How does the decentralized social network Bluesky work?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

How does the decentralized social network Bluesky work?

Understanding atproto allows us to understand Bluesky.

By: Steve Klabnik

Translation: Kurt Pan

One of the reasons I'm excited about BlueSky is how it works. In this article, I'll explain some of its design and the principles I believe underlie it. I'm not a member of the BlueSky team, so these are just my personal views.

Let's begin.

Why does BlueSky exist?

Here’s what the BlueSky website currently says:

Social media is too important to be controlled by a few companies. We’re building an open foundation for the social internet so we can all shape its future.

That’s the big picture.

Okay, that sounds good—but what does it mean? Right now, BlueSky is a microblogging app, similar to Twitter and Mastodon. How does that fit into the bigger vision? While BlueSky is indeed a Twitter-like app, that’s not the whole story: BlueSky is the first application built to prove the feasibility of the Authenticated Transfer Protocol (shortened to AT, ATP, or “atproto”). BlueSky is the “building,” while atproto is the “open foundation for the social internet.”

An important point to note: BlueSky is also a company. Some people might look skeptically at a company saying, “Hey, we’re building something too big for any company to control!” I think that skepticism is healthy, but for me, the answer lies precisely in atproto.

The interaction between these two entities is crucial. We’ll start by exploring atproto, then discuss how BlueSky is built on top of it.

Is this cryptocurrency?

First thing we need to get out of the way: if you hear “Oh, it’s a distributed network called ‘some protocol,’” you might have alarm bells ringing—“Is this a cryptocurrency?”

Don’t worry—it’s not cryptocurrency. It does use some technologies originating from the crypto world, but it’s not blockchain, DAOs, NFTs, or anything like that. Just some cryptography and Merkle trees and such.

Overview of atproto

The AT Protocol Overview states:

The Authenticated Transfer Protocol, aka atproto, is a federated protocol for large-scale distributed social applications.

Let’s break this down:

Federated protocol

atproto is federated. This means different parts of the system can be run by multiple parties and still communicate with each other.

Choosing federation is a key part of atproto fulfilling its promise of being “too important to be controlled by one organization.” There are other aspects too, but this is a critical piece.

For large-scale

If you want to scale, you must design for scalability. atproto makes interesting choices to distribute system load more toward participants who can handle it, and less toward those who cannot. This allows apps built on atproto to scale smoothly to large user bases.

At least, that’s the hope. Earlier this week, BlueSky reached 5 million users and has been running far more stably than Twitter did in its early days. It’s not as large as many social apps, but it’s not insignificant either. We’ll see how it performs in practice.

Distributed social applications

atproto is designed for connecting with others, so it focuses on social applications. Currently, it’s also 100% public—no direct messages or private messaging. The reason is that implementing privacy in a federated system is extremely tricky; they’d rather get it right than release something with serious caveats. For now, it’s best used only for things you want to be public.

These apps are “distributed” because running them means operating directly on the network. There’s no single “BlueSky server”—only servers running atproto that exchange messages among themselves, including BlueSky messages and those from other apps people create.

That’s the overview—but what does this actually mean?

In atproto, users create cryptographically signed records to prove authorship. Records have schemas called Lexicons.

Records are stored in repositories. Repositories run as services exposed via HTTP and WebSocket, and can communicate and federate records with each other. These are commonly known as PDS—Personal Data Servers. Users either run their own PDS or use one hosted by someone else.

You can build applications by examining various records stored across the network and using them. These services are called App Views, as they expose specific views of information stored in the network. A view is created through the lexicon system: building an app means defining a lexicon that structures the data you want to handle, then viewing records using your lexicon and ignoring others.

