Interview with Natural, Investment Lead at Mask Network: Why Are Full-Chain Games Rising, and What Is Their Appeal?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Interview with Natural, Investment Lead at Mask Network: Why Are Full-Chain Games Rising, and What Is Their Appeal?

The process from Cefi to Defi is the process from GameFi to fully on-chain games.

Chain Game Camp S1 hosted an intense internal discussion on blockchain gaming, featuring a conversation with Chen Yuetian from Firebird about the transition from 2.0 to 3.0 (Only 3% of 167 High-Quality Game Companies Have Transitioned to Web3 | In Conversation with Firebird’s Chen Yuetian). We also spoke with Tianran, Head of Ecosystem and Investments at Mask Network, a staunch believer in on-chain games—what new thoughts and actions has he taken?

Below is a transcript of part of the session held on August 1:

Wanwudao: How did fully on-chain games evolve, and what stage are they at now?

Today I’ll mainly share the development history of fully on-chain games, focusing on two major camps: Dark Forest and Loot. Anyone who's been in the space for a while has likely heard of at least one. When people first encounter them, they think it's impressive—but aren’t sure what to do with it. The evolution of these two leading projects in the on-chain gaming ecosystem tells a fascinating story. Understanding this history helps clarify why fully on-chain games exist, their significance, value, and target audience.

Let’s start with the Dark Forest ecosystem, including 0xPARC, Lattice, and the MUD on-chain game engine. On the Loot side, we had Loot—an NFT project consisting purely of text—which then spawned various other projects like DopeWar, Realms, and the Dojo on-chain game engine. As a result, both Dark Forest and Loot have given rise to today’s two dominant on-chain game engine ecosystems: MUD and Dojo. If we draw a Web2 analogy, I’d say MUD is more like Unity, while Dojo resembles Unreal Engine.

Dark Forest was originally built solo in 2020 by Brian Gu, then an undergraduate student also working at the Ethereum Foundation. During his research, he found zk (zero-knowledge) technology intriguing and decided to build a game using it—zk proved essential for this purpose.

In centralized games, there's a concept called "fog of war," where players can only see areas near their units on the map and must explore to discover enemy positions—similar to games like Command & Conquer. This is simple to implement in centralized systems but extremely difficult in decentralized environments because blockchains are inherently transparent. However, zk technology allows certain information to remain hidden. Using zk proofs, Brian implemented fog of war on-chain. The name "Dark Forest" itself was inspired by Liu Cixin’s *The Three-Body Problem*. He created a space-exploration-style game where spaceship locations were concealed via zk proofs. The game ran from late 2020 to early 2022, hosting a new round every six to eight weeks. Early rounds attracted just hundreds of players, growing to over a thousand later, with around 6,000–7,000 total unique addresses participating.

People found it cool and novel—a game format never seen before. Previously, without distinguishing between partial or full on-chain implementation, most people associated Web3 gaming solely with GameFi. But Dark Forest differed fundamentally—it had no economic model, no NFTs. It was simply a group of technically skilled individuals enjoying low-cost transactions. Because zk-based location hiding involves computational power, users could leverage GPU mining to gain competitive advantages—faster computation meant better performance. This technical edge cultivated a cult-like following among tech-savvy enthusiasts eager to outperform others.

Naturally, this made the game less accessible to average users. The initial interface was quite crude. I tried playing back in late 2020 and found it interesting at first, but gave up after half an hour. That reaction is common—how many of you who played early on had similar experiences?

Overall, it was a cutting-edge experiment rooted in Ethereum’s core, leveraging the latest zk innovations, with all logic written entirely on-chain. It inspired countless young talents not only to play but also to explore new applications of zk technology. By early 2022, although Dark Forest had developed a robust plugin ecosystem, the team realized its ceiling as a single game was limited. Seeing broader potential for zk, they founded 0xPARC—a research organization focused on zk technologies. Several notable zk projects emerged from this initiative. Those familiar with zk developments may already know 0xPARC; it originated from Dark Forest, led by founder Brian Gu. If I recall correctly, Brian Gu and Blur’s CEO Pacman were classmates at MIT, both born around 1998.

Initially, they aimed to dedicate 80% of their efforts to zk research and 20% to gaming. But later, realizing the promise of fully on-chain games, they shifted toward a 50/50 split. The gaming arm became Lattice, which developed the MUD game engine.

