DAW: Pioneering an Infinite On-Chain Gaming World

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

DAW: Pioneering an Infinite On-Chain Gaming World

DAW and its parent set "Full Chain Games" are expected to become significant components gaining attention in the blockchain field in the future.

I. Game Development Overview

DAW, or decentralized Autonomous Worlds, is a subset of fully on-chain games—games that exist entirely on the blockchain, are open-ended, and have no predefined gameplay mechanics. Before diving into DAWs and full on-chain gaming, let's first break down several key components involved in game development: game assets, game logic, game state, and data storage.

Web2 Games

In this article, we categorize Web2 games into two types: autonomous world games and non-autonomous world games. Both share a common trait: all game-related elements are stored on servers controlled by centralized game companies. Whether it’s game assets or rule configurations, everything is governed by central authorities. In these games, players generally lack true ownership over in-game items. Game companies retain control over virtual goods, characters, and progress, limiting players’ ability to freely trade, sell, or monetize their digital property.

This often leads to frustrating experiences. For example, Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin reportedly quit playing World of Warcraft after Blizzard removed his favorite character’s abilities. Similarly, when Blizzard shut down its Chinese servers in recent years, it caused significant dissatisfaction among Chinese players.

Web2 Non-Autonomous World Games

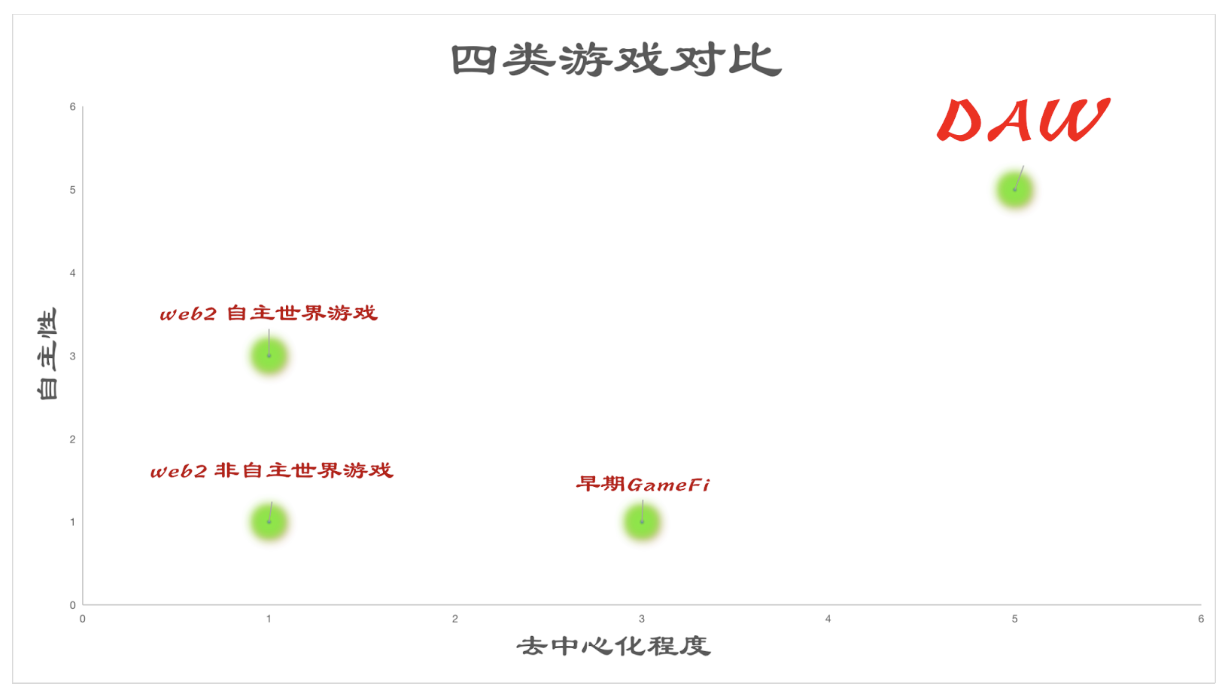

As shown in the figure above, we classify online games to date into four categories. Web2 non-autonomous world games include titles like Honor of Kings, League of Legends, and Naraka: Bladepoint. These games typically feature specific in-game objectives such as “ranks.” As illustrated, they exhibit relatively low decentralization and autonomy. Compared to autonomous world games, player creativity and game openness are limited.

Web2 Autonomous World Games (CAW)

Beyond non-autonomous world games, Web2 also includes a category of autonomous world games, as shown above. These games offer high levels of player autonomy but remain highly centralized.

Minecraft is a prime example. It’s a sandbox game where players explore, interact with, and modify a procedurally generated world composed of blocks.

The environment also includes animals, plants, and various items. Gameplay involves mining resources, battling hostile creatures, gathering materials, and crafting new blocks and tools. The open-ended nature allows players to create buildings and artworks across single-player maps or multiplayer servers.

