Full-Chain Game Core Analysis: MUD Engine and World Engine

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Full-Chain Game Core Analysis: MUD Engine and World Engine

As infrastructure improves, the construction and implementation of various complex ideas will be carried out through MUD and integrated via more sophisticated Rollup solutions. A new paradigm for blockchain may begin with fully on-chain games.

Author: Solaire, YBB Capital

In the past, due to limitations imposed by blockchain's linear structure, building a practical DApp on-chain was never easy. Yet despite these constraints, pioneers have never stopped pushing forward. With the emergence of the famous constant product formula "x * y = k," Uniswap—a mere few hundred lines of code—ushered in DeFi and completely transformed the narrative of Crypto. If such simple DApps could achieve such heights through developers' ingenuity, what about more complex applications? What if entire games or social platforms were built entirely on-chain? This may have seemed like a crazy idea before, but today, with Rollups unlocking scalability, this possibility is becoming increasingly tangible.

DeFi once brought hundreds of billions of dollars in TVL to Crypto. How can even more complex DApps be realized? Could they propel Crypto to new heights once again? Perhaps early-stage fully on-chain games can provide the answer. This article will analyze fully on-chain games from four perspectives: their history, current definitions, implementation methods for creation and operation, and their significance for the future of Crypto.

The Origin and Development of Fully On-Chain Games

The history of fully on-chain games dates back nearly a decade. Mikhail Sindeyev forked Namecoin and created Huntercoin, the world’s first blockchain-based game. Launched in 2013 as an experimental prototype, Huntercoin quickly attracted a passionate online following and gained support from prominent members of bitcointalk.org. Fueled by tech enthusiasts’ love for video games, the most popular Huntercoin thread received over 380,000 views. Unfortunately, Mikhail Sindeyev suffered a stroke and passed away in February 2014, halting development of Huntercoin. The HUC token nearly collapsed by 2015. Although this first attempt at a fully on-chain game did not succeed, thankfully, the story of on-chain gaming continued.

