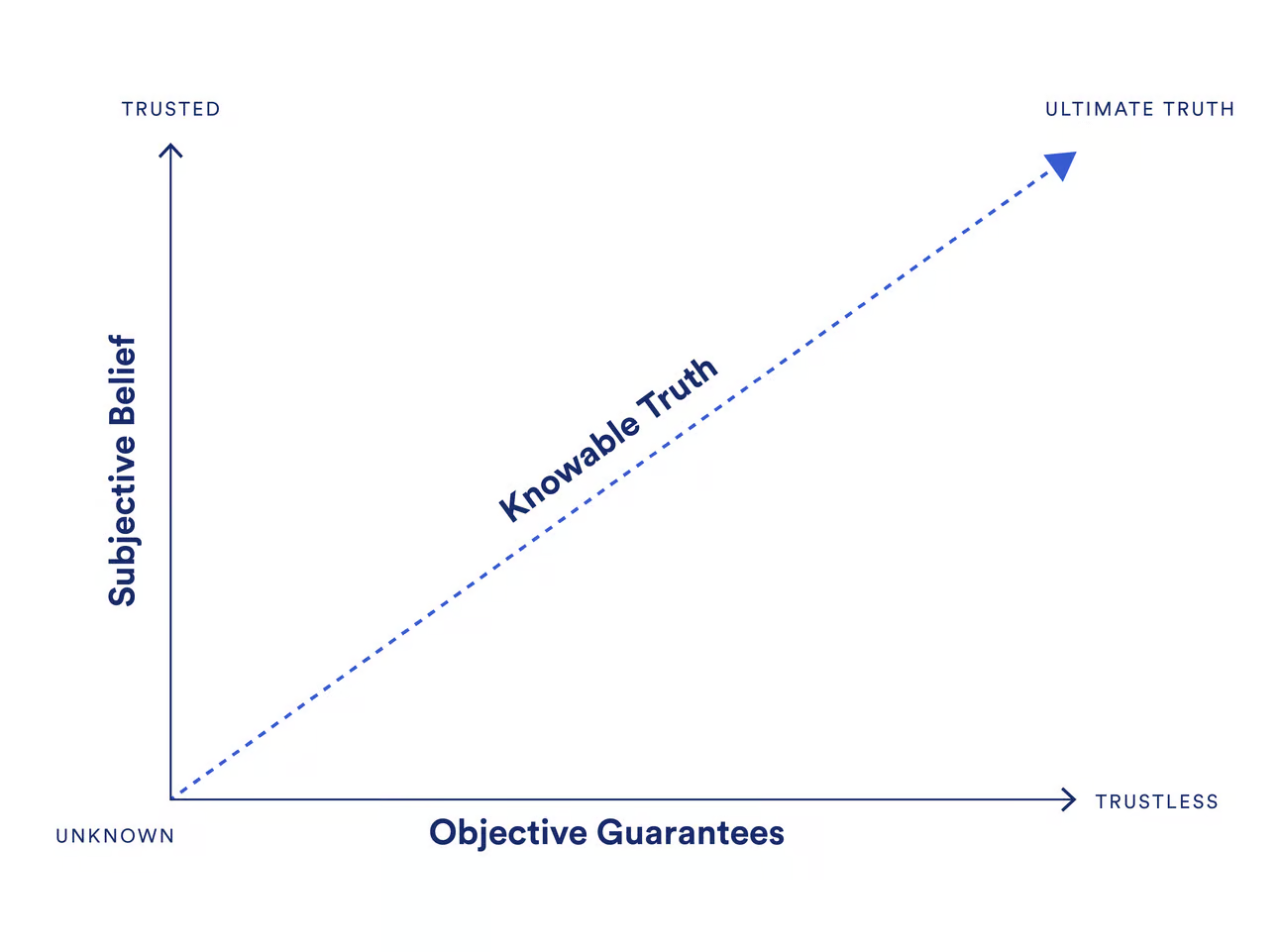

The diagram below illustrates this concept visually.

Although it sounds simple, this doesn’t always work.

During the 2008 financial crisis, financial products deemed extremely safe (AAA-rated) by these “trusted” banks and credit rating agencies turned out to be exactly the opposite. Banks wrapped poor-quality assets in fancy packaging and sold them as premium goods. Once people realized this, the system collapsed—catastrophically.

Stock markets crashed, wiping out approximately $30 trillion in global market value. U.S. housing prices fell by 30%, and over 3 million homes were foreclosed.

To grasp the scale of $30 trillion, consider this: if you stacked $1 bills, the pile would reach about 2 million miles high—more than eight times the distance from Earth to the Moon. Or, if you spent one million dollars per day, it would take over 82,000 years to spend it all!

The 2008 financial crisis was just one of many examples where catastrophic failures of trust led to systemic collapse.

-

Enron Scandal (2001): Enron’s fraudulent accounting practices led to its bankruptcy, eroding trust in corporate governance and auditing standards.

-

Wells Fargo Account Fraud Scandal (2016): Wells Fargo employees created millions of unauthorized bank and credit card accounts, resulting in significant financial losses and loss of public trust.

-

Facebook-Cambridge Analytica Data Scandal (2018): Cambridge Analytica collected personal data from Facebook users without consent, highlighting the risks of centralized control over personal data.

-

Equifax Data Breach (2017): A major data breach at Equifax exposed sensitive information of 147 million people, undermining trust in centralized credit reporting agencies.

The Great Game

Why do these trusted entities continually fail our trust?

Is it due to inherent human greed, or is there a mathematical reason? It turns out, both.

Life is a great game. You roll the dice, move forward on the board, buy houses, collect $200 when passing Go, upgrade skills, form alliances, make enemies, and ultimately build and break trust. It’s an endless cycle.

To quantitatively analyze major life decisions, we can turn to game theory—the mathematical study of strategic interaction.