In Minecraft, there are no fixed end goals. The game encourages creative freedom, enabling novel gameplay styles. Players can build houses, raise animals, or engage in advanced activities—such as one streamer using large quantities of TNT to produce spectacular explosions, or another constructing a functional computer complete with mini-games inside the game.

There are countless such remarkable creations in Minecraft, showcasing its immense potential.

Beyond the previously mentioned "Creative Mode," Minecraft offers various other modes: in "Survival Mode," players gather resources, build shelters, craft tools and weapons, fight enemies, and manage health and hunger; in "Adventure Mode," players explore custom maps with restricted building capabilities, following preset rules; in "Multiplayer Mode," players connect via LAN or the internet to collaborate on construction projects, engage in PvP combat, or embark on adventures together.

Additionally, players can install third-party mods to alter gameplay, add content, and enhance functionality, greatly increasing the game’s diversity.

These represent only a small fraction of what’s possible in Minecraft. Due to its high degree of freedom and extensibility, players can develop unique playstyles based on personal interests and creativity.

Web3 Games

Early GameFi

As discussed earlier, Web2 games suffer from centralization issues. Therefore, in the blockchain gaming (GameFi) space, people began exploring whether blockchain technology could enable better gameplay and economic models.

On-Chain Assets

Thus emerged GameFi—blockchain games that incentivize players economically through “play-to-earn” mechanics. Players earn cryptocurrency and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) by completing tasks, battling others, or leveling up. As shown in the diagram, compared to the two types of Web2 games mentioned above, GameFi achieves higher decentralization, though still lacks autonomy and falls short in full decentralization.

Following the emergence of GameFi, notable projects such as Axie Infinity and Stepn surfaced, tokenizing in-game assets as NFTs and creating open liquidity economies. This approach赋予s game assets financial attributes while ensuring uniqueness and immutability.

Insufficient Decentralization

However, despite assets being on-chain, core game logic and mechanics remain off-chain, resulting in partial centralization. In early GameFi, developers retained excessive control—just like in Web2—able to arbitrarily change asset properties, rules, or even devalue assets. For instance, in Stepn (a run-to-earn GameFi), developers could unilaterally adjust the value of in-game sneakers. A pair generating $100 daily might be reduced to $50 overnight. Hence, early GameFi still suffered from centralization risks.

Unbalanced Economic Models

Moreover, most early GameFi were essentially "Ponzi schemes," where early adopters profited heavily from tokens lacking intrinsic value.

Typically, players had to purchase NFTs to participate and earned GameFi tokens during gameplay. However, teams often relied solely on forcing NFT purchases for revenue, while producing unlimited tokens, causing continuous depreciation. Token prices could only be sustained by attracting new players to buy more NFTs.

Once revenue from new NFT sales dropped below the team’s token buyback costs, price stability collapsed. Early players would then begin dumping tokens, triggering panic selling and a downward spiral.

Web3 Autonomous World Games (DAW)

Hence, questions arose: if assets can go on-chain, why not move all game logic and data storage onto the blockchain too? This led to the concept of full on-chain games—games where not just assets, but every aspect including logic, state, and data, resides entirely on the blockchain, ensuring complete decentralization and chain-based operation.

DAW is exactly such a type of full on-chain game—but its significance goes further. A DAW is an “infinite game” without predefined goals or opponents. It establishes only minimal foundational rules based on a “digital physical reality” as constraints. By offering publicly accessible programmable interfaces, players are empowered to freely create, enhance, and expand experiences within this digital realm, thereby evolving the game narrative itself.

Note: “Digital physical reality” refers to a system of fundamental laws existing in computational worlds. Each world contains its own set of basic principles governing all events within it—these are the physics of that world. Note that this does not refer narrowly to physical laws in our atomic world, but broadly to any foundational rule system within any “world.”

As a subset of full on-chain games, DAWs go beyond others by storing not only assets and game logic on-chain, but also exhibiting stronger autonomy, richer gameplay, and greater playability. As shown in the figure, DAWs significantly outperform the other three game types in both autonomy and decentralization.

So, what makes DAWs stand out?

Full Decentralization:

As fully on-chain games, DAWs are immune to operator shutdowns. Even if the company behind the game dissolves, players can continue playing.

In contrast, centralized games like Minecraft face major disruptions if operators discontinue service or shut down servers.

Furthermore, unlike early GameFi where only assets were on-chain, DAW stores all game elements on-chain, making it more secure and strengthening player ownership.

Greater Autonomy:

DAWs emphasize player agency. Beyond sharing the “autonomous world” characteristic with CAWs, DAWs allow players to develop plugins for others—like creating virtual marketplaces. They can also undertake activities difficult or impossible in CAWs, such as forming a “world government” and enacting self-defined regulations.

