On-chain Gaming Analysis: Bubble or a New Revolution? Exploring Core Advantages and Business Models

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

On-chain Gaming Analysis: Bubble or a New Revolution? Exploring Core Advantages and Business Models

Looking forward to new universes emerging on the path of fully on-chain games, in the open ocean.

Author:Fred @Dacongfred

Navigation

This article is 13,000 characters long and takes approximately 10–15 minutes to read.

I. Introduction: What Are On-Chain Games?

II. Why Do Humans Need On-Chain Games?

III. Current State of the On-Chain Gaming Industry

IV. Core Advantages of On-Chain Games

V. Challenges and Limitations of On-Chain Games

VI. Extended Thoughts on Business Models for On-Chain Games

VII. Conclusion

I. Introduction: What Are On-Chain Games?

Recently, Sky Strife’s Pass card craze reached 21,000 ETH, astonishing many players outside the on-chain gaming space about the magic of this sector. Since Pong debuted in 1972, the gaming industry has evolved rapidly—from classic 8-bit games like Super Mario and The Legend of Zelda to today's highly complex, socially connected online titles such as Fortnite and League of Legends. Games are no longer just simple entertainment; they now offer social interaction, competition, and immersive experiences that surpass our previous imaginations.

However, with the rise of blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies, the gaming industry is reshaping user experiences in unprecedented ways. From innovative projects like Axie Infinity that tightly integrate gameplay with crypto economies, to Stepn which centers around social innovation, blockchain games have increasingly been seen as a potential catalyst for mass crypto adoption. People are exploring new ways to merge games with blockchain—not just by putting assets on-chain, but also by moving more game elements onto the chain, leading to the emergence of fully on-chain games.

So what exactly distinguishes fully on-chain games from traditional games?

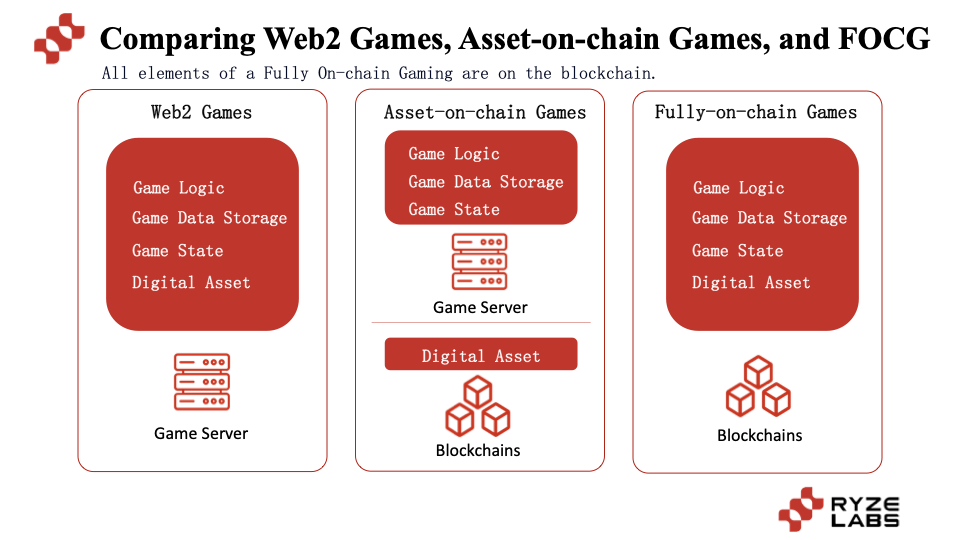

In traditional games, all game logic, data storage, digital assets, and game states are stored centrally within game companies. For example, when playing Honor of Kings, Genshin Impact, or DNF, all in-game content—including digital assets—is owned and controlled by centralized entities.

Later came asset-on-chain games (commonly referred to as Web2.5 games), such as Axie and Stepn, where digital assets are tokenized and placed on-chain. This allows players to own their assets and improves liquidity. However, if the game shuts down, these assets still risk losing value. Asset-on-chain games complement rather than replace traditional games—similar to how food delivery complements physical restaurants. Likewise, Web2.5 games face competition not only from other Web2.5 titles but also from traditional Web2 games.

Now, fully on-chain games—which have recently gained significant attention—move all interactions and game states onto the blockchain, including game logic, data storage, digital assets, and state management. Everything is handled by the blockchain, enabling truly decentralized gaming.

To help clarify, I summarize the key characteristics of on-chain games into four points:

- Authenticity of data sources is ensured by blockchain. Blockchain is no longer merely an auxiliary storage layer—it becomes the primary source of truth for game data. It goes beyond recording asset ownership to serving as the central repository for all critical game data. This leverages programmable blockchains to enable transparent data storage and permissionless interoperability.

- Game logic and rules are implemented via smart contracts. Any in-game action can be executed on-chain, ensuring traceability and security of game mechanics.

- Development follows open ecosystem principles. Game contracts and accessible clients are open-sourced, providing third-party developers broad creative freedom. They can build plugins, alternative clients, interoperable smart contracts, redeploy, customize, and share creations with the community.

- Decoupling between game and client. Closely related to the above three points, the essence of a truly crypto-native game is that it continues even if the original developer’s client disappears. This depends on permissionless data storage, permissionless execution of logic, and the community’s ability to interact directly with core smart contracts without relying on official interfaces—thus achieving true decentralization.

II. Why Do Humans Need On-Chain Games?

Before discussing why we need on-chain games, let's first understand the current state and operational model of the traditional gaming industry.

On-chain games are fundamentally still games. Understanding how traditional games operate is crucial and necessary for analyzing the future of on-chain games.