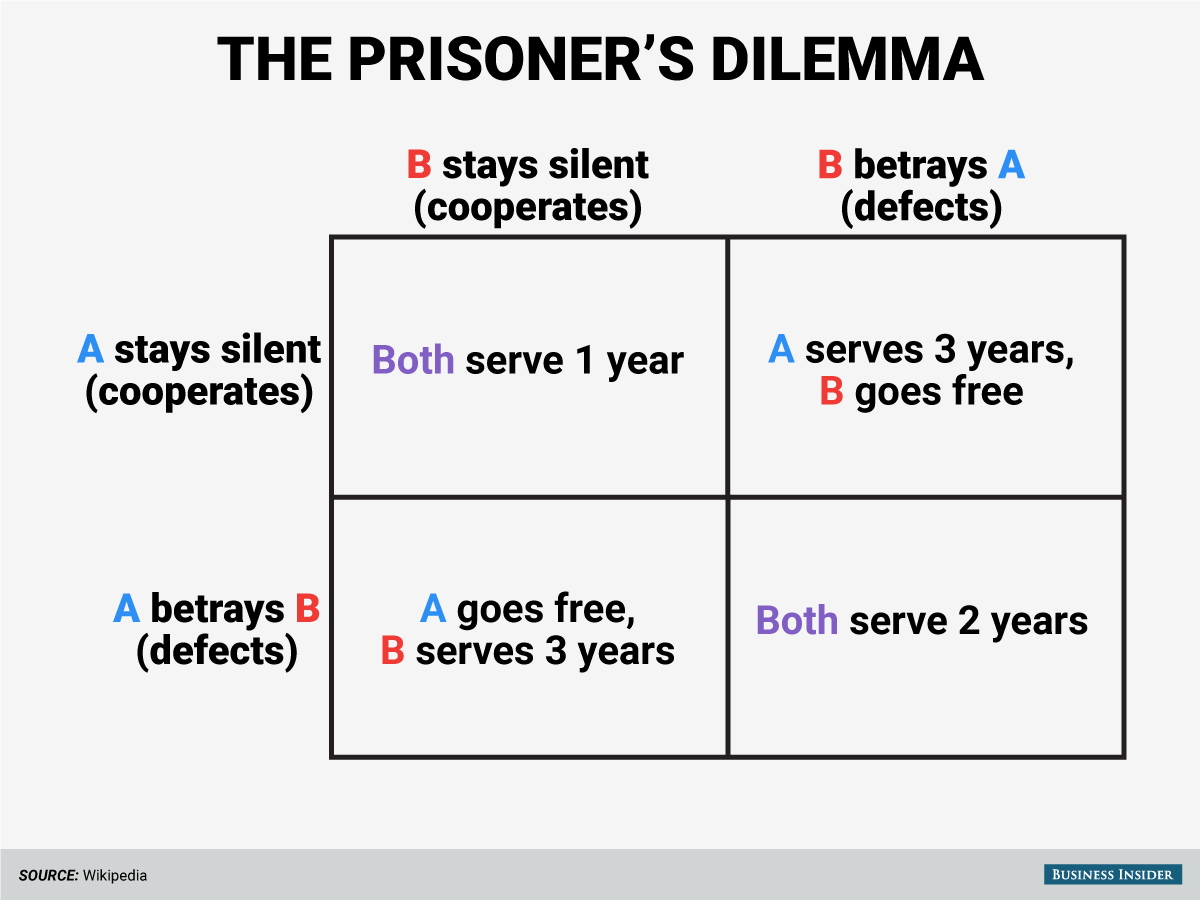

A common entry point into this field is the "Prisoner’s Dilemma"—a scenario where two people are arrested and held separately. They can choose to cooperate by staying silent or betray each other.

If both remain silent, they serve short sentences. If one betrays while the other stays silent, the betrayer goes free while the silent one gets a longer sentence. If both betray each other, they receive moderate sentences.

This dilemma highlights the conflict between individual rationality and collective rationality, showing how pursuing self-interest can lead to worse outcomes for society as a whole.

If we map this mechanism across multiple iterations and calculate success probabilities (cumulative scores), you might expect a society of traitors to thrive; after all, the old saying goes—nice guys finish last.

In fact, the results are quite different. When this game is programmed into computers and run thousands of times with cumulative scoring, some fascinating insights emerge.

The most successful computer program was called "Tit-for-Tat," with the following characteristics:

-

Kindness: Never be the first to defect

-

Retaliation: Immediately respond if the opponent defects

-

Forgiveness: Retaliate but don’t hold grudges

(For more on game theory, see this video.)

So, is being kind and trustworthy beneficial for society?

Well, it makes sense—cooperation tends to be more advantageous in almost every life situation. This is evident in team sports, relationships, and business. Those who cooperate well often become the best!

What I find particularly interesting is that when mapped over longer time spans and applied to areas like biological evolution, another pattern emerges.

(For evolutionary game theory, see this video.)

As cooperative societies grow, they reach an unstable point because any individual inclined to betray immediately disrupts balance and weakens interpersonal ties (see above, Dunbar’s number). This is clearly seen in the rise of empires or corporations—once internal betrayal and imbalance begin, decline becomes inevitable.

In short, in a team of good people, only one bad actor is needed to exploit the system.

Evolutionary selection favors strategies that decide whether to help based on the recipient’s prior reputation. This works in small groups, but as populations exceed our previously discussed limit of 150, reputation-based trust relying on central authorities becomes vulnerable.

To enable widespread and advanced cooperative societies, a supporting structure is required. Like many others, I believe the global financial system and the livelihoods of every member of society cannot depend solely on the “good word” of those economically incentivized to manipulate truth for profit.

Financial trust urgently needs redefinition.

The Creation of Ethereum

Power in Numbers

In 2009, Bitcoin was born—an economic model designed to eliminate trust issues in finance through an immutable digital asset.

Bitcoin achieved this by introducing blockchain—a decentralized database secured by a vast network of computers and driven by a finite monetary unit: Bitcoin (BTC).

Bitcoin is a peer-to-peer, cryptographically secure network. It allows users to self-custody their funds, governed by a fixed issuance schedule that no single authority can arbitrarily inflate. These factors have earned Bitcoin the nickname “digital gold.”

See this article for an overview of the Bitcoin network.

Figure: Permissionless Economy – Bitcoin

Trustless Code

Six years after Bitcoin’s creation, Vitalik Buterin envisioned a more generalized blockchain—one that not only allows users to hold and transfer digital assets but also leverages blockchain immutability to create trustless applications and build decentralized sub-economies.

These statements may seem confusing at first—please bear with me.