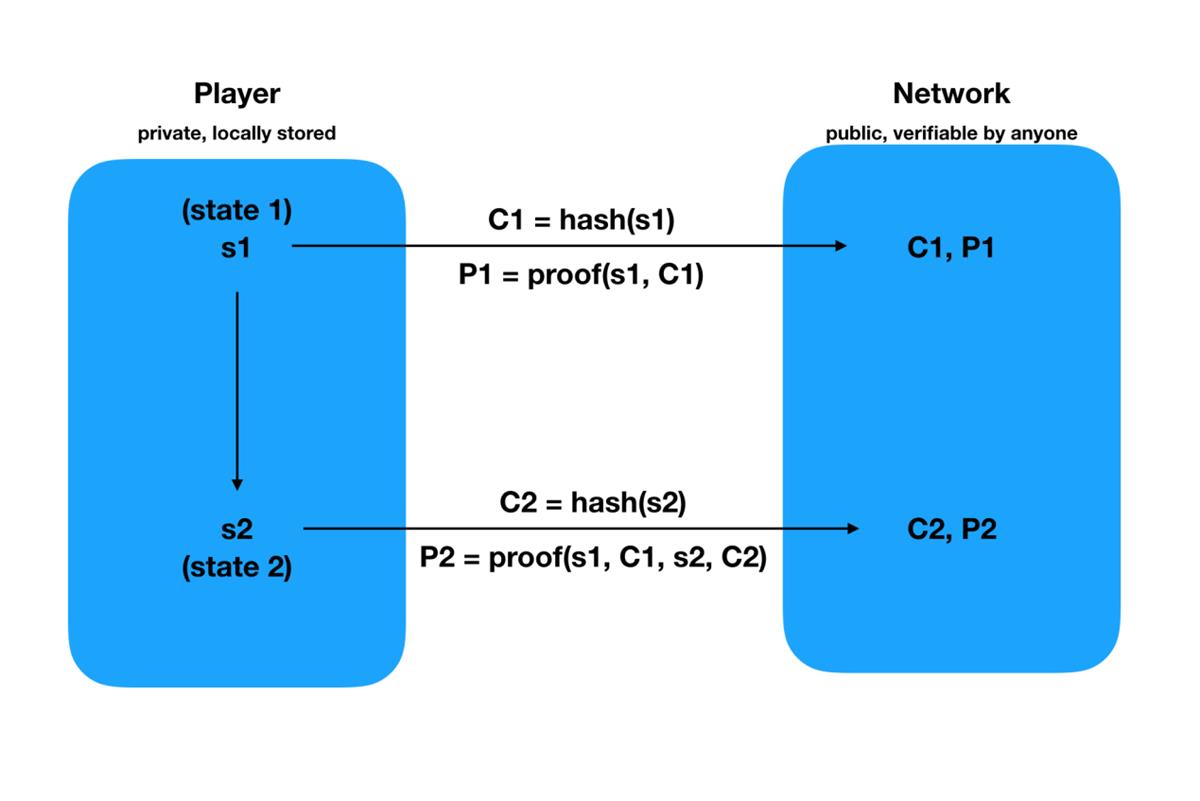

In 2020, Gubsheep (Brian Gu), Alan Luo, and SCOTT SUNARTO, inspired by the sci-fi novel The Dark Forest, developed a namesake MMORTS space conquest game called Dark Forest. Built on Ethereum, the game encoded all its rules and logic into smart contracts—making every action a transaction on-chain. At its core, the game leveraged ZK-Snarks (zero-knowledge proofs) to simulate the “dark forest” principle from the novel: once a civilization is discovered, it will inevitably be attacked.

For example, when a player wants to move from Planet A to Planet B without revealing their coordinates under the dark forest rule, they must prove the move is valid while keeping their location hidden. Since Ethereum blocks are fully transparent, Dark Forest implemented information hiding using the following method: players select their origin and destination planets—private information—and compute the hash values of both positions, which are then submitted to the blockchain. In this stage—the Commit phase—due to the one-way nature of hash functions, these hashes cannot reveal actual planetary locations. The next stage is verification—the Reveal phase—where players generate and submit a zero-knowledge proof demonstrating that their move is valid. Anyone can verify this proof without learning anything about the player’s actual planet locations.

Thus, the first fully on-chain game capable of hiding information on transparent Ethereum was born. This bold and imaginative experiment quickly caused a sensation across the entire Crypto community. Vitalik (Ethereum’s co-founder) even retweeted and praised the game on Twitter.

However, after launch, as more than 10,000 players flooded in, difficulties emerged. Ethereum’s performance proved insufficient to support such a complex application. On launch day, the game clogged the entire blockchain, consuming trillions of gas. Moreover, because the game was built using DeFi libraries and architecture, later optimizations only alleviated pain points rather than solving root issues.

Inspired by the potential of ZK-Snarks revealed in this experiment and reflecting on the challenges faced by fully on-chain games, founder Brian Gu established 0xPARC as a research institute dedicated to advancing zero-knowledge proofs. One of 0xPARC’s branches, Lattice, took charge of designing and maintaining MUD—the full-stack engine for on-chain games. Meanwhile, co-founder SCOTT SUNARTO began developing World Engine, a sharded Rollup framework specifically designed for running on-chain games.

Today, zero-knowledge proofs are widely used and well known. Our focus here will be primarily on the latter two innovations—MUD and World Engine—namely, how we create and run autonomous worlds. But first, we need to understand 0xPARC’s definition and conceptual framework for fully on-chain games.

