The Revelation of Fully On-Chain Games: A Pixel-Level Deconstruction of the Industry Chain

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Revelation of Fully On-Chain Games: A Pixel-Level Deconstruction of the Industry Chain

Comparison of Web2 and Web3 Game Value Chains in the Full-Chain Gaming Ecosystem

Author: @Minta, Analyst at PSE Trading

TL;DR

-

Fundamental concepts and significance of fully on-chain games

-

Value chain breakdown – Web2 game value chain vs. Web3 game value chain

-

Infrastructure layer – Game blockchains, game engines, communication architecture, rendering layers, etc.

-

Middleware – SDK integration, service integration, communication protocols, monitoring tools, etc.

-

Distributors – Analysis of different distribution strategies and case studies

01 Overview

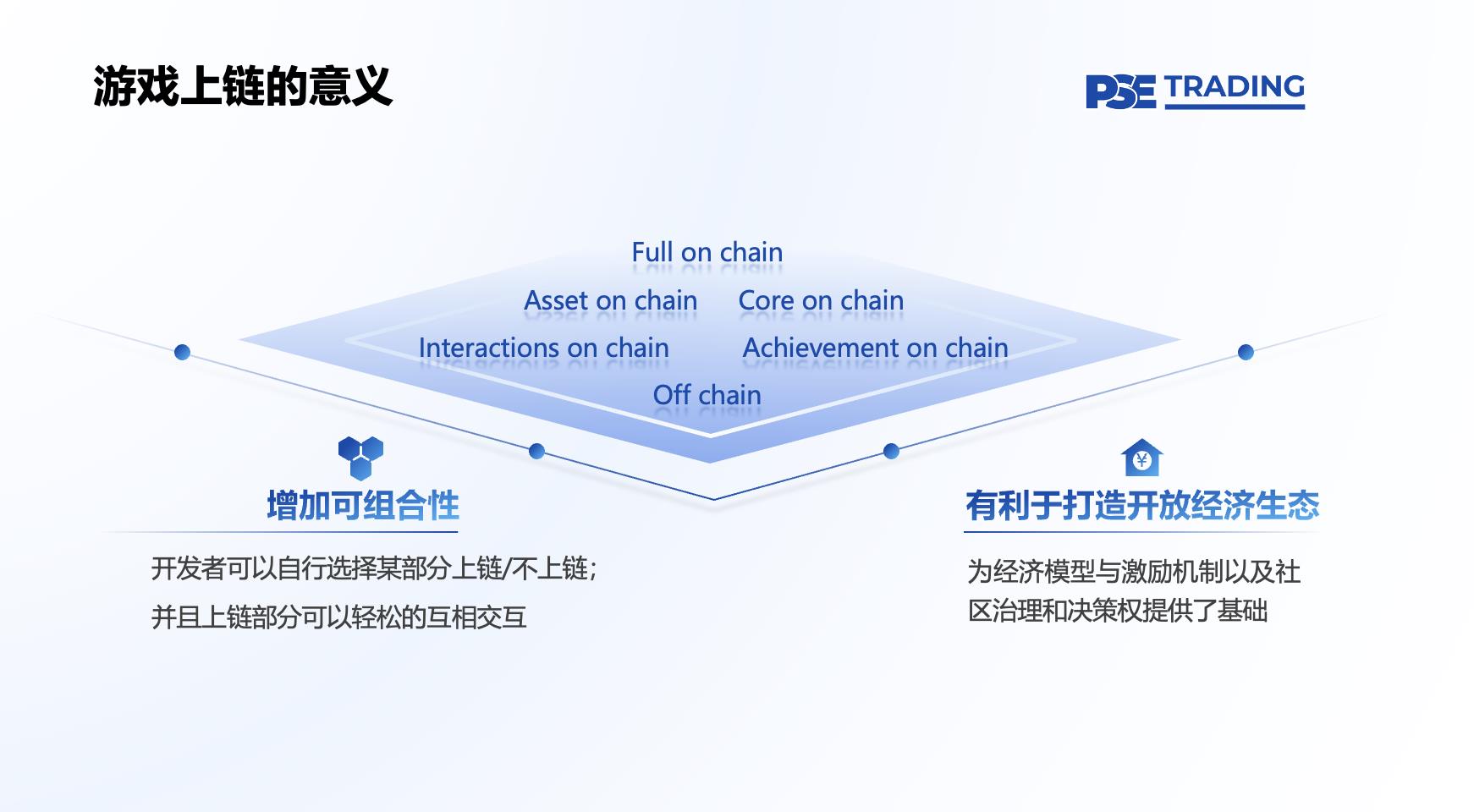

A fully on-chain game refers to a game whose logic and data are entirely stored on the blockchain, relying on smart contracts for operation and interaction. In contrast, partially on-chain games store only certain game elements on the blockchain. Depending on what is stored on-chain, these can be further categorized into core logic on-chain, assets on-chain, achievements on-chain, and interactions on-chain.

Core logic on-chain typically involves storing game algorithms and key data on the blockchain. For example, in a chess game, the rules of chess, board state, and all gameplay-related data are recorded on-chain. Each move and win/loss determination is executed via smart contracts on the blockchain. Asset on-chain means that in-game virtual items, characters, or other resources are placed on the blockchain, allowing players full ownership, trading rights, and management over these assets—providing economic incentives, encouraging player participation in ecosystem development, and enabling open economies.

Achievement on-chain is another interesting concept. Players’ accomplishments within the game are recorded on the blockchain as permanent records of their gaming journey, giving recognition beyond the confines of any single game environment.

Expanding further, we get interaction on-chain. This includes not just achievements but also players’ social interactions within gaming communities—such as chats with others or participation in community events—all logged on-chain like an interactive gaming resume, making every engagement meaningful.

Of course, fully on-chain games remain an emerging concept still in early development. What’s clear is that abstracting various modules of games and placing them on the blockchain opens up new possibilities for innovation. However, the specific impacts of fully migrating games onto the blockchain are still being explored across the industry through trial and error. From a qualitative standpoint, two primary motivations stand out as the strongest rationale for moving entire games onto the blockchain:

Enhanced Composability:

By using smart contracts to build modular game components—including security audits, access control, and resource metering—developers enable greater flexibility. Traditional games struggle to adapt to this model, let alone recombine composable modules. Additionally, smart contracts facilitate more UGC (user-generated content) modules, lowering barriers to content creation, promoting UGC development, enhancing playability, and increasing content composability.

Open Economy:

With the growing number of Web3 players and improved interoperability between ecosystems, game economies become more open, enabling players to participate in in-game economic activities in increasingly flexible ways.

PSE Trading’s follow-up articles in this series will delve deeper into the rationale behind onboarding games to the blockchain. This article focuses on clarifying the concept of fully on-chain games and presenting a comprehensive view of the value chain, aiming to give readers a clearer understanding of each segment within the fully on-chain game industry.