1. Current State of the Traditional Gaming Industry

As the gaming industry has grown, many outstanding Web2 games have emerged throughout our lives—whether FPS titles like Counter-Strike and CrossFire, RPGs like Dungeon & Fighter and Dragon Nest, MOBAs like League of Legends and Honor of Kings, or card games like Onmyoji and Hearthstone. These games have accompanied our generation, occupying a major part of our entertainment life.

According to Fortune Business Insights, the global gaming market was valued at $249.55 billion in 2022, expected to exceed $280 billion in 2023, and surpass $600 billion by 2030. In comparison, the global film and entertainment industry was worth $94.4 billion in 2022. As both are forms of leisure and cultural consumption, gaming plays a far more dominant role in economic development, offering deep commercialization and diverse genres—making it the crown jewel of the entertainment industry.

1) Why Do Humans Love Playing Games?

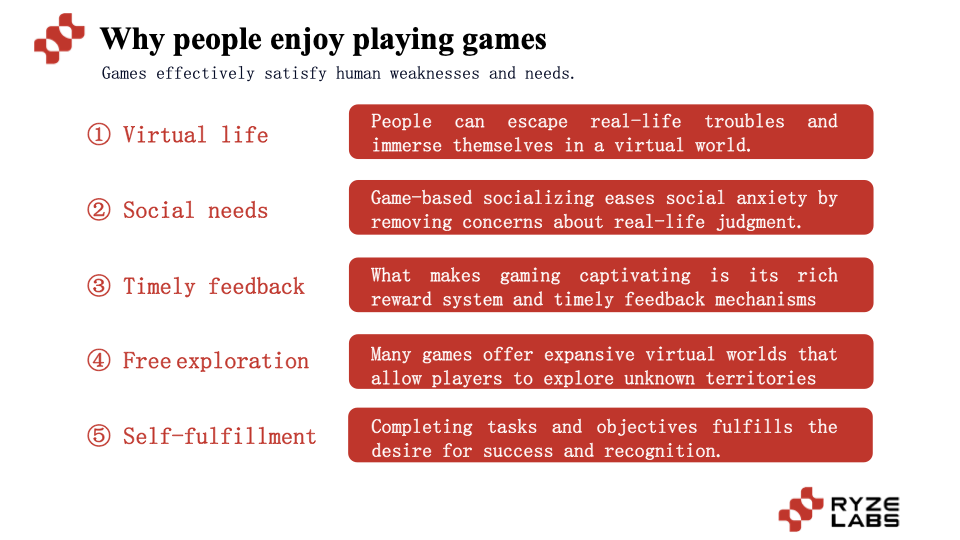

Statista data shows there are over 2.5 billion—and nearly 3 billion—global gamers. How do games attract over one-third of humanity? At its core, games skillfully satisfy multiple human desires and weaknesses:

- Escape reality and restart life: Games provide an escape from daily stress and challenges. Within them, people can leave behind real-world troubles and immerse themselves in virtual worlds, living a second life.

- Low-pressure socializing: Multiplayer games offer platforms for social interaction that are friendly to those with social anxiety. Players don’t have to worry about others’ judgments and can freely express themselves and form relationships.

- Immediate feedback and rewards: Unlike the daily grind of school or work, games are captivating because they offer rich reward systems and instant gratification. After effort, defeating monsters, leveling up, or completing challenges quickly yields new skills, unlocks levels, or grants items—motivating continued engagement.

- Low-cost exploration: Many games feature expansive virtual worlds where players explore unknown areas, interact with NPCs and others, and drive story progression—satisfying humanity’s innate desire for adventure. In contrast, real-world exploration is costly due to money, energy, time, and geography.

- Pursuit of achievement and self-actualization: Completing tasks and goals fulfills the desire for success and recognition. Whether through leaderboards or achievements, games make self-challenge and character growth easier to achieve.

By targeting one or more of these psychological aspects, games effectively meet diverse user needs and preferences, excelling in both audience reach and depth of immersion.

2) Current State and Development of Traditional Games

Next, let’s briefly examine the current landscape of the traditional gaming industry.

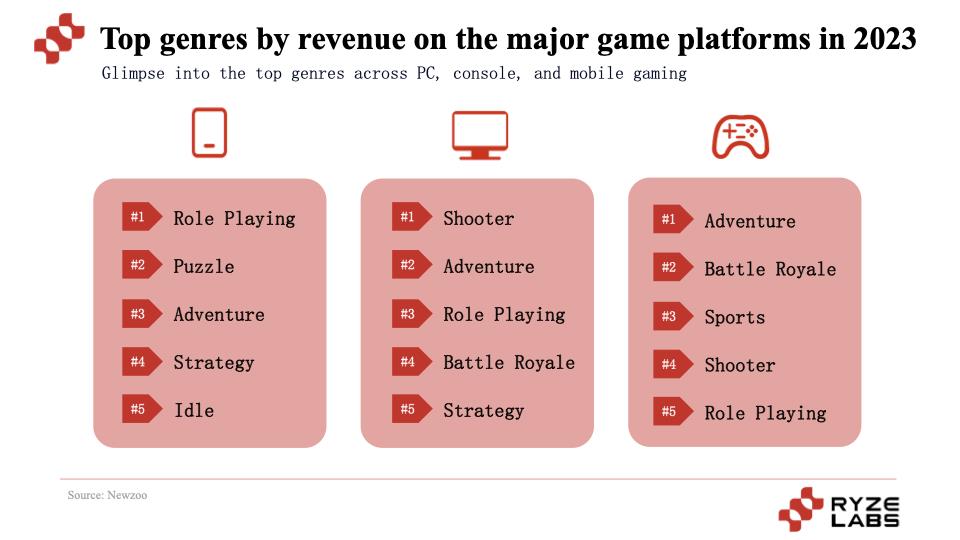

Traditional games generally fall into categories such as Shooter, Adventure, Role-Playing (RPG), Battle Royale, Strategy, Sports, Puzzle, Action, and Simulation.