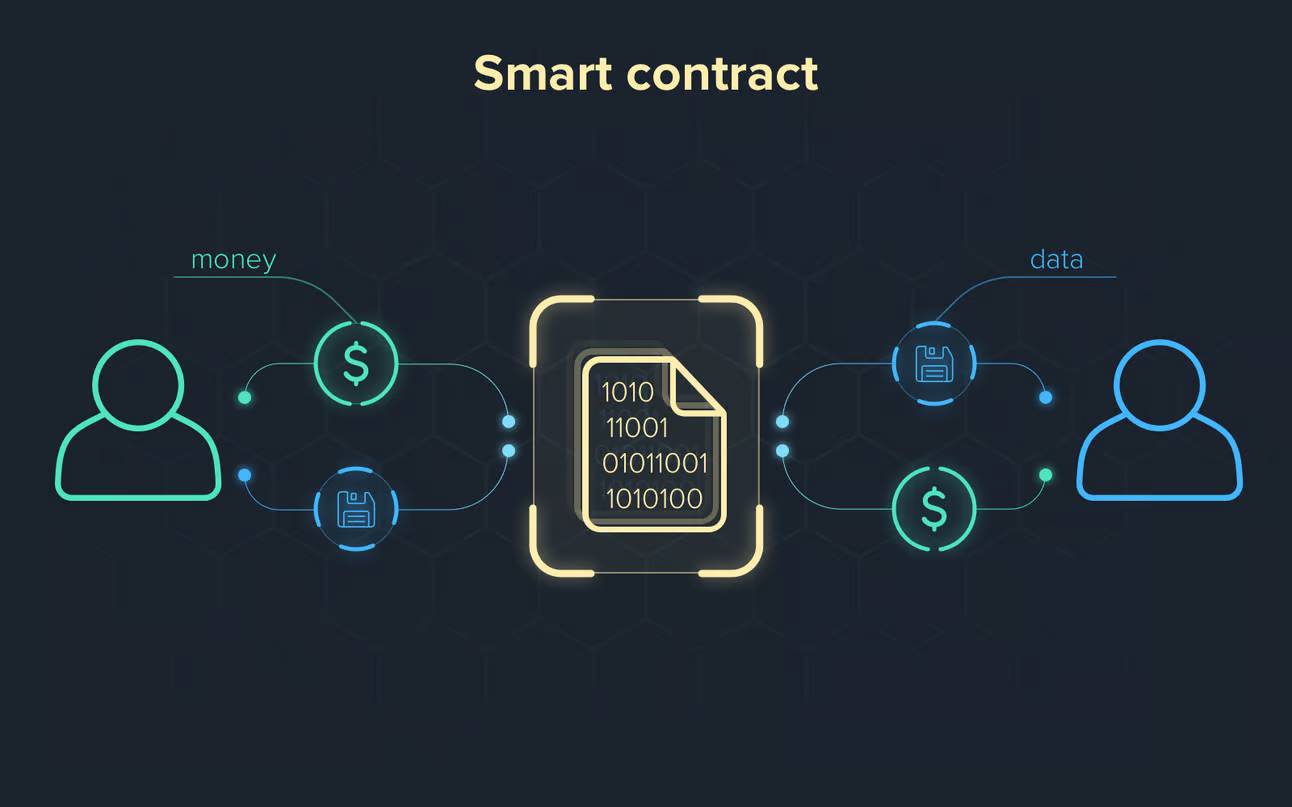

The key takeaway is that Ethereum’s core innovation is smart contracts.

Smart contracts are digital protocols that automatically execute and enforce agreements under predefined conditions via code—without human intervention.

Their implementation relies on several key blockchain features:

-

Immutable Ledger: Once deployed, contract terms cannot be altered.

-

Decentralized Economic Security: The network is secured through economic incentives and a large number of participants—not a single central entity.

Think of a smart contract as a cookbook that automatically prepares a meal once all ingredients are ready. Once the code (in this analogy, the recipe) is provided, no further human input is needed.

This recipe is open-source, meaning anyone can inspect what will be made (and how) before agreeing to the contract. It is also immutable—once deployed, it cannot be changed.

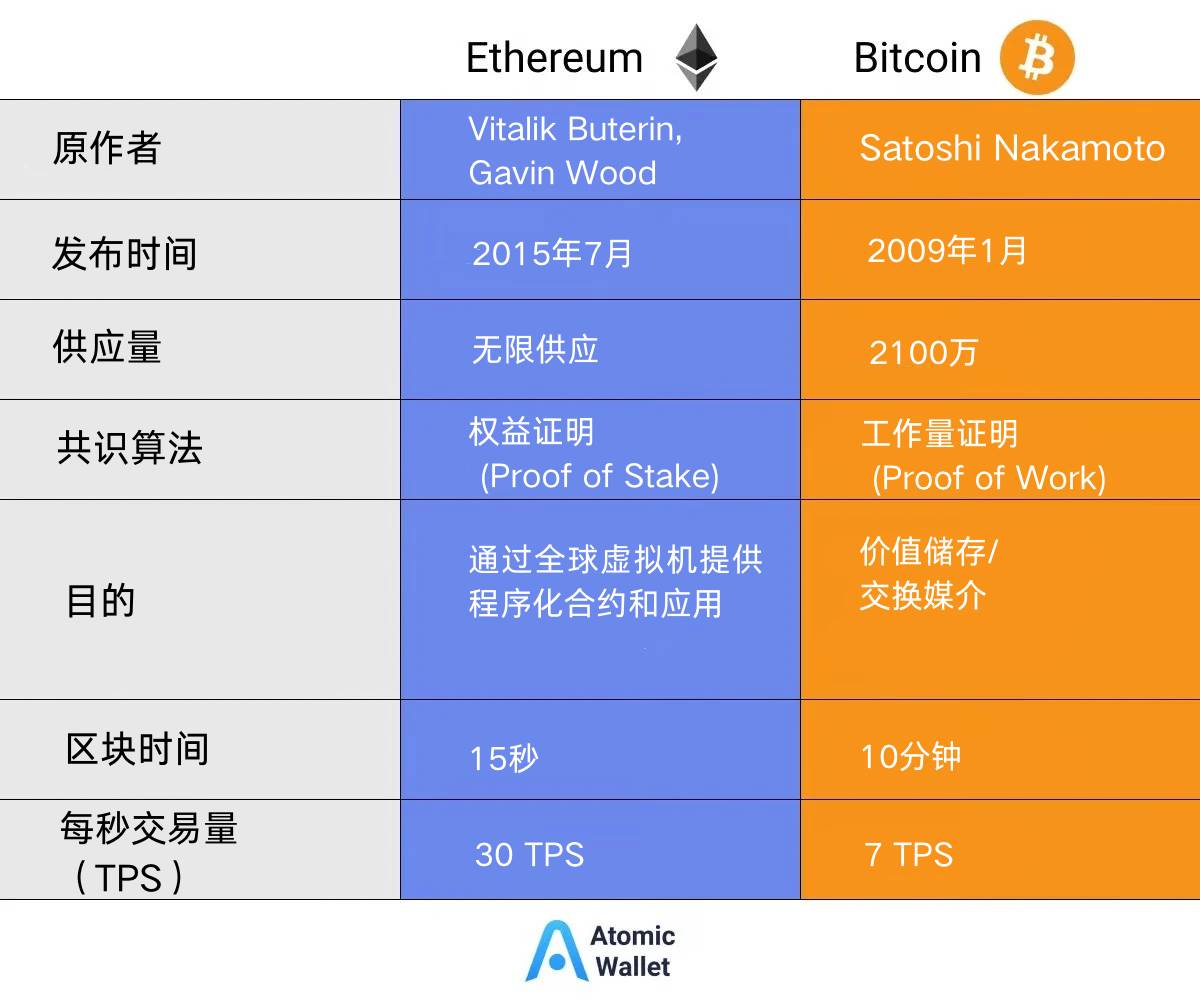

Bitcoin vs. Ethereum

At a macro level, comparing Bitcoin and Ethereum is like comparing Bitcoin to a highly secure calculator. Just as a calculator performs arithmetic operations, the Bitcoin network efficiently handles peer-to-peer value transfers.

Ethereum, on the other hand, is more like the Apple App Store—it provides developers with a foundational platform to build and run applications.

Just as the App Store offers a secure environment for iPhone apps, Ethereum provides a decentralized, programmable blockchain environment for creating and executing smart contracts and decentralized applications (dApps).

Extending this analogy, while Bitcoin is a transaction network, Ethereum is like an entire computer.