02 Value Chain

2.1 Web2 Game Value Chain

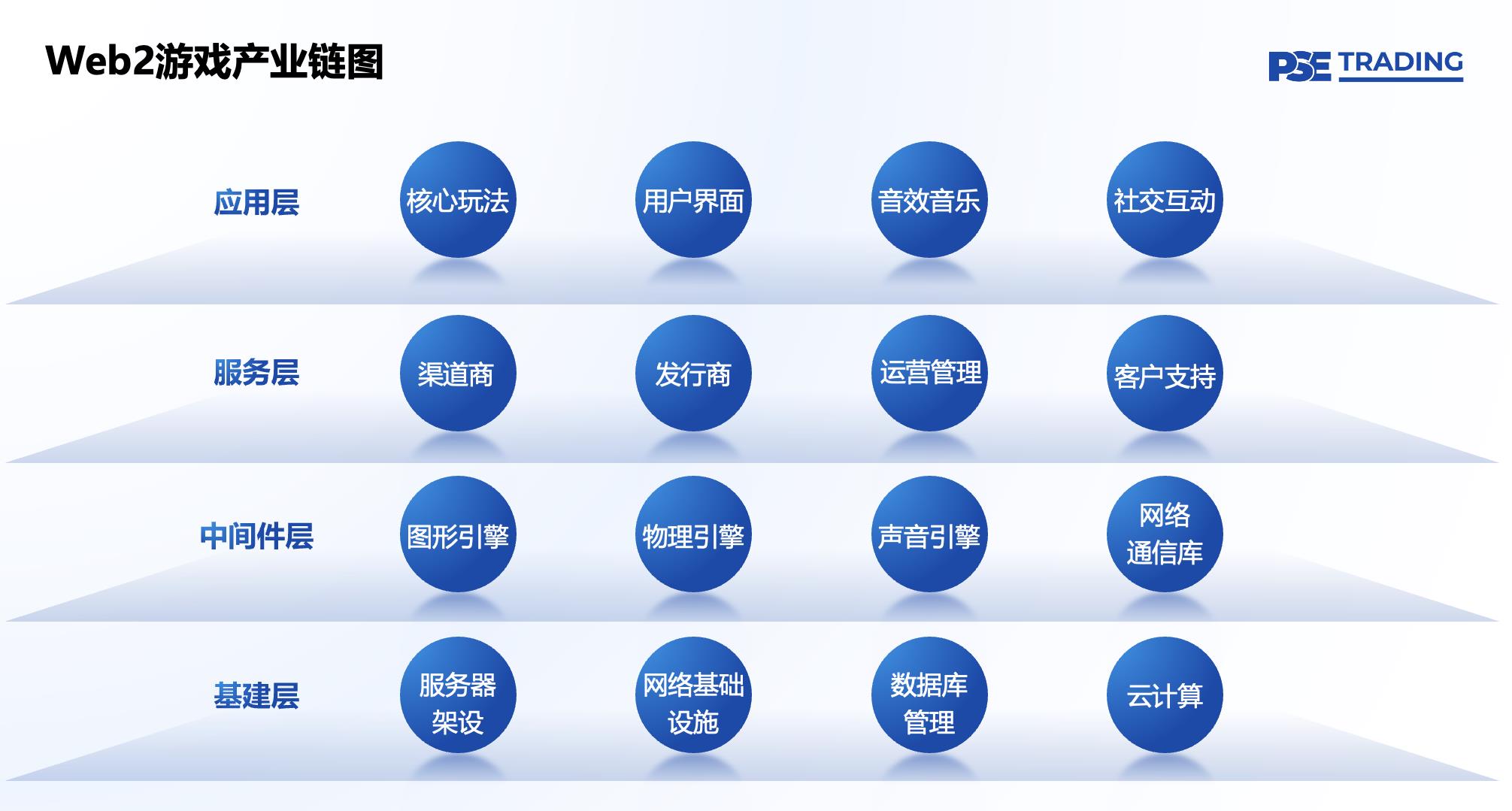

When examining the value chain of the Web3 gaming industry, we can draw insights from the mature Web2 gaming sector. The Web2 gaming industry can broadly be divided into four key layers: infrastructure layer, middleware layer, service layer, and application layer.

The infrastructure layer forms the foundation of the entire gaming ecosystem, encompassing essential technologies and infrastructures required to run games. For instance, games need servers—services like Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Microsoft Azure provide foundational server hosting. Network infrastructure supports online functionality, including network hosting services.

The middleware layer primarily addresses technical complexities in game development and operations. Graphics engines handle rendering to deliver visually rich experiences. Physics engines simulate object behaviors for realistic interactions—Havok and PhysX are well-known examples that bring dynamic physical effects to life.

The service layer manages critical processes between the game and end users, including distribution, operations, customer support, and end-user services. Distributors (or channels) play a vital role by bringing games to market and ensuring wide reach. Operationally, marketing strategies and promotional campaigns are implemented here to boost visibility and appeal.

The application layer is where the core gameplay experience is delivered to players—the interface, mechanics, audiovisual design, and social features come together here.

In summary, the traditional Web2 game value chain interconnects infrastructure, technical middleware, and application design. Yet, as a highly industrialized field, its value chain is also finely segmented, with specialized tools or teams handling each scenario or requirement. Drawing from the Web2 game value chain helps us better understand the structure of the Web3 gaming ecosystem.

2.2 Web3 Game Value Chain

Compared to the maturity of the Web2 gaming space, the fully on-chain gaming domain remains in its infancy. As such, the granularity of the full-chain game industry chain isn’t yet as refined as in Web2. Nevertheless, the upstream-downstream relationships in the fully on-chain game industry mirror those in the Web2 value chain.

The fully on-chain game industry can still be segmented into four key layers corresponding to those in Web2: infrastructure layer, middleware layer, service/tool layer, and application/game layer.

03 Infrastructure Layer

Within the gaming industry landscape, the infrastructure layer acts as a solid pillar. From server operations and network connectivity to player data management, every component contributes to building the virtual world of games.

As previously mentioned, the main difference between Web3 and Web2 games lies in the fact that Web3 fully on-chain games involve on-chain deployment. Moreover, in the on-chain gaming ecosystem, the greatest network effect comes from game composability, scalability, and the integration of game assets with other games built on the same ecosystem and engine. Therefore, two crucial parts of Web3 full-chain game infrastructure are blockchains specifically designed for games and scalable on-chain game engines.

3.1 Game Blockchains

Currently, there are mainly two types of game-related blockchains: Layer 2 chains dedicated to gaming and Layer 1 chains that encourage game ecosystems. Examples are listed below:

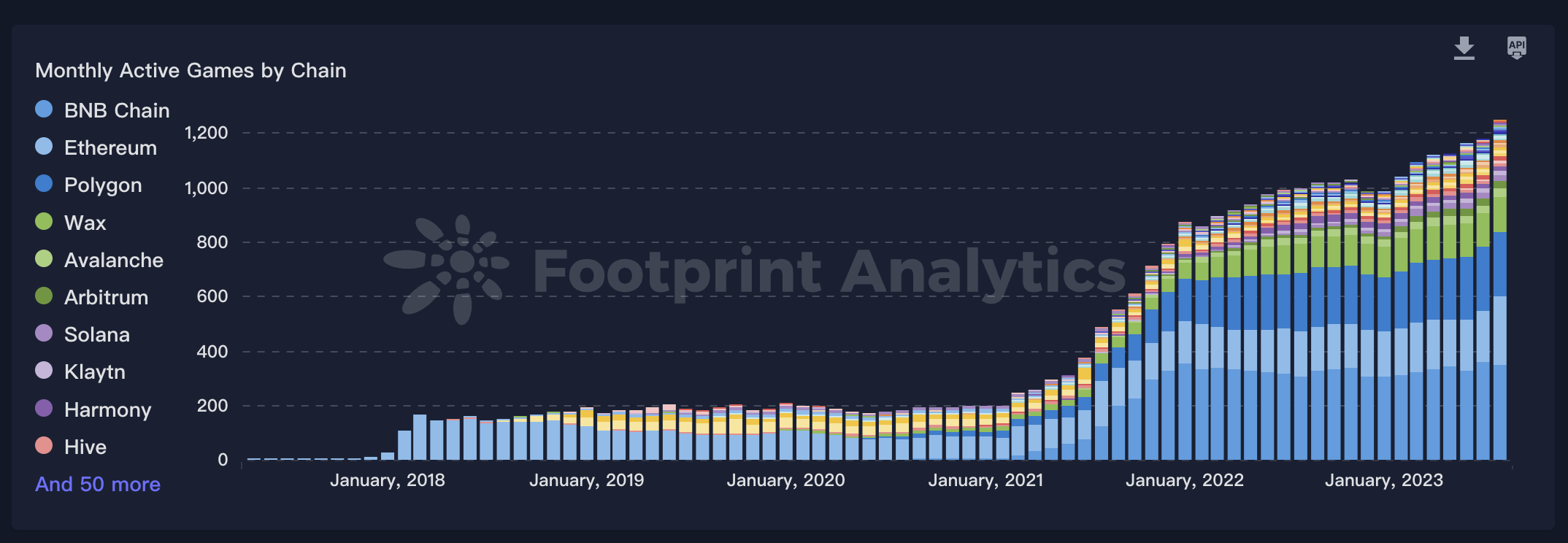

From a data perspective, according to Footprint, BNB Chain, Ethereum, Polygon, and Wax continue to lead the GameFi space, hosting over 80% of on-chain games.