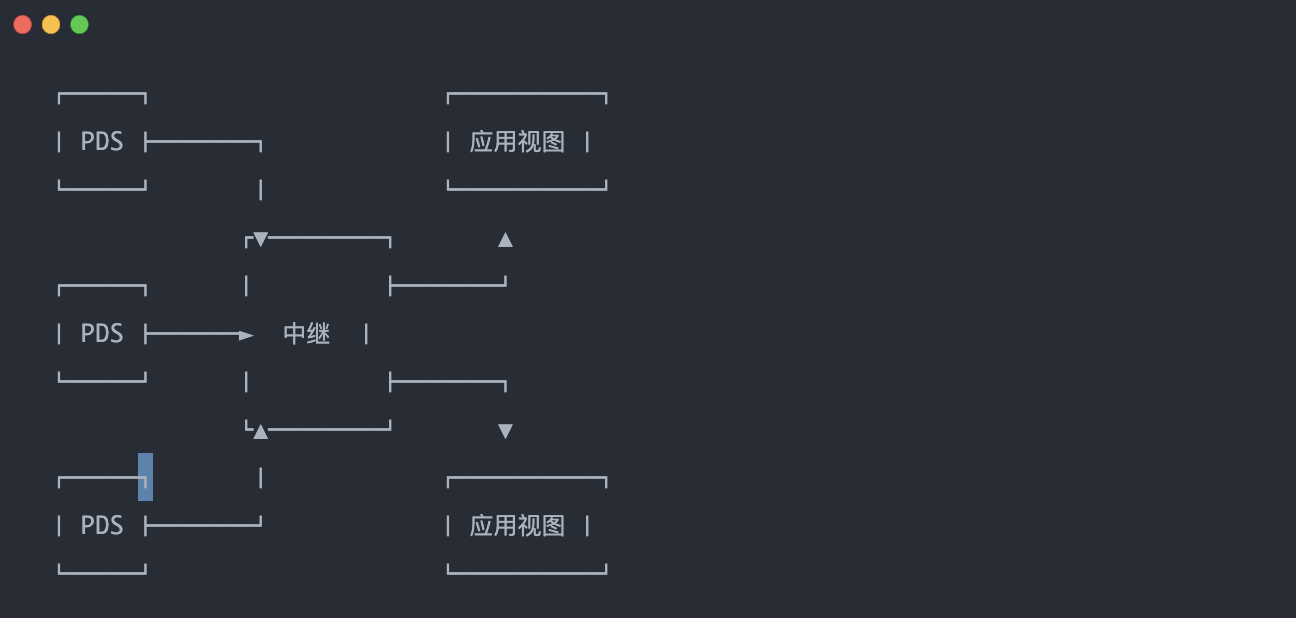

If this were all, severe scaling problems would arise. For example, if every time I post on BlueSky, my PDS had to send the post individually to each follower’s PDS, it would be highly inefficient and make running a popular PDS prohibitively expensive. To solve this, there’s an additional service called a Relay, which aggregates information across the network and rapidly broadcasts it widely to other relays. In practice, App Views don’t query repositories directly—they query Relays. When I post, my PDS notifies the Relay, and my followers’ App Views filter the Relay’s output to show only posts from people they follow. This does mean Relays are typically large and expensive to operate, but you could imagine running a smaller Relay that only propagates posts from a smaller subset of users. They don’t have to carry everything on the network—larger Relays usually do, but smaller ones may not.

Here’s an ASCII diagram:

This is essentially all you need to understand the core of atproto: people create data, data is shared across the network, and apps can interact with that data.

Other service types are being introduced, and more may come in the future. But before discussing those, we need to explore some ideological commitments to understand why things are designed the way they are.

What is 'speech and reach'?

Since atproto is intentionally designed for social applications, it must consider not only connecting people but also disconnecting them. Moderation is a core component of any social app: “no moderation” is still a moderation strategy. BlueSky acknowledges that people have different preferences regarding moderation, and that large-scale moderation is difficult.

Therefore, the protocol adopts a “speech and reach” approach to moderation. What we’ve described so far belongs to the “speech” layer—it purely concerns content replication on the network, regardless of semantic meaning. Moderation tools belong to the “reach” layer: you accept all speech, but provide ways to limit the visibility of content you don’t want to see.

Sometimes people say BlueSky is “completely free speech” or “does no moderation.” This is inaccurate. Moderation tools are built directly into the protocol so they work with all content on the network—even non-BlueSky apps. Additionally, you can choose your own moderators, so you aren't subject to others’ moderation choices. But I’m getting ahead of myself—let’s talk about Feed Generators and Labelers.

What is a Feed Generator?

Most social apps have the concept of a content “feed.” In atproto, this is broken out into its own service type called a Feed Generator. A typical feed example is: “Computer, show me posts from people I follow in reverse chronological order.” Recently, algorithmic feeds have become so popular in social networks that some non-technical users simply call them “the algorithm.”

A Feed Generator takes the massive data stream from Relays and filters/sorts it according to whatever criteria it chooses, presenting you with a curated list. You can then share these feeds with other users.

As a practical example, one of my favorite feeds is Quiet Posters, which shows posts from people who rarely post. This makes it easier to keep up with voices drowned out by my main feed. There are feeds like the ‘Gram that only show posts with images, or My Bangers, which displays your most popular posts.

To me, this is one of BlueSky’s killer features compared to other microblogging tools: full user choice. If I want to create my own algorithm, I can. I can easily share it with others. If you use BlueSky, you can access and follow any of these feeds.

Feeds are a recent addition to atproto, so while they already exist, they may not yet be fully polished, and could change in the future. We’ll see. From my perspective, they work quite well, though I haven’t looked deeply into the lower-level technical details.

What is a Labeler?

A Labeler is a service that applies labels to content or accounts. As a user, you can subscribe to specific Labelers, and your experience changes based on the labels applied to posts.

Labelers can operate however they like: automatically applying labels via algorithms on posts, manually via human raters liking/disliking content, or any method the operator chooses.

An example of a Labeler is a blacklist: tagging posts authored by people whose content you don’t want to see. Another example is a “not safe for work” (NSFW) filter, which might run an algorithm on images in posts and label them if deemed inappropriate for work.

Labelers already exist, but I don’t believe you can currently run your own. BlueSky runs its own, but to my knowledge, no external ones are publicly available yet. Once they are, though, you can imagine communities running their own services and adding whatever labels they want.

How does moderation work in atproto?