Economic Incentives:

As blockchain games, DAWs can issue tokens and NFTs. Players may receive economic rewards—for example, via airdrops—or pursue incentive-driven objectives encouraging participation in various activities.

Take OP Craft (discussed later) as an example: the game encourages players to design mini-games within the world. They can apply for sponsorship from the OP Craft Foundation to attract more participants. Upon successful completion, players receive corresponding rewards. This mechanism stimulates creativity and engagement while fostering community collaboration—potentially realizing genuine “play-to-earn” dynamics.

Composability:

As full on-chain games, DAWs possess strong composability. Theoretically, different on-chain games could interoperate, enabling a metaverse ecosystem. Imagine a bold scenario: a spaceship owned in Dark Forest could be used in OP Craft, visible to others as the player pilots it through the world.

Note: Dark Forest is a decentralized real-time strategy (RTS) game built on Ethereum, inspired by Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem series—specifically the “Dark Forest” thought experiment. It’s an MMO space conquest game where players discover and colonize planets in an infinite, procedurally generated, cryptographically hidden universe.

While no current project fully realizes this vision, such theoretical possibilities are conceptually feasible. Various initiatives are actively working toward making them real. As the ecosystem grows and collaboration strengthens, these ideas may soon become tangible.

Additionally, as GameFi platforms, DAWs can integrate with DeFi. Players can stake tokens in yield farms, or even re-stake trading pairs in other DeFi protocols for secondary yields. Such DeFi “nesting” strategies significantly enrich the DAW experience.

II. How DAWs Are Built

Having discussed DAWs’ competitive advantages, how are they actually implemented?

Decentralization shifts power from traditional developers to players as creative agents. Composability breaks down walled gardens, and true ownership becomes possible.

Yet in early GameFi, we didn’t see the promised decentralization and composability—players lacked autonomy and meaningful involvement in content creation, and game projects failed to genuinely share blockchain states.

Core Challenges

To truly realize DAWs, several core problems must be solved:

1. Lack of Game Development Frameworks: Most teams build independently, leading to inefficiency and missed opportunities to reuse shared knowledge and optimize solutions.

2. Low Code Reusability: In many current blockchain games, very little code can be reused across different games. Without clear distinctions between layers and components, building next-gen games from similar codebases remains challenging.

3. Poor Data Composability: Sharing blockchain states between games and effectively leveraging data from Game A and Game B remains an unsolved challenge.

Therefore, building a true DAW requires going deeper—addressing not just “how to build a game,” but “how to create a universal, blockchain-native game development framework or engine.”

What Is a Game Engine?

A game engine is essentially a modularized library of code and tools. Developers use its APIs to handle graphics rendering, physics simulation, networking, etc., without dealing with low-level programming. This saves time and lets creators focus on game design and content. In commercial engines, Unity and Unreal are most common.

Currently, many Web2 games—and even some so-called “light-on-chain” games—still rely on Unreal or Unity. But as full on-chain games mature, some Web3 studios are developing their own engines tailored for complex decentralized logic and interactions.

Though conceptually similar to traditional engines—both aim to simplify development—the implementation differs fundamentally due to blockchain-specific requirements. On-chain engines prioritize state synchronization, security, gas efficiency, and maximizing composability and interoperability. This allows developers to focus on gameplay rather than compatibility issues, reducing the learning curve for Solidity.

Which Full On-Chain Engines Exist—Focus on MUD

Among full on-chain games, four main engines currently lead: MUD, Dojo Engine, World Engine, and Keystone. Among them, MUD and Dojo Engine stand out. This article focuses on MUD—the pioneering full on-chain game engine.

MUD is the earliest innovator in full on-chain game engines—a framework for building EVM-compatible applications. Centered around the ECS architecture, it tackles three core challenges in on-chain game development: contract-client state sync, persistent content updates, and cross-contract interoperability. By providing libraries and tools, MUD simplifies dApp development—especially complex ones like games. While theoretically usable for any app, its features make it particularly suited as an on-chain game engine.

Development Team Background

MUD is developed by Lattice, a key sub-project under 0xPARC. 0xPARC was originally co-founded by the team behind Dark Forest—the first fully on-chain game—alongside several other projects.