Data from Newzoo indicates that RPG and adventure games perform well across PC, mobile, and console platforms, ranking among the top five. Shooters and Battle Royale games are especially popular on PC and consoles. On mobile, puzzle and idle games are particularly favored.

2. Challenges Facing the Traditional Gaming Industry

Despite its success, the traditional gaming industry faces two major challenges: game publishing restrictions due to licensing requirements, and high pre-launch costs resulting in slow returns and significant sunk costs.

1) Game Publishing Restricted by Licensing

A game license refers to a special permit issued by governments in certain countries or regions required to legally release a game. This system aims to regulate game content, ensuring compliance with local laws, culture, and values—particularly protecting minors from inappropriate material and maintaining social stability.

For instance, Germany enforces strict content review, especially regarding youth exposure; South Korea and Japan have government-led rating systems.

In China, the impact is even greater. A strict game licensing system is administered by the National Radio and Television Administration. Games cannot be released domestically without a license.

After issuing 87 licenses on July 22, 2021, the approval process stalled for months until resuming gradually in April 2022—with 45 licenses released that month, followed by additional batches in September and December. During the freeze from mid-2021 to April 2022, only large companies survived, while countless small and medium-sized studios collapsed. According to Tianyancha data, over 14,000 small-to-medium game companies (with registered capital under 10 million RMB) were dissolved between July and December 2021.

China, the world’s largest gaming market with over 500 million players, makes licensing a painful hurdle. Even after resumption, ongoing adjustments and tightening remain a constant threat—the sword of Damocles hanging over every project. Countless teams without funding have sighed in despair during long waits for approvals.

2) High Pre-Launch Costs and Significant Sunk Costs

In the Web2 game development model, upfront costs include human resources and infrastructure during development, plus idle time costs during licensing delays. Revenue only begins after licensing, launch, and monetization.

Most expenses occur early. If issues arise during development, licensing, or user acquisition, prior investments become sunk costs. For a mid-sized game, costs often reach several million dollars. Long development and launch cycles lead to delayed profitability and higher risks of failing to meet financial expectations.

3. Web2.5 Games Attempting to Break Through

Faced with these challenges, Web2.5 games pioneered solutions. First, they bypass domestic licensing constraints by targeting global audiences—any citizen of the world can play. Second, by launching NFTs and tokens during early testing phases, they generate revenue through market-making, drastically lowering financial barriers to entry.

This breakthrough gave rise to breakout hits like Axie and Stepn. Axie became so popular in Southeast Asia that many used it as a livelihood, earning more than average wages in the Philippines. Stepn’s “Move to Earn” model attracted non-Web3 users asking, “How does your running shoe work? I want to try too,” sparking mainstream interest in blockchain gaming. However, once Ponzi-like economic models collapsed, subsequent Web2.5 games failed to reignite similar momentum.

Builders began exploring new directions—one group pursuing AAA titles to compete with Web2 games, resulting in Web2.5 AAA games competing against both Web2.5 and Web2 counterparts. Another group shifted focus entirely, turning toward fully on-chain games to explore new possibilities and value propositions. In the emerging Web3 space, pioneers always seek uncharted paths forward.

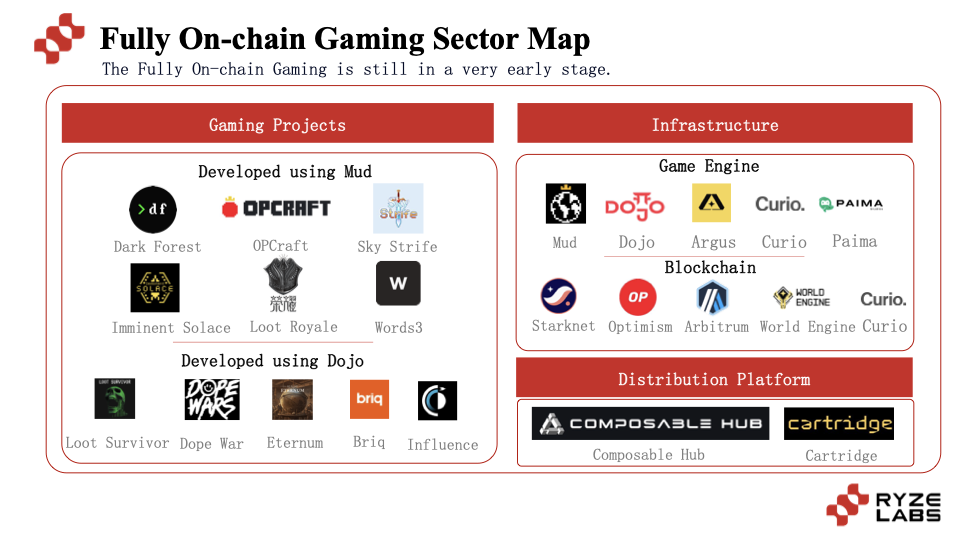

III. Analysis of the Current On-Chain Gaming Industry

The entire on-chain gaming space is still in its infancy, with both game projects and supporting infrastructure under active development. The on-chain gaming ecosystem can be broadly categorized into four segments: on-chain game projects, on-chain game engines, dedicated on-chain gaming chains, and distribution platforms.

1. On-Chain Game Projects

Current on-chain game projects are extremely early-stage. Below, I analyze several representative examples to illustrate the current state.

Notable titles include early pioneer Dark Forest, and newer entries like Loot Survivor, Sky Strife, Imminent Solace, and Loot Royale. Most playable projects remain in testing, with fewer than ten fully playable on-chain games available today. The genre is dominated by strategy games (SLG), though many new teams are experimenting with simulation and management genres.

Since most games are still under development or unplayable, I’ll focus on a few playable and distinctive ones.