The idea for the MUD on-chain game engine came directly from Dark Forest. Since Dark Forest was coded directly on-chain, it was notoriously hard to develop and nearly impossible to modify afterward due to complex blockchain interactions. So the team decided to abstract Dark Forest’s experience into a reusable framework—or engine—leading to the creation of MUD.

They coined a powerful term for this vision: Autonomous World. Let me explain why this term works so well. “Autonomous” refers to the same A in DAO—building self-executing, decentralized infrastructure via blockchain. “World” doesn’t mean just our physical world—it can refer to any defined universe governed by specific rules. For example, Harry Potter’s universe or Romance of the Three Kingdoms each represent distinct worlds. Thus, any rule-bound, autonomously executing environment qualifies as an Autonomous World. It echoes earlier Metaverse concepts, though I believe within a year, “Autonomous World” might become synonymous with Metaverse. Regardless, it’s a brilliantly crafted term encompassing games, NFTs, DeFi, and DAOs. These worlds require governance and financial systems, aligning closely with Ethereum’s ambition to build network states. MUD developers further distinguished Autonomous Worlds (AW) from DeFi by categorizing DeFi as simple on-chain apps and AWs as complex on-chain applications.

One early example was OPCraft, officially launched by the team in November 2022. It was essentially a fork of Minecraft running on the OP chain, where every action—mining land, placing blocks—was recorded on-chain. But OPCraft introduced something fascinating: players could define their own rules. One player proposed a “land-grabbing” system where participants could pledge resources to join a nation, becoming citizens sharing collective rights over assets and territories—almost communist in nature. Many joined out of curiosity, and eventually, a real on-chain communist society formed. From a coding perspective, defining such rules was simple, but once adopted, it truly embodied the spirit of self-governance. A key milestone came in May when MUD V2 launched alongside a large hackathon, receiving 109 submissions—including eight teams from China.

Another official MUD project is Sky Strife, a real-time strategy game where players command troops to attack enemy bases. However, it requires four players online simultaneously. The team hosts weekly playtests during fixed two-hour windows, but outside those times, gathering four players is nearly impossible—highlighting a key issue: few people can actually engage with fully on-chain games yet.

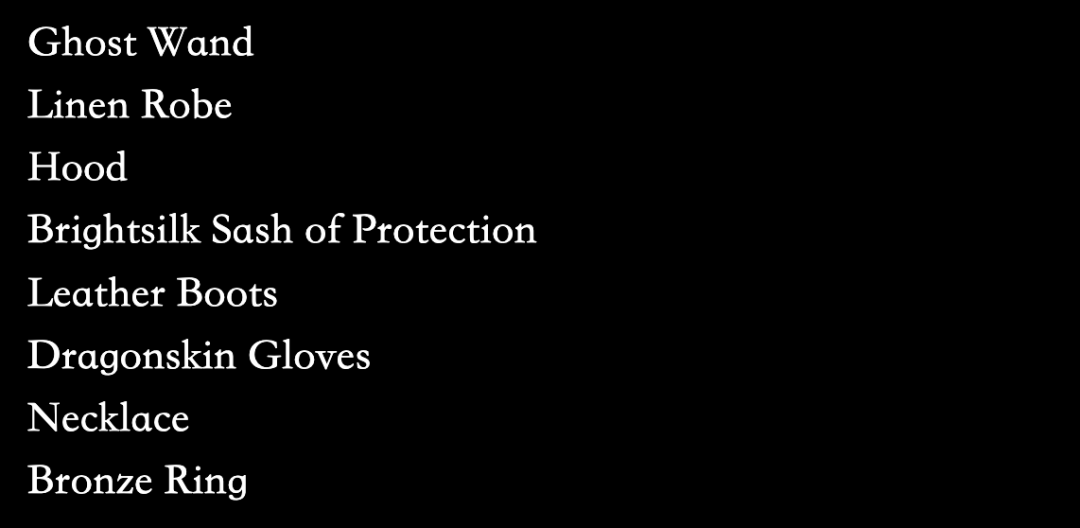

Loot launched slightly later, in late August 2021, as the first text-only NFT. At that point, the bull market had already lasted about two months. Prior to Loot, NFTs were mostly profile pictures (PFPs). Loot’s emergence brought fresh excitement to the industry. Its creators intentionally avoided visuals, leaving imagination open-ended. Each Loot NFT described eight pieces of equipment purely through text, sparking endless creative possibilities. Initially ignored, interest began on day three—I bought mine on day five.