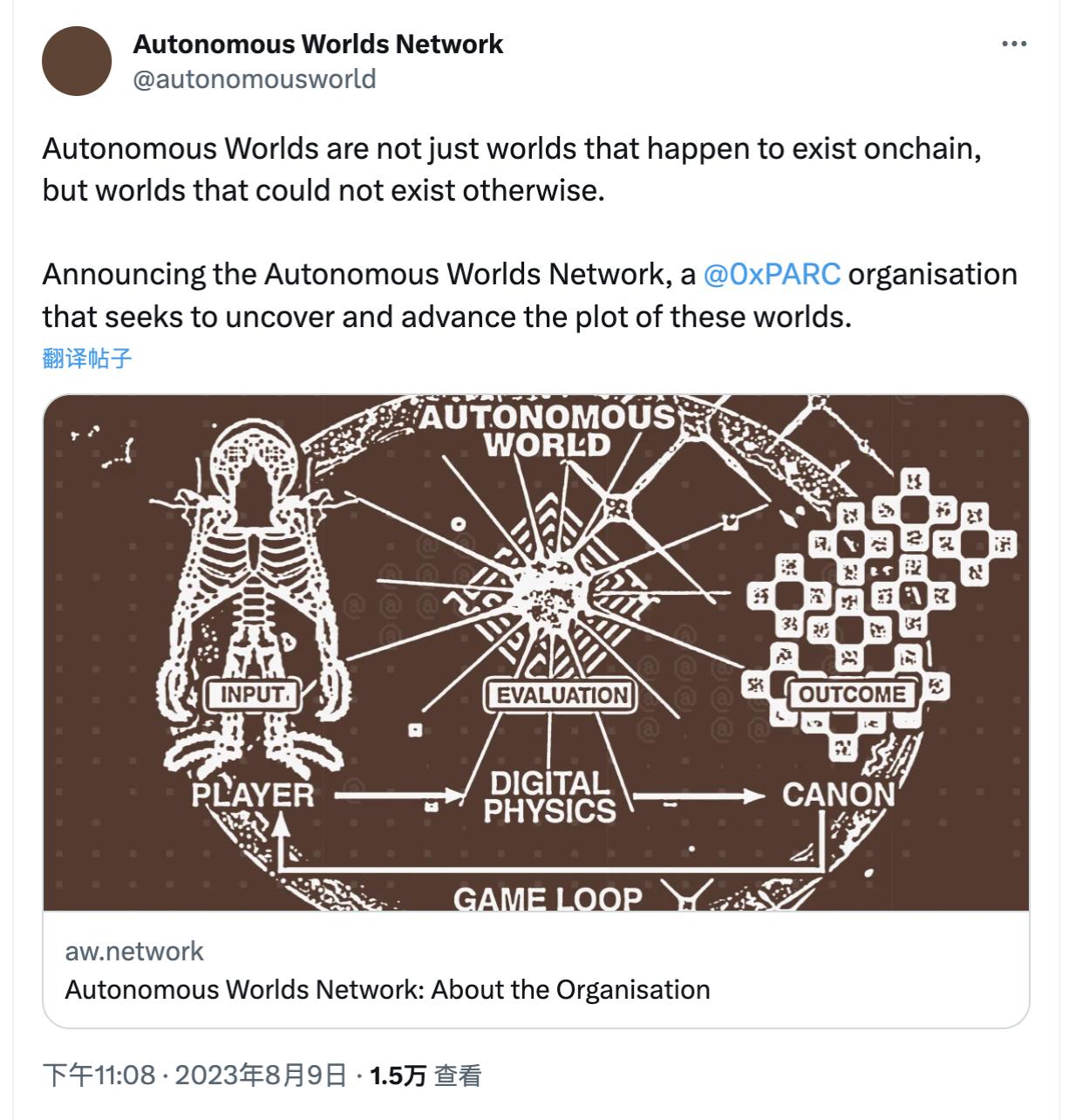

Notably, 0xPARC introduced the concept of “autonomous worlds.” From mid-September to mid-December 2022, it hosted an “Autonomous Worlds Residency” event, bringing together teams like Lattice, Dark Forest, DFDAO, CAPSULE, and Moving Castle to foster collaboration, idea exchange, learning, feedback, and shape this emerging field.

During the residency, 0xPARC provided financial support: £600/$720 monthly for travel and £1,500/$1,800 for housing. Additional grants were available based on project scope, team size, and commitment level.

As shown above, 0xPARC recently launched the Autonomous Worlds Network. According to official announcements, the network focuses on:

1. Research & Development: Supporting experimental methods and projects pushing boundaries of autonomous worlds on and off blockchain.

2. Open-Source Tools & Infrastructure: Encouraging development of new tools and infrastructure aligned with open ecosystem values.

3. Education & Ecosystem Growth: Supporting a creative ecosystem of developers, technologists, artists, writers, and designers contributing to defining and shaping autonomous worlds.

ECS (Entity-Component-System Framework)

ECS is a classic framework in traditional game development—an architectural layer atop general engines, designed to manage relationships, interactions, and updates among game objects.

Compared to other software patterns, ECS offers multiple advantages: high efficiency by loading only necessary scene data, and great flexibility allowing easy creation of new game objects and systems.