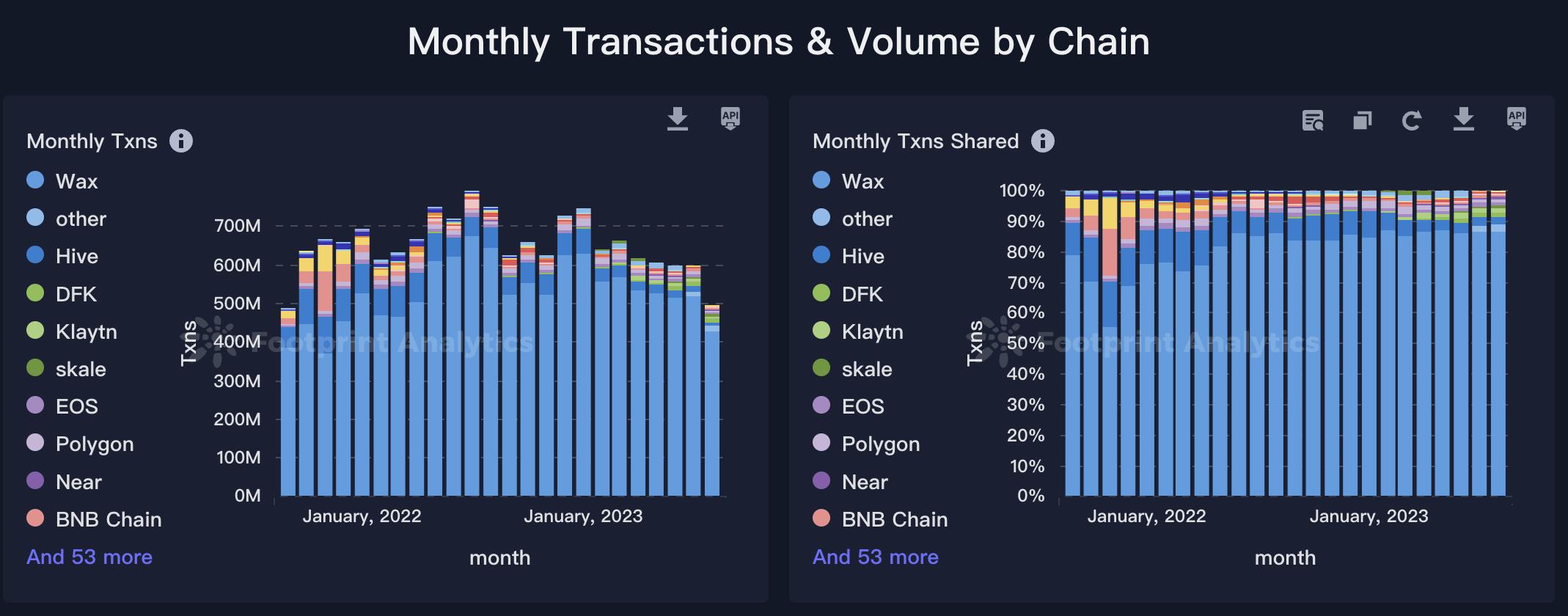

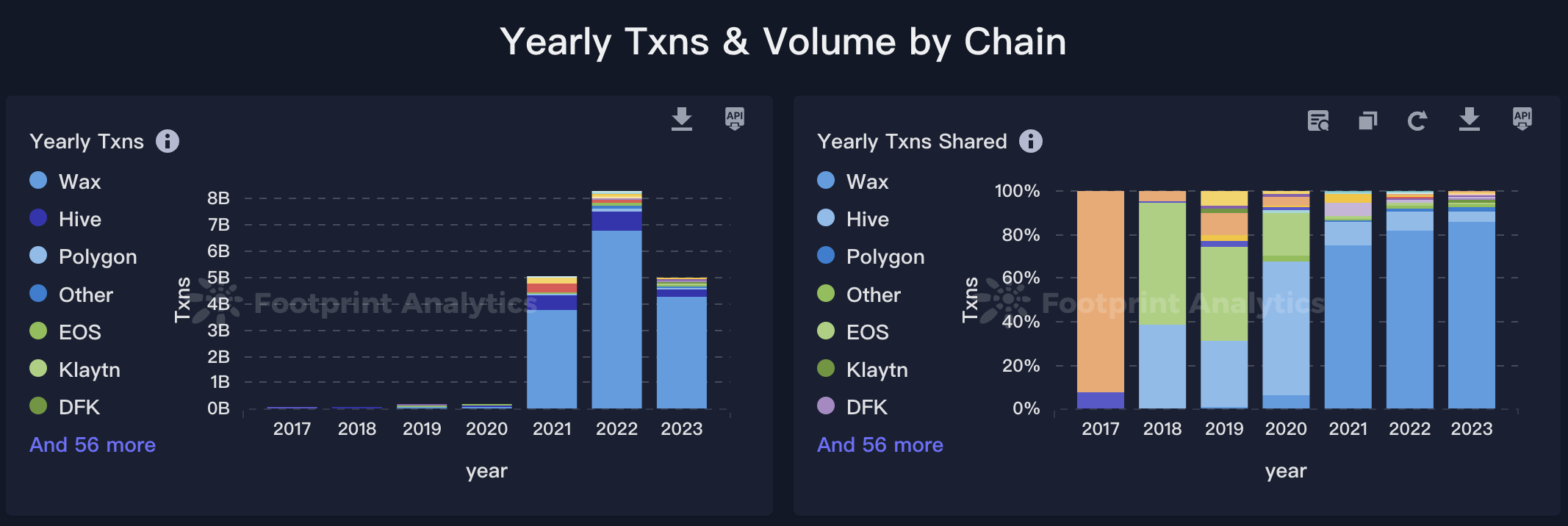

Based on Footprint's monthly transaction data for on-chain games (data截至 August 2023), the Wax ecosystem has maintained absolute dominance in transaction volume. As of writing, Wax recorded 429.24 million transactions in August 2023, accounting for 86.56% of all game transactions across chains.

According to Footprint's annual transaction data (data截至 2023), Wax has held a dominant position in transaction volume since 2020, with little change in the ranking of major blockchain game transaction volumes during this period.

3.2 Game Engines

Much of the code and graphical assets in game development are reusable. Thus, developers consolidate commonly needed code and assets into a software development kit (SDK), known as a game engine, to improve efficiency and streamline the development process.

For example, Unity provides developers with rich tools and resources for creating both 2D and 3D games. Unreal Engine excels in graphics rendering and visual effects and is widely used in high-quality AAA game development.

Some Web3 game studios, such as Planetarium Labs and Lattice, are developing their own Web3 game engines to allow developers to write complex game logic and interactive content.

Referencing IOSG Ventures - Ishanee's summary of Web3 game engines, Mud and Dojo are public goods, while Argus and Curio were developed by commercial teams through fundraising:

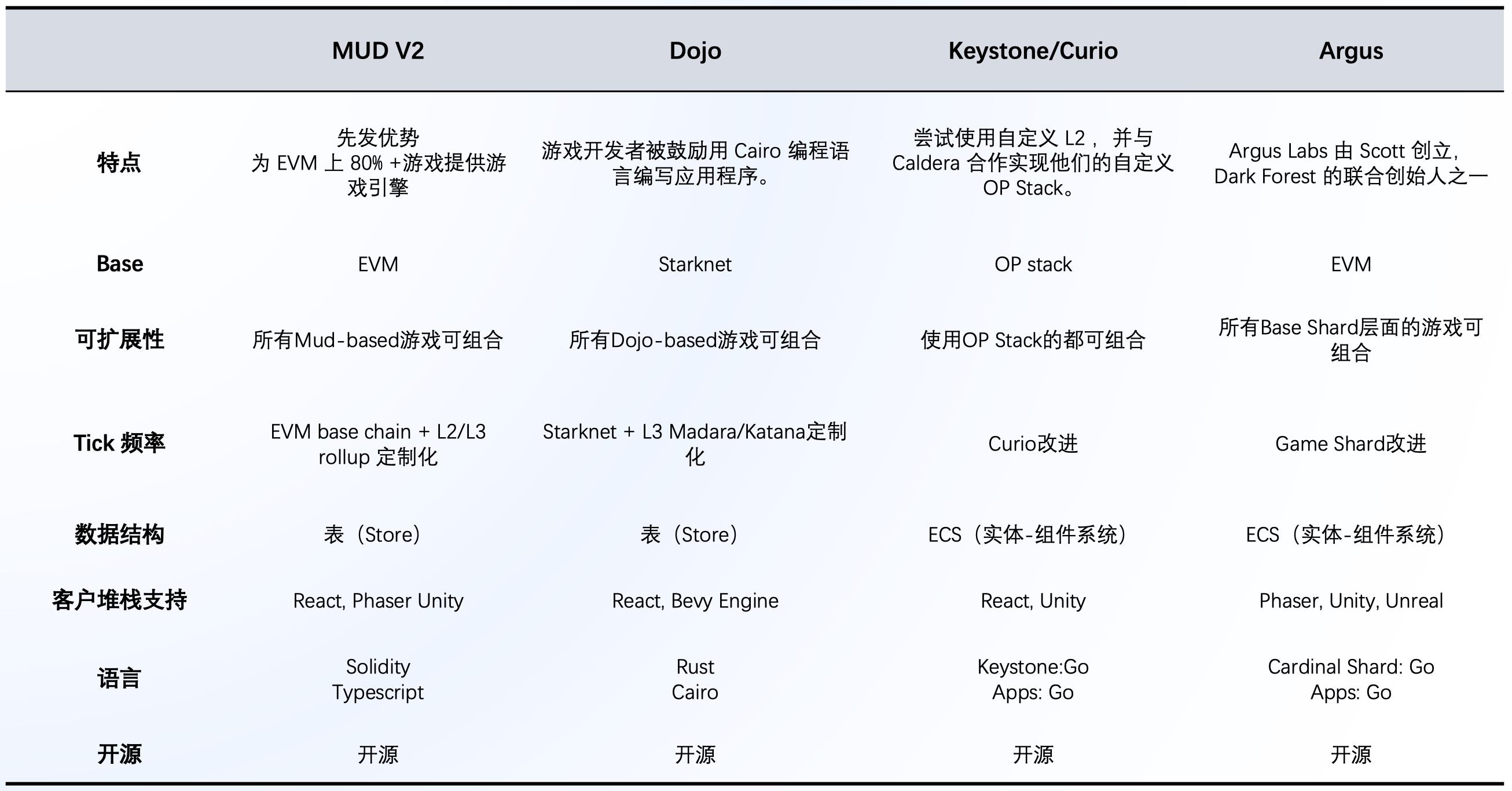

Summarizing IOSG Ventures - Ishanee's summary, the functional comparison of the four game engines is shown below:

Among them, MUD pioneered Web3 game engines with first-mover advantage and a large player community. Curio's Keystone is building a game design engine focused on increasing blockchain ticks. Argus specializes in various scaling solutions and frameworks for game design. Dojo emphasizes building games where all logic can be proven to have been executed off-chain.

Beyond full engines, some tools focus on specific modules, such as:

- Endless Quest: Generates consistent narratives in AW, including metadata and art

- MUDVRF: A MUD module for generating on-chain random numbers in games

- DeFi Wonderland: Account management module using burner clients for wallet usage

- MUD Scan: Leaderboard for MUD games

- Argus: Plans to launch an EVM Layer 2 with plug-in data availability layer, emphasizing customizability.

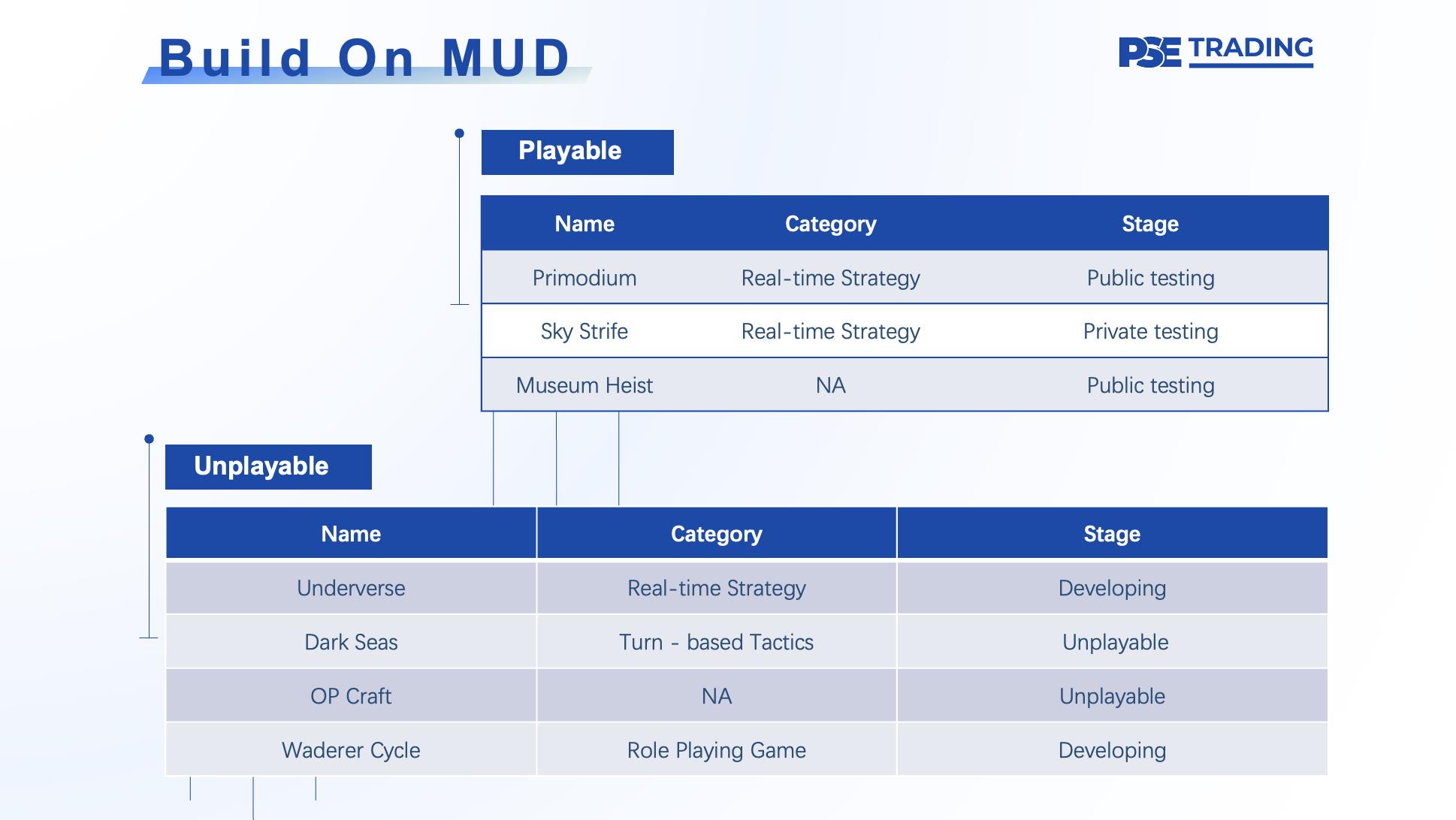

Currently, MUD v2 and Dojo are leading in development progress, with several fully on-chain games already launched using these engines. Below is a summary of these titles:

Overall, current game engines are actively working to increase tick rates and scale networks to support more complex in-game interactions on blockchain.

However, the biggest issue facing fully on-chain game engines today is the lack of unified standards. Drawing from Web2 game evolution, game engines exhibit strong Matthew effects—eventually, only 1–2 leaders will dominate and set industry standards.

Following general industry trends, the engine that first achieves product-market fit (PMF) with a breakout full-chain game will gain significant competitive advantage.

