A Brief Discussion on Redstone: It's Not Plasma, But a Variant of Optimium

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

A Brief Discussion on Redstone: It's Not Plasma, But a Variant of Optimium

This article will introduce the principles of Plasma, explain why it is unfriendly to smart contracts and DeFi, and clarify what Redstone actually is.

Author: Faust, GeekerWeb3

Recently, a project called Redstone has become a hot topic. Launched by the Lattice team as a gaming-focused Layer2 infrastructure, Redstone officially launched on November 15 and is now live on testnet. Interestingly, the Lattice team describes "Redstone as an Alt-DA chain inspired by Plasma."

The day before Redstone’s launch, Vitalik published an article titled “Exit games for EVM validiums: the return of Plasma,” which briefly revisited the once-forgotten Ethereum scaling solution “Plasma,” suggesting that validity proofs (confused here with ZK proofs) could be introduced to resolve Plasma’s issues.

Some believe Vitalik wrote this article to endorse Redstone—some even speculate in the GeekerWeb3 community that he might have invested in it. Combined with the ongoing debate over “Layer2 definitions on Ethereum,” many now expect a “Plasma revival,” potentially undermining external DA solutions like Celestia, since Plasma does not impose strict data availability (DA) requirements.

However, according to the author's research, Redstone does not align with Plasma’s core framework; its claim of being “inspired by Plasma” may simply be capitalizing on the buzz around Vitalik’s article, rather than indicating actual endorsement from Vitalik. Moreover, Redstone’s DA challenge mechanism closely resembles the approach introduced by Metis, a Layer2 project, back in April 2022—except that they differ in the order of updating the state root and publishing DA data.

Therefore, the public may have “overinterpreted” Redstone. The following sections will use simple reasoning to explain how Plasma works, why it is unfriendly to smart contracts and DeFi, and what Redstone actually is.

Plasma: Emergency withdrawals required upon data withholding attacks

Plasma dates back to Ethereum’s ICO boom in 2017, when user demand surged and ETH’s low TPS became a bottleneck. At that time, the initial theoretical version of Plasma was released, proposing a Layer2 scaling solution capable of handling “almost all financial scenarios worldwide.”

In short, Plasma is a scaling solution that only posts Layer2 block headers/Merkle roots to Layer1, while the rest of the data (DA data) is published off-chain. If the Plasma sequencer/operator submits a Merkle root on L1 that includes invalid transactions (e.g., incorrect digital signatures), affected users can submit fraud proofs to challenge the validity of that root.