Benefits of using ECS in game development include:

1. Efficiency: ECS excels in memory and CPU usage by loading only required data per scene.

2. Flexibility: Entities contain no inherent data or behavior—defined solely by attached components—enabling effortless creation of new objects and systems.

3. Scalability: ECS avoids centralized data structures, storing entities and components distributively—making it ideal for massive games with millions or billions of entities.

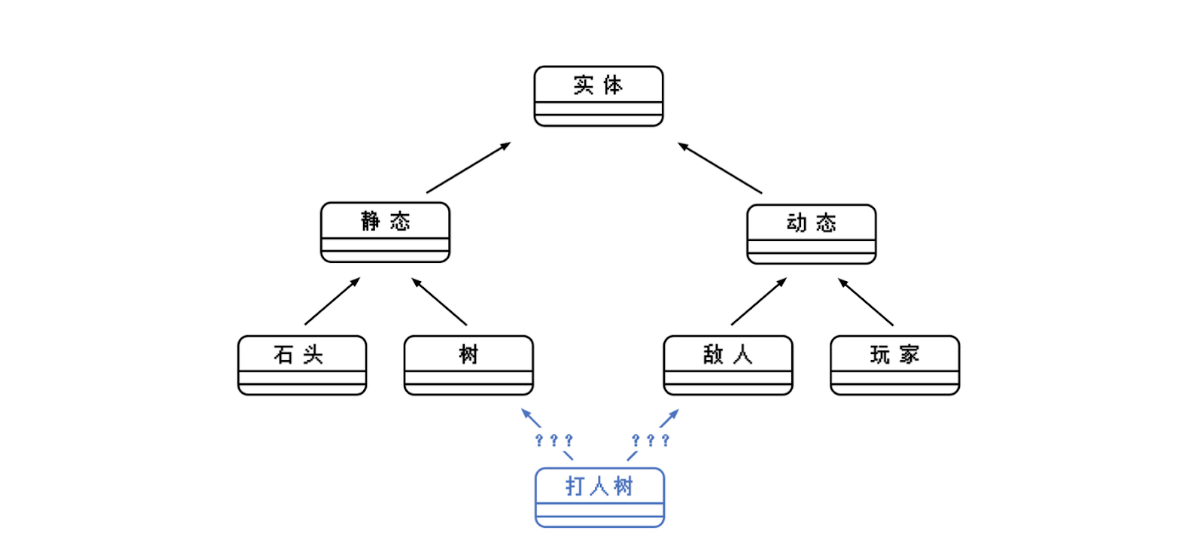

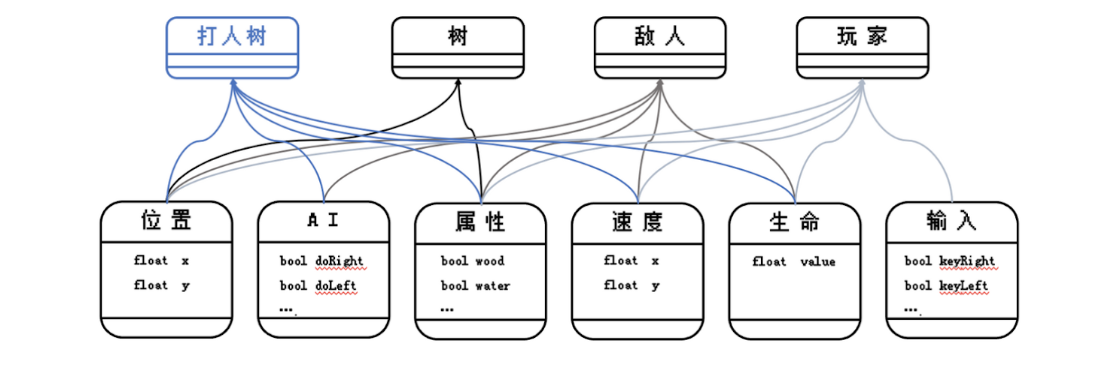

Problems with OOP

Before ECS became widespread, the industry commonly used Object-Oriented Programming (OOP), nesting game objects within class hierarchies to inherit attributes and functions.

This approach has clear drawbacks:

1. Inheritance Complexity: Relationships must be defined early—a near-impossibility. When new object types require functionalities from multiple existing classes, inheritance becomes messy and hard to maintain.

2. Maintenance Burden: As game content expands, the number of classes increases dramatically, making maintenance cumbersome.

3. Performance Bottlenecks: Many engine modules operate independently (e.g., rendering vs. networking). But stuffing all properties into one object inevitably impacts performance.

How ECS Solves These Issues

Note: This section references Fully On-Chain Games III: Engines & Ecosystem – Mud & Dojo

By adopting ECS, MUD abandons OOP, breaking all attributes into standalone components—health points, position, elemental traits, etc.