The World Computer

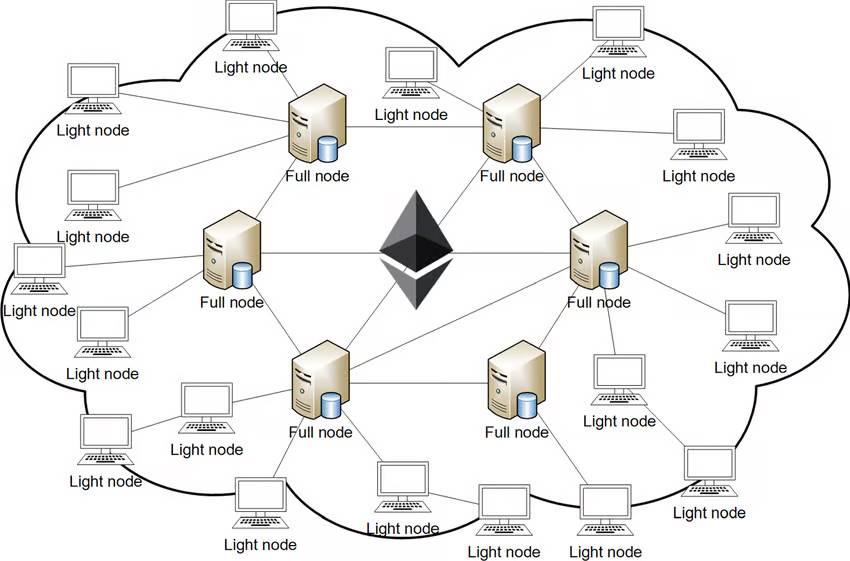

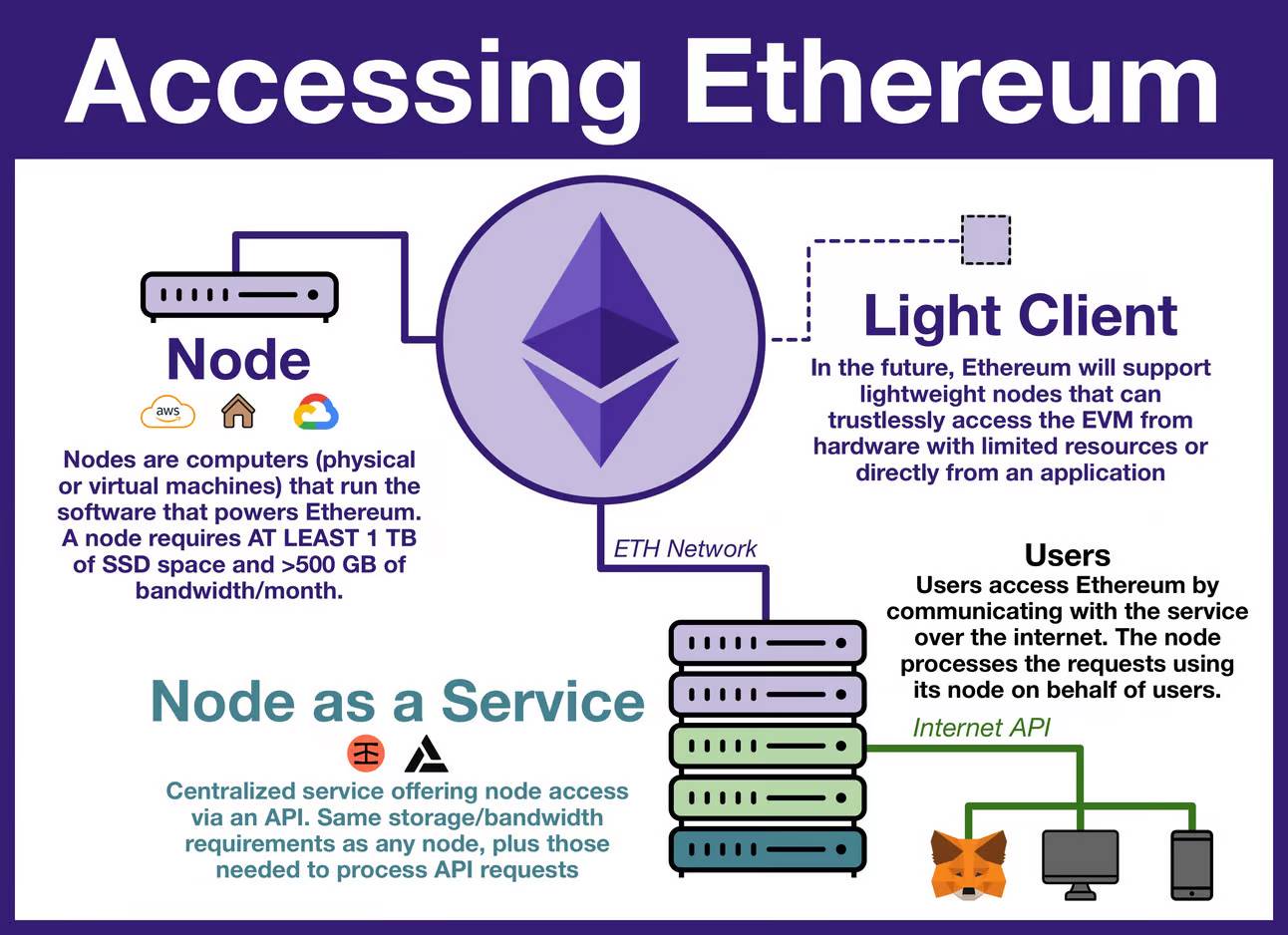

Unlike traditional computers, whose state is internally implemented (i.e., the specific condition of the system or software at a given moment), the Ethereum computer—also known as the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM)—runs by executing contracts across a vast network of computers.

When a transaction is executed on the Ethereum blockchain, the EVM ensures that every computer (or node) in the network processes and validates the transaction identically.

Each time a new set of transactions is added, it’s called a “block”—hence the term blockchain. Public blockchains like Ethereum allow anyone to add data—but never delete it.

The network is powered by the cryptocurrency Ether (ETH), which pays for computational resources. Every transaction requires ETH to execute, meaning that if Bitcoin (BTC) is digital gold, then Ether (ETH) is digital oil.

In a recent report, ICBC—the world’s largest bank—praised the growth of Ethereum and Bitcoin. The bank likened Bitcoin to gold due to its scarcity, while calling Ethereum “digital oil,” noting its role in “providing a powerful platform” to support numerous Web3 innovations.—FXStreet

It’s important to note that when we refer to transactions, unlike on the Bitcoin network, we’re not just talking about sending funds. On Ethereum, a transaction refers to any operation that changes the network state—which, thanks to smart contracts, could be anything from deploying a new contract, voting on governance, to buying an item in a blockchain game. (More on this later.)

