ZK Rollups: The elephant in the room

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

ZK Rollups: The elephant in the room

For various types of DApps, ZK rollups may not be the optimal development stack choice.

Author: Jaehyun Ha

Translation: TechFlow

Summary

-

While zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) hold promise for creating a more private and scalable blockchain ecosystem, many aspects of zero-knowledge (ZK) technology are misunderstood or differ from common perceptions about its implementation.

-

ZKPs have two main aspects: "zero-knowledge" and "succinctness." While this statement is not incorrect, most ZK rollups only utilize the succinctness property—transaction data and account information are not fully kept zero-knowledge or private.

-

For various types of DApps, ZK rollups may not be the optimal development stack. For example, generating ZKPs can become a bottleneck for fast finality, degrading performance in Web3 gaming, while state-difference-based data availability methods may compromise services provided by DeFi lending protocols.

Figure 1: ZK is a great buzzword

Source: imgflip

The current state of the blockchain industry can be described as the era of zero-knowledge (ZK). Wherever you look, ZK is prominent, and it's becoming increasingly rare to find next-generation blockchain projects that do not incorporate ZK into their names. From a technical standpoint, there's no denying that ZK is a promising technology capable of contributing to a more scalable and private blockchain ecosystem. However, due to the complex technical background of ZK, many investors—both retail and institutional—often invest in ZK projects based on "belief" that it looks cool, novel, and potentially solves the blockchain trilemma, without fully understanding how ZK technology benefits each individual project.

In this ZK series, we will explore the hard-to-ignore drawbacks (disadvantages and limitations) of ZK rollups as well as their beneficial applications. First, we will break down the two core properties of zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) in blockchains: "zero-knowledge" and "succinctness." Then, we'll discuss why the vast majority of currently operational ZK rollups do not truly leverage the "zero-knowledge" aspect. Next, we'll examine areas where applying ZK rollups could be more harmful than beneficial, avoiding commonly known issues such as implementation complexity. Finally, we will highlight exceptional projects that effectively embody ZK principles and clearly benefit from using ZK technology.

Recap: Transaction Lifecycle in ZK Rollups

Rollups are scaling solutions that address Layer 1 (L1) throughput limitations by executing bundles of transactions off-chain and then storing summaries of the latest L2 state data on L1. Among them, ZK Rollups stand out by enabling fast fund withdrawals through submitting validity proofs of off-chain computations directly on-chain. Before diving into the problems of ZK rollups, let’s briefly review their transaction lifecycle.

