Deep Dive into the Friend.tech Economic Model: Game Theory, Expected Value, and Demand Curves

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Deep Dive into the Friend.tech Economic Model: Game Theory, Expected Value, and Demand Curves

The best way to understand an economic model is to put yourself in the project team's shoes—if I were designing the economic model, how would I do it?

1. How to Build a Ponzi Social Product

The economic model of Friend.tech appears extremely simple:

(1) Key price increases with quantity;

(2) A 10% fee is charged on every transaction, split equally between the protocol and the Key issuer;

(3) Points will be distributed to users over the next six months.

The best way to understand an economic model is to put yourself in the project team’s shoes: 【If I were designing this model, what would I do?】 Our starting point is building a SocialFi product. Given past experiences and the current abundance of market liquidity, it's hard to remain optimistic—so we aim for a product with some Ponzi characteristics to enable cold start.

(1) What Does (S²)/16000 Mean?

At its core, a Ponzi scheme rewards early entrants. Assuming users enter one by one and S can only take integer values, we should use difference and summation analysis. We observe that ΔP/ΔS increases linearly, ensuring that as the number of Keys grows, so does their price—and at an accelerating rate (i.e., faster price increases over time).

Clearly, this is a highly indirect yet efficient Ponzi curve: each new entrant pushes prices higher, and the magnitude of each push increases over time. The choice of 16000 is also logical—we need a parameter to align S and P with realistic market expectations. As shown below, if the value were smaller, the P curve would become too steep, causing excessive price volatility; if larger, the curve would flatten, reducing the Ponzi effect. Thus, 16000 represents a balanced compromise. Its relatively low capacity also matches current market liquidity conditions.

(2) How the Economy Cycles

Optimists see Friend.tech as a social platform; pessimists view it as a gambling platform. However, both interpretations share three roles: 1) the FT platform, 2) Key issuers, and 3) users. The only profit-generating activity is user trading (which also serves as a prerequisite for usage or holding).

So the real question becomes: how do we attract users to buy? From a social platform perspective, Key issuers are service providers (regardless of the specific service), while the platform offers foundational infrastructure. From a gambling perspective, Key issuers act like "bookies," recruiting players.

This revenue-sharing model is elegantly efficient—50% goes directly to incentivizing KOLs, which explains why many influencers have embraced it. The reason for adopting a Ponzi-like mechanism lies in solving the cold-start problem: initially, services provided by Key issuers are inconsistent and unstable, so speculative demand fills the gap during early stages.

(3) Points Airdrop

There isn’t much to say about points—they primarily serve to further stimulate demand and blur the lines between speculation, utility, and investment motives.

2. What Is the True Transaction Cost?

Objectively speaking, Friend.tech’s economic design and narrative are elegant—but after trying it myself, I decided to stop operating my Room because it’s fundamentally a negative-sum game with heavy leakage.

Let’s start with a question: what is the actual cost of trading a Key? Clearly, 10% is the wrong answer.

Imagine this scenario: you deposit 1.1 ETH into the system. Since buying incurs a 10% fee, you can only purchase one Key worth 1 ETH. Your Room Value now shows 1 ETH. But whenever you sell, you’ll pay another 10% fee, meaning your position’s realizable value drops to just 0.9 ETH. From the moment of purchase, the 10% exit fee is unavoidable—it’s simply deferred. In reality, you’re already down 1 - (0.9 / 1.1) = 19.2%, requiring a 22% price increase just to break even.

This 19.2% loss isn't hard to calculate, but unfortunately, it's the second layer of illusion employed by Friend.tech.

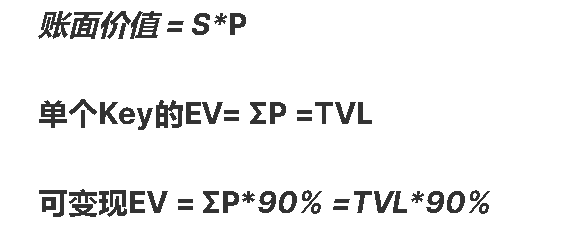

To grasp this, we must distinguish between Book Value (BV) and Expected Value (EV). Let's assume all Key buyers are speculators (we'll address other types later):

(1) Zhang San, Li Si, and Wang Wu jointly fund the purchase of a cow, a duck, and an egg. They agree the first to exit takes the cow, the second gets the duck, and the last keeps the egg.