3.3 Communication Architecture

A classic challenge in traditional game development is managing module communication structures—specifically, the relationships and hierarchies among different in-game characters or objects.

Take “aquatic creatures,” “terrestrial creatures,” and “amphibians” as an example. Aquatic creatures naturally exist in water, so their associated traits and behaviors are relatively straightforward to implement. Similarly, terrestrial creatures reside on land, and their environmental interactions are easier to manage. Amphibians, however, present a special case—they must survive and act in both environments, posing a design challenge. Whether to place amphibians in water or on land, or how to switch between environments, involves complex logic and interaction. Traditional communication architectures may struggle here due to the need for seamless transitions and adaptive behavior across environments.

To address this, Web2 game development introduced the ECS framework—Entity-Component-System. ECS is a more flexible communication architecture that separates data (components) from behavior (systems), enabling more efficient and adaptable data handling. Using ECS, amphibians can seamlessly transition between water and land, dynamically adjusting their attributes and actions based on the current environment. This involves techniques like state management, environment detection, and dynamic property changes.

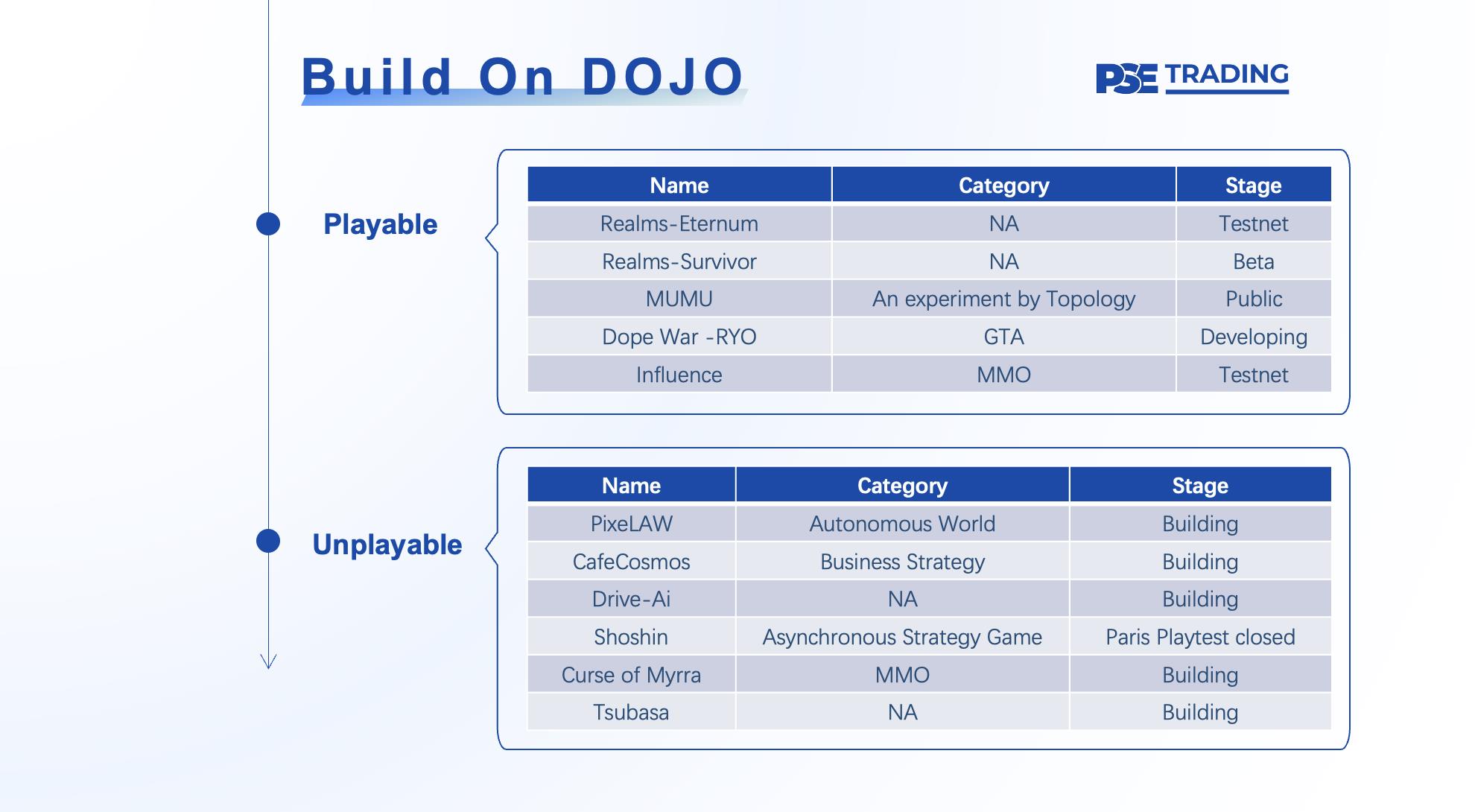

Web3 games adopt the ECS philosophy to develop Web3 Communication Infrastructure—ARC (Action Registry Core). Its technical core consists of three parts:

- The unit is Action; in ARC, the core element of the game is treated as an action. Characters, events, decisions—all are abstracted into actions, making game interactions and logic more flexible and scalable.

- Only final game results are stored on-chain;

- All other data is stored off-chain and accessed via indexers and relay infrastructure.

In summary, ARC serves as the communication backbone for Web3 games, drawing inspiration from ECS by treating actions as objects, storing only game outcomes on-chain, and integrating off-chain data with supporting infrastructure—offering greater flexibility, scalability, and efficiency for Web3 games.

Currently, no standalone project solely develops the ARC communication architecture, but major game engines and independent Web3 game studios are actively contributing to it.

3.4 Rendering Layer

The most famous rendering infrastructure in Web2 is Unreal Engine. Web3, leveraging decentralization, has created a distributed rendering protocol—RNDR.

RNDR is powered by Render Network, a protocol utilizing decentralized networks for distributed rendering. Render Network’s parent company, OTOY.Inc, was founded in 2009, with its GPU-optimized rendering software OctaneRender. For creators, local rendering demands high computational power, creating demand for cloud rendering. But renting servers from AWS or Azure can be costly—this gap led to Render Network, which connects creators with ordinary users who have idle GPUs. Creators get affordable, fast, and efficient rendering, while node operators earn extra income using spare GPU capacity.

Participants in Render Network fall into two roles:

• Creators: Initiate rendering tasks and pay using fiat (via Credit) or RNDR tokens. (Octane X is the tool used to post tasks, compatible with Mac and iPad. 0.5–5% fees cover network costs).

• Node Providers (idle GPU owners): Idle GPU owners can apply to become node providers. Task matching priority depends on reputation from past completed jobs. After task completion, creators review and download rendered files. Once confirmed, fees locked in smart contracts are released to the node provider’s wallet. This setup allows providers to monetize idle GPUs while boosting overall network efficiency.

In short, Render Network’s unique architecture solves performance issues in rendering while creating win-win opportunities for creators and idle GPU owners.