In ECS, an entity is merely a unique identifier for a collection of components. So a “player” corresponds to a component set like {“HP”, “MP”, ...}. Crucially, neither entities nor components contain logic—all computation is handled by systems. For example, a movement system manages entity motion, while a damage system calculates combat outcomes.

To illustrate, consider a simple game with stones, trees, enemies, and players. Traditional OOP implementation looks like this:

With ECS, it becomes:

Clearly, ECS is a highly modular data management system. Its “entity” concept revolutionizes game design—no longer requiring constant programmer intervention for logic changes. Entity relationships are also easier to adjust post-launch.

Ownerless Spaces

One standout feature of MUD is enabling anyone to create new ownerless spaces for state and logic. Component creators can seamlessly collaborate, efficiently querying data from the central World contract without needing full node sync. Furthermore, MUD’s native interoperability enables different worlds to interact, unlocking exciting, permissionless possibilities.

Core Components

As the Web3 ecosystem matures, new approaches to app development and scalability emerge. While much attention focuses on zero-knowledge (ZK) tech and modular/data availability blockchains, MUD presents a compelling alternative.

For developers interested in MUD, the framework provides several core components: Store, World, Foundry, and MODE.

Store acts as a gas-efficient, SQLite-inspired on-chain database, giving developers table-, column-, and row-based data storage and retrieval—offering a more manageable alternative to standard Solidity storage. With Store, devs can define custom data structures (e.g., AllowanceTable) and interact via set/get operations.

World serves as the kernel entry point, providing standardized access control, upgradeability, and modularity. It mediates between contracts and storage, ensuring secure, controlled data access. Systems themselves are stateless contracts executing world logic and reading/writing to storage. Using custom permissions, MUD promotes modular, upgradable designs across contracts.

Beyond Store and World, MUD offers ultra-fast Foundry-based dev tools (client-side data mirroring chain state) and MODE—a Postgres DB mapping one-to-one with on-chain state. MODE enables SQL queries on chain data and efficient materialized views for real-time client syncing.

By leveraging MUD’s Store and World, developers can build on-chain apps without extra indexers or subgraphs. On-chain data becomes self-managed, with changes propagated via standard events. MODE plays a crucial role in syncing chain state with clients in real time, eliminating complex polling or subgraph subscriptions—streamlining development and boosting overall efficiency.

With MUD, developers harness Ethereum and other EVM chains to build complex apps and games. The framework lays a solid foundation for interoperable, decentralized, and centrally unmanaged worlds. Devs can freely design custom components and systems, making it a flexible, scalable platform.

MUD’s potential applications are vast—from decentralized games and virtual worlds to DeFi and social platforms. Its modular design and multi-chain compatibility suit diverse project needs.

In sum, one of MUD’s key strengths lies in solving scalability. By leveraging off-chain solutions like MODE and efficient data sync mechanisms, MUD enables high-performance apps without compromising on-chain security—critical for handling massive user loads and transactions.

III. Examples of DAW Games

MUD-Based Games

OP Craft: The Most Representative DAW Game

Note: This section references OP Craft Official Article

OPCraft is a fully on-chain 3D Minecraft-themed game created in October 2022 by Lattice, the team behind Dark Forest. It stands as the most representative example of a DAW to date.

In OPCraft, simple rules apply: players can only perform four actions—break blocks, craft blocks, place blocks, and claim a 16x16 plot (by becoming the highest diamond staker). Additionally, players can customize the frontend using the official plugin system and deploy custom components and systems.

Surprisingly, within just two weeks of launch, this simple game exceeded expectations. It achieved massive success—not only amassing over 1,500 players and 3.5 million on-chain records—but also sparking user-generated pixel art, custom plugins, spontaneous competitions, strategic behaviors, community governance, and both malicious and cooperative player interactions.