Putting it all together, here’s how moderation works: Feed Generators can transform feeds based on labels, or App Views can query Labelers, retrieve feeds, and apply transformations. These can be mixed and matched as desired.

This means you can customize your moderation experience not only across apps but within apps. Want a work-safe feed but allow NSFW content in another? You can do that. Want to create a personal blocklist and share it globally? You can do that too.

Because these moderation tools operate at the network level rather than the app level, they go further than other systems. If someone builds an Instagram clone on atproto, your blocklist Labeler would still work, since it operates at the protocol level. Block someone in one place, and if you wish, they’re blocked everywhere. Or maybe you subscribe to different moderation policies in different apps. It’s 100% up to you.

This model differs significantly from other federated systems, where you typically have an “account” tied to a single “instance,” as in Mastodon. So many people ask questions like “What happens when my instance gets de-federated?”—but such questions don’t quite apply here. You can achieve similar outcomes by blocking groups of users based on certain criteria. Maybe you dislike a particular PDS and want to ignore its posts—but that’s your personal choice, not dictated by a “server owner” where your account resides.

But how does identity work if you don’t have a home server?

How do identity and account portability work?

There are many intricate details about how identity works, so I’ll focus on what I believe matters most—and highlight controversial aspects, since they’re important.

At its core, users have an identifier called a “Decentralized Identifier” or DID. My DID looks like this: did:plc:3danwc67lo7obz2fmdg6jxcr. Feel free to follow! Of course, this isn’t the interface you usually see. Identity also involves a handle—a domain name. Unsurprisingly, my handle is steveklabnik.com. You’ll see my BlueSky posts come from @steveklabnik.com. The system also supports people without domains; if you sign up for BlueSky, you can pick a username, and your handle becomes @username.bsky.social. I started posting as @steveklabnik.bsky.social, then switched to @steveklabnik.com. But because DIDs are stable, my followers weren’t affected—they just saw the updated handle in the UI.

You can use a domain as a handle by taking the DID generated by your PDS and adding a TXT record in the DNS for that domain. If you’re not tech-savvy or don’t even know what DNS is, I envy you—but you can still use BlueSky’s partnership with NameCheap to register a domain and configure it as a handle without any technical knowledge. Then you can log into apps using your domain as a handle, and everything works seamlessly.

This is also how BlueSky enables real “account portability”—partly because, in practice, there’s no concept of an “account.” A person using a given DID cryptographically signs their content, which is then replicated across the network. Your “account” can’t truly be banned, because that would require forcibly stopping you from using a key they can’t even access. If your PDS fails and you want to migrate to a new one, there’s a mechanism to refill your PDS content from the network itself and notify the network of your move. This is genuine, meaningful account portability, fundamentally different from any similar service today.

But.

The devil is in the details, and I think this is one of the more meaningful criticisms of BlueSky and atproto.

You see, there are multiple “methods” for creating DIDs. BlueSky supports two: did:web, based on domains. This method has some drawbacks—I personally don’t fully understand them yet, so I can’t describe them well, but I believe I’ll write more deeply about DIDs later.

Due to those weaknesses, BlueSky implemented its own DID method called did:plc. “plc” stands for “placeholder,” reflecting that despite plans to support it indefinitely, it has weaknesses. The flaw is that resolving correct information requires querying a service run by BlueSky. For example, here’s my query. This means BlueSky could ban you in more severe ways than would be possible in a fully decentralized network design, which some consider a serious issue.

Is this flaw fatal? I don’t think so. First, if you really don’t want to participate, you can use did:web. Yes, it has its own issues—that’s why did:plc was created. But you can work around it.

Second, in my view, the BlueSky team has shown sufficient awareness and discomfort with this central control. The design allows you to transition to better systems if they emerge. They’ve also said transferring governance of did:plc to some consensus model in the future is possible. Options exist. Others could even run their own did:plc services and use them if they choose.

Personally, I see this as pragmatic management; others see it as a sinister plot. You’ll have to decide for yourself.

How is BlueSky built on atproto?

Now that we understand atproto, we can understand BlueSky. BlueSky is an application built atop the atproto network. They run an App View and a web app that uses that App View. They also operate a PDS for users who register via the web app, plus Relays that communicate with those PDS instances.

They’ve published two lexicons: one under com.atproto.* (low-level operations needed by any app on the network), and another under app.bsky.* (BlueSky-specific operations).

One particularly nice thing about BlueSky is their product goal: no one should need to know these nerdy details to use BlueSky. No instances mean no “choose an instance to create an account” flow, and portability means if my host fails, I can migrate seamlessly—my followers won’t even notice.

How can others build apps on atproto?

You can create an atproto app by defining a lexicon. Then you need to run an App View to process network data related to your lexicon, and your app will let users write data into their PDS using your lexicon.

I’m considering doing this myself. We’ll see.

Conclusion

Alright, technically speaking, that’s an overview of how atproto and BlueSky work. I find this design very clever. I also think it makes sense to distinguish between atproto and BlueSky, because having a “killer app” on the network gives people a reason to use it. It also serves as a test to ensure atproto is robust enough to build real applications.

I’m sure I’ll have more to say about all this in the future.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News