Economic Security

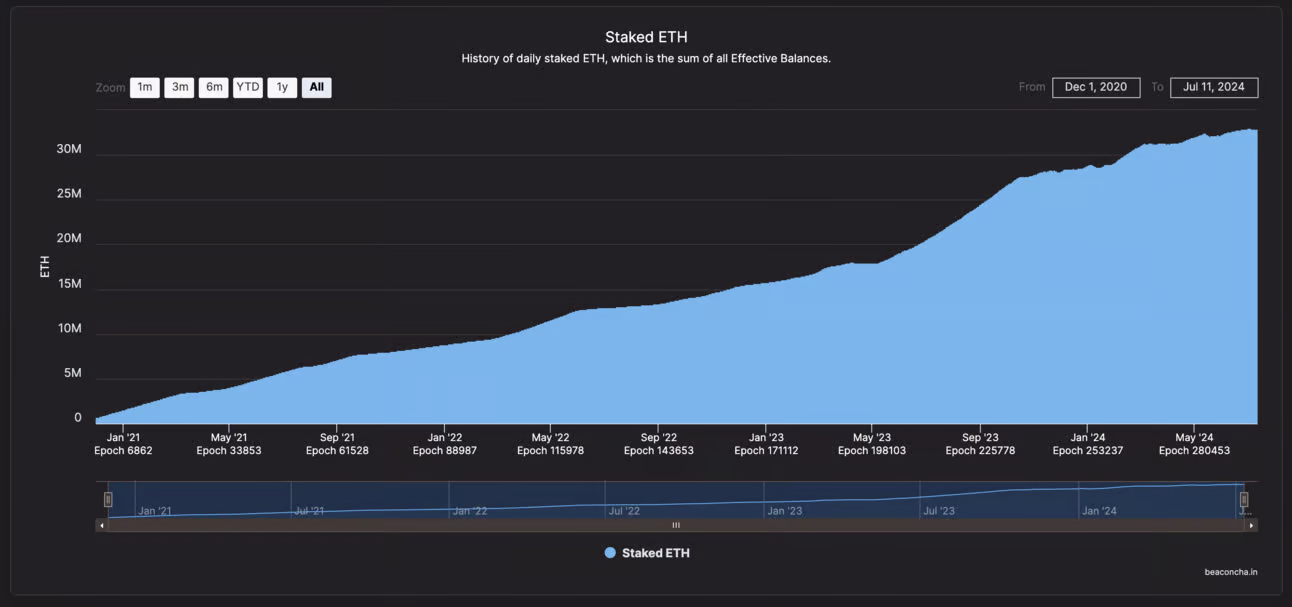

Figure: Over 30 million ETH staked on the Ethereum network

One of the first questions people ask about the Ethereum network is security. How do we ensure these smart contracts are secure?

Ethereum is economically secured through the Proof-of-Stake (PoS) consensus mechanism.

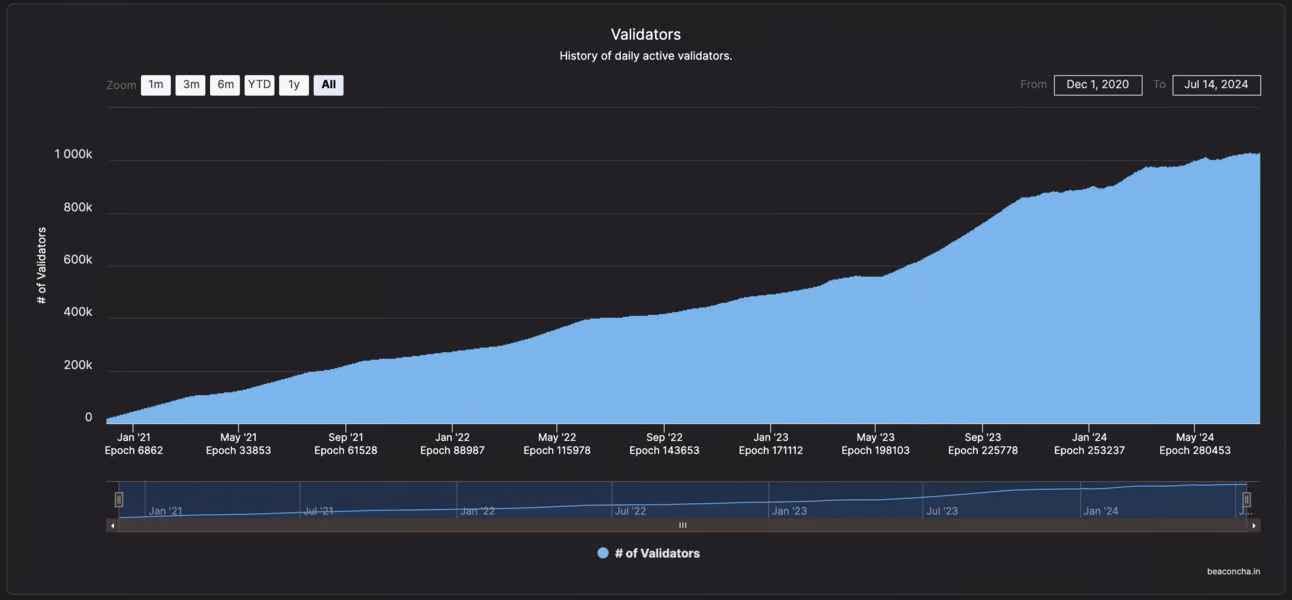

In PoS, network state changes are managed by validators—participants responsible for storing data, processing transactions, and adding new blocks to the blockchain.

To become a validator, users must lock up Ether (ETH) as collateral and run the necessary computing hardware to maintain and update the network state. To illustrate how new blocks are added, suppose two simple transactions occur within a block:

-

John sends 1 ETH to Betty.

-

Developer Bob spends 2 ETH to create a new smart contract.

The job of all validators in the network is to verify these two transactions and update the network state accordingly. In this example, validators need to confirm that John’s account is debited 1 ETH, Betty’s account is credited 1 ETH, and a new smart contract is created and recorded on the blockchain.

Validators update the state locally on their hardware. Once a majority (over 50%) agree the transactions are valid and state changes are correct, the next block is added. This consensus mechanism ensures integrity and accuracy of the network state.

If a validator acts dishonestly and misreports the network state (e.g., updating their local machine to show John sent 1 ETH to George instead of Betty), and over 50% of the network disagrees, they risk being slashed—losing part or all of their staked ETH.

Figure: Over 1 million validators on the Ethereum network

Validators are rewarded with newly minted ETH and transaction fees, providing economic incentives to act in the network’s best interest.

In short, participants are economically incentivized to secure the Ethereum network.

This 50% rule means that to tamper with information or cheat the system, someone would need to control over half (51%) of the network’s computers. Currently, this would cost approximately $103 billion.

This is nearly impossible due to the following reasons:

-

Market Liquidity: The Ethereum market lacks sufficient liquidity to handle a $103 billion purchase without extreme price volatility.

-

Exchange Limitations: No single exchange—or combination of exchanges—can process such a massive purchase in one transaction.

-

Regulatory and Compliance Issues: A purchase of this scale would attract regulatory scrutiny and require compliance with extensive anti-money laundering (AML) and know-your-customer (KYC) regulations.

-

Counterparty Risk: Finding enough sellers to meet a $103 billion demand for ETH is nearly impossible.

Programmable Economy

We’ve learned that Ethereum isn’t just about transactions and storing financial value—it enables the creation and execution of trustless agreements based on predefined instructions.

This means that while Bitcoin created a limited decentralized currency unit, Ethereum opens the door to entirely new financial systems.