(2) Each believes they have a claim to the cow, but in fact, their claims are equal. There are six possible exit orders, resulting in these outcomes: 1) Cow-Duck-Egg, 2) Cow-Egg-Duck, 3) Egg-Duck-Cow, 4) Egg-Cow-Duck, 5) Duck-Cow-Egg, 6) Duck-Egg-Cow.

(3) With equal probability across all scenarios, Zhang San’s true expected ownership is 2/6 × cow + 2/6 × duck + 2/6 × egg — i.e., 1/3 cow, 1/3 duck, 1/3 egg.

This example illustrates that although each person feels entitled to the cow, there’s only one cow—the perception is illusory. Their true asset value equals the mathematical expectation (EV) of their claims summed up. If a new player Zhao Liu joins and contributes a house, that house is instantly divided into four parts—Zhang San, Li Si, and Wang Wu each gain 1/4 of it.

Thus, every new entrant dilutes the EV of existing holders. This is the essence of Friend.tech:

(1) Blurring EV and book value to create wealth illusions

(2) Using the EV of later participants to generate profits for earlier ones.

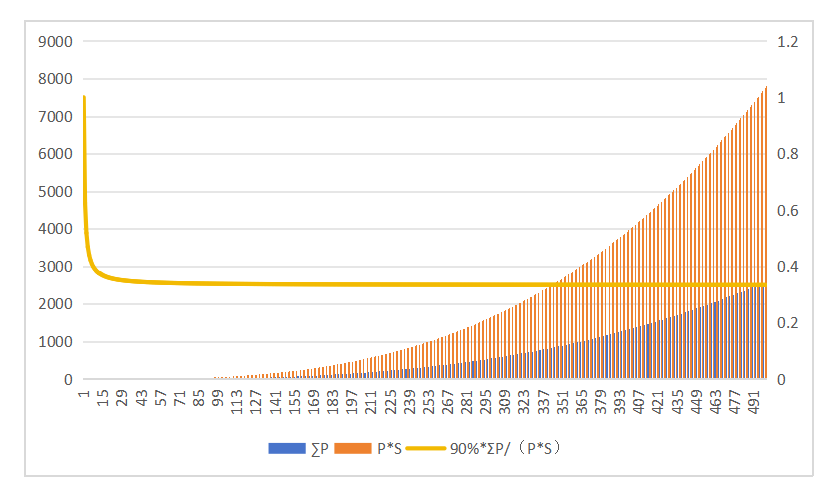

Friend.tech operates with a shared pool as the sole counterparty, meaning available trading capital is limited to the TVL within the pool—this creates divergence. For instance, when there are 40 Keys priced at 0.1 ETH each, total market cap = 40 × 0.1 = 4 ETH, whereas TVL = ΣP = 1.38 ETH. Understanding this allows us to plot the relationship between Book Value (BV) and EV (yellow折线图in the chart).

Note that once the number of Keys exceeds ~20, EV/BV stabilizes around 30%, approaching 30% asymptotically. Two implications follow:

(1) If you buy when the curve has flattened, beyond paying 10% upfront and another 10% upon sale, you immediately lose about 70% of your EV.

(2) The Room Value displayed by FT is overly optimistic. Based on prudence, valuing your Key holdings at Room Value × ~30% (EV) is more scientifically sound.

This also explains why, over the past period, seemingly everyone achieved at least 2–3x nominal returns.

3. Where Is Growth Heading?

Now consider the break-even question. Assume all users join solely for profit. If using book value as the benchmark, breaking even isn’t difficult—even buying at 5 ETH requires only 27 new buyers to recover costs.

But from an EV perspective, breaking even on high-priced Keys is nearly impossible. Buying a 1 ETH Key requires 115 new entrants to achieve EV breakeven. During growth phases, people naturally treat book value as a reliable metric, but once growth stalls or reverses, this measure becomes unreliable.