04 Middleware Layer

4.1 SDK Integration

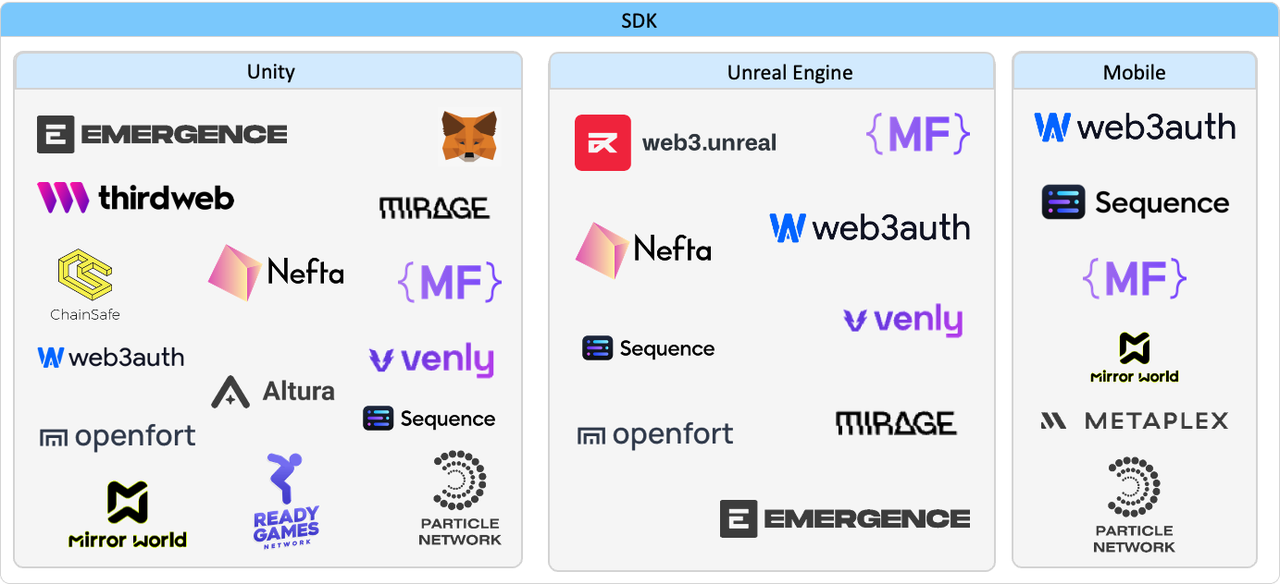

Similar to game engines, SDK integration platforms offer one-click deployment tools—but these SDKs target more specialized functions.

Projects enter the SDK integration space from various angles. Below are three common GTM strategies currently observed:

Case 01 - SDK Store

The first type is an SDK store—a marketplace where projects aggregate available SDKs, allowing developers to search and select SDKs based on needs.

For example, the Unity Asset Store offers verified SDKs from MetaMask, Magicblock (Solana), Tezos, Nefta, Immutable, and others. Web3.Unity by Chainsafe Gaming is another popular open-source option outside the Asset Store. Unreal Engine developers may consider Web3.Unreal by Game7, Emergence, or Mirage.

Case 02 - Specialized Functionality

SDKs targeting specific functions include:

NFT Marketplaces:

- No-code solutions: Altura or Recur allow developers to create web-based external NFT marketplaces without coding.

- In-game markets: These require higher customization. Existing solutions often provide APIs or Unity/Unreal SDKs to simplify common marketplace functions on blockchain—like listing NFTs, viewing inventory, or completing purchases.

Eg: Nefta, Particle Network, Venly, Sequence, Mirror World, Fungies, and Chainsafe Gaming.

In-game Services:

Some companies, like Aqua, offer no-code/low-code in-game marketplace-as-a-service. By embedding systems directly into Unity game clients, players can access virtual markets inside the game to buy cosmetics, character skins, etc., without leaving gameplay. Through Unity integration, Aqua simplifies the process for developers to deliver rich in-game transaction experiences.

In-game Store System SDKs:

Though not strictly within the gaming niche, providers like Ready Games and MetaFab offer customized in-game store system SDKs/solutions.

4.2 One-Stop Service Providers

One-stop service providers typically offer the most comprehensive blockchain integration tech stacks, delivering end-to-end services for developers and publishers.

Case 01 - Forte

Forte is a blockchain gaming platform offering a suite of services designed to create frictionless blockchain gaming ecosystems for developers, communities, and players. These services span the entire game lifecycle, including market-making, compliance, tool development, player services, game creation, and economic modeling. Forte also funds creator grants to encourage game development.

Additionally, Forte integrates DeFi and NFTs to unlock new revenue streams for creators. It provides marketplace and trading services, simplifies digital wallet experiences, and includes built-in compliance components such as anti-money laundering (AML) and KYC. With these features, Forte helps existing games build scalable token economies, enhancing sustainability and profitability.

Case 02 - One-Stop Consulting

Many game studios, such as Big Time’s Open Loot and Horizon’s (Skyweaver) Sequence, offer consulting/incubation services. Leveraging their extensive experience, they help Web2 developers transition into the market.

For example, Open Loot offers technical integration plus marketing support, payment processing, and comprehensive game analytics. Horizon’s Sequence assists Web2 games in transitioning to Web3 by tokenizing virtual items and enabling blockchain-based ownership transfers. These services expand market reach and empower developers to seize new business opportunities in the digital realm.

4.3 Communication Protocols

Case 01 - XMTP

XMTP is an early Web3 communication protocol project aiming to build a unified decentralized inbox system, providing communication infrastructure for all dApps. Think of it as a decentralized version of XMPP (Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol) for blockchain. With a built-in XMTP client, users can send and receive encrypted XMTP messages within apps, authenticated via wallet signatures. This ensures message encryption and resistance against spam. Currently, the protocol only supports peer-to-peer messaging (one-on-one). Despite limitations, XMTP lays foundational groundwork, making decentralized communication more practical and feasible.

Case 02 - Web3MQ

Web3MQ is an open-source, decentralized, secure communication protocol striving to become native crypto communication infrastructure. Building upon XMTP, it offers a multi-functional solution integrating push notifications, chat, and community features.

Moreover, Web3MQ is compatible with a wide range of social identity and social graph protocols, using communication as a bridge to unlock the potential of social connections. It integrates existing Web3 ecosystems—like Web3 storage (e.g., IPFS) and computing (e.g., Internet Computer)—to enrich the messaging ecosystem. Users can customize configurations for advanced privacy protection and personalized features. Compared to current Web3 communication protocols, Web3MQ stands out as a more mature and comprehensive solution.

4.4 Economic System Monitoring Tools

Most Web3 games feature built-in economic systems, making economic health critical. Hence, tools emerged to simulate, test, and monitor whether GameFi systems are functioning sustainably.

Machinations provides game developers with a visual way to design and optimize in-game economic loops. To date, over 20 Web3 games have partnered with Machinations to enhance their economic designs.

For instance, imagine a Web3 strategy game where players gather resources, build cities, and recruit armies. Resources like wood, stone, and gold interact within the game, influencing player decisions. Using Machinations, developers can create diagrams that visually represent resource flows, production, consumption, and interdependencies. They can define generation rates, usage patterns, and costs—for example, setting wood and stone for city construction, gold for army recruitment, and assigning costs to actions like building structures, recruiting units, or trading.

With Machinations, developers can simulate how the in-game economy behaves, observing how resource dynamics affect the overall ecosystem. If certain resources become too scarce or abundant, developers can tweak parameters to balance the economy, making gameplay more engaging and sustainable.

4.5 Others

With the advancement of Web3 and blockchain technology, new protocols aim to extend small aspects of games or specific NFT functionalities, adding utility to in-game tokens.

For example, Furion enables fractionalization of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) into corresponding ERC20 tokens, which can be freely traded and circulated on the Furion platform, supporting financial operations like lending, borrowing, long/short leveraged positions.

To illustrate, suppose a digital artwork by an artist is minted as an NFT. Furion’s platform can split this NFT into divisible ERC20 tokens representing shares of the artwork. These tokens can be traded on Furion’s marketplace, allowing art enthusiasts to purchase partial ownership. Furthermore, Furion supports financial instruments—users can leverage their ERC20 holdings for investment and trading activities.

This opens new possibilities for GameFi token models—for example, instead of launching a token directly, a project could first issue NFTs with utility, then use those NFTs as underlying assets to issue tokens.

05 Channels / Distributors

In the gaming industry, channels and distributors play pivotal roles. Looking back at Web2.0-era game distribution, two primary models existed.

First, platform-based distributors like Steam, Epic, Nintendo—their key success factor (KSF) is platform traffic. These distributors rose to prominence after launching breakout games or acquiring iconic IPs. Successive hits helped them accumulate massive user bases, evolving from game publishers into distribution platforms. Over time, they expanded services, features, and social interactions, becoming comprehensive gaming platforms that strengthened user retention and brand moats.

Second, hardware and device manufacturers like Huawei and Apple—still driven by user traffic. They attract users by releasing high-quality devices and increasing device penetration. When users buy and use these devices, they also engage with the ecosystem and services offered, making them powerful game distribution channels.