1) Dark Forest

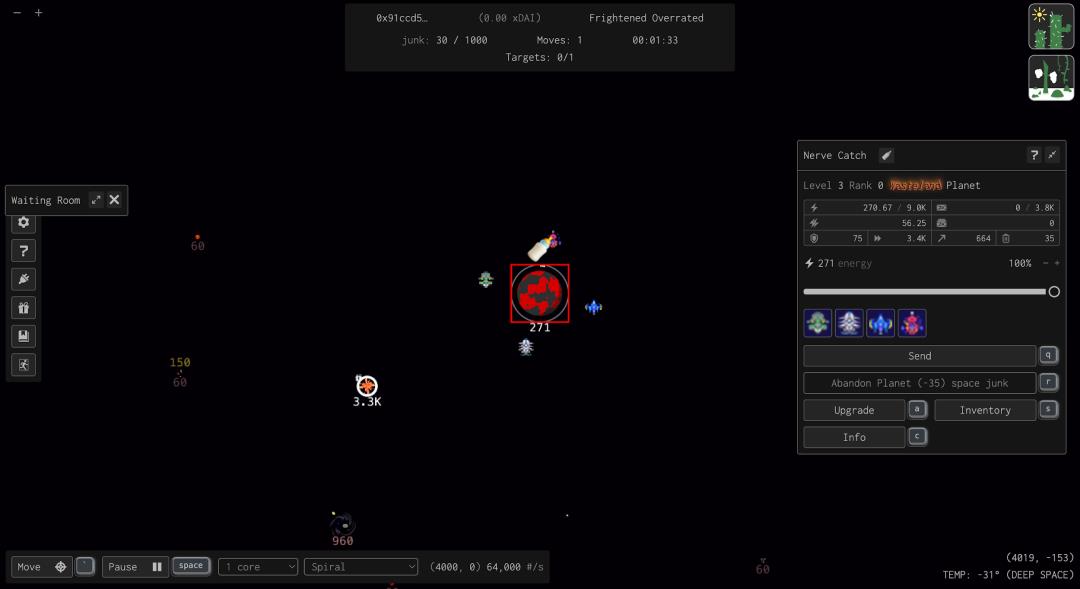

Let’s begin with Dark Forest, a flagship on-chain game. Simply put, Dark Forest is a decentralized strategy game built on Ethereum using zkSNARKs.

Developed by MIT graduate Brian Gu under the pseudonym Gubsheep, with contributions from Alan, Ivan, and Moe, Dark Forest was unfunded. However, the team’s new venture, Argus Labs, recently raised $10 million.

Dark Forest was one of the earliest incomplete-information games built on a decentralized system. As a space conquest strategy game, players start on their home planet and explore an infinite universe, discovering and capturing planets and resources to expand their empire.

Three standout features: Two were mentioned earlier—first, all game logic, data, and state are on-chain, preventing any single entity from controlling outcomes. Second, an open, composable game ecosystem: Open-sourcing enables permissionless interoperability. As an Ethereum smart contract, any address can interact with it, fostering a vibrant modding community and secondary ecosystems.

Examples include Project Sophon, which created a local library allowing users to run private games off-chain or on-chain; Ukrainian group Orden_GG building artifact marketplaces with liquidity pools; and Chinese DAO MarrowDAO|GuildW @marrowdao developing tools like artifact markets and GPU-based map generators. The UGC ecosystem is remarkably lively.

(Source: Official MarrowDAO Twitter)

Another major highlight is its use of zk-SNARKs for information hiding. In strategy games, full transparency would allow opponents to know your position, undermining strategic depth. Dark Forest uses zero-knowledge proofs so that most of the universe and other players remain hidden upon initial entry. Only when a player explores an area does it become visible. Each move sends a proof to the blockchain verifying validity without revealing coordinates.

After the official v0.6 Round 5 ended in February 2022, Dark Forest has not launched a new version. The game is currently in maintenance mode. To experience it, you can join community-run rounds—for example, creating a mini-universe via the Arena system developed by dfDAO.

(Source: Fred creating a new universe in dfDAO’s Arena system)

Overall, Dark Forest redefined the possibilities of Web3 gaming. Many praise it as a perfect intersection of gaming and cryptography, inspiring numerous subsequent on-chain projects. Historical player count exceeds 10,000.

But Dark Forest’s significance extends beyond gameplay. As the first widely recognized on-chain game, it serves as a symbolic beacon—a spiritual totem showing builders that open-ended composability and rich UGC ecosystems are possible, strengthening belief in the feasibility of “Autonomous Worlds.”

After creating Dark Forest, the team co-founded 0xPARC with others. One subproject, Lattice, found existing development tools prohibitively expensive and began the MUD project in 2022—to create a usable on-chain game engine based on the ECS framework, solving issues like contract-client synchronization, continuous updates, and cross-contract interoperability—significantly lowering development barriers and accelerating the entire sector. In many ways, Dark Forest is both a powerful symbol and a major catalyst for on-chain gaming.