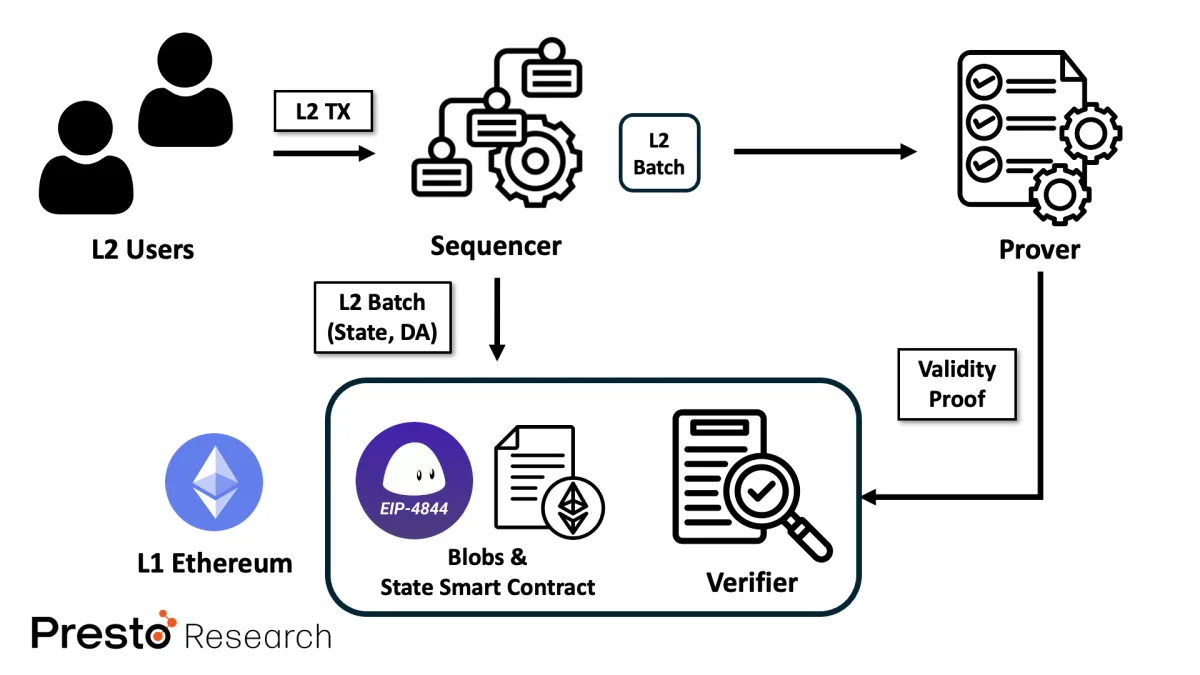

Figure 2: Transaction lifecycle in ZK rollups

Source: Presto Research Center

-

Each L2 user generates and submits their transaction to the sequencer.

-

The sequencer aggregates and orders multiple transactions, executes them off-chain to compute a new rollup state, then submits this new state as a “batch” to an on-chain state smart contract. It also compresses the corresponding L2 transaction data into data blobs to ensure data availability.

-

This batch is sent to a prover, which creates a validity proof (or ZKP) for the execution of the batch. The validity proof, along with auxiliary data (e.g., the previous state root), is then sent to a verifier smart contract on L1, helping the verifier identify what it is validating.

-

Once the verifier contract confirms the proof is valid, the rollup state is updated, and the L2 transactions within the submitted batch are considered finalized.

(Note: This explanation represents a simplified version of the ZK Rollup process; implementations may vary across protocols. If roles are distinguished, there could be additional entities in L2 such as aggregators, executors, and proposers. Data blob layers might also differ—blocks, block groups, batches—depending on their purpose. The above description assumes a scenario where a centralized sequencer holds strong authority to execute transactions and produces a unified data blob format as batches.)

Unlike Optimistic Rollups, thanks to ZKPs (such as ZK-SNARKs or ZK-STARKs), ZK Rollups can verify the correct execution of thousands of transactions by checking a single simple proof, without needing to replay all transactions. So, what exactly is this ZKP, and what characteristics does it have?

Two Properties of ZKPs: Zero-Knowledge and Succinctness

As the name suggests, a ZKP is fundamentally a proof. A proof can be anything that sufficiently supports a claim made by the prover. Suppose Bob (the prover) wants Alice (the verifier) to believe he has legitimate access to his laptop. The simplest way to prove this would be for Bob to simply tell Alice the password, allowing her to type it into the laptop and confirm Bob indeed has access. However, this verification process is unsatisfactory for both Alice and Bob. If Bob uses a very long and complex password, it would be extremely challenging for Alice to enter correctly (assuming she cannot copy-paste). More realistically, Bob likely wouldn’t want to reveal his password to Alice just to prove his access rights.

What if there were a verification process where Alice could quickly verify access to the computer without Bob revealing his password? For instance, Bob could unlock the laptop using fingerprint recognition in front of Alice, as shown in Figure 3 (note: this is not a perfect example of a ZKP). This is where both Alice and Bob can benefit from the two key properties of ZKPs: the zero-knowledge property and the succinctness property.

Figure 3: High-level intuition of zero-knowledge and succinctness

Source: imgflip

Zero-Knowledge (ZK)

The zero-knowledge property means that the proof generated by the prover reveals nothing about the secret witness (i.e., private data) beyond the validity of the proof itself, leaving the verifier completely unaware of the underlying data. In blockchains, this property can be used to protect individual user privacy. If ZKPs are applied to every transaction, users can prove the legitimacy of their actions (e.g., proving they have sufficient funds for a transfer) without exposing transaction details (such as transfers, account balance updates, smart contract deployments, and executions) to the public.

Succinctness

The succinctness property refers to ZK's ability to generate a short and quickly verifiable proof from a large statement—in other words, compressing something large into a compact form. In blockchains, this is particularly useful for rollups. Using ZKPs, a verifier in L2 can submit a succinct proof to a verifier in L1 to assert the correct execution of transactions (terabytes worth of transactions can be represented by a proof of just 10–100 KB). The verifier can then easily confirm execution validity in a short time (e.g., 10 milliseconds to 1 second) by verifying the succinct proof instead of replaying all transactions.

ZK Rollups Are Great—but Not Necessarily Private

The aforementioned properties of ZKPs are well-utilized in ZK Rollups. Although verifiers cannot infer original transaction data from the ZKPs they receive from provers, verifying the succinct proof allows them to efficiently validate the prover’s claim (i.e., the new L2 state). That said, claiming that current ZK Rollups fully adhere to both the zero-knowledge and succinctness properties is misleading. While this may be accurate when focusing solely on the interaction between prover and verifier, ZK Rollups involve other components such as sequencers, provers, and rollup nodes. Is the "zero-knowledge" principle guaranteed for them as well?

