When All Apps Look Like Protocols: The Rise of Prototype Apps in Web3

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

When All Apps Look Like Protocols: The Rise of Prototype Apps in Web3

The next great social apps will all look like protocols.

Written by: DAVID PHELPS

Translated by: TechFlow

I.

Two questions haunt those bold enough to build consumer applications:

-

When all evidence points toward protocols, do we really believe apps can accumulate value? In a world where protocols like Ethereum easily generate fees, justify tokens on secure base layers, and capture value from everything built atop them, can apps truly make money?

-

Given that apps overall increasingly resemble the historical phenomenon of 2008–2012, can new apps even establish sustainable user bases? After all, why hasn’t any broadly adopted, enduring new app emerged in nearly a decade—or if we exclude TikTok, in over a decade?

The obvious answer to both questions is so grim that once our investors reach the understandable conclusion that apps cannot accumulate value, investment in apps will inevitably decline, and hope for rebuttal will be slim.

Let’s give the other side its due: some investors might ask whether this pessimism signals that apps have bottomed out. Perhaps one app narrative has ended, and another will rise? Of course, this assumes that the app cycle is indeed cyclical, rather than merely a fleeting moment during the Web2 decade of the 2010s.

Yet while such investors may diligently marshal evidence for a new app thesis, they’re likely only able to do so by making a stronger case for protocols. Yes, our investor might cite examples like Friend.Tech, which at its peak generated about $1 million in sales; today, that figure is near $16,000—a nearly 99% drop in two weeks. Similarly, they might argue that Friend.Tech’s fees exceed those of the Base protocol it’s built upon; but if the app truly heralds more to come, then Base will inevitably earn more in aggregate from its suite of apps than any single app earns alone.

The argument seems clear: even the strongest case for apps ultimately accrues to the protocol layer.

Joel Monegro wrote “Fat Protocols” in 2016, at the height of the app era, observing that “the market cap of protocols always grows faster than the value of applications built on top, because success at the application layer drives further speculation at the protocol layer.” Many have tried to refute Fat Protocols—including myself—but by 2023, it appears self-evident.

Indeed, Fat Protocols offer an elegant answer to both questions: the reason no great new apps have emerged over the past decade is precisely because value has begun concentrating at the protocol layer.

Rather than trying to prove apps can somehow become better investments or revenue generators than protocols, let’s instead address the real answers to our two key questions: Can apps today capture value? Can apps today acquire sustainable users?