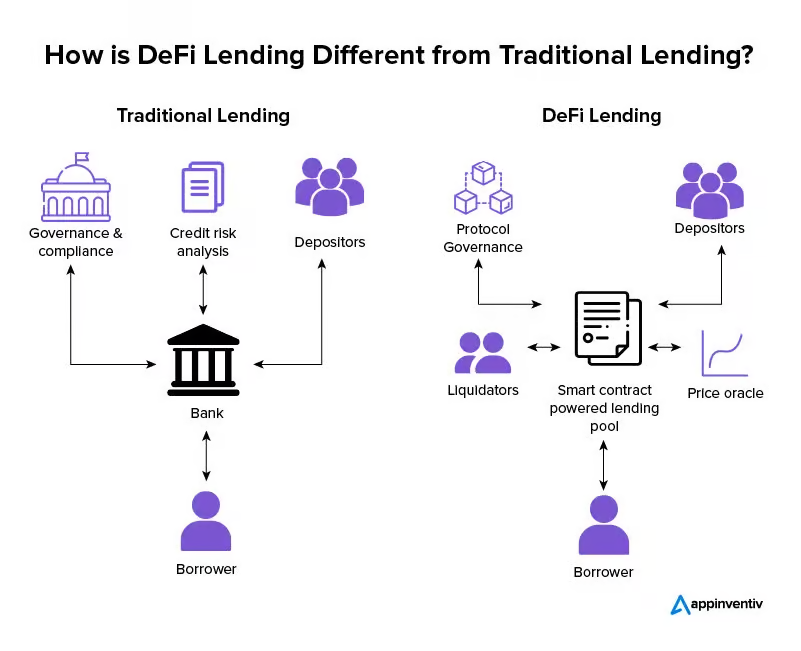

Previously, financial systems relied on intermediaries like banks and lending agents. Smart contracts now allow programming of decentralized applications (dApps) that require no human intervention once deployed.

Decentralized Applications

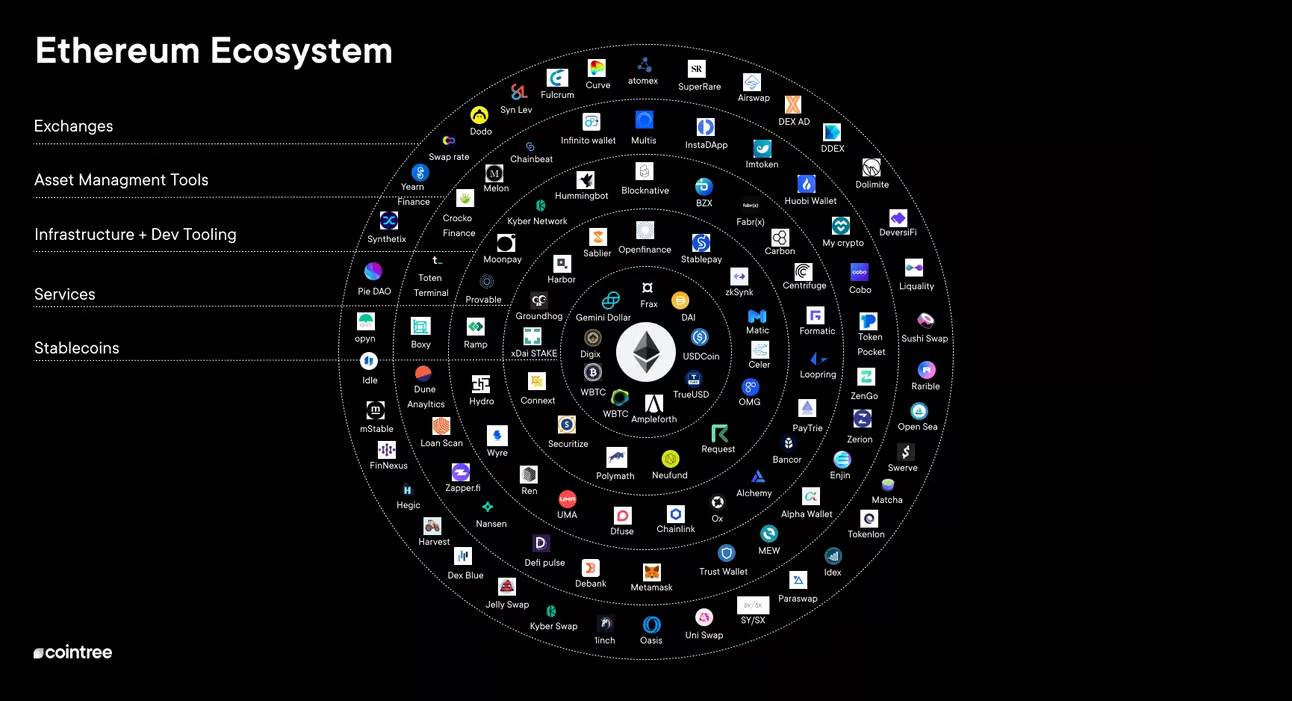

So, what kinds of decentralized applications can be built?

Almost anything that involves protocols, intermediaries, trust, and centralized points of failure can leverage blockchain technology to decentralize and reduce systemic pressure.

From supply chain management and healthcare to gaming and digital identity, the design space is virtually limitless. Beyond eliminating human intermediaries, blockchain technology also enhances data efficiency and connectivity. Isolated and outdated databases are evolving toward more efficient and interconnected technological layers.

-

Blockchain, the digital record-keeping technology behind Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, is a potential disruptor in finance. But it also holds great promise in supply chain management. Blockchain can significantly improve supply chains by accelerating and lowering the cost of product delivery, enhancing product traceability, improving coordination among partners, and helping access financing.—Harvard Business Review

So far, the area gaining the most traction is Decentralized Finance, or DeFi.

Decentralized Finance

On-chain lending markets allow anyone with internet access to provide tokenized assets and earn interest by lending them out. These transactions involve no intermediaries—the interest rate is predetermined by a mathematical model of supply and demand encoded in cryptographic code.

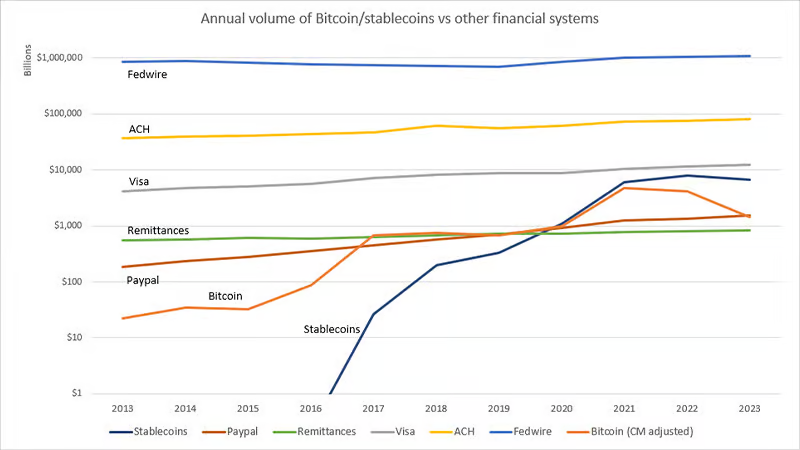

The emergence of stablecoins has provided users with tokenized versions of national currencies (like USD and EUR)—a $161 billion industry already adopted by traditional financial giants such as Visa and PayPal.

Figure: Visa

Stablecoins are backed by transparent off-chain reserves (such as U.S. Treasuries) or pegged to the dollar but collateralized by ETH, enabling instant access to chosen tokenized currencies online for anyone, anywhere.

This technology is especially critical in countries where centralized power has led to currency inflation and devaluation due to greed and manipulation.

