TeleportDAO: The Trade-off Between Security and Efficiency in Data Verification – Latest Practices in Light Node Design

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

TeleportDAO: The Trade-off Between Security and Efficiency in Data Verification – Latest Practices in Light Node Design

TeleportDAO is a project focused on cross-chain communication infrastructure between Bitcoin and EVM public blockchains.

Authors: Andy, Arthur

TL;DR

TeleportDAO and Eigen Labs have recently co-authored a research paper focusing on the security and efficiency challenges faced by light nodes when accessing and verifying on-chain data in proof-of-stake (PoS) blockchains. The paper proposes a novel solution—ensuring the security and efficiency of light nodes in PoS blockchains through economic incentives, insured pre-security mechanisms, customizable “programmable security,” and cost-effective measures. This approach is highly forward-looking and warrants in-depth exploration.

Note: Eigen Labs is the developer behind the restaking protocol EigenLayer and the data availability layer EigenDA. To date, Eigen Labs has raised over $150 million from prominent venture capital firms such as a16z, Polychain, and Blockchain Capital.

Based in Vancouver, Canada, TeleportDAO is an infrastructure project focused on cross-chain communication between Bitcoin and EVM-based public chains. The protocol recently completed a successful public sale via CoinList, raising $9 million. This funding round attracted participation from investors including Appworks, OIG Capital, DefinanceX, Oak Grove Ventures, Candaq Ventures, TON, Across, and bitSmiley.

Existing Challenges in Light Node Design

Currently, in PoS blockchains, validators participate in the consensus network by locking up a certain amount of staked tokens (e.g., 32 ETH in Ethereum), thereby securing the network. Thus, the security of PoS blockchains fundamentally relies on economic protection—the greater the total stake, the higher the cost or loss associated with attacking the consensus network. This slashing mechanism depends on a feature known as "accountability security," which allows for the penalization of validators who sign conflicting states.

Full nodes play a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of PoS blockchains. They store all transaction data, validate consensus signatures, replicate complete transaction histories, and execute state updates. These processes require substantial computational resources and sophisticated hardware. For example, running a full Ethereum node requires at least 2 TB of solid-state drive storage. In contrast, light nodes reduce computational demands by storing only block headers, making them suitable primarily for verifying specific transactions or states—such as in mobile wallets and cross-chain bridges. However, light nodes depend on full nodes to provide block information during transaction validation. Given that current node service providers are relatively centralized in market share, guarantees regarding security, independence, and timeliness remain incomplete. Therefore, this paper explores trade-offs between data acquisition costs and latency while achieving optimal security for light nodes.

Existing Designs for Light Nodes

Bitcoin introduced Simplified Payment Verification (SPV) as its light node protocol. SPV enables light nodes to verify whether a transaction is included in a specific block using Merkle proofs and block headers. As a result, light nodes need only download block headers and can verify transaction finality by checking block depth. In this case, the computational cost of consensus verification for light nodes in Bitcoin is relatively low. However, in PoS blockchains like Ethereum, consensus checks are inherently more complex. They involve maintaining the entire validator set, tracking changes in their stakes, and performing numerous signature verifications across the consensus network. On the other hand, the security of PoW light nodes relies on the assumption that most full nodes are honest. To address SPV's limitations, FlyClient and Non-Interactive Proofs of Proof-of-Work (NiPoPoW) provide clients with sublinear-cost proofs of block validity. However, their applicability to PoS consensus models is weak.

In contrast, PoS blockchains derive security from slashing mechanisms. This system assumes rational participants—attacks will not occur if the attack cost exceeds any potential profit. To reduce verification costs, Ethereum’s current light node protocol relies on a sync committee composed of 512 randomly selected Ethereum validators, each staking 32 ETH. However, the signing process within the sync committee is non-slashing. This design poses significant security flaws: dishonest signatures from the sync committee could mislead light nodes into accepting invalid data without penalty. Even if slashing were introduced, the total stake of the sync committee remains small compared to the vast Ethereum validator pool (as of March 2024, the number of Ethereum validators exceeded one million). Consequently, the security provided by this method cannot match that of the full Ethereum validator set. This model represents a special variant of multi-party computation under rational settings but fails to offer economically backed guarantees or mitigate threats from malicious, irrational data providers.