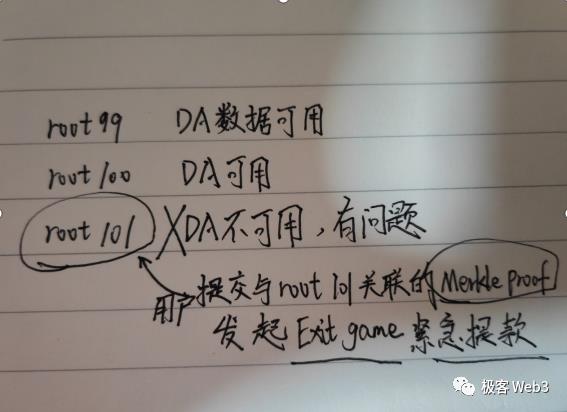

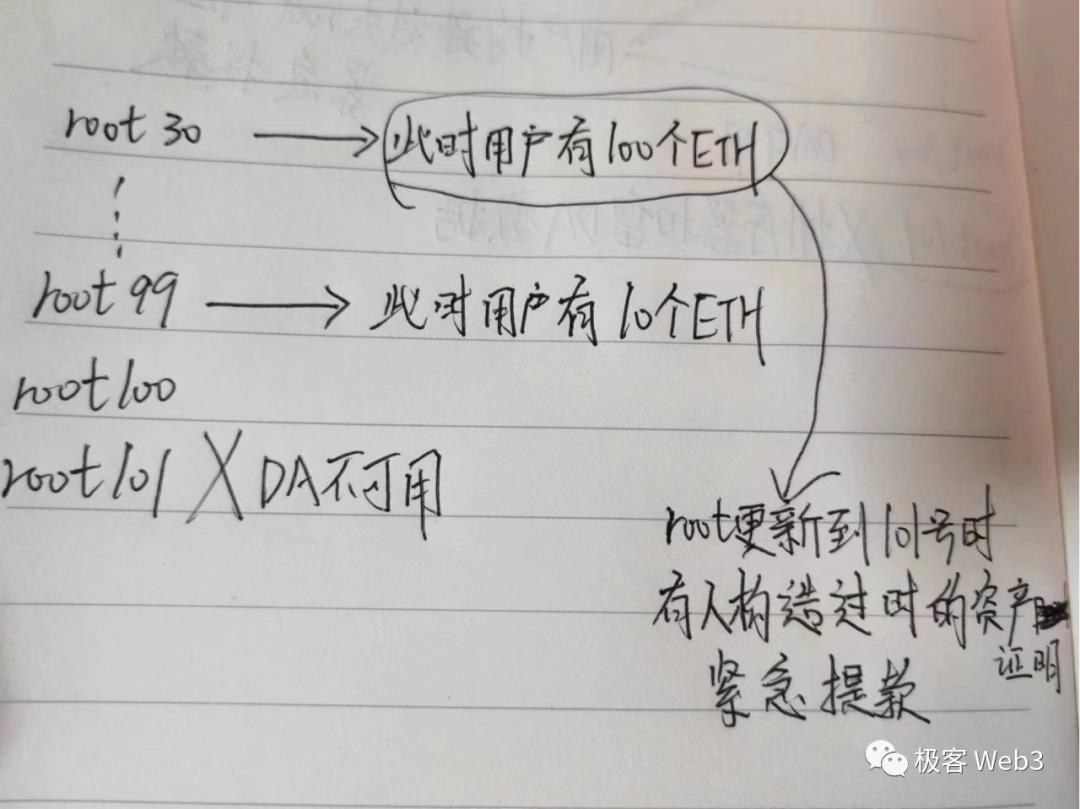

The problem is, submitting a fraud proof requires access to the DA data—but Plasma imposes no strict DA guarantees, so there's no assurance that users or L2 nodes can obtain the data. If the sequencer launches a data withholding attack (also known as a data availability issue)—posting new block headers/Merkle roots without releasing the corresponding block bodies—users cannot verify whether the roots are valid. In such cases, users must assume the sequencer is compromised and initiate an emergency withdrawal via the “Exit Game” mechanism to move assets from Layer2 back to Layer1.

This process requires users to submit a Merkle proof showing they indeed hold certain assets on L2—we can call this an "asset ownership proof." Interestingly, Plasma’s Exit Game differs from ZK Rollup’s “escape hatch” mode: ZK Rollup users must submit a Merkle proof corresponding to the most recent valid state root, whereas Plasma users can submit proofs based on much older Merkle roots.

Why is it designed this way? Because in ZK Rollups, submitted state roots are immediately validated by a contract on Layer1 (checking if the validity proof is correct). If the recently submitted state root is valid and legitimate, users should provide a Merkle proof tied to that valid root as their asset proof.

But in Plasma, the sequencer-submitted Merkle roots cannot be automatically verified by Layer1 contracts. Instead, L2 nodes must actively challenge invalid roots, hence the need for a challenge mechanism. This makes Plasma fundamentally different from ZK Rollups in operation.

Suppose the sequencer just published an invalid Merkle Root 101 and simultaneously launched a data withholding attack, preventing L2 nodes from proving Root 101 is invalid. Users can then submit a Merkle proof based on Root 100 or earlier to withdraw their assets.

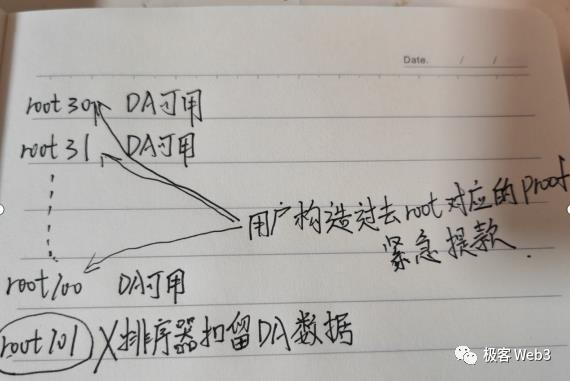

Of course, there's a catch: a user might submit an asset proof based on Root 30 or even earlier, requesting withdrawal—even though their balance may have changed after Root 30 was published. In other words, they’re submitting an outdated asset proof, enabling classic double-spending.

To address this, Plasma allows anyone to submit a fraud proof against such withdrawal attempts, showing that a particular user’s “asset proof” is outdated. By enabling “anyone can challenge another’s withdrawal,” Plasma avoids needing complex processing of urgent withdrawal requests like ZK Rollups do.