Autonomous Worlds

Based on insights from 0xPARC’s collection of cryptographic game papers titled Autonomous Worlds, a fully on-chain game should meet at least five criteria:

-

Data originates from the blockchain: The blockchain is not just auxiliary storage, nor merely a mirror of data stored on proprietary servers. All meaningful data must be accessible on-chain—not just asset ownership records. This allows games to fully leverage programmable blockchains: transparent data storage and permissionless interoperability;

-

Logic and rules are implemented via smart contracts: For instance, battles within the game—not just ownership—are executed on-chain;

-

Game development follows open ecosystem principles: Both game contracts and accessible clients are open source. Third-party developers can fully redeploy, customize, or even fork their own experiences via plugins, third-party clients, or interoperable smart contracts. This enables game creators to harness the collective creativity of an aligned incentive community;

-

The game permanently exists on-chain: Closely related to the above points, a key test of whether a game is truly crypto-native is: if the core developer-provided client disappeared tomorrow, could the game still be played? The answer should be yes—if and only if game data storage is permissionless, game logic can be executed permissionlessly, and the community can interact directly with core smart contracts without relying on interfaces provided by the core team;

-

The game interconnects with things we value: Blockchains offer a native API for value itself—digital assets are inherently interoperable with other assets we care about. This both reflects and enhances the depth and meaning of the game, linking the game world to the “real” world.

Games built upon these standards can also be viewed as worlds grounded in blockchain infrastructure—what we call Autonomous Worlds.

What defines a “world”? A world doesn’t necessarily refer to physical reality—it can manifest in novels, films, games, poetry, or even legal systems. However, each of these worlds is shaped by central authorities (authors, developers, or groups) who define frameworks and rules before delivering them to us. The degree of autonomy varies greatly among such worlds. Take the highly acclaimed open-world game Minecraft, where players enjoy immense freedom—by placing different blocks and modifying rules, they can build entirely unique worlds. In contrast, lower-autonomy worlds like **Harry·Potter** present magical universes strictly bound by JK Rowling’s predefined rules and structures.

If blockchain serves as the foundation of a world, it unambiguously preserves the set of all entities within its state. Furthermore, it formally codifies governance rules in computer code. A blockchain-based world enables its inhabitants to participate in consensus. It operates a computer network that reaches agreement whenever new entities are introduced.

From a worldview perspective, two key blockchain concepts must be defined:

-

Blockchain State Root: The state root is a compressed representation of all entities in the world. Possessing the state root allows one to verify whether any entity is genuine. Trusting a world’s state root equates to trusting the world itself. For example, 0x411842e02a67ab1ab6d3722949263f06bca-20c62e03a99812bcd15dce6daf26e is the state root of Ethereum—the blockchain-based world—at 07:30:10 PM UTC on July 21, 2022. Calculating this root considers every single entity within the Ethereum world, representing everything contained in that world at that precise moment;

-

Blockchain State Transition Function: Every blockchain defines a state transition function—an explicit rulebook for introducing new virtual entities based on inputs from humans and machines. In Bitcoin’s case, this function dictates how balances are consumed and transferred between addresses.

Therefore, viewing fully on-chain games as worlds built atop blockchain implies a decentralized world with near-infinite autonomy—what we call an Autonomous World.

The Challenge of Creation

During early explorations into new designs for on-chain games, developers frequently encountered limitations inherent in traditional DApp architectures and DeFi-focused development libraries. Early projects like Dark Forest had no choice but to rely on existing DeFi-oriented frameworks and libraries, which became default choices despite being ill-suited for complex game logic.

Early patterns in creating fully on-chain games can be summarized in four aspects:

-

Multiple contracts accessing shared state: Multiple smart contracts might modify the same data or state, risking inconsistencies or conflicts. Sometimes the Diamond Pattern is used to mitigate this (a method addressing multiple inheritance issues in Solidity);

-

Writing multiple data structures: Each entity (e.g., soldiers, planets in-game) has its own distinct data structure and type;

-

Writing Getter functions: These return batches of elements from data structures, used to fetch initial states or data from chain. For example, a getPlanets() function returns a list of all planets;

-

Events: Each data structure includes events—specific features in smart contracts allowing apps to sync or update state when new blocks are added. For instance, creating a new planet triggers an event; apps listen for it and refresh displayed planet lists accordingly.