To address security and efficiency challenges during the PoS bootstrapping process, PoPoS introduced a segmented game to effectively challenge adversarial Merkle trees in PoS timing. While it achieves minimal space usage and avoids requiring clients to stay online continuously or maintain stakes, it does not resolve the issue of clients being able to go offline and rejoin the network without incurring significant costs.

Another research direction focuses on using zero-knowledge proofs to create succinct proofs. For instance, Mina and Plumo facilitate lightweight consensus verification through recursive SNARKs and SNARK-based state transition proofs. However, these methods impose considerable computational overhead on block producers and do not address compensation for potential losses incurred by light nodes. In the context of other PoS protocols—such as Tendermint used in Cosmos—the role of light nodes has been explored within their Inter-Blockchain Communication (IBC) protocol. Yet, these implementations are tailored to their respective ecosystems and are not directly applicable to Ethereum or other diverse PoS blockchains.

New Design for Light Nodes

Broadly speaking, the new design introduces an economic security module to achieve "programmable security," allowing light nodes to select different configurations based on their individual security needs. The security assumptions generally follow 1/N + 1/M—meaning the network remains secure as long as there is at least one honest and effective node among both the full nodes and the watchdog network.

Modules/Roles Involved

-

Blockchain: The protocol operates on a programmable blockchain with deterministic finality rules. For example, on Ethereum, a block achieves finality after at least two subsequent epochs, typically taking around 13 minutes.

-

Slashing Smart Contract: The protocol includes an on-chain slashing contract compliant with standard smart contract abstractions. It can access the block hash of the previous block in the blockchain. All parties can send messages to this contract.

-

Data Providers: Data providers run full nodes and track the latest blockchain state. They stake assets to offer services that verify the validity of requested states for light nodes. They sign all data sent to light nodes with keys corresponding to their public keys, thus authenticating the source and integrity of the data.

-

Watchdogs: Watchdogs are full nodes connected to light nodes to assist in data validation. Anyone can become a watchdog and earn rewards by monitoring and penalizing misbehaving parties. For simplicity, the following scheme assumes each light node is connected to at least one honest watchdog.

-

Light Nodes: Light nodes aim to verify the presence of specific states/transactions on the blockchain at minimal cost. During verification, they connect to a group of data providers and watchdogs.

-

Network: Data providers form a peer-to-peer (p2p) network that propagates data via Gossip protocol. Light nodes connect to several data providers to send requests and receive responses.

Scheme One: Security-First Approach

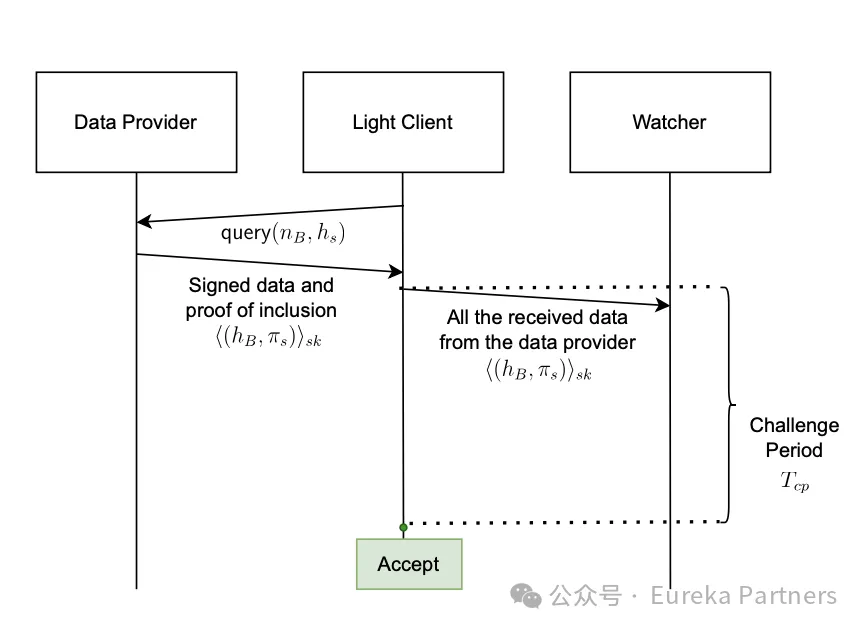

Scheme One ensures data credibility primarily through a challenge period and a watchdog network. In short, after receiving signed data from a provider, the light node forwards this data to the watchdog network for review. If fraudulent data is detected within the challenge period, the watchdog alerts the light node that the data is untrustworthy, and the slashing module in the smart contract confiscates the data provider’s stake. Otherwise, the light node accepts the data as credible.