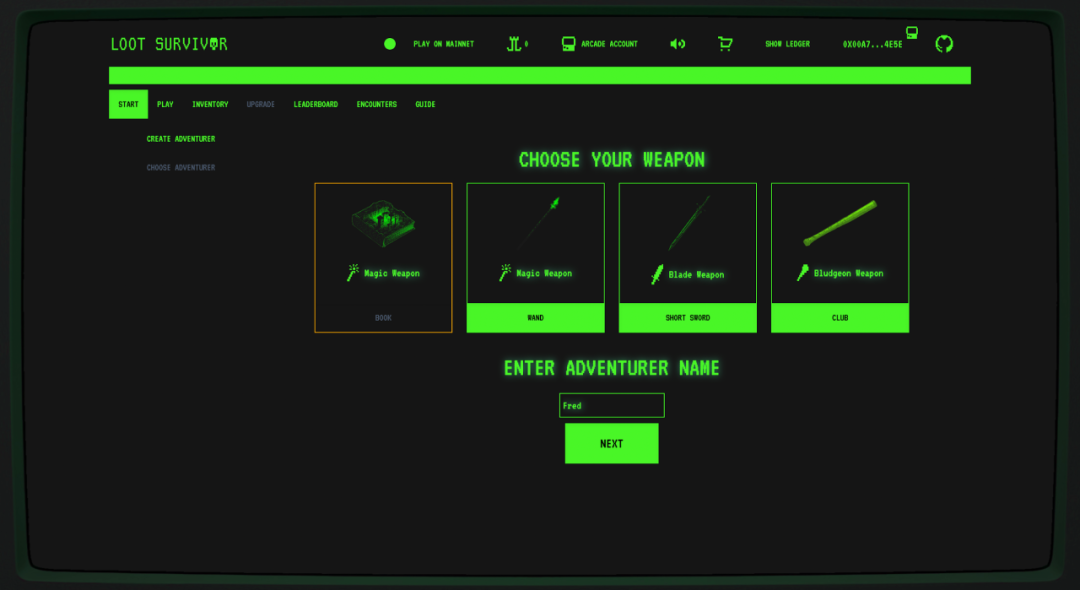

2) Loot Survivor

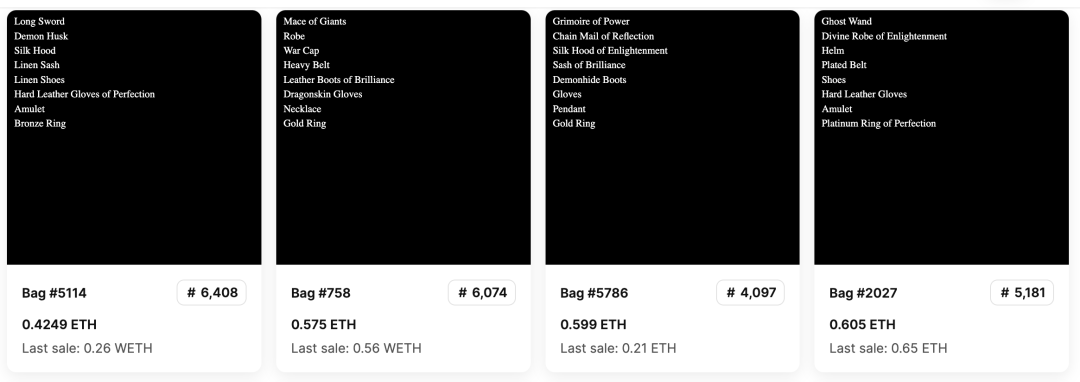

Next, consider Loot Survivor, a key title developed by the BibliothecaDAO team within the Loot ecosystem.

Loot was launched on August 28, 2021, by @Dom Hofmann. Unlike typical PFP NFTs like BAYC or CryptoPunks, each Loot NFT consists of plain text on a black background. Interpretation is completely open, inviting community-driven co-creation and spawning numerous derivative projects.

(Source: OpenSea)

Loot Realms, launched September 1, 2021, has driven Lootverse development, with key contributors @lordOfAFew and @TimshelXYZ shaping its foundational narrative, bringing storytelling to life through Eternum, the first Realms project.

As early as February 2022, the team introduced the core “Play 2 Die” concept, initially planned as an expansion called “Realms: Adventurers.” But during iteration, they decided to quickly launch a smaller, standalone on-chain game—giving birth to Loot Survivor.

Loot Survivor is a text-based dungeon crawler or Roguelike game. It debuted at the Fully On-Chain Games Summit in Lisbon on May 25 (also the author’s birthday) and received widespread attention.

Gameplay is simple: fight monsters via text commands until death, aiming to climb leaderboards through repeated attempts.

(Source: Fred’s gameplay screenshot and leaderboard ranking in Loot Survivor)

Overall, the game is lightweight and limited in playability. Its main contribution lies in continuing Loot’s legacy by adding gamified storytelling to the ecosystem. As a flagship project in the Dojo engine ecosystem, it also boosted confidence in both Dojo and Starknet.

3) Imminent Solace

Imminent Solace is a recent ZK-powered fog-of-war battle royale treasure hunt game built on the MUD engine by PTA DAO—a Chinese team deeply focused on on-chain games. It blends PvP looting, autonomous world exploration, and PoW-style resource mining, resembling Dark Forest but with improved usability and accessibility.

The ultimate goal is to create an EVE-like war simulation where players face real losses in resources and assets, requiring strategic decision-making.

Among recent on-chain games, Imminent Solace stands out for relatively high playability, with solid interaction and user experience.

(Source: Fred’s gameplay screenshot and ranking in Imminent Solace)

Other notable projects include Lattice’s internally developed Sky Strife, OPCraft, SmallBrain’s text game Word3, Web3 Werewolf Framed, battle royale Loot Royale, and pet-management game Genki Cats—all exploring the frontier of on-chain gaming, mostly still in testing. Playable games remain rare.

Research shows current on-chain games are almost exclusively web-based, with virtually no PC or mobile clients.

- One reason ties to the nature of on-chain games not needing dedicated clients. Since multiple frontends can connect to the same backend, developers prioritize fast MVP deployment. Web apps offer faster, cheaper development—making them the optimal, sometimes only, choice.

- Additionally, on-chain games are still in the proof-of-concept phase. Quickly delivering playable demos to validate value is paramount.

2. On-Chain Game Engines

Before diving in, let’s understand the essence of a game engine:

Simply put, it’s standing on the shoulders of giants. A game engine packages commonly used functionalities into reusable code, so developers don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

For example, in traditional engines like Unity or Unreal Engine, developers can leverage built-in physics simulations for explosions or collision responses—freeing them to focus on unique game content.