Building fully on-chain games this way is extremely painful. While ongoing optimization can reduce friction, it remains far removed from using a true general-purpose engine.

The Creator of Worlds—MUD Engine

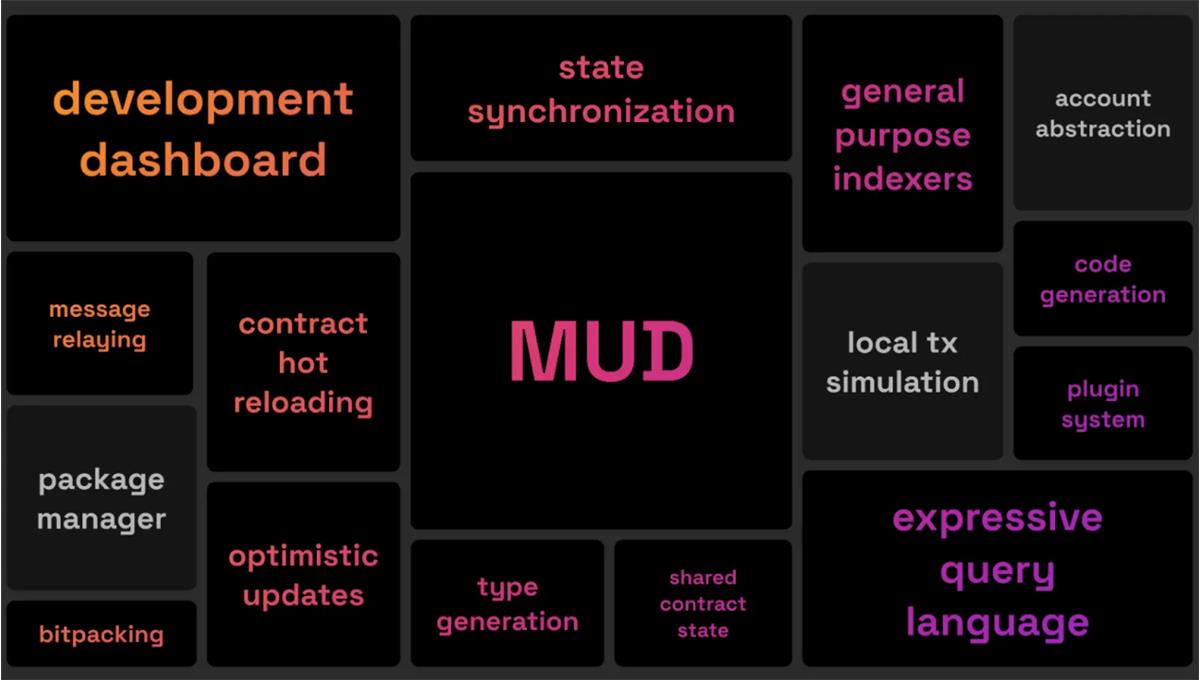

The MUD engine emerged from developers’ reflections on past and current problems. MUD is a framework for building complex applications on Ethereum. It provides conventions for organizing data and logic, abstracts low-level complexities, and lets developers focus on functionality. It standardizes how on-chain data is stored. With this standardized data model, MUD supplies all networking code needed to synchronize contract and client states.

The latest version of MUD currently includes five components:

-

Store: An on-chain database;

-

World: An entry-point framework offering standardized access control, upgrades, and modularity;

-

Tools: Ultra-fast development tools based on Foundry;

-

Client-side data storage: Magically mirrors on-chain state;

-

MODE: A Postgres database queryable via SQL.

EVM Compatibility and High Flexibility

MUD’s versatility extends beyond Ethereum mainnet. As long as the language is supported, MUD operates seamlessly on any EVM-compatible chain—including Polygon, Arbitrum, Optimism, and Gnosis Chain.