Regardless of whether measuring by BV or EV, a common issue arises: the higher the purchase price, the more new buyers required to break even. Yet growth has limits. Suppose the maximum number of users is N—then buyers from position N-M onward cannot recoup their investment. Rational players thus avoid entering after N-M. Since this information is public, no one buys between N-M and N, prompting rational actors to avoid entry after N-M-L, and so on. Eventually, equilibrium prices drift downward continuously.

In fact, this is a classic case in game theory known as the “2/3 Game.” If the logic seems unclear, refer to explanations of the “2/3 Game” or Season 2 of the Japanese drama *Alice in Borderland*, specifically the episode “King of Spades [Beauty Contest].” :)

Put bluntly, once net inflows slow, high-value Keys become unprofitable first. Speculators shift attention to lower-priced Keys. This cycle repeats, pushing down the price ceiling for individual Keys—especially new ones. Normally, such decline wouldn’t be catastrophic, but Friend.tech suffers from rampant bot activity. Bots dominate the low-price tier of new Key launches. As launch equilibrium prices fall into bot-dominated zones, users’ EV gets further eroded through arbitrage.

4. Is (3,3) Really Reliable?

The next question: Is (3,3) trustworthy? The answer is no. Reasons include:

(1) (3,3) is mostly asymmetric. For example, if you buy a 3 ETH Key while your own Key is worth 0.1 ETH, your purchase generates 0.15 ETH in fees for the seller, but they contribute only 0.005 ETH to you.

(2) The (3,3) model becomes extremely unstable with multiple participants. With only two parties matching prices, (3,3) can be stable—like warring states exchanging hostages: if you kill mine, I’ll kill yours. But with more players involved, stability collapses.

This reflects another classic game theory model—the evolutionary game. Deriving it is complex and tedious. Simply put, with enough players, someone will always find it profitable to defect early. When A defects and gains, B suffers losses and thus has stronger incentive to preemptively secure profits or minimize damage. C, D, and E begin suspecting each other. Since EV is far below BV, a chain of mutual distrust forms, leading inevitably to the sole Nash equilibrium: (-3,-3).

Note: Past periods may appear full of stable (3,3) cases, but this was merely due to rising markets where EV exploitation was easily overlooked and the tendency toward (-3) was low. Once growth halts or declines, (-3) behavior will increase significantly. This analysis applies only to multi-party (3,3) among strangers. If participants are real-life friends or have formal agreements, (3,3) can remain stable since choosing (-3) incurs additional reputational costs.

5. Is Farming Points Profitable?

First clarification: current estimates of farming yield are based on projected FDV. When formulating strategies, true EV = estimated FDV-based return × probability of actual airdrop × (1 - slippage rate) (e.g., linear vesting, lower-than-expected token price).

Based on personal experience and feedback from others, current points exhibit two key traits:

1) Most users' final points correlate almost entirely with their holdings, measured via a snapshot taken before distribution—only holdings at that moment count.

2) Earlier we noted that Key book value is roughly triple the TVL—therefore, when calculating total capital input, use TVL × 3 as the base for all users’ farming efforts.

Having understood all Friend.tech mechanisms, if you still wish to farm points, the optimal strategy is to make a single purchase and hold your alt account’s Key. This avoids EV dilution and reduces fees by 5%. However, note that even under minimal slippage—buying fully at current price and selling after six months—your total opportunity cost equals total investment × 0.905, i.e., a 9.5% principal loss. Over the following six months, refrain from any trades to avoid additional wear.

6. Where Is FT Headed?

All previous discussions assume pure speculation by all participants. But reality differs—many group leaders are already offering differentiated services through Rooms, and these genuine “services” are key to Friend.tech escaping its Ponzi nature.

Returning to the earlier example of Zhang San, Li Si, and Wang Wu pooling funds for a cow, a duck, and an egg—suppose Zhang San commits to exiting last. Then Li Si and Wang Wu’s EV changes from 1/3 cow + 1/3 duck + 1/3 egg to 1/2 cow + 1/2 duck—an obvious improvement. If Li Si also commits to leaving last, Wang Wu’s EV becomes a full cow.