Similarly, on-chain game engines aim for the same efficiency. While traditional engines handle graphics rendering, physics, and networking, on-chain engines emphasize contract-client state sync, continuous updates, and cross-contract interoperability.

Current on-chain engines include MUD, Dojo, Argus, Curio, and Paima. Among them, MUD and Dojo dominate—representing EVM-compatible and Starknet ecosystems respectively. We’ll focus on these two.

MUD

Launched by Lattice in November 2022, MUD was the first fully on-chain game engine. Lattice and Dark Forest are both part of 0xPARC. As the earliest engine, MUD now hosts the largest developer community. Beyond Dark Forest, it powers OPCraft, Sky Strife, Word3, and recently Imminent Solace—making it the most widely adopted on-chain engine.

Dojo

Born in the Starknet ecosystem, Dojo started as a port of MUD for Cairo language and officially launched in February 2023. As core developer tarrence.eth explained, the team believed Cairo offered advantages over Solidity in recursive proofs and incremental verification.

Yet another core developer, Loaf, noted that the motivation wasn't that MUD was insufficient—but that he wanted to build an ECS system on Starknet, so he forked MUD. Similarly, other Layer1/Layer2 chains like Move and Flow are now forking their own engines—to foster native ecosystems by providing foundational infrastructure for builders.

Backed by the Loot IP, the Dojo ecosystem includes strong projects like Loot Survivor and Loot Realms: Eternum. Others like Dope Wars and Influence also show promise.

Just as traditional engines fueled industry growth, the rise of on-chain gaming owes much to these engines lowering development costs. MUD and Dojo accelerated the sector, fueling hackathons like ETH AW, Pragma Cairo 1.0, and Lambda zkWeek in May, June, and July.

3. On-Chain Gaming Chains

Compared to the popular game-specific chains in the Web2.5 era, current on-chain game projects prefer general-purpose Layer2s like Arbitrum Nova, Optimism, and Starknet.

The core reason: the target audience for earlier game-specific chains—players interested in Web2.5 games and AAA-like titles—are less drawn to the simpler, rougher aesthetics of current on-chain games. Thus, those so-called game-specific chains hold little appeal for today’s on-chain developers.

Moreover, CaptainZ highlighted a fundamental conflict: blockchain’s push-based model vs. games’ loop-based architecture.

Many blockchains are event-driven—state updates only occur upon new transactions. This aligns well with sectors like DeFi: trading on Uniswap or posting on Twitter triggers passive, event-driven actions.

But most traditional games are loop-based (except turn-based or asynchronous ones). The game loop actively processes inputs, updates state, and renders visuals—running dozens or hundreds of ticks per second to maintain continuity.

This creates a natural mismatch. To resolve it, some teams are building specialized on-chain gaming chains—also known as ticking chains.

For example, Argus is building a new Layer2 on Polaris (an EVM module compatible with Cosmos SDK)—a ticking chain with precompiled tick functions, named World Engine. Curio is similarly building on OPStack with precompiled tick support.

Though still in development, these purpose-built rollups could significantly boost the on-chain gaming space.

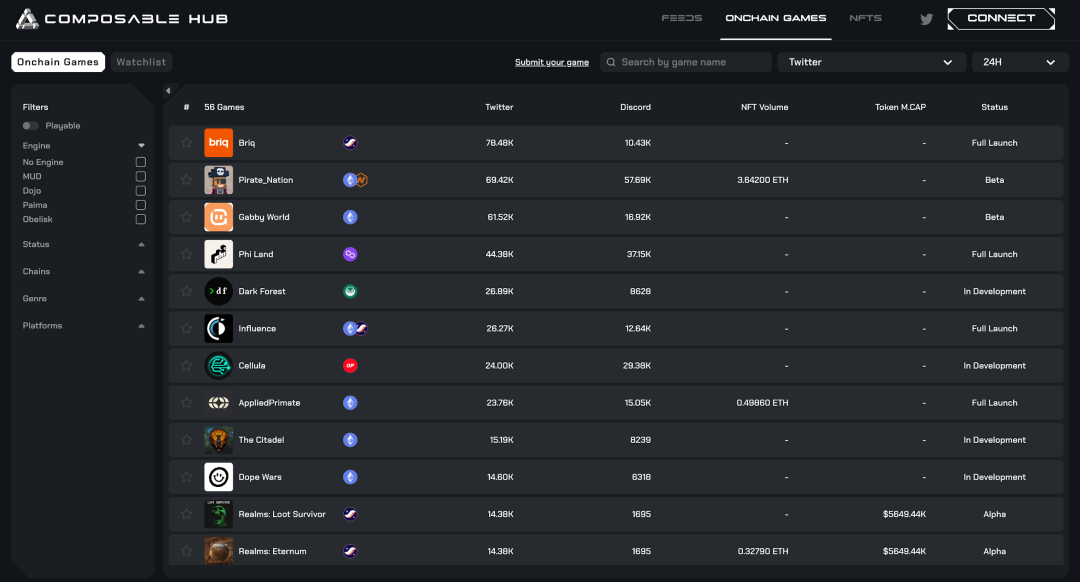

4. On-Chain Game Aggregators / Distribution Platforms

Finally, let’s cover the nascent stage of on-chain game aggregators and distribution platforms. Given the early state of the sector, playable on-chain games are extremely scarce. According to Composable Hub, fewer than 30 such games exist—even counting alpha, beta, and live versions.

Currently, players discover on-chain games mainly through word-of-mouth or niche communities—unlike mature sectors like DeFi or GameFi, which benefit from numerous aggregators.

Two main platforms specialize in on-chain game aggregation: Composable Hub and Cartridge.

Composable Hub

Composable Hub is a platform by Composable Labs focused on aggregating on-chain games. The company also runs Klick (a Web2.5 GameFi aggregator) and Lino Swap (an NFT DEX).

Composable Hub currently lists 56 on-chain games: 14 live, 12 in testing, and 30 still in development.