Moreover, although MUD is the preferred framework in the Autonomous Worlds and on-chain gaming communities, its use cases go far beyond. Crucially, MUD grants high flexibility, imposing no restrictions on specific data models. In short, anything implementable via Solidity mappings and arrays can be easily achieved in MUD. Regarding data availability, whether deployed on mainnet or Rollups, MUD applications match the accessibility of traditional Ethereum dApps like ENS and Uniswap.

Core Concepts

As a highly integrated suite of libraries and tools designed for complex on-chain applications, MUD revolves around three core ideas:

-

All on-chain state is stored in MUD’s Store database: Store is an embedded EVM database similar to SQLite, featuring tables, columns, and rows. Using Store enables more structured data management without relying on Solidity compiler storage mechanisms. It supports runtime table creation and allows hook registration to automatically generate indexed views, offering greater flexibility;

-

Logic is stateless and partitioned across contracts via custom permissions: The “World” acts as a central gateway coordinating different smart contracts’ access to “Store.” When a “World” is deployed, it creates a corresponding “Store.” Each table in “Store” is registered under a specific namespace. Functionalities (like transfer logic between addresses) added to the “World” are also registered under namespaces and referred to as “systems.” These “systems” are essentially smart contracts—but unlike traditional ones, they’re stateless and do not hold data directly. Instead, they read from and write to the “World Store.” Thanks to this design, “systems” can be reused across different “Worlds” as long as they’re deployed on the same chain;

-

No indexer or subgraph required—frontends stay synchronized automatically: When using Store (and by extension, World), on-chain data undergoes automatic introspection (self-inspection), with all changes broadcast via standard events. Through the “MODE” node, on-chain state is converted in real time into an SQL database, staying up-to-date with millisecond latency. Additionally, MUD offers query tools like MUD QDSL and GraphQL, simplifying frontend synchronization. For React developers, MUD provides specialized hooks enabling automatic binding and updating of component states.

Breaking the Chains

Using the three core principles above, let’s revisit earlier challenges and see how MUD breaks the shackles of complex application development.

-

Multiple contracts accessing shared state: MUD uses the “World” and “Store” structure to centrally manage on-chain state. All smart contracts (“systems” in MUD terminology) access and modify “Store” data exclusively through “World,” ensuring all state changes pass through a single entry point, minimizing inconsistency or conflict risks. With namespaces and paths, MUD enables fine-grained data access control. Different “systems” receive varying permissions, ensuring only authorized ones can alter specific data or states;

-

Data Structures: Unlike traditional Solidity storage, MUD’s “Store” introduces SQLite-like tables, columns, and rows, enabling more structured data handling. Each entity (e.g., soldiers, planets) gets its own table, with multiple columns storing various attributes;

-

Getters Functions: Thanks to MUD’s structured data storage, retrieving data becomes simpler and more intuitive. Developers can use SQL-like queries instead of writing dedicated getter functions. For example, fetching all planets requires querying the planet table directly—no need for a getPlanets() function;

-

Events: MUD features automatic introspection—any data change is instantly recognized and triggers appropriate events. Applications can listen to these events for state syncing or updates, eliminating the need to manually define events for every data structure.

The above explains basic MUD building blocks and partial usage of components. MUD can further support much more complex scenarios and applications.

Running the World: World Engine

Running fully on-chain games has always been a major challenge for Ethereum. With the rapid development of Rollups and the upcoming Cancun upgrade promising significantly lower costs and faster speeds, fully on-chain games are poised for takeoff. However, current mainstream Rollups are primarily designed for transactions, not tailored for on-chain games.

Argus’s flagship product, World Engine, is a sharded Rollup architecture purpose-built for fully on-chain games. As there is no public test yet, our analysis draws from project blogs and presentations.

What Kind of Rollup Do Fully On-Chain Games Need?