The underlying principle is that utility-driven participants disrupt the homogeneity of claims, thereby increasing remaining participants’ EV. In real-world Friend.tech, this manifests in two ways:

1) Issuer self-holding, binding (3,3) agreements, and passive holders (e.g., ETFs)

2) Users with actual utility or holding needs—for example, seeking connections with issuers via Rooms, accessing alpha information, enjoying real-world perks, or benefiting from future airdrop redistributions.

A Key’s rights determine its utility value and holder loyalty, making them junior claimants. Speculative demand produces homogeneous senior claims, more sensitive to price swings and inherently less stable. Going forward, clear differentiation among Keys is inevitable—(3,3) schemes and purely speculative Keys will struggle to survive.

7. High Fees + Bots Are Killing the Game

Accounting for utility-based demand, Friend.tech has potential to transcend Ponzi dynamics. Yet last week, I sold all my Keys and stopped managing my Room, because FT’s high fees and rampant bots are destroying the ecosystem.

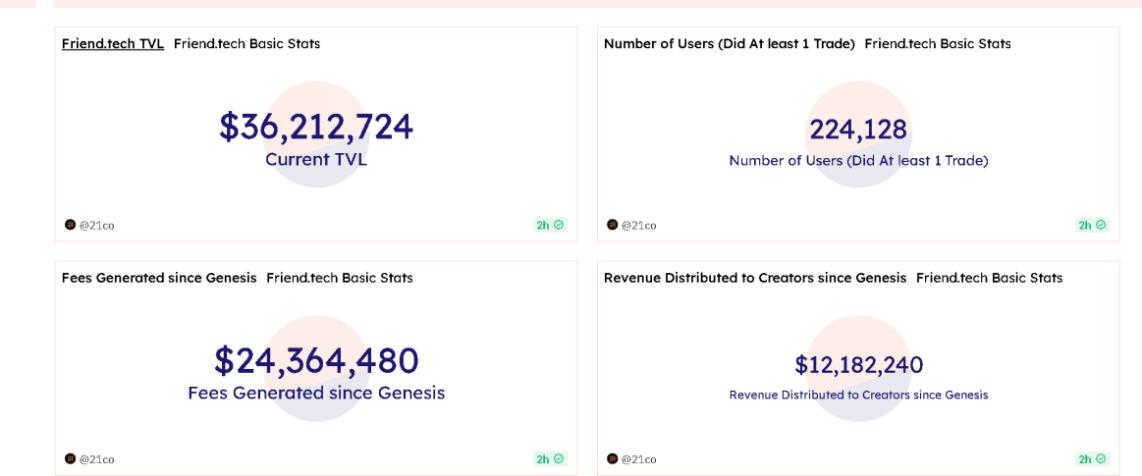

On one hand, Friend.tech charges (5% + 5%) × 2 = 20% total fees. Even OpenSea—a notoriously high-friction marketplace—charges only 2.5% royalty + 2.5% fee per side, totaling just 5% round-trip—four times less. Data shows Friend.tech currently holds ~$36M TVL, yet transaction fees have reached a staggering $24M—with $12M going directly to the protocol.

Using our earlier method, $36M TVL corresponds to ~$110M total market cap—a reasonable estimate. Even ignoring net withdrawals by users or bots, in the most friction-minimized scenario, $48M entered the system. After less than two months of trading, $12M—25%—already belongs to Friend.tech.

Additionally, when Keys are sold, another 10% fee is levied—this portion has already accrued but is deferred. Moreover, assuming $110M total Key market cap and a daily turnover rate of 5%, Friend.tech collects 5% × 30% × $110M × 10% = $16.5M monthly—about 45% of current TVL. Everyone’s net deposits flow relentlessly into Friend.tech’s coffers.

The argument that “high fees encourage holding” doesn’t hold water. Encouraging holding doesn’t require taxing buyers 10%. Recent updates—web version rollout, Watch List addition—and point rules (Room Value depends on purchases)—suggest Friend.tech isn’t genuinely promoting long-term holding. After all, who could resist such consistent, growing protocol revenue?

Finally, credit where due: Friend.tech’s product design, economic model, and operational strategy are outstanding and worthy of study. Social remains one of Web3’s most promising directions. If Friend.tech could reduce fees to a reasonable level (or reinvest most proceeds into development rather than luxury homes) and solve the bot problem, I’d gladly become one of its most loyal users.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News