(Source: Composable Hub)

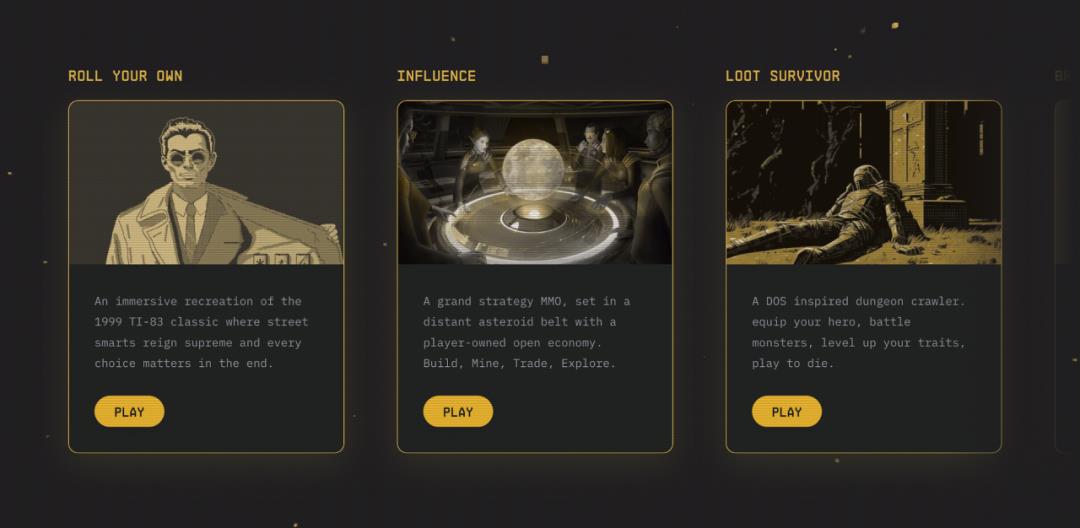

Cartridge

Cartridge is a Starkware-backed on-chain game aggregator aiming to become the “Web3 Steam.” It currently hosts five Starknet games: Dope Wars-Roll Your Own, Influence, Loot Survivor, Briq, and Frens Land.

Cartridge also actively supports Dope Wars-Roll Your Own and is a core contributor to the Dojo engine.

(Source: Cartridge)

IV. Core Advantages of On-Chain Games

In summary, on-chain games enhance fairness by placing all logic, state, data, and assets on-chain. With open-source contracts and clients, they empower third-party developers with vast autonomy—enabling new rules and gameplay modes created by the community.

This openness transforms gaming from a binary structure—developers as providers, players as consumers—into a model where every player can become a builder and creator.

1. From PGR to UGR: Giving Everyone God-Like Powers

In traditional games, all content comes from official developers. Whether playing Honor of Kings, Genshin Impact, Fortnite, or Overwatch, we exist in a PGC (Professional Generated Content) model as participants. We may engage in UGC (User Generated Content) like fan art or fiction, but never touch core mechanics.

Such creativity doesn’t extend to rules or gameplay—we remain consumers, not creators, bound by PGR (Professional Generated Rules). For creatively inclined players, this is a constraint. Disillusioned in the real world, humans yearn for god-like power—through novels, films, or games.

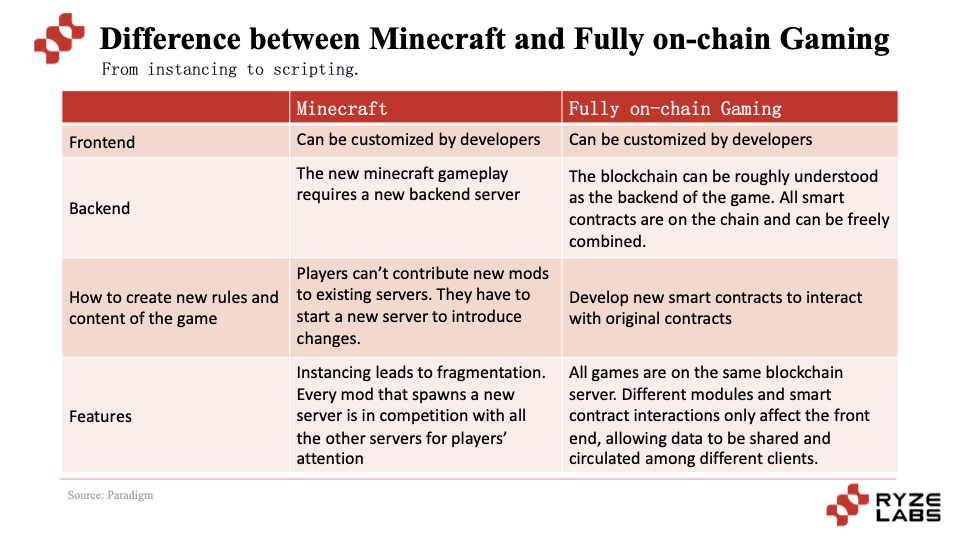

Most traditional games avoid openness due to business, security, and stability concerns. Yet some have shifted toward openness, allowing mods and custom content. Minecraft is the prime example—letting players host servers with custom modes, rules, and gameplay, spawning variants like Minecraft battle royales or even virtual graduation ceremonies during the pandemic.

However, these servers are isolated silos competing for attention. Data earned in one server doesn’t carry over. This UGR is crippled—an individual universe, not a shared one.

Minecraft requires new servers for new modes. On-chain games differ by sharing the same backend—different mods and contracts affect only the frontend, enabling shared, interoperable data across clients.

Because on-chain game logic and rules are public and permissionlessly interoperable, players can freely build new features and experiences—not in isolation. This creative freedom greatly enriches gameplay: markets, embedded games, custom clients—diversifying the experience and enabling a shift from PGR to UGR.