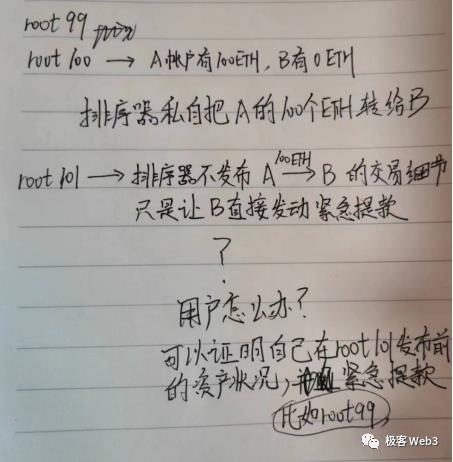

Yet one scenario remains: the sequencer could first transfer others’ assets into its own L2 account, then launch a data withholding attack to prevent challenges. Then, the sequencer initiates an emergency withdrawal, submitting an “asset proof” claiming rightful ownership of those assets.

Clearly, due to missing historical records, it becomes hard to directly prove the sequencer’s asset origin is illegitimate. How to handle this? Early Plasma versions like Plasma MVP anticipated this and introduced “withdrawal priority.” Withdrawal requests tied to earlier roots get processed first.

If the sequencer cheats at Root 101 and tries to withdraw, users can submit asset proofs based on Root 99 or earlier to exit. As long as the sequencer can’t alter historical records already posted on Layer1, users have a way out.

But Plasma still has a fatal flaw: whenever a data withholding attack occurs, users must rely on emergency withdrawals (Exit Game) to protect their funds. If too many users try to exit simultaneously, Layer1 may become overwhelmed.

More critically, who withdraws assets locked in DeFi contracts? Suppose someone deposited 100 ETH into a DEX liquidity pool. Later, the Plasma sequencer fails or acts maliciously, triggering mass withdrawals. But their 100 ETH remains under control of the DEX contract. Who moves these assets to Layer1?

Ideally, users would first redeem their assets from the DEX pool and then withdraw them to L1. But the problem is, the Plasma sequencer is already faulty/malicious, so redemption transactions can’t be executed. Alternatively, allowing the DEX contract owner to withdraw controlled assets to L1 would effectively grant them ownership—they could withdraw everything and disappear. That’s clearly unacceptable.

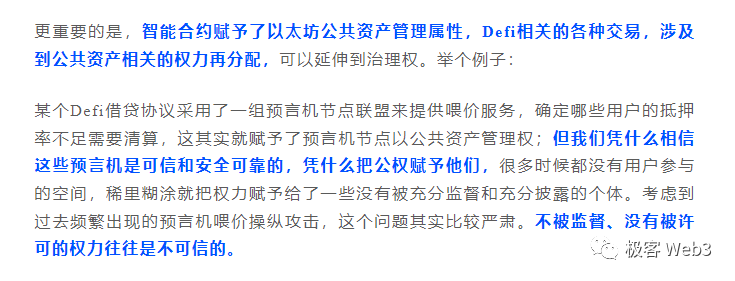

Thus, handling “public assets” controlled by DeFi contracts becomes a massive unresolved risk. One workaround could be rebuilding mirrored DeFi contracts on Layer1 via social consensus, but this introduces enormous complexity and opportunity costs. Deciding who votes on how these mirror contracts are managed raises major governance issues—essentially a question of power distribution, which Xiangma discussed in his interview titled "High-performance public chains struggle to innovate; smart contracts involve power allocation."

Vitalik also acknowledged this in his recent article, highlighting it as one reason Plasma is unsuitable for smart contracts. Well-known Plasma variants like Plasma MVP and Plasma Cash adopted UTXO or similar models instead of Ethereum’s account-based model and excluded smart contract support—avoiding the “asset ownership assignment” issue. While each UTXO’s ownership clearly belongs to individual users, UTXOs themselves come with various limitations and are inherently incompatible with smart contracts. Hence, Plasma works best for simple payments or order-book exchanges.