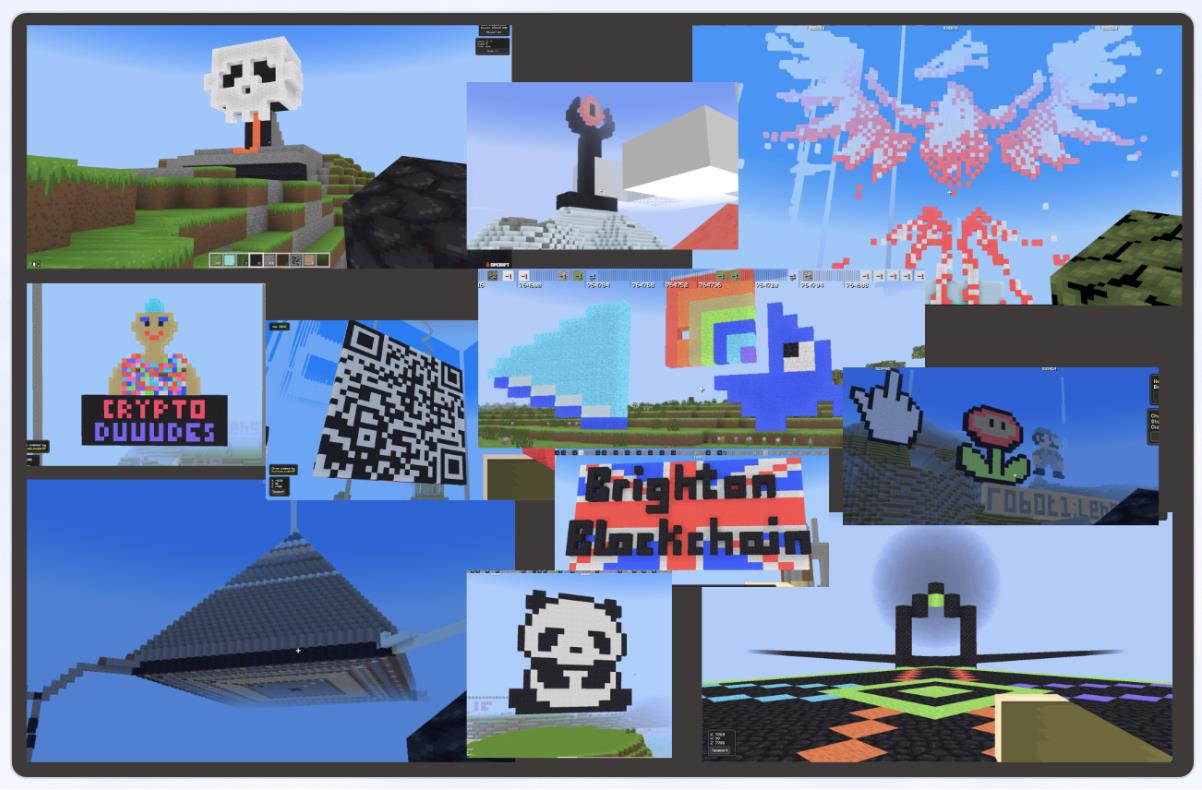

Unlocking Creativity for Artists, Architects, and Developers

OPCraft unleashed artistic and architectural talents. From humble wooden huts and towers, players progressed to intricate builds—Mario and Fire Flower sculptures, and colossal phoenix statues spanning hundreds of blocks.

Meanwhile, engineers and “scientists” leveraged coding skills to push OPCraft’s limits. Using the accessible, permissionless World1 plugin system and component framework, players explored technical frontiers—releasing auto-resource-gathering plugins (coordinate-agnostic), automated diamond drills, and chat communication tools.

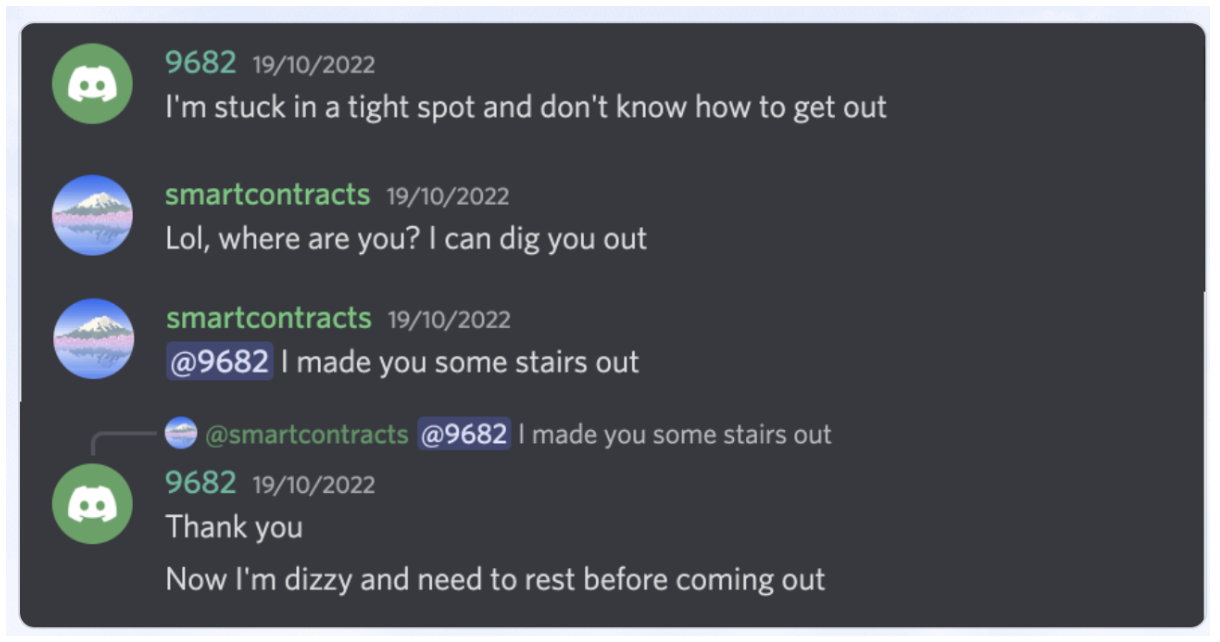

Digging and Filling Holes

Driven by mischief or collective strategy, some players dug deep pits, trapping unwary explorers.