Soon, developers began forking Loot, creating hundreds of derivative projects—most were scams that vanished within months. Yet about two dozen high-quality projects survived, forming Loot’s broader ecosystem. Four key NFTs stand out: first, standard Loot characters; second, Genesis Adventurers (premium-tier characters); third, Realms (large lands named after cities like Chang’an, Luoyang, Suzhou); fourth, Crypts and Caverns (small dungeon maps). This last one is particularly interesting—it aims to generate 8,000 randomized maps intended as universal templates for dungeon-based games worldwide, allowing infinite combinations.

These four form the backbone of the Loot ecosystem. Other innovative additions—like housing, portals, experience points—have expanded the world-building, collectively shaping something akin to a modern Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

Now imagine recreating a universe-level narrative like Romance of the Three Kingdoms today. Would you write a novel from scratch? Instead, launching a text-only NFT sparks imagination, inviting others to co-create content—potentially evolving into the next epic saga.

Dojo was jointly developed by Realm, Cartridge, and Briq on StarkNet. Observing MUD’s progress, they forked its codebase in late 2022. Since StarkNet isn't EVM-compatible, they rewrote it entirely. Dojo is natively ZK-compatible—once programmed, it automatically generates verifiable proofs for every step, a crucial feature of zk systems.

Its strengths extend beyond gaming—the developer community is highly loyal and active. Three flagship StarkNet projects include Kakarot (an EVM implementation), Madara (a sequencer), and Dojo (the game engine). Recently, StarkNet announced plans for application-specific chains, potentially integrating Madara and Dojo directly.

Another advantage: Dojo’s founding teams are more complete. Projects like Influence—a space-themed game—bring established teams and IPs into the Dojo ecosystem. While Dojo lags behind MUD by roughly two months in hosting hackathons, its core game teams are more mature. Most MUD projects stem from hackathon prototypes—higher quantity, lower quality—while Dojo focuses on depth and sustainability.

The first game built on Dojo was Loot Survivor—a lightweight arcade-style title designed as a proof of concept. Players control a Loot character, battle monsters, and upgrade gear. Being developed by original Loot contributors, it inherits the full Loot lore, including nations, races, generals, and strategists.

To summarize, using Dark Forest and Loot as case studies, we’ve traced the evolution of fully on-chain games. Below is the link to the presentation slides for further reading: Link

Wanwudao: Why did you get involved in fully on-chain games early on, and why stay committed?

For me, part of it was buying Loot early and spending years embedded in the community. But more importantly, I discovered how magical this space really is. To put it simply, fully on-chain games in 2023 resemble DeFi in 2019. CeFi and GameFi were semi-centralized experiments that gave people a taste of blockchain’s potential. But ultimately, both proved incomplete. Today, anyone building serious new projects naturally gravitates toward DeFi—we now clearly see its long-term promise.

StepN sparked massive hype but eventually faded. Yet without that cycle, people wouldn’t have realized fully on-chain games could be the next big breakthrough. In short, the shift from CeFi to DeFi mirrors the trajectory from GameFi to fully on-chain games.

Moreover, as mentioned earlier, fully on-chain games represent complex on-chain applications, whereas DeFi remains relatively simple. There’s a clear hierarchy here.

DeFi itself has two factions: projects funded by major U.S. VCs versus community-driven or fair-launch initiatives—often clashing fiercely. An interesting parallel exists in gaming: MUD feels like the former, deeply tied to Ethereum’s core ("Ethereum’s rightful heir"), while Dojo embodies the latter—community-born and driven.

Regarding Mask Network’s involvement in on-chain gaming, I initially just bought some Loot NFTs. Later, I accidentally invested in several StarkNet-based game projects, giving me early exposure to four of StarkNet’s five flagship initiatives. By late 2022, it became evident that StarkNet’s on-chain gaming scene showed strong promise. Mask is known for social products, but we’ve developed multiple social components and protocols, investing heavily in application layers relevant to Autonomous Worlds. Specifically, we integrate Mask’s protocol stack into these worlds. For instance, Next ID, one of our products, aggregates user identities across blockchains. In gaming, this enables use cases like cross-game progression: if you reach level 100 in one game, another game might let you start at level 30 to attract your participation—this is where Decentralized Identity (DID) adds value.

Second is Web3MQ, a communication-layer protocol supporting both person-to-person and machine-to-machine messaging. In gaming, it can serve as a cross-game notification system.

Third is MetaForo, a forum application offering fair grant voting platforms and tools for autonomous community events—essentially a governance solution.

Fourth is RSS3, which handles data feeds. A classic use case: just like your QQ Zone or Renren used to notify you when someone stole your vegetables, RSS3 can deliver similar in-game activity updates.