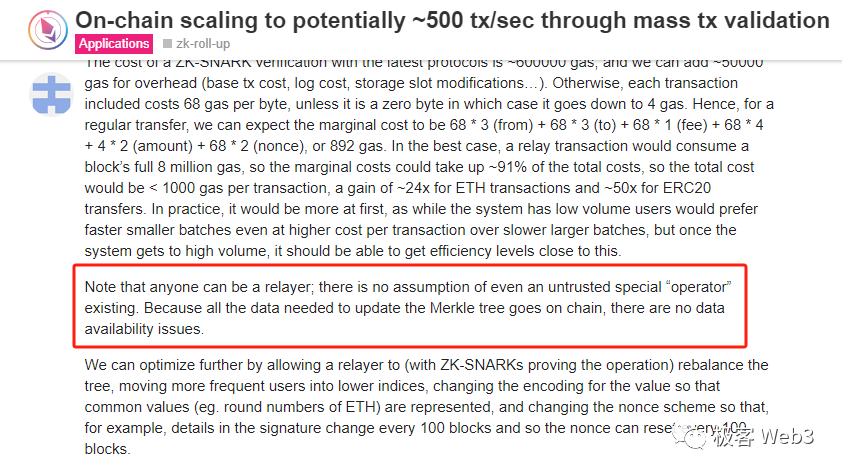

Eventually, as ZK Rollups gained popularity, Plasma faded into history, because Rollups avoid Plasma’s data withholding problem entirely. If a ZK Rollup sequencer withholds data—posting only the state root to Ethereum without DA data—the root will be deemed invalid and rejected by the verifier contract on L1. Thus, any valid state root in a ZK Rollup must have its corresponding DA data available on Ethereum. This eliminates the possibility of “publishing only block headers or Merkle roots without the block bodies,” solving the data availability issue/data withholding attack.

Moreover, historical DA data in Rollups is permanently stored on Ethereum, enabling anyone to reconstruct and sync a full L2 node using Ethereum’s blockchain history. This significantly lowers the barrier to decentralized and permissionless sequencer designs. In contrast, Plasma’s lack of DA guarantees makes achieving decentralized sequencers much harder—to enable replaceable decentralized sequencers, all L2 nodes must agree on the same block, which demands strong DA mechanisms.

Additionally, if a ZK Rollup sequencer attempts to include invalid transactions in a Layer2 block, it will fail—guaranteed by the validity proof system.

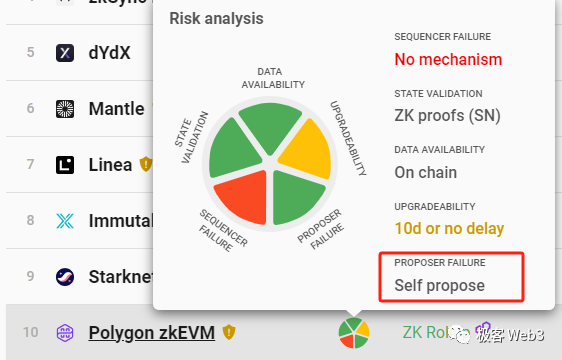

Ultimately, the scope for sequencer misbehavior in ZK Rollups is far narrower than in Plasma: at worst, the sequencer can stall state root updates (equivalent to downtime) or censor certain transactions. Furthermore, if a Rollup sequencer fails, other nodes can take over more easily. In ideal conditions, Rollups can reduce the need for emergency exit mechanisms (called escape hatches in ZK Rollups) to near zero.

(L2BEAT's "Proposer Failure" section shows how different L2s handle sequencer failures. "Self Propose" typically means other nodes can replace a failed sequencer.)

Today, almost no teams in the Ethereum ecosystem continue pursuing Plasma—nearly all Plasma projects have been abandoned.

(Vitalik explains why ZK Rollups are superior to Plasma, including points on permissionless sequencer operation and DA issues)

What is Redstone? It’s not Plasma—it’s a variant of Optimium

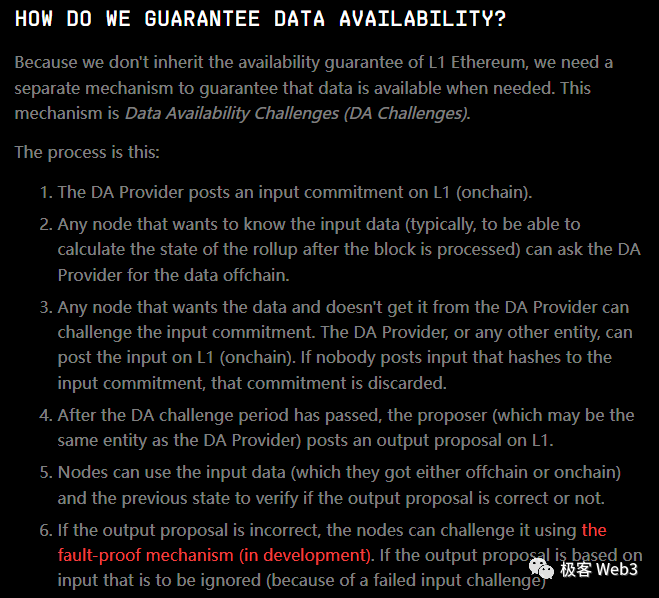

We’ve summarized Plasma and why it was superseded by Rollups. Now regarding Redstone, you likely see key differences: Redstone solves the data withholding attack problem. For example, it doesn’t immediately post a new state root. Instead, it first publishes raw DA data off-chain, then posts the datahash (as a commitment) on Ethereum, asserting that the full data corresponding to this hash has been published off-chain.