Detailed workflow for light node data request:

-

The light node retrieves the latest list of data providers from the current network and sets a challenge period. Notably, the challenge period is independently determined per light node, though there is a universal upper limit. The challenge period defines the maximum time available for the watchdog network to verify data credibility; longer periods increase transaction transmission latency.

-

After obtaining the list, the light node selects a group of data providers, ensuring each has staked more than the value of the current transaction. Theoretically, higher stakes imply higher costs for malicious behavior, reducing trust risk for the light node.

-

The light node sends a data request to the selected providers, including the target block number and the inclusion proof for the desired state (transaction).

-

The data provider responds with the block hash and the transaction’s inclusion proof, along with a digital signature.

-

Upon receiving the data, the light node forwards it to the connected watchdog network. If no alert about data credibility is received by the end of the challenge period, the light node verifies the signature and passes the credibility test.

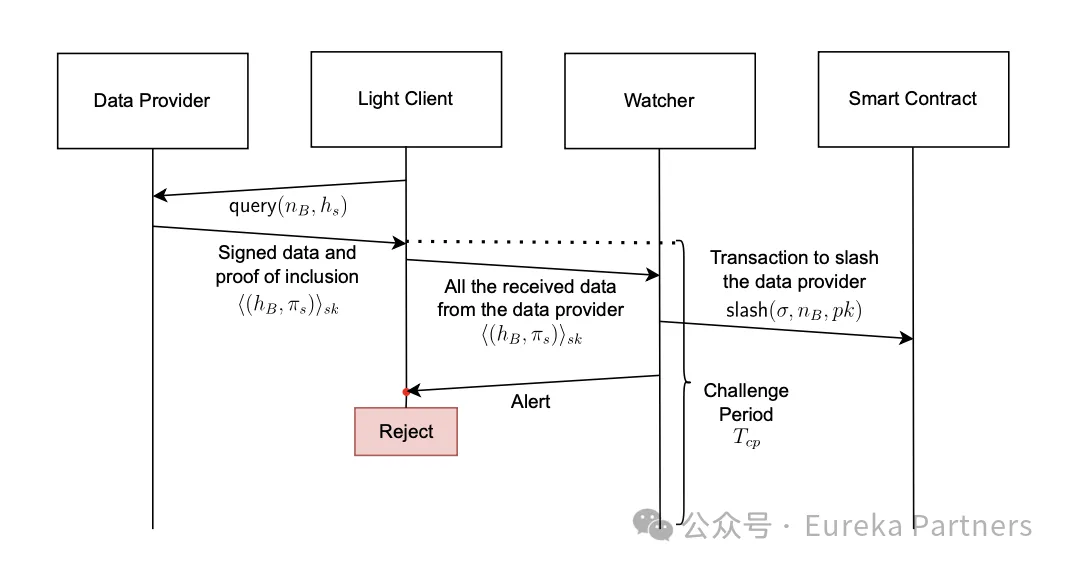

-

However, if an alert is received from the watchdog network, the light node must discard the previously received signature. The watchdog submits relevant evidence to the slashing module of the smart contract. If the contract confirms malicious activity, the data provider’s stake is slashed. Due to partial or complete slashing of selected providers, the light node must retrieve a new list of active providers to confirm that the slashing event occurred.

Additional Notes:

-

Any full node can join or leave the data provider network by submitting “registration” and “withdrawal” requests to the smart contract. There is a minimum staking threshold for registering as a data provider. Once a full node initiates withdrawal, its status immediately becomes “exiting,” and it stops receiving requests from light nodes to prevent fast-in-fast-out malicious behavior. Additionally, the data provider network periodically updates the list of currently active providers. During this update cycle, providers cannot withdraw funds—the withdrawal takes effect at the last block of the cycle. Update frequency exceeds the maximum challenge period to ensure all light nodes complete their data availability checks. Due to the dynamic nature of the provider network, light nodes must refresh the list of active providers in each update cycle. Extending the update cycle simplifies the verification process for light nodes (by predicting the current list based on prior registration/withdrawal records), but forces exiting nodes to wait longer before withdrawing.

