Meng Yan: After a trip to Africa, I now believe blockchain opportunities lie in the Indo-Pacific region

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Meng Yan: After a trip to Africa, I now believe blockchain opportunities lie in the Indo-Pacific region

Developing countries in Southeast Asia and Africa are not content with merely "catching up" in digital economic infrastructure; they do not wish to repeat the paths taken by the United States and China, but instead aim to leap directly into the blockchain-based Digital Economy 3.0 era.

Author: Meng Yan, Co-founder of Solv

From June 20 to 24, I was invited by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) to attend the inaugural Inclusive FinTech Forum held in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. I also made brief stops in Singapore and Dubai on my way there and back, spending a full two weeks traveling roughly along the northern arc of the Indo-Pacific region.

Before this trip, I had heard analyses suggesting that real-world blockchain applications—or rather, blockchain’s true opportunities—lie not in the U.S., Europe, or East Asia, but in Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, all around the Indian Ocean, collectively known as the Indo-Pacific region. While these arguments sounded logical, they remained hearsay to me, and I remained somewhat skeptical.

As the saying goes, "Traveling ten thousand miles beats reading ten thousand books." After experiencing it firsthand, I gained some direct impressions and developed deeper thoughts about blockchain's prospects in the Indo-Pacific region, which I’d like to share here. Of course, a mere two-week journey provides only superficial observations; no profound conclusions can be drawn. This article is offered merely for industry reference, and I welcome critique and alternative viewpoints.

1. Background

I was able to participate in the Inclusive FinTech Forum because Solv Protocol and our Australian-incubated ecosystem partner, Unizon Blockchain Technology (UBT), were invited by MAS to sponsor and take part in the event.

Representing Solv, I traveled from Melbourne, Australia, via Singapore and Dubai, arriving in Kigali, Rwanda, early on June 20.

During my time in Kigali, together with UBT representatives Belle Lou and Chong Ren, I co-chaired a breakout session on ERC-3525 applications in real-world asset (RWA) industries, delivered an exhibition speech, participated in two roundtable discussions, engaged in exchanges with the Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Rwanda, MAS’s Chief FinTech Officer, central bank officials from Ghana, Cambodia, Nigeria, Kenya, and other countries, as well as FinTech entrepreneurs. I visited the Kigali Genocide Memorial and spent a full day touring Akagera National Park and rural areas of Rwanda—an experience that proved highly rewarding.

Welcome ceremony at the Inclusive FinTech Forum

The Inclusive FinTech Forum is a government-industry summit initiated by Singapore’s MAS. In my view, its main purpose is to bring together financial officials, bankers, and entrepreneurs from developing countries to explore how financial technology innovation can deliver financial services to small and medium enterprises and ordinary citizens, enabling rapid and sustainable economic development.

Participants included not only host country Rwanda and organizer MAS, but mainly came from Southeast and South Asian nations such as India, the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Cambodia, and Bangladesh, as well as African countries—especially sub-Saharan African nations including Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda, Ghana, and South Africa—nearly all of which sent representatives. The forum’s impressive scale at its first edition owes much to the strong reputations of Singapore and Rwanda.

Despite its small size and lack of natural resources, Singapore has grown into a high-income advanced economy within decades, earning admiration across Indo-Pacific developing nations for its achievements in financial services, social governance, and tech industries, becoming a model they aspire to emulate. Meanwhile, after the 1994 genocide tragedy, Rwanda rose from the ashes, transforming itself in under thirty years into a model of governance and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. With both governments collaborating, the forum naturally holds strong appeal.

The conference attracted 2,500 participants from dozens of countries

2. Impressions of Rwanda

This trip marked my first visit to Africa—and surprisingly, my very first destination was Rwanda. Years ago while working at IBM, I was once considered for a business trip to Kenya to support an African expansion strategy, but it never materialized. At the time, based on general knowledge, I assumed that if I ever went to Africa, it would likely be to more "developed" places like Kenya or Nigeria—not Rwanda.