Together, these cover much of what we envision doing in on-chain gaming. Social and gaming are inseparable. I often say Mask aims to become the Tencent of Web3. With Autonomous Worlds emerging, that vision feels even more attainable. First, we focused on Tencent’s social side, then added its powerful investment arm (like Tencent Investment), and now incorporating Tencent Games—it all fits together logically.

Currently, very few projects in the on-chain gaming ecosystem have received traditional funding—they’re still in an extremely early phase, largely relying on grants.

Wanwudao: The narrative around fully on-chain games feels distant from Chinese-speaking communities. Any advice?

Fully on-chain isn’t just about storytelling—people genuinely want to build things. But storytelling still matters greatly in this space. MUD coined “Autonomous World,” and Loot itself is a massive narrative construct. It’s challenging for Chinese builders to create standalone narratives targeting Western audiences. A better path is to contribute within existing narratives. There are successful examples—MetaForo, the forum project I mentioned earlier, was one I helped connect. Deep immersion in communities reveals real opportunities.

I’ve also advised friends going to Paris to try reaching out directly—approach leaders in the on-chain space, engage with them, contribute to their projects, and get involved early.

The Loot ecosystem functions like a giant funnel. Initially, 300 or more speculative projects flooded in. About 30 took it seriously. After a year, most ran out of funds, leaving only a few passionate teams pushing forward. From this massive filter emerged truly exceptional projects. Though MUD doesn’t raise funds, I’d confidently assign it a $300M–$500M valuation today—with a clear path to $10B. Dojo may lag slightly but still merits a $200M–$300M valuation. Ultimately, this filtering process built an entire coherent universe—like a modern Romance of the Three Kingdoms built on Loot.

Personally, I see MUD’s lack of IP as a significant weakness. Yet its legitimacy ensures it attracts thousands of developers. Conversely, Dojo benefits from Loot’s strong core IP, drawing widespread attention. For Chinese teams, marketing to the West is a major hurdle—they seek Western validation and funding. Within the Loot ecosystem, early participation means that when the ecosystem grows, Western users come organically. Elsewhere, you'd need to build an entirely new IP convincing Americans it’s valuable.

Take StepN—it was essentially a Chinese IP, largely unknown to Americans. But Loot, despite periods of dormancy, surprised everyone by staying active. After two years, people returned to find actual progress being made—sparking organic Western advocacy. For Chinese founders, this solves a critical challenge.

Wanwudao: Who needs fully on-chain games the most right now?

Honestly, nobody truly needs them yet. This is clearly a space where we first build compelling prototypes, then figure out how to deliver them to users. If pressed, I’d say the most eager adopters are hungry VCs—they see this as a fresh investment frontier and are jumping in. Right now, projects are essentially serving each other as users. That’s the current reality.

Even Dark Forest struggled with user retention, partly explaining why the team pivoted from game development to building MUD—realizing the ceiling for any single game is low.

Wanwudao: What gameplay innovations could fully on-chain games introduce that are impossible in Web2.0?

One example I love: historically, numerous studios have released different versions of Romance of the Three Kingdoms games. In each, Cao Cao or Zhuge Liang are different characters. But in Web3 gaming, within the Loot ecosystem, there could be 50+ games set in the same universe—yet Cao Cao or Zhuge Liang would be represented by the same NFT across all titles. This demonstrates Loot’s groundbreaking potential. Back in the Web2.5 era, people talked about using PFP avatars like Bored Apes in games. But in practice, only the Bored Ape team built meaningful games—others failed to gain traction. The reason? Web2.5 games operate on isolated servers with little incentive to interoperate or build shared ecosystems. Only the original IP holder builds games around their characters.

Another promising moment will come when PFP mania fades and people actively seek new frontiers. They’ll realize fully on-chain gaming offers a more sophisticated narrative: the same Zhuge Liang appearing across countless games—that’s profoundly meaningful. The same applies to shared locations like Luoyang or Suzhou.

Wanwudao: What defines “fully on-chain”? Must everything be 100% on-chain, or can parts remain off-chain?

Looking at infrastructure, many are building application-chain frameworks to simplify launching custom chains. Over half modify OP Stack, making them technically centralized. In contrast, ZK-based chains require mining and can achieve true decentralization—projects like Wanwudao’s Opside are pursuing this path.

Currently, the community is quite tolerant regarding “full on-chain” definitions. As long as you follow general industry standards and use core on-chain components, minor centralized elements elsewhere won’t draw criticism.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News