-

After receiving a signed data packet, the watchdog network verifies that the signature belongs to the claimed provider and checks whether the data has been “finalized” in the consensus network. If the data does not appear on a valid chain, two scenarios may exist: first, the data has not yet been finalized on the current blockchain—different chains have different finality rules (e.g., longest chain rule); second, the transaction exists in a block on another valid chain. If falsification is detected, the watchdog network sends a slashing request to the smart contract, including the provider’s public key, signature, and block number, while simultaneously sending proof of the slashing event to alert the light node. Upon receiving this data, the smart contract compares the block number declared as finalized by the consensus layer against the received data. If inconsistent, slashing is triggered. Moreover, if a selected data provider gets slashed due to another request, the watchdog network promptly notifies the light node of reduced credibility, prompting the light node to obtain a new list and choose alternative providers.

Evaluation:

-

Security: By combining staking modules with a watchdog network, this scheme increases the cost of malicious behavior for both rational and irrational data providers, enhancing data credibility. However, since the entire protocol relies on the underlying consensus network (tested here on Ethereum), it faces potential trust issues if the consensus layer itself is attacked. Introducing a reputation mechanism could further mitigate systemic risks in extreme cases.

-

Full-node-level Security: This scheme aims to provide security assumptions equivalent to Ethereum’s PoS—i.e., false statements by full nodes carry slashing risks.

-

Network Liveness: If only a few rational data providers exist, light nodes may experience multiple rounds of delays. However, since each provider has non-zero throughput, every request will eventually be fulfilled. Thus, as long as one rational full node exists, the network remains operational. Furthermore, because provider rewards scale with stake size, this incentivizes full nodes to over-stake to protect the network.

-

Efficiency: The authors anticipate that Ethereum validators will be primary participants in the data provider network, as they already operate full nodes and can earn additional income. Small-value transactions might be verified via a single provider (requiring only one validation), while high-value transactions may require multiple providers (increasing verification linearly with the number of providers).

Scheme Two: Efficiency-First Approach

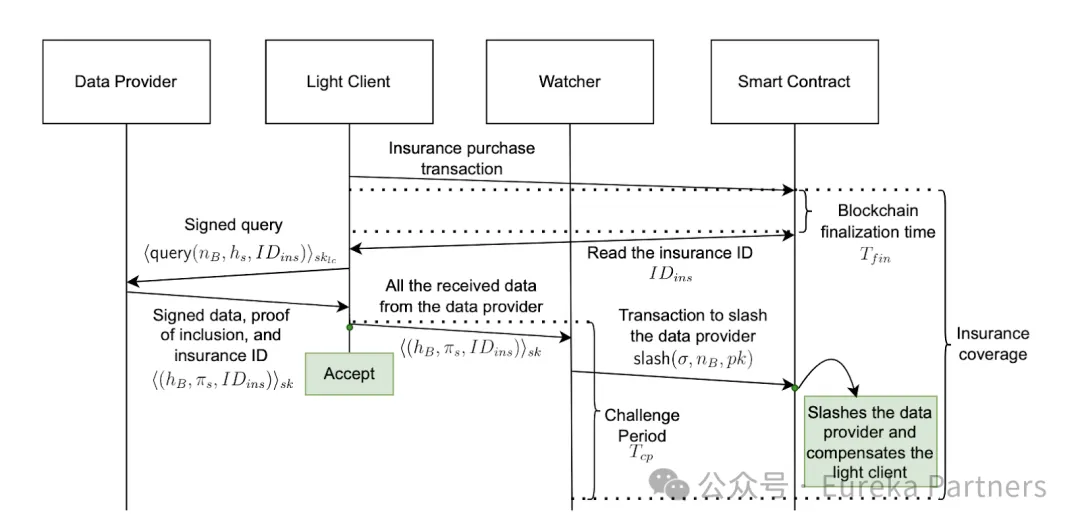

Scheme Two builds upon Scheme One by introducing an insurance mechanism to enable rapid data confirmation. In short, after determining the insurance amount and duration, part or all of a data provider’s stake can compensate the light node for losses resulting from malicious data. Thus, once the light node receives and verifies the provider’s signed data, it can consider the data initially trustworthy.