-

High throughput and TPS: Faster transaction processing, lower latency, better scalability;

-

Enhanced read/write capabilities: Most Layer 2 solutions optimize for heavy writes, but games require frequent reads (e.g., player positions), making read performance equally critical;

-

Horizontally scalable chains: Horizontal scalability means increasing system capacity by adding more nodes and resources, adapting to growing demand. This avoids the Noisy Neighbor problem (where one app’s activity negatively impacts others, causing resource contention and performance degradation);

-

Flexibility and customization: Customizable state machines designed specifically for games, including game loops and self-execution features;

-

Tick rate: Ticks are atomic units of game time. To achieve ultra-low latency, games need higher tick rates—or more blocks per second—to minimize delays.

Sharded Architecture

To achieve these goals, the team looked back to the late 1990s and early 2000s when online games like MMOs were emerging. Early online games, constrained by limited server and network technologies, needed ways to support massive player interactions. “Sharding” emerged as one solution—distributing players across different servers or “shards,” each independently hosting a subset of players, maps, and data.

For example, Ultima Online, an early MMORPG, implemented sharding. Different shards represented separate virtual worlds, each accommodating a fixed number of players. Benefits included:

-

Scalability: Distributing players across shards made it easier to scale and accommodate more users;

-

Reduced load: Sharding decreased player count and data volume per server, reducing server load and improving performance;

-

Avoid congestion: Sharding reduced overcrowding in specific areas, delivering smoother gameplay;

-

Geographic optimization: Assigning players to nearby shards reduces network latency and improves responsiveness.

How does this concept translate into World Engine? Unlike many prior sharded sequencers, “World Engine” is designed for specific needs, optimizing for throughput and runtime efficiency. To ensure high “tick rate” (update frequency per second) and fast block times, it defaults to synchronous operation. Its goal is rapid transaction processing to maintain seamless gameplay or system performance. It adopts partial ordering rather than requiring total transaction ordering—meaning not every transaction must occur after all others. This reduces sequencing overhead, better meeting demands for high throughput and quick block intervals.

Two key components exist: EVM Base Shard (an EVM chain) and Game Shard. The EVM shard is a pure EVM chain. The real secret weapon is the Game Shard—a mini-blockchain engineered as a high-performance game server. World Engine features a bring-your-own-implementation interface, allowing customization of this shard. Once built, the shard integrates into the base layer. By implementing a standard interface—similar to Cosmos’s IBC protocol—we can effectively establish a comparable specification, plugging our own shard into the World Engine stack.

Cardinal is the first implementation of a Game Shard on World Engine. It uses the Entity-Component-System (ECS) game architecture—a data-oriented design enabling parallelized game logic and increased computational throughput. It supports configurable “tick rates” up to 20 ticks per second—equivalent to 20 blocks per second on-chain. Additionally, it is self-indexing, eliminating the need for external indexers.

Furthermore, shards can be geographically positioned to reduce latency. For example, if a game’s sequencer is located in the U.S., Asian players face ~300ms delay before their transactions reach it—a significant issue in gaming. Attempting to play an FPS game with 200ms latency feels like playing slide-by-slide.

Conclusion: Reflections on Fully On-Chain Games

Fully on-chain games have long been a niche topic in Asia’s crypto circles. However, with Starknet launching its game engine Dojo and OP Stack demonstrating concept-validation tick chains, discussions around fully on-chain games are heating up. This article focuses on the ecosystem stemming from Dark Forest—currently the strongest and most vibrant on-chain gaming ecosystem.

Through historical and technical exploration, we see that Rollups and DApps still possess tremendous headroom. From a broader perspective, as infrastructure improves, not only games but also diverse complex ideas will be constructed via MUD and integrated on advanced Rollup architectures. A new paradigm for blockchains may very well begin with fully on-chain games.

There is much more to explore regarding fully on-chain games—such as the Loot-derived on-chain game ecosystem accelerating Starknet’s growth, state synchronization mechanisms, and the application of ECS architecture.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News