The challenge of achieving full privacy via ZKPs in any ZK Rollup lies in potential compromises that arise when some parts become private via ZK while others remain public. Consider the transaction lifecycle in ZK Rollups: is privacy maintained when transactions are sent from users to the sequencer? What about the prover? Or when L2 batches are submitted to the DA layer—is the privacy of individual account information protected? Currently, none of these conditions hold true.

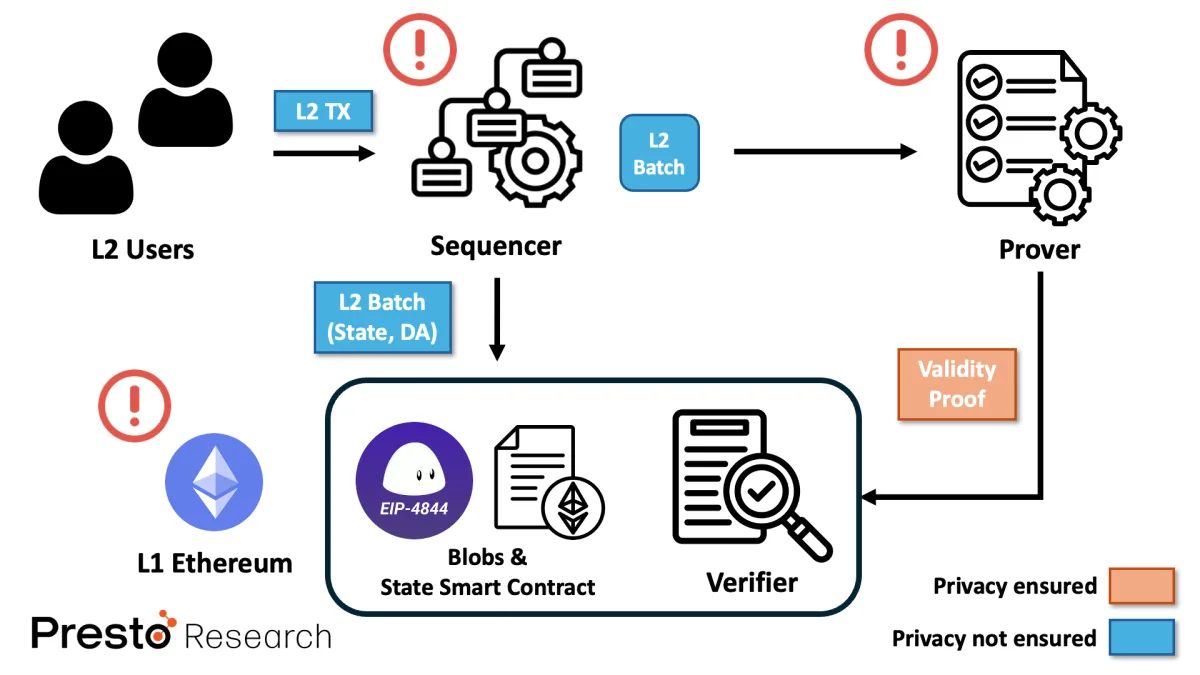

Figure 4: Privacy leaks in ZK rollups

Source: Presto Research

In most mainstream ZK Rollups, the sequencer or prover (or another centralized entity with significant authority) can clearly see transaction details including transfer amounts, account balance updates, contract deployments, and executions. As a simple example, you can easily observe all these details by accessing any ZK Rollup block explorer. Moreover, consider a scenario where a centralized sequencer stops operating and another rollup node attempts to restore the rollup state. It would extract information from the publicly published L2 data on the DA layer (in most cases, Ethereum L1) and reconstruct the L2 state. During this process, any node capable of replaying the L2 transactions stored on the DA layer could recover information about each user’s account state.

Therefore, the term "zero-knowledge" is implemented in a fragmented manner in current ZK Rollups. While this isn't necessarily wrong, it is clearly different from the common perception that “ZK means zero-knowledge equals full privacy.” The novelty of current ZK Rollups lies in leveraging the “succinctness” property rather than “zero-knowledge”—executing transactions off-chain and generating succinct proofs for verifiers so they can quickly and scalably verify execution validity without re-executing them.

For this reason, some ZK Rollups like Starknet refer to themselves as “validity rollups” to avoid confusion, while others ensuring true ZK privacy, such as Aztec, label themselves as ZK-ZK rollups.