Detailed workflow for light node data request:

-

The light node calculates the potential maximum loss of the current transaction, then determines the insurance amount and policy duration. The amount of stake allocated by the data provider to back the insurance must exceed the insurance amount to ensure sufficient compensation funds.

-

The light node sets the challenge period for this transaction. Note that a single insurance policy can cover multiple inclusion checks. Therefore, the total challenge period chosen by the light node must not exceed the policy term, otherwise some transactions may fall outside coverage.

-

After setting parameters (insurance amount, policy duration, insured stake size, and preferred provider list), the light node sends a request to the smart contract. It then waits for block finalization time to verify whether the insurance purchase succeeded. Failure may occur if another light node selected the same provider earlier and consumed the remaining stake needed to meet the requirement.

-

The light node sends a data request containing the block number, target state (inclusion proof), and insurance ID.

-

The data provider sends the data and signature. The light node verifies the signature and forwards it to the watchdog network. At this point, the transaction is preliminarily trusted.

-

The watchdog performs initial verification upon receiving the data and signature. If malice is detected, it submits proof to the smart contract for slashing, and the penalty is distributed to the light node.

Additional Notes:

-

A data provider’s stake committed to insurance is isolated across different light node requests to prevent overlapping insurance claims. After a light node selects a provider, the smart contract locks the corresponding insured stake, preventing other light nodes from allocating that portion until the policy expires. If transactions are independent, the insurance amount equals the largest single transaction. Otherwise, it matches the total transaction value. With fixed total stake, light nodes generally prefer fewer providers to maximize verification efficiency.

-

Although data providers can initiate a “withdrawal” request before the insurance period ends, the withdrawal payout is only released after the policy expires.

-

Strictly speaking, the policy duration should exceed the sum of block finalization time, total challenge period, communication delay, and computation/validation delay. The more providers involved, the longer the required policy duration due to extended total challenge periods.

Evaluation:

-

Scalability: The scalability of Scheme Two depends on the total amount of tokens data providers are willing to commit to insurance.

-

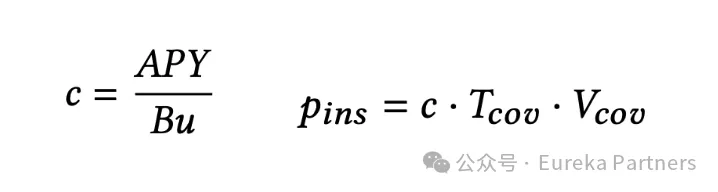

Insurance Cost: Higher security levels correlate with longer challenge periods, meaning providers must lock stakes for durations equal to or exceeding the challenge period. Hence, higher security demands lead to longer staking periods and higher fees paid by light nodes. Quantitatively, a provider’s staking cost is calculated as node revenue divided by (average annual staking utilization multiplied by total blocks per year). The price paid by the light node equals the staking cost multiplied by the policy duration and insurance amount.

Effectiveness of the Schemes

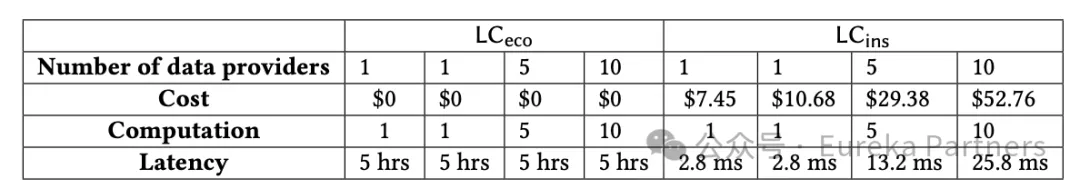

First, in terms of light node computational efficiency, both schemes demonstrate millisecond-level verification speed (the light node only needs to perform one verification).