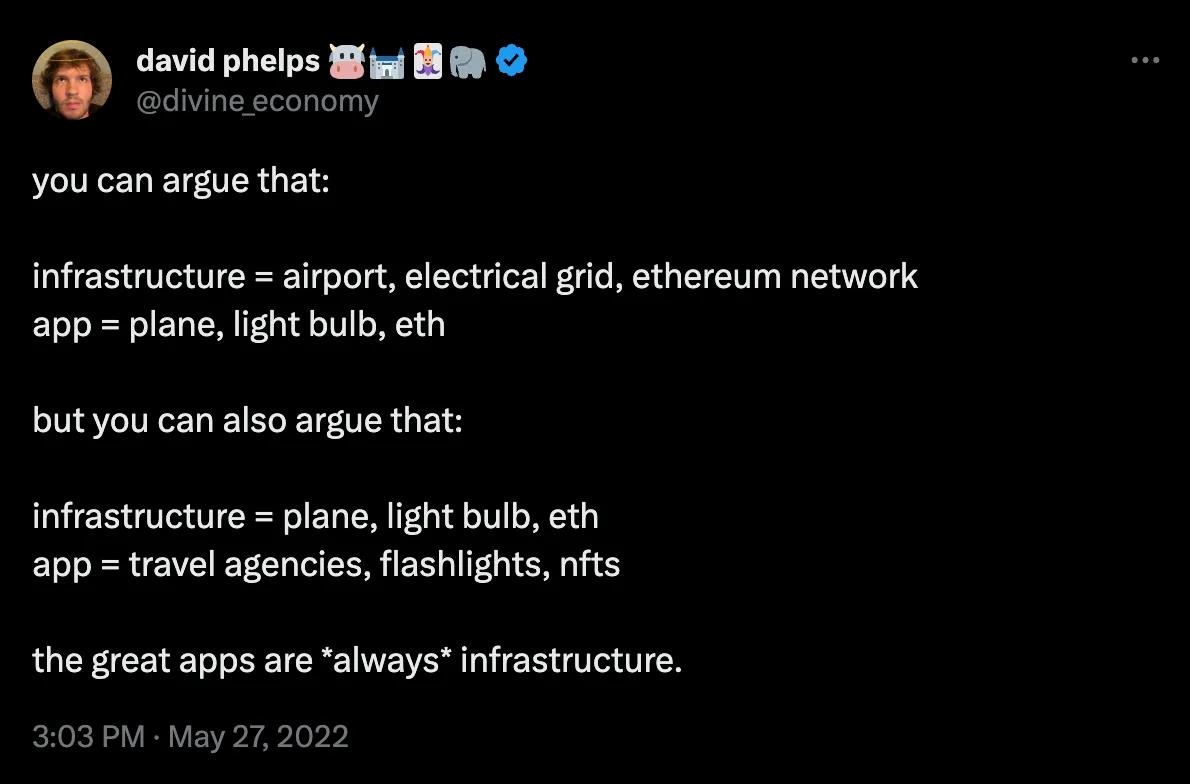

Even asking whether value accumulates to apps or infrastructure assumes they are mutually exclusive categories. And asking why we lack major new apps overlooks the fact that we already have them—they just don’t look like traditional apps.

So why aren’t they?

Because the next wave of great social apps will all look like protocols: proto-apps.

II.

Why haven’t we seen any broadly adopted, enduring apps since TikTok—only sporadic novelties that fade with time? This can be attributed to what we might call the Social App Thesis, which determined the fate of dominant apps over the past decade: social apps. In short, the categories within social are limited, and the winner in each category gained strong enough distributed network effects to fend off competitors.

In other words, our app stores are full. We’ve exhausted the five primary modes of online expression:

-

Long video (YouTube);

-

Short video (TikTok);

-

Long text (Reddit);

-

Short text (Twitter);

-

Images (Instagram).

In the early days of social apps, you could succeed by combining these categories—like Tumblr or Facebook, which merged images, short text, long text, and video. But that was only a temporary opportunity before social apps became fully decomposed.

In fact, over the past five years, the only path to launching a successful new app was creating an entirely new category—such as real-time audio (Clubhouse) or real-time photos (BeReal). While these experiences were novel, they hindered sustained interaction, which is foundational to successful social dynamics.

In other words, there are no categories left, and no way to compete within the ones now dominating daily life. You could build a competitor ten times better than Twitter: yet Twitter remains where publishers reach the widest audience and readers engage most directly with creators. They can’t get that elsewhere without spending years rebuilding their social graph. Every second spent doing that—away from Twitter—is a second readers and writers spend so much time consuming each other’s attention that they have little left to seek elsewhere.

Distributed network effects (or their absence) also explain why only two main app categories allow newcomers to share market share without fully disrupting incumbents: messaging and dating.

Messaging and dating apps arguably follow the same pattern. Since they aren’t public markets between creators and audiences, their network effects are weaker. Simply put, users don’t rely on messaging or dating apps to reach the broadest possible audience of strangers, so switching apps to contact different groups doesn’t cost them much. But note: the leading players here are also a decade old—Signal (2014), Telegram (2013), Discord (2012), Snapchat (2011), WhatsApp (2009); Bumble (2014), Tinder (2012), Hinge (2011), and so on.

Even with weaker network effects, the space remains too crowded for newcomers. As Chris Paik said in 2021: “The reason we aren’t seeing new mobile-first social companies emerge is because we’ve entered the smartphone half-life phase.”

According to the Social App Thesis, we’ve reached a state of saturated maturity.

It’s hard to say the Social App Thesis is wrong—within its own frame, it seems irrefutable. Yet curiously, it ignores the fact that, after nearly a decade, a significant new app has finally risen. It’s just so different that you might not have realized it was an app at all. I’m referring, of course, to ChatGPT.

To be sure, calling ChatGPT a social app at all feels like a stretch. Sure, you could make the case. You might argue that ChatGPT, like other major social apps, is just another way to sustain endless conversations across topics of interest. The difference is that what you produce isn’t meant for public view, but for yourself—with good reason: you’re essentially chatting with an elevated version of yourself, one that has all the answers.