Both platform-based distributors and hardware/device makers play crucial roles in the gaming industry. By accumulating user traffic, owning iconic IPs, and building comprehensive ecosystems, these distributors drive industry growth at multiple levels. Currently, Web3 lacks a mature distribution channel system. Below are several distribution strategies currently adopted in the Web3 gaming space.

5.1 Path One - Classic Web2 Approach

This path mirrors Web2-era models like Steam, Nintendo, or TapTap—aiming to become the Web3 equivalent of TapTap by attracting users with high-quality games and gradually evolving into a distribution platform.

The advantage is that this model has been validated in Web2. However, the downside is equally evident—it requires heavy investment and exceptional team capabilities. Moreover, it remains unclear who the first target audience (TA) for Web3 games is. The debate over whether to focus on native Web3 users or draw traffic from Web2 continues unresolved, making the platform’s target audience ambiguous and challenging GTM strategy and product planning.

Case 01 - XterioGames

XterioGames raised $15 million from Binance Labs in July 2023. Xterio is a Web3 gaming platform and publisher planning to release cross-platform games on PC and mobile. Its ecosystem will also distribute digital collectibles via Xterio’s web platform and marketplace.

For players, Xterio offers a game library, NFT marketplace, on-chain interface, decentralized identity system, wallet, and community apps. For developers, Xterio reduces the burden of blockchain programming, helps secure funding and promotion, and creates a seamless path from development to launch and ecosystem integration.

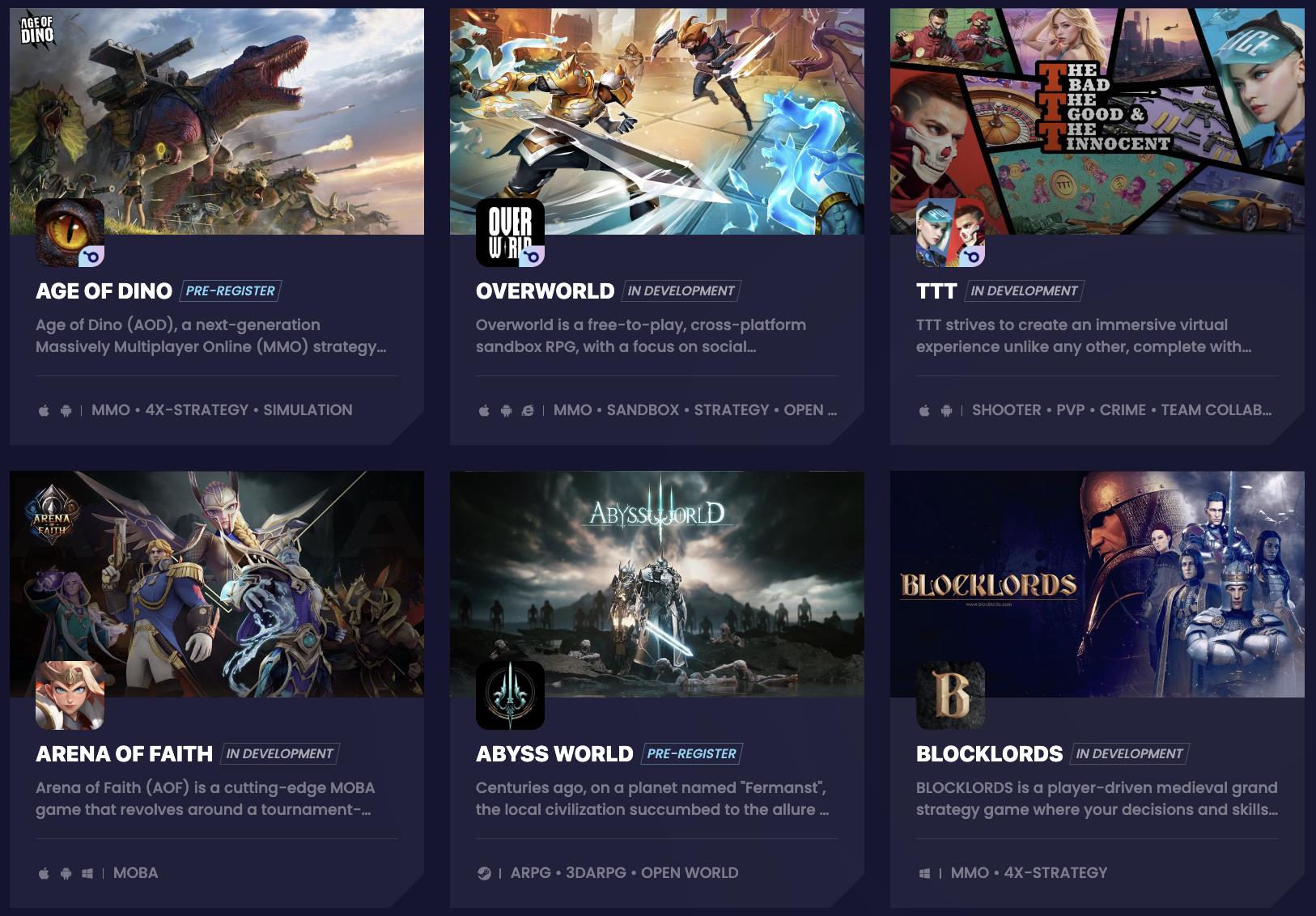

Overall, XterioGames is actively exploring Path One, developing several core games and publishing others through acquisitions and partnerships. The image below shows some of XterioGames’ released titles.

Case 02 - Cartridge

Cartridge is a Starknet-based Web3 game integration platform positioned as the "Web3 Steam."

For developers, Cartridge offers Cartridge Controller and Dojo Engine, streamlining development with a unified framework and lowering entry barriers. For players, it enables quick discovery and access to games. Several playable games are already available. The image below shows a few examples.

Case 03 - Createra

Createra, backed by a16z, is a user-generated content (UGC) metaverse engine enabling creators to build, distribute, and monetize MetaFi games. Createra offers users exclusive crypto-native autonomous worlds with features like cross-play and instant access. Everything built on land within the platform is tradable—models, games, APIs, etc. The project emphasizes integrating ERC-6551 with gaming, particularly in decentralized identity (DID).

Overall, Createra can be seen as a Web3 version of Minecraft. By partnering with popular IPs like BAYC, it encourages Web3 users to enter the game world, create personal virtual spaces, and interact across the ecosystem. The project continuously adds new features—mapping achievements to DIDs, embedding mini-games—evolving into a gamified, integrated distribution platform.

5.2 Path Two - Crypto-Native Exploration

Path Two explores more crypto-native approaches—using player interactions to attract users and concentrate traffic. Current experiments include achievement systems, aggregated airdrops, educational systems, and decentralized identity (DID) construction.

Compared to Path One, this approach is lighter, less capital-intensive, but demands stronger user operation skills. Teams must quickly identify trending Web3 user interactions and embed them into their platforms to effectively drive user acquisition.

However, Path Two remains largely unproven in the market. Which path will ultimately prevail is highly uncertain. Teams must maintain sharp market awareness, continuously adapt strategies, and closely track evolving user needs. Below are notable examples pursuing Path Two.