A Closer Look at the Practicality of ZK Rollups

As previously mentioned, most ZK Rollups do not fully achieve ZK privacy. So what should our next step be? Should we aim to achieve complete transaction privacy by comprehensively deploying ZK across every part of the rollup? In fact, this is not a straightforward question. Beyond requiring significant technological advancements for further maturation, ZK still faces controversial issues regarding ideology (e.g., illegal use of private transactions) and practicality (e.g., is it actually useful?). Given that discussing the ethical implications of full transaction privacy goes beyond the scope of this article, we will focus on two practical issues encountered with ZK Rollups in blockchain projects.

Point 1: ZKP Generation Can Be a Bottleneck for Fast Finality

First, let’s discuss the practicality of ZK Rollups themselves. The most compelling selling point of ZK Rollups is shortened asset withdrawal times due to their “fast finality,” enabled by ZKPs. Higher TPS and lower transaction fees are additional benefits. The domain that best leverages the features of ZK Rollups is the gaming industry, where frequent deposits and withdrawals of in-game currency generate massive volumes of in-game transactions every second.

But are ZK Rollups truly the best tech stack for gaming? To answer this, we need to think deeper about the concept of “fast finality” in ZK Rollups. Imagine a user enjoying a Web3 game built on a ZK Rollup-based tech stack. The user trades in-game items for in-game currency and tries to withdraw those assets.

To withdraw assets, the in-game transaction must be finalized. This means the transaction must be included in a new rollup state commitment, the corresponding ZKP must be submitted to L1, and we must wait for the proof to finalize on Ethereum L1 to guarantee the transaction is irreversible. If all these processes happened instantly, we could achieve the much-hyped “instant transaction confirmation” of ZK Rollups, allowing users to immediately withdraw assets.

However, reality is far from that. According to finality time statistics for different ZK Rollups provided by L2beat, zkSync Era takes about 2 hours, Linea requires 3 hours, and Starknet averages around 8 hours. This is because generating a ZKP takes time, and including more transactions in a single batch (i.e., one proof) to reduce costs adds further delay. In other words, the speed of generating and submitting proofs becomes a potential bottleneck for achieving fast finality in ZK Rollups, which may degrade user experience in Web3 games.

Figure 5: ZKP generation could be a potential bottleneck for fast finality in ZK rollups

Source: imgflip

On the other hand, chains optimized for gaming like Ronin (supporting Web3 games such as Pixels and Axie Infinity) ensure ultra-fast finality at the cost of decentralization and security. Ronin is not a ZK-based or rollup-based chain—it is an EVM blockchain running under a PoA (Proof-of-Authority) + DPoS (Delegated Proof-of-Stake) consensus algorithm. It selects 22 validators based on delegated stake, and these validators generate and validate blocks via PoA (i.e., voting only among the 22 validators). Thus, on Ronin, transactions achieve rapid finality with almost no delay in block inclusion and short validation times. After the Shillin hard fork, the average transaction achieves finality in just 6 seconds. Ronin achieves all this without using ZKPs.

Of course, Ronin has its drawbacks. Being managed by centralized validators makes it relatively more vulnerable to 51% attacks. Additionally, since it doesn’t use Ethereum as a settlement layer, it cannot inherit Ethereum’s security. Cross-chain bridges also pose security risks. But from the user’s perspective—do they care? Even decentralized-order ZK Rollups today face single point of failure (SPOF) issues. Ethereum provides assurances by reducing the chance of transaction rollbacks, but if the centralized sequencer or validator fails, ZK Rollups can freeze too. Again, note that the “ZK” in ZK Rollups is only used to verify computational correctness. If another project offers the same functionality but faster and cheaper, ZK Rollups may no longer be the preferred tech stack for Web3 game users and developers.