But even if we don’t classify ChatGPT as a social app, that tells us something: we take for granted that major apps must be social apps, and that the rules of user-generated content and messaging define the rules for all major apps.

So bear with me. The uniqueness of ChatGPT as a new kind of social app isn’t about whether we categorize it as social. You can call it a new type of social app or not—it doesn’t matter for my point, which is that we need a new model to define what successful future apps will look like. So let’s go further:

ChatGPT is the first significant app in a decade because it’s the first example of a completely new category: proto-apps.

To understand proto-apps, we must first grasp how ChatGPT breaks every rule that defined successful apps of the past decade.

III.

We can say that, at its algorithmic core, ChatGPT breaks the traditional paradigm of successful apps in three ways:

-

It launched as a web app. Although ChatGPT recently released the inevitable mobile app, unlike nearly every other major app in the past 15 years, it debuted as a web application. And for good reason: by design, ChatGPT requires only a web1-style experience—a query bar and a response window. For ChatGPT, the building blocks of web2 social—navigation bars, search, feeds—have magically vanished. That’s why we hardly need a ChatGPT app, just as we don’t need a Google app; embedding it in the browser makes more sense.

More practically, ChatGPT is a web app because launching a mobile app first would have been a bad idea. Despite conventional wisdom that major apps must be mobile apps, downloading an app is increasingly a friction point reserved only for the most popular services. Moreover, while mobile apps offer push notifications, data collection, and integration with device assistants, they come with a 30% app store commission. As I argued in “Apple Is a Country,” Apple’s vertical control over the app store, OS, and phone grants it taxing sovereignty—but Progressive Web Apps (PWAs) mark the first crack in this fortress, enabling apps to reduce fees while still supporting notifications and data collection.

Of course, a glance at the history of crypto apps over the past five years shows that web apps have worked well for them too.

-

It’s horizontal. Since the so-called unbundling of Craigslist, consensus has held that vertically tailored apps—built for specific industries and user cases—win. Last fall, when we launched a competition platform usable for hackathons, grants, bounties, prediction games, giveaways, governance, etc., my co-founder and I repeatedly faced a common concern from VCs: we should pick one use case and customize for it. While we might argue that horizontal services (e.g., Thumbtack or LinkedIn) often win through distribution moats, economies of scale, and broader user bases, VCs have a point. Even Thumbtack or LinkedIn are relatively vertical compared to Craigslist: while user profiles differ (many professions), their use cases are largely the same (finding work).

Over the past decade, people have used nearly every major app for professional networking, casual chatter, or—like Twitter—for both simultaneously.

By contrast, ChatGPT feels like a return to the web1 vision of Craigslist-Amazon “stores.” With no fixed use case, you can do anything inside its interface—learn facts, plan your day, create content, get feedback, or simply have a thoughtful conversation partner listen to your troubles. Part of the proto-app argument isn’t just that app and protocol layers are merging; more simply, it’s that these apps are proto-apps—a return to the early web.

But unlike Amazon, which evolved step-by-step from a highly specific use case (books) into a “store,” ChatGPT starts as “everything” because it delivers infinitely abundant digital bits, not finite physical goods. The more it can do, the more reason you have to return—because ChatGPT’s greatest breakthrough may be that it doesn’t force you to define your use case upfront. As AI, it responds case-by-case to your thinking, so you no longer need to determine why you’re there, as you did in web1 (choosing the right Craigslist or Yahoo category link) or web2 (opening the right app).

Horizontalization of web services no longer means forcing disparate functions into one UI, as in the Craigslist era. Instead, it looks like a strategy to capture every possible use case through user intent and language in a conversational interface.

-

It’s just a front-end to a protocol—and can integrate other services into its own front end. This is why ChatGPT can be horizontal despite a decade of verticalization. Unlike traditional apps that tightly couple front-end and back-end, ChatGPT is essentially one of many front-ends atop OpenAI’s models. You can add other front-ends to this engine: DALL·E is just a front-end for image generation, while ChatGPT is a front-end for interactive text generation.

Decoupling backend protocols from front-end apps means:

1) An app is merely a limited, user-friendly interface—a window into a much broader world; and

2) In theory, anyone can build additional front-end apps atop the same protocol.