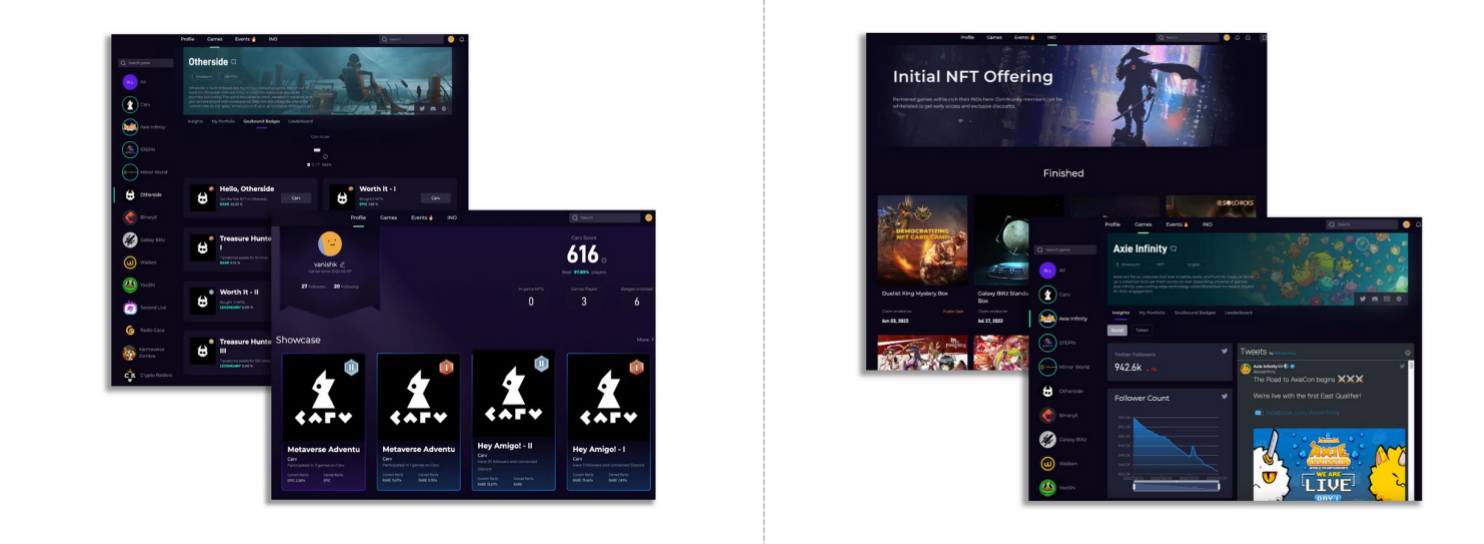

Case 01 - Carv

Carv is a GameID platform starting with an achievement system. Interestingly, it calculates a reputation score based on users’ historical on-chain data. Their GameID presentation combines this reputation score with earned Soulbound Tokens (SBTs). The platform verifies on-chain achievements and issues corresponding SBTs upon qualification.

For listed projects, the platform provides social data analytics, helping players quickly discover promising, high-engagement games and track latest social trends of followed games—very helpful for users. The platform also features an INO section for NFT launches, though this relies heavily on the team’s BD capability, with only 10 launches so far.

Case 02 - DeQuest

DeQuest is a GameID platform built around a quest system, featuring gamified design where users’ GameIDs appear as avatars (future-compatible with sandbox entry). Completing quests unlocks equipment and skills.

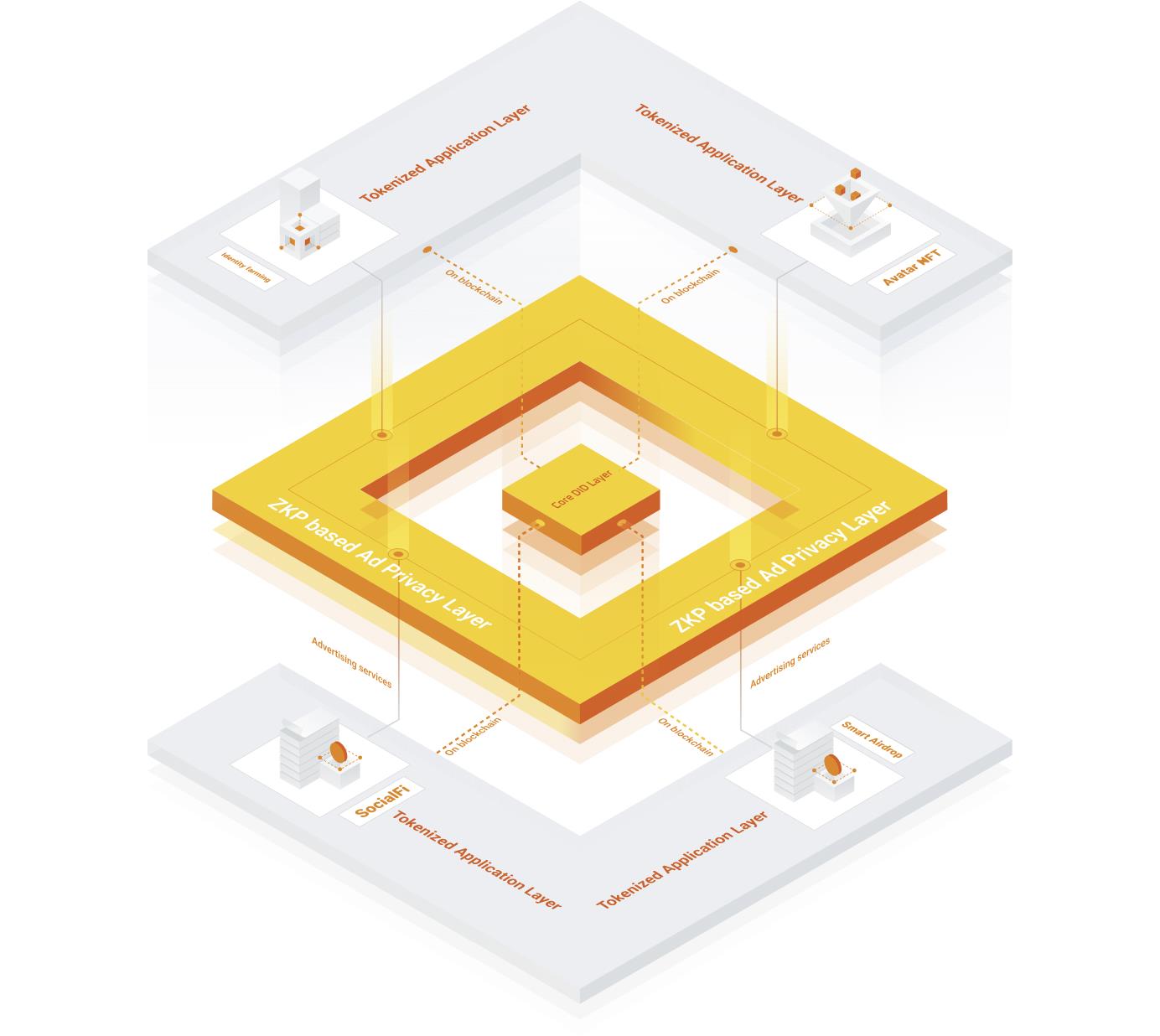

Case 03 - Parami

Parami Protocol is an ERC5489 protocol revolutionizing creator economies on the internet, turning NFTs into gateways for Web3 content discovery. For example, on a social media platform, users can upload posts, photos, and social data to the blockchain via Parami Protocol. Data is securely stored and encrypted, with users granting permissioned access to others or institutions.

Beyond data sharing and privacy, Parami actively collaborates with gaming projects, expanding possibilities. A game built on Parami could map player achievements and item ownership to NFTs, enabling richer asset value transfer and interaction across the Web3 ecosystem. This elevates player experience, bridging virtual and real worlds more tightly.

In sum, Parami Protocol pioneers new models for data governance and content discovery, while opening doors to becoming a traffic gateway in the gaming space.

5.3 Path Three - Chain & Exchange Incubation

In the Web2 ecosystem, content providers (CPs), such as game developers, typically pay distribution platforms for exposure and traffic. However, in today’s Web3 ecosystem, due to a shortage of high-quality content, platforms now pay top CPs instead. Specifically, many blockchains and exchanges host hackathons—an exemplary case. Outstanding creators are selected and supported with resources and training to foster quality content within their ecosystems, driving broader ecosystem growth.

For instance, Stepn, the 2021 GameFi leader, is a classic example. According to Stepn’s co-founder, winning the Solana hackathon was a pivotal moment—from zero to one—boosting team morale and securing initial resources.

Today, numerous blockchains and exchanges run hackathons—even collaborating jointly to incubate projects—creating excellent opportunities for industry advancement and breakthrough innovations.

Closing Thoughts

This article focuses on clarifying the concept of fully on-chain games and presenting a panoramic view of the value chain, aiming to give readers a clearer understanding of each segment in the fully on-chain gaming industry. PSE Trading’s follow-up articles in this series will explore fully on-chain games from various angles in greater depth.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News