This reminds me of the fictional world of “Jiuzhou” co-created decades ago by Chinese writers like Jiangnan, Jin Hezai, and Dajiao—built through collaborative storytelling, evolving into literature, film, and games.

Analogous to life, on-chain games resemble playing cards. Cards have fixed suits and numbers, yet humans invented countless variations—Dou Dizhu, Texas Hold’em, Tractor, Level-Up, Xinzhihuang, Zha Jin Hua—showcasing rule diversity and flexibility. On-chain games work similarly: open creation and interoperability allow players to build diverse experiences atop shared foundations. In traditional games, everyone is a consumer. In on-chain games, anyone can be a rule-maker.

Thus, the strength of on-chain games lies in openness and permissiveness—granting players greater creativity and freedom to shape rules and content, forming a diverse, personalized, and vibrant ecosystem.

2. Fairness and Transparency: An Unmanipulated Gaming Environment

Another major advantage is transparency—since all game logic and rules are on-chain.

This is especially crucial for gambling and betting games.

Like in the hit movie "No More Bets," casino apps are often manipulated by centralized operators—results aren’t random but predetermined. For card games like poker or Zha Jin Hua, opaque processes turn countless players into victims—exactly why monetized Web2 gambling games are widely criticized.

On-chain games solve this by making rules publicly verifiable. Combined with cryptographic techniques (e.g., ZK-SNARKs in fog-of-war games like Dark Forest and Imminent Solace), they deliver fairness unattainable in Web2 or Web2.5 games—especially for genres demanding integrity.

V. Challenges and Limitations of On-Chain Games

Despite improving infrastructure and growing momentum, on-chain games still face many limitations and challenges:

1. Poor User Experience

There’s a consensus among players: current on-chain games are far less playable than Web2 or Web2.5 titles. Most have primitive or crude graphics, and suffer from four key UX hurdles:

1) Hard to Start: Difficulty Matching with Other Players

Multiplayer PvP games often require four players, but on-chain games typically have tiny player bases—sometimes fewer than ten concurrent users. Without matchmaking systems, multiplayer games rely on manual room creation and invites, easily discouraging newcomers.

2) “Halal” or Not: High Artificial Barriers

Beyond gameplay, many games impose artificial barriers—fixed play times, entry fees, or mandatory token/NFT purchases—increasing cost and friction.

Some developers uphold indie ideals, believing paying for games is “pure.” But unlike Web2 indies that offer genuine innovation or quality, most on-chain games lack compelling playability. Why pay to play something you wouldn’t glance at in Web2? This reinforces stereotypes of on-chain games being insular echo chambers. Beyond a few believers, how many truly want to play? Most testers participate out of passion—such pay-to-play models feel alienating.

3) Poor Experience: Frequent Bugs

On-chain games demand faith—and patience.

From PC to mobile, games trend toward convenience.

Yet in on-chain games, players often encounter bugs—page refreshes, sudden errors—making it hard for the impatient to complete even a basic session.

4) More Hype Than Substance: Grand Vision, Low Playability

Most projects boast big narratives but deliver minimal playability—often harder to enjoy than 10-year-old browser games. Hopefully, with better infrastructure and more builders, on-chain games will close the gap with Web2 titles.

2. Game Genre Limitations

Due to current blockchain performance and infrastructure limits, not all game genres suit on-chain models.

Current on-chain games are mostly SLG (strategy) types—less dependent on real-time updates. RPGs, AVGs, ACTs, and MOBAs demand frequent, instantaneous state changes. With today’s blockchain speeds, sustaining such responsiveness remains challenging—making them poorly suited for full on-chain implementation.

Today’s on-chain games follow two paths: minimalist designs with playable MVPs—simulation, pet-raising, tower defense—or grand narrative-driven open worlds. But due to genre constraints, progress remains limited. Creating the next Axie or Stepn requires further exploration.

3. Real Need or Fake Need?

The biggest challenge and debate centers on whether the demand is genuine.

Take the two core advantages:

1) The PGR-to-UGR shift: Web2 open games like Minecraft already offer this. And is cross-client data interoperability really needed? Does a mount, level 90 status, or flying wings from an RPG need to transfer to a MOBA? Necessity remains questionable.

2) Fairness and transparency: Mainly relevant for gambling games. But online gamblers (~120 million in 2023) are vastly outnumbered by offline ones (~4.2 billion annually)—a low ceiling. Moreover, serious gamblers prioritize deposit/withdrawal ease over fairness. Compared to seamless fiat systems, Web3’s infrastructure gaps make this a major weakness.

If future genres can effectively leverage UGR and fairness, they might solve real gamer needs and attract broader participation. But for now, the path remains long and uncertain.

4. Fully Decentralized Games Aren’t Necessarily Fun—They Might Cause Chaos

Like a coin’s two sides, openness brings chaos. Human nature leans toward laziness. Players who prefer consumption over creation—accustomed to PGR models—prioritize fun above all.

True game designers rarely relinquish control. Average users vary in skill—ordinary players designing games may compromise balance and enjoyment.

Should game design be left to professionals or given to everyone? This is a profound question. Balancing democracy and elitism is difficult.

For on-chain game teams, it’s vital to maintain engaging core mechanics while leaving room for player-driven innovation—striking a delicate balance. Otherwise, games risk becoming overly centralized or too hollow to inspire community creation.

Teams must act as the “initial god”—crafting solid core gameplay and incentivizing players to co-create and enrich the world.

VI. Extended Thoughts on Business Models for On-Chane Games

Finally, let’s discuss business models for on-chain games—an important topic for both builders and investors.

First, consider traditional gaming’s business evolution—a journey shaped by tech advances, market shifts, and changing player demands:

- 1970s: Coin-operated arcade games like Pac-Man and Galaga charged per play, marking the earliest consumer-facing electronic games.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News