Certainly, OpenAI powers many consumer apps. But OpenAI’s strategic masterstroke lies in enabling services to build atop its protocol—through ChatGPT’s own front end. “Plugins” let users connect to OpenTable, Expedia, Instacart, Zapier, Wolfram, and more, allowing grocery orders, travel bookings, and (eventually) market trades—all via ChatGPT. Ultimately, it could become not just a front-end to OpenAI’s models, but to any web service. A few lines of natural language, and you execute commands across the internet. Unlike the siloed data model of web2, this is built on composability—where one service can interoperate with any other on the internet.

I said ChatGPT is just a front-end to a protocol. But that also means anyone can build services atop that protocol through the app—and conversely, ChatGPT can become the front-end to any service using that protocol. More broadly: ChatGPT can become the front-end to any transaction on the internet.

As a protocol-app, its power lies not just in what can be built atop it, but in its ability to build atop others. It’s a gateway to the internet.

IV.

Looking at recent apps like Beam Wallet by Eco or Friend.Tech, we see the proto-app thesis playing out beyond AI. They are web apps—or more precisely, Progressive Web Apps (PWAs)—bypassing Apple’s app store tax collectors. They are front-ends to protocol-based smart contracts: blockchains. The real question is whether they’ll allow others to build services (raffles, giveaways, community access, DMs, etc.) atop them and integrate those into their front ends. Because doing so—becoming a portal to other services—is likely key to achieving horizontal reach.

I’ve tried to avoid talking about crypto, but by now it’s clear: crypto is exactly what I’ve been describing. In crypto, the base protocol is the blockchain itself—but any app built atop it can also become its own protocol, because anyone can build atop your app permissionlessly, composablely reading transaction data from your open-source smart contracts and acting on it in their own apps. I believe this is even a major advantage over centralized AI protocols, which can read and write any data in natural language but keep that data locked within their own apps, denying others free access for their own use. As my co-founder Sean puts it, blockchains are simply open APIs that let any service trigger actions on another.

This means every app is effectively a protocol, capable of charging fees on-chain via PWAs without paying app store commissions. Anyone can build services atop your app, and you can integrate services into your front end. Every crypto app can follow the same strategy that made ChatGPT so successful.

This is also why, contrary to popular belief, apps can actually make money when they merge with the protocol layer by letting others build atop them. By enabling others to profit—through hooks, funding, group purchases, collective investing, or even ads—proto-apps can safely take a cut. When their users make money, they make money too.