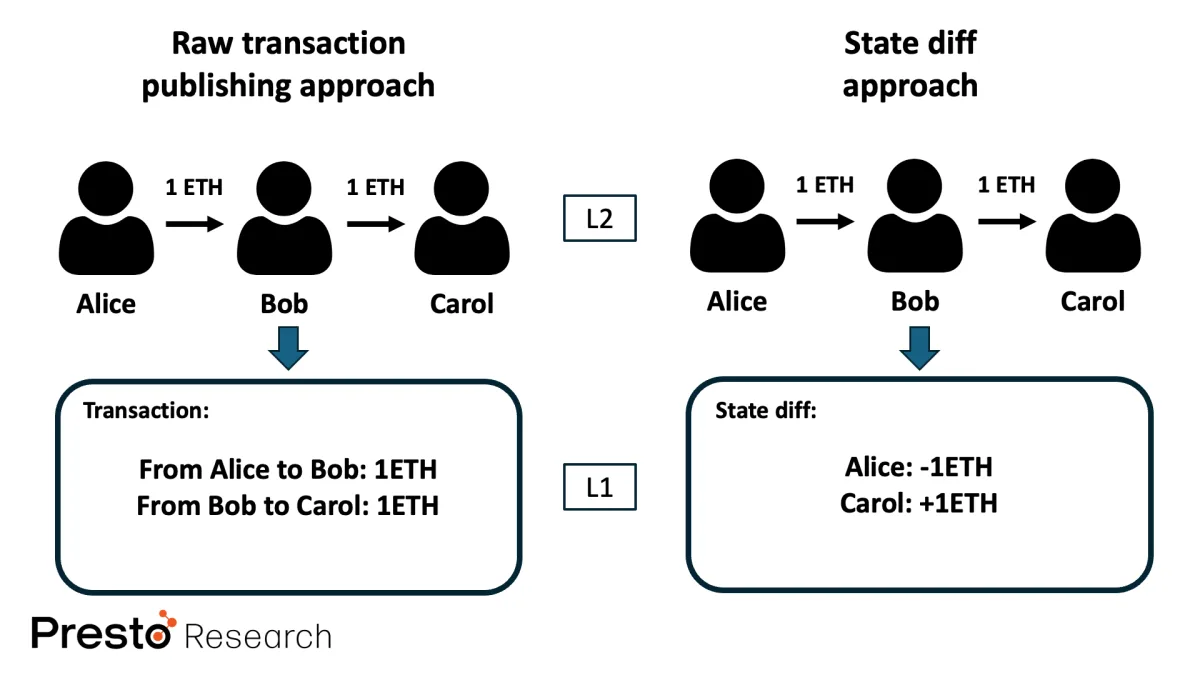

Point 2: Publishing State Differences Is a Double-Edged Sword

Another practical consideration concerns the implementation choices of ZK Rollup protocols. Here, we specifically focus on state difference publishing—one method used in ZK rollups to ensure data availability (see Unlocking Dencun Upgrade: Unseen Truth of Scaling DA Layers, Jaehyun Ha, 12Apr24).

A simple way to understand data availability in rollups is to imagine an amateur climber documenting their ascent of Mount Everest. The easiest method would be recording a video of every step from base camp to summit. Although the video file may be large, anyone could verify the climber’s journey and potentially replay the footage. This analogy corresponds to the raw transaction data publishing method for ensuring data availability. Optimistic Rollups follow this approach so individual challengers can replay and verify correct execution, as the sequencer’s state commitment cannot be trusted. In ZK Rollups, Polygon zkEVM and Scroll adopt this method, storing compressed raw L2 transaction data on L1 so anyone can replay L2 transactions if needed to restore the rollup state.

Returning to the amateur climber example, another verification method might involve a renowned climber accompanying the amateur up Everest to certify the climb was completed. Since the climb has already been attested by a trusted individual, the climber no longer needs to record every step. Simply taking photos at the starting point and the summit would suffice—others would accept that the climber reached the top. This metaphor reflects the state difference method for ensuring data availability. In ZK Rollups, zkSync Era and StarkNet adopt this approach, storing only the differences in L2 state before and after executing transactions on L1, so anyone can compute the state difference from the initial state if needed to restore the rollup state.

Figure 6: Raw transaction publishing vs. state difference publishing

Source: Presto Research

This state difference method is undoubtedly more cost-efficient than raw transaction data publishing, as it avoids storing intermediate transactions, thereby reducing L1 storage costs. Although this usually isn’t an issue, there is a potential drawback: this method does not allow recovery of the complete L2 transaction history, which could be problematic for certain DApps.

Take Compound, a DeFi lending protocol, as an example. Suppose it were built atop a state-difference-based ZK Rollup tech stack. Such protocols require full transaction histories to calculate supply and borrowing rates per second. But what happens if the ZK Rollup sequencer fails and another rollup node attempts to restore the latest state? It might successfully restore the state, but interest rates would be inaccurately reconstructed, as it can only track snapshots between batches—not each intermediate transaction.

Conclusion

This article primarily argues that the “ZK” in most current ZK Rollups does not truly exist, and in many cases, using ZKPs and ZK procedures in DApps may not be the optimal choice. ZK technology may feel unfairly blamed, as the technology itself isn’t flawed—it’s just that during the process of leveraging its technological advances, it may introduce potential performance degradation for DApps. However, this is not to say ZK technology is useless for the industry. When ZKPs and ZK rollups eventually mature technologically, they will certainly offer better solutions to the blockchain trilemma. In fact, there are already ZK-based projects today that maintain true ZK privacy, and many types of DApps effectively leverage the advantages of ZKPs and ZK rollups.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News