(Redstone’s official explanation of its anti-data-withholding mechanism)

Anyone can challenge Redstone’s sequencer, claiming it hasn’t published the raw data corresponding to a given datahash. In response, the sequencer must publish the data on-chain to counter the challenge. If the sequencer fails to timely publish the data on Ethereum after being challenged, its previously posted datahash/commitment is considered invalid.

If the sequencer responds promptly, challengers can retrieve the raw DA data linked to the datahash. Ultimately, nearly all L2 nodes can obtain the necessary DA data, resolving the data withholding issue. Of course, challengers must pay a fee upfront—approximately equal to the cost the sequencer incurs posting raw DA data on Ethereum—to prevent malicious actors from launching free, frivolous challenges that harm the sequencer.

Finally, after the challenge period for a datahash ends, the sequencer posts the corresponding state root—i.e., the root resulting from executing the transaction sequence contained in the DA data. At this point, L2 nodes can use fraud proofs to challenge invalid roots. If a previous datahash was challenged and the sequencer failed to publish the raw data, then even if it later posts the corresponding state root, it will be deemed invalid.

Since Redstone publishes DA data before posting the final valid state root, it directly prevents data withholding attacks (where the sequencer posts only the root without DA data).

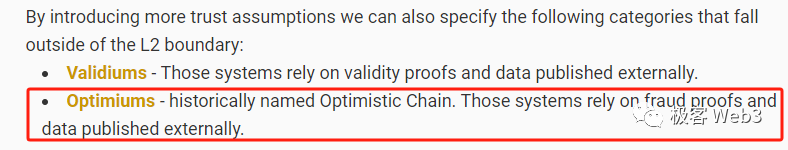

This model clearly differs from standard Optimium (OP Rollups that don’t use Ethereum for DA, like Arbitrum Nova). Optimium typically relies on an off-chain DAC committee to ensure data availability, with the DAC periodically submitting a multi-sig transaction on-chain. Upon receiving it, the L1 Rollup contract assumes the latest batch of DA data has been published off-chain.

(Source: L2beat)

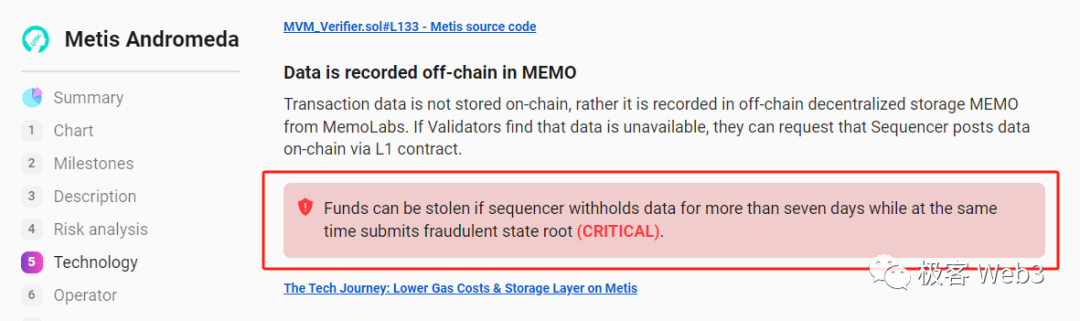

Projects like Metis and Arbitrum Nova submit both the state root and datahash simultaneously. If someone suspects data withholding, they can initiate a challenge, prompting the sequencer to post the DA data on-chain.

Thus, the key difference between Redstone and Metis lies here: Redstone first posts the datahash, waits for the DA challenge period to end, then posts the state root; Metis posts both state root and datahash together, only posting DA data on-chain if challenged. Clearly, Redstone’s approach is safer, because under Metis’ model, if the sequencer ignores DA data challenges, the data withholding issue can’t be resolved quickly—forcing reliance on emergency withdrawals, social consensus, or node replacement.

Under Redstone, however, if the sequencer withholds data, its posted state root is automatically invalidated—making state root and DA data interdependent. This gives Redstone DA assurances much closer to Rollups, making it essentially a superior variant of Optimium compared to Arbitrum Nova or Metis.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News