But a positive shift followed: when someone fell in, others initiated rescue missions—filling holes or placing staircases inside. Some even developed teleportation plugins to avoid traps altogether.

A trapped player requesting help on Discord

Evolution: Tooling and Productivity Gains

Initially, players performed basic actions: picking flowers, chopping trees, mining ores, digging caves, building crude huts, and erecting narrow towers. They also created rough, barely recognizable digital shapes.

Over time, players mastered the world, learning to craft complex items like glass, dyed wool, and bricks. These advanced materials enabled larger, more elaborate artworks and constructions—showcasing composability in action.

As shown below, players used colored wool to create massive pixel art—Union Jack flags, giant pandas, and even promotional displays for their own NFT projects. Others constructed majestic sky pyramids using sand, stone, wood, and bedrock. One ambitious creation paid homage to Dark Forest—a massive planet built from 6,360 bedrock blocks.

Examples of player-built structures

Republic of SupremeLeaderOP

An interesting event occurred in OPCraft: on October 29, two days before testing ended, a player named SupremeLeaderOP announced the formation of a world government on Discord and Twitter.

This player mined a massive amount of diamonds (reportedly 135,200) and claimed numerous plots (which blocked others from building or farming without permission).

He then declared a world government in-game and released the apro-comrade plugin, allowing others to swear allegiance and become citizens. Citizenship required surrendering all private inventory, but granted access to the government treasury. Citizens could mine materials for the treasury via smart contracts deployed by the Supreme Leader and build on government-owned land using treasury supplies.

The Republic even established a “social credit” system to prevent freeloaders from taking more than they contributed. Citizens with insufficient credit had to work to “repair” their standing before regaining treasury access.

Many players voluntarily welcomed him as Supreme Leader, even building statues in his honor. Others strongly opposed him, condemning his collectivist policies and calling for resistance and freedom.

Exceptional Playability

Within just two weeks, OPCraft saw the emergence of rich social dynamics: players setting traps for fun, others collaborating to escape or fill them in.

We witnessed unprecedented speed and freedom in plugin development—unauthorized yet encouraged. We even saw new governments rise and voluntary adoption of novel rules and institutions never imagined by the developers.

In DAWs, infinite possibilities unfold—evolution occurs beyond anyone’s control. This freedom spawns deeply engaging gameplay. Compared to early “play-to-earn” GameFi, DAWs take a major leap in playability—sometimes even surpassing Web2 games in entertainment value.

Dojo-Based Games

Loot Realms Series

The Loot Realms series is developed by BibliothecaDAO. Notably, due to its community-driven nature, BibliothecaDAO did not conduct institutional fundraising. Instead, it launched its ecosystem governance token $LORD in December 2021 and completed a community-focused private round on February 1, 2023, following proposal BIP-7—ultimately oversubscribed by 6.35x thanks to strong community support.

Currently, the Loot Realms series includes two main games: Realms: Eternum, which opened its Alpha test version in early 2023; and LootSurvivor, the first “play-to-die” Roguelike game unveiled at ETHGlobal Lisbon in May 2023.

Realms: Eternum

Realms: Eternum is an economic and military strategy game built by Bibliotheca DAO on Starknet, leveraging L2 scalability. It blends mechanics from popular browser games like Travian and Tribal Wars with board games like Catan and Risk, incorporating economic elements.

The game features 8,000 Eternal Realms—each an independent territory managed and developed by its lord. Importantly, Eternum is an infinite game—meaning it will persist as long as Ethereum produces blocks, with in-world events determining its evolution.

However, the game is still under development, and user experience needs improvement.

Loot Survivor

Loot Survivor is a fully on-chain survival game where players devise RPG-style strategies to compete for loot, helping them survive traps and boss fights. If a player survives and ranks in the top three, every new adventurer who dies afterward pays tribute in $Lords until surpassed.

If a player dies, their $Lords and collected loot drop and become income for the level creator—an engaging mechanic that gained popularity.

However, interaction-wise, due to StarkNet’s slow and unstable network, each game interaction takes 3–5 minutes. To reach top 50 in Loot Survivor requires at least 3–5 hours. Developers reported spending about 6 hours to enter the top three—time that may far exceed six hours given current participant numbers.

Isaac is a large-scale cooperative game inspired by Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem. All players live on a planet in a trinary star system, where collision with a sun poses a high extinction risk.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News