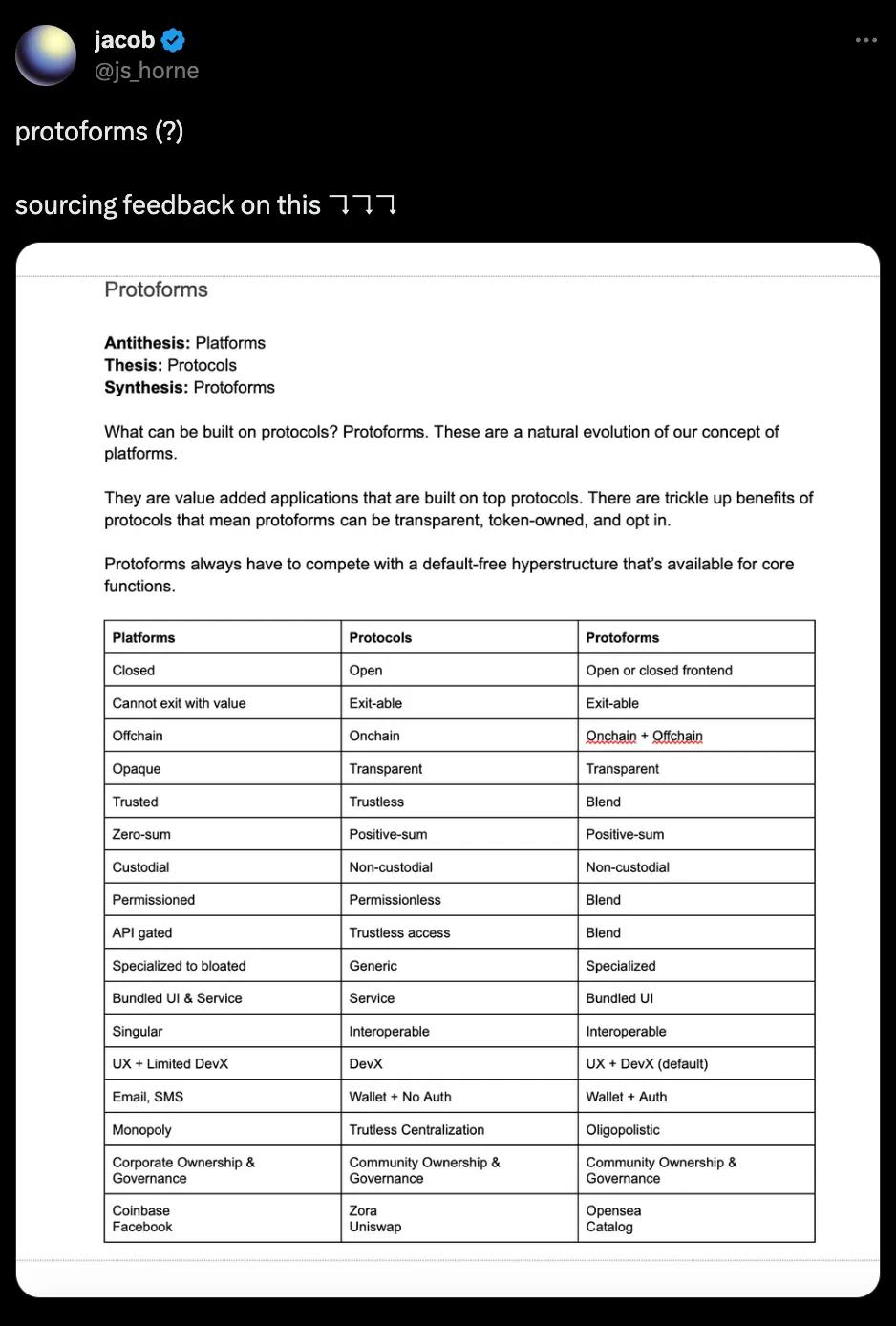

Yet because consumer spaces in both Web2 and Web3 remain deeply influenced by outdated theses that stopped working a decade ago, only a few consumer services (like Lens Protocol) actually aim to build composability as a core feature—and these remain the only true proto-apps so far.

For example, Uniswap v4 is arguably the flagship proto-app (partly because there are no other contenders). By introducing “Hooks” as on-chain APIs that let users write code to automatically manage liquidity pools, Uniswap allows anyone to build atop its app as if it were a protocol. Imagine users customizing their liquidity pools—automatically raising fees during volume spikes, paying LPs more for longer durations, or auto-sending profits to Aave for reinvestment.

These Hooks aren’t just plugins—in ChatGPT terms, they’re user-generated plugins. By letting users build Uniswap’s core product, Uniswap becomes not just a protocol, but a front-end to all its users’ desires, which can then be packaged for others. In many ways, it becomes the front-end to DeFi. Just as you might stake your $ETH via Eigenlayer to re-stake across multiple protocols, you might deposit liquidity into certain Uniswap pools that can also manage that liquidity across other DeFi services. Both Eigenlayer and Uniswap can become distribution networks to access other services. Building a proto-app means creating a gateway to every other service in the domain.

All I’m saying is that these modules can be built by almost anyone, for almost any purpose, without needing approval from an app store—that’s why web apps and horizontalization are so crucial to building apps as protocols: Proto-apps are apps that choose their own destiny, or if you prefer, frameworks for user-generated apps. They let anyone build tools to interact and transact in any way they like. If you will, they are meta-apps—apps for building apps.

Herein lies the irony. Right now, apps seem like a doomed investment class—a relic of a bygone era—yet we stand at the edge of a world where users can develop their own apps inside the apps they love, much like Roblox. New app development is no longer constrained by the walls of existing apps; now anyone can build permissionlessly. Apps are everywhere. Which is to say: protocols are everywhere too.

But there’s logic here too. The reason no outstanding apps have emerged in the past decade is that the great apps we knew have already been claimed. Yet the great apps we don’t yet know are just beginning.

Because the next great apps won’t look or act like apps at all—they’ll look and act like protocols. Or more precisely, these proto-apps will operate as something we’ve never seen before.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News