For example:

-

Venezuela: Due to hyperinflation, many Venezuelans have turned to stablecoins like Tether (USDT) to store value and conduct transactions, bypassing the unstable bolívar.

-

Argentina: Facing high inflation and currency controls, Argentinians increasingly use stablecoins to protect savings and facilitate international trade.

-

Turkey: Amid economic uncertainty and currency depreciation, Turkish citizens adopt stablecoins to shield wealth from lira volatility.

In essence, stablecoins give fiat currencies superpowers of the internet, allowing them to flow like any other internet data.—Circle

Let’s dive deeper into some of the most prominent Decentralized Finance (DeFi) protocols.

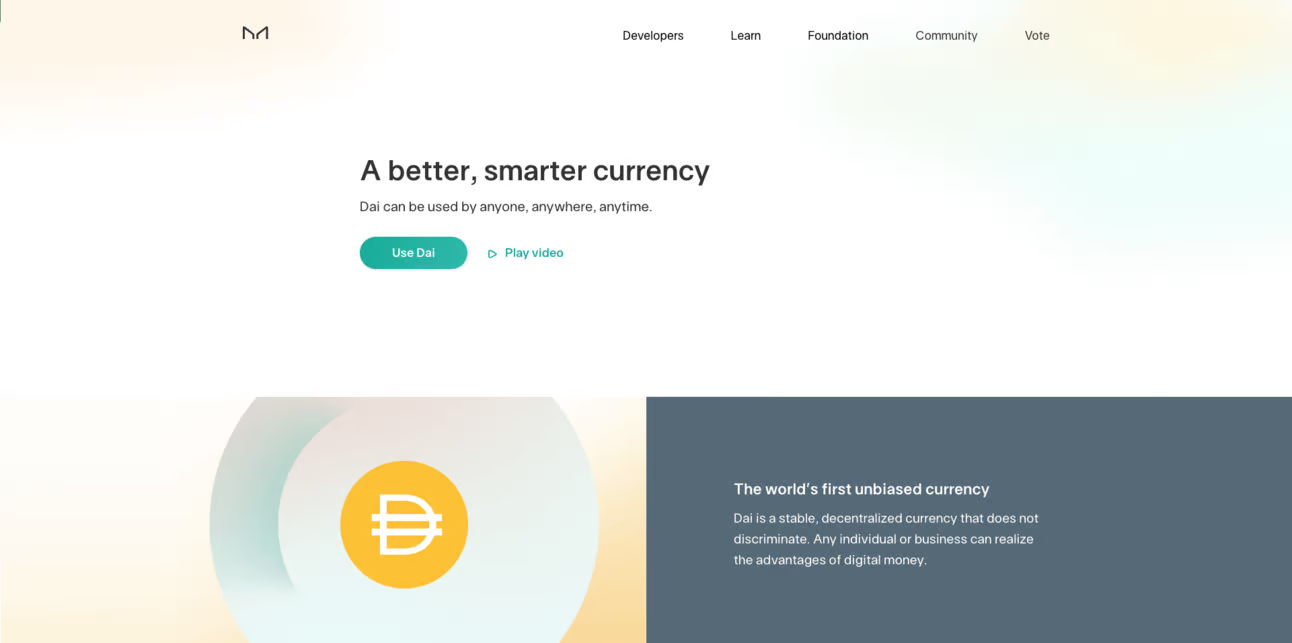

Decentralized Stablecoins

The first decentralized application (dApp) built on Ethereum was Maker DAO, a protocol allowing users to create and manage a decentralized stablecoin called Dai. Dai is pegged to the U.S. dollar but backed by ETH.

To obtain Dai, users must deposit Ether (ETH) as collateral in a smart contract. Once generated, purchased, or received, Dai can be used like any other cryptocurrency—sent to others, used to pay for goods and services, or even held to earn interest via the Dai Savings Rate (DSR) feature within the Maker protocol.

Lending Markets

Aave is a decentralized, non-custodial lending protocol where users can participate as depositors or borrowers. Depositors provide liquidity to earn passive income, while borrowers can access these assets for use in other DeFi applications.

Users can deposit their chosen assets and amount, earning passive income based on market demand. After depositing, users can borrow against these assets as collateral.

Decentralized Exchanges

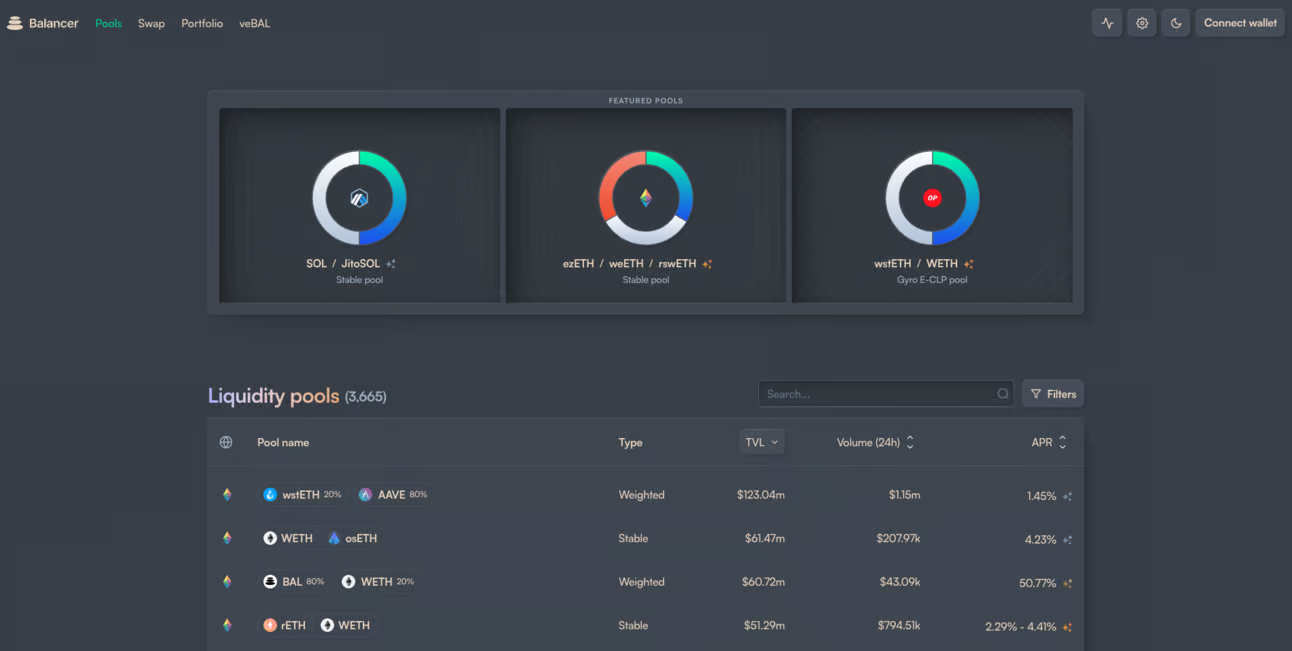

Balancer is a decentralized exchange (DEX) protocol that allows users to swap various cryptocurrencies directly from their wallets—without central authority or intermediaries.