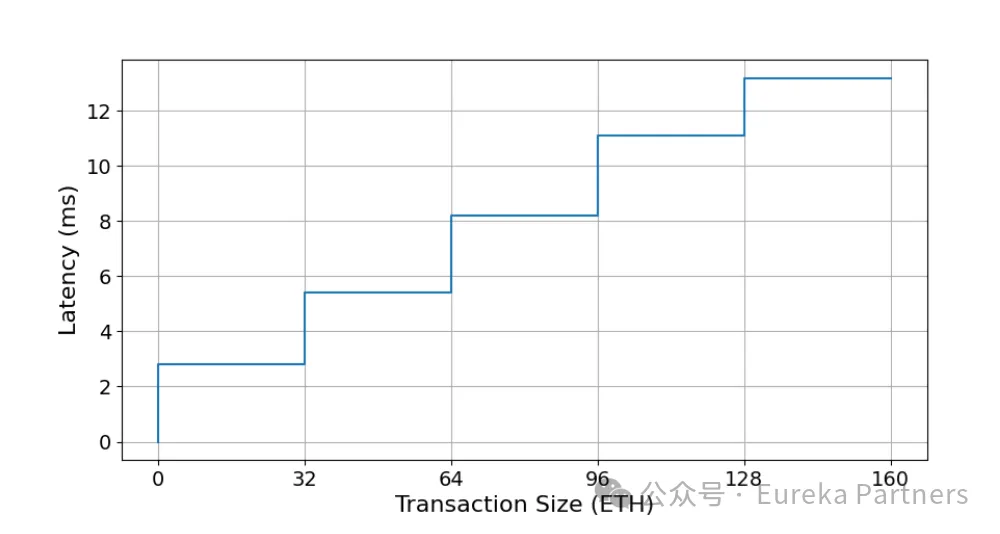

Second, regarding light node latency, under various experimental configurations (shown below), delays remain in the millisecond range. Notably, latency increases linearly with the number of data providers but stays within milliseconds. However, Scheme One involves waiting for the challenge period outcome, resulting in delays of up to 5 hours. If the watchdog network proves sufficiently reliable and efficient, this 5-hour delay could be significantly reduced.

Third, in terms of light node cost, actual costs include gas fees and insurance premiums, both increasing with insurance amount. Additionally, watchdogs are reimbursed for gas expenses via slashing proceeds, ensuring sufficient incentive to participate.

Future Extensions

-

Multiple Collateral Types: Currently, data providers stake ETH, but transaction values are denominated in USD. This means light nodes must constantly evaluate ETH exchange rates to ensure adequate collateral. Supporting multiple token types would give providers more staking options and reduce single-token exposure.

-

Delegation: Similar to merged mining, retail users could delegate their ETH to full nodes to participate in the data provider network, with rewards distributed according to predefined agreements—akin to Liquid Staking Derivatives (LSDs).

-

Block Proposal Guarantee: To avoid waiting for finalization periods (12–13 seconds in Ethereum), light nodes could use a guarantee mechanism to reduce waiting time. The light node adds a flag/symbol in the data request specifying the required guarantee type (finalized/proposed). Data providers respond with corresponding data and signatures. If a provider fails to deliver under a “proposed” guarantee, they face slashing.

Note: Proposed blocks may later be finalized or become uncle blocks. -

Costs and Fees: Watchdogs must stake a certain amount of tokens (greater than gas costs) to submit proofs to the smart contract. These proofs could be optimized using ZKPs to reduce fees. Under the insurance model, insurance premiums paid by light nodes go to data providers, while the watchdog network receives a portion of the slashing rewards from malicious providers.

-

Data Availability: Data providers are essentially full nodes who can not only participate in the consensus layer but also verify data availability. There are two approaches to availability verification: Pull model and Push model. The former involves light nodes randomly sampling data obtained from full nodes. The latter involves block proposers distributing different blocks to data providers. For pull-model providers, they are responsible for responding to sampling requests. After receiving the data, the light node forwards it to trusted nodes/validators, who attempt to reconstruct the block. If reconstruction fails, the provider is slashed. Building on this, the proposed light node protocol introduces an insurance mechanism, opening new avenues for data availability research.

Summary and Evaluation

The light node schemes proposed in this paper introduce “programmable security” to meet varying security requirements. Scheme One trades higher latency for enhanced security, while Scheme Two introduces an insurance mechanism to offer “instant confirmation” for light nodes. These solutions are applicable in scenarios requiring confirmation of transaction finality, such as atomic swaps and cross-chain applications.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News