Balancer uses an Automated Market Maker (AMM) model, where liquidity providers deposit token pairs into liquidity pools, and prices are determined mathematically based on the ratio of tokens in the pool. Users are incentivized to provide liquidity to earn a share of the trading fees generated within the pool.

Liquid Staking Protocols

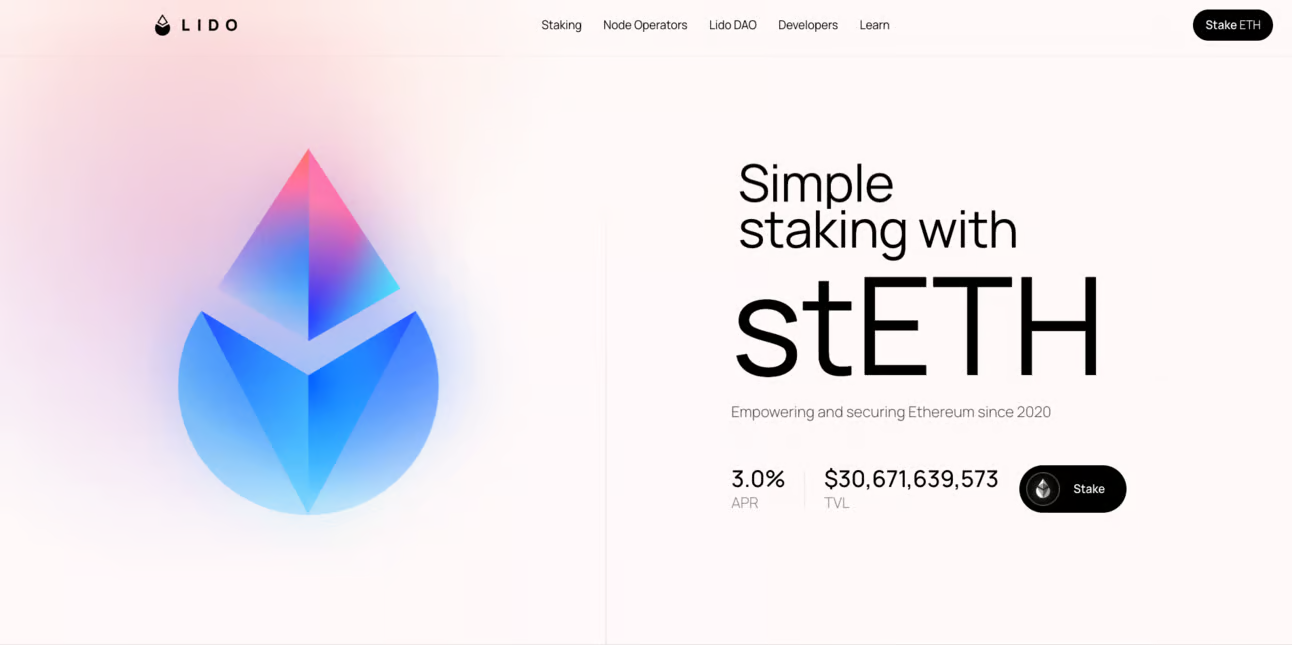

Lido Finance is a decentralized finance (DeFi) protocol offering liquid staking solutions for various proof-of-stake (PoS) blockchains.

Users can stake their assets through liquid staking protocols like Lido, which stakes on their behalf and returns a liquid asset—instead of locking up crypto in a staking contract.

This approach allows users to enjoy staking rewards while maintaining asset liquidity, enabling greater flexibility and participation across the DeFi ecosystem.

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations

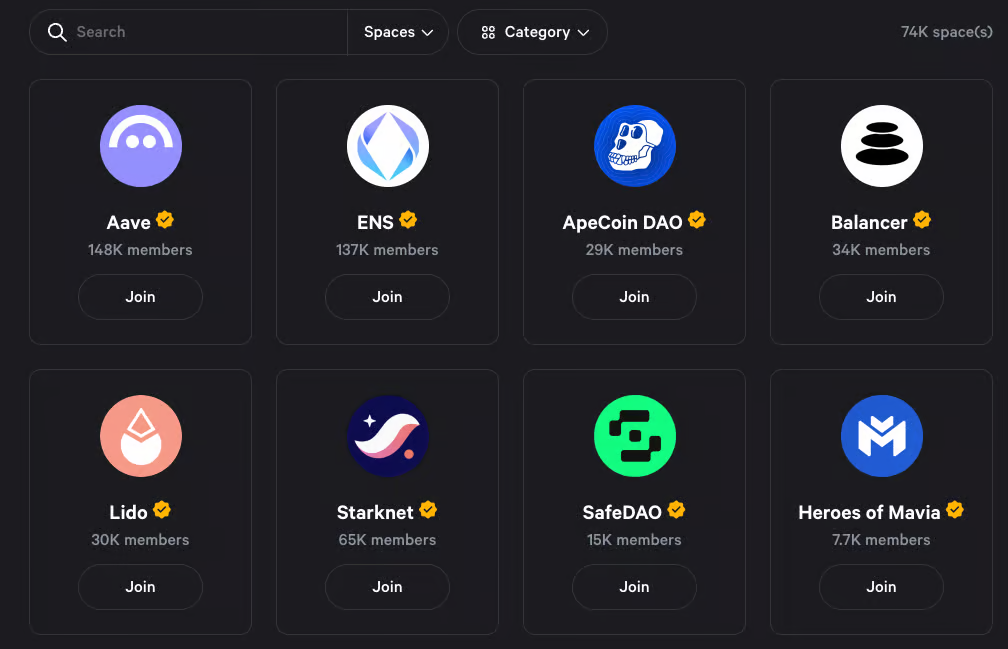

Thousands of financial applications have emerged based on decentralized principles, removing hierarchical power structures from traditional finance and replacing them with Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs).

DAOs are organizations that operate on blockchains, with rules and decisions encoded in computer programs rather than controlled by a central authority. Members typically hold governance tokens that grant voting rights, enabling them to propose and vote on matters such as fund allocation, financial management, and project development.

This decentralized structure ensures transparency, as all operations and transactions are recorded on the blockchain, and enables a more democratic decision-making process, distributing power among all members rather than concentrating it in the hands of a few.

Trustless Economy

We've covered a lot. Now let’s summarize and draw conclusions.

Cooperation is a hallmark of every great society, but when group size exceeds 150, the ability to build strong relationships weakens, replaced by reliance on narratives, stories, and centralized institutions.

While the formation of these entities allows groups to scale and build complex social structures, it also creates highly fragile organizations—where a single bad actor can exploit collective power for personal gain.

Game theory tells us that being good benefits societal growth. Yet history shows that a society of only good people is vulnerable to erosion by bad actors.

To achieve the next wave of broad and advanced cooperative societies, a new supporting structure is essential.

What’s fascinating about smart contracts is that they don’t attempt to build structure around an imperfect model—they completely redefine the model itself.

Today’s society concentrates trust in central institutions, but the introduction of smart contracts offers a new infrastructure—one that supports the development of next-generation, trust-minimized applications and services.—ChainLink

Like many others, I believe the global financial system and the livelihoods of every member of society cannot depend solely on the “good word” of those economically incentivized to manipulate truth for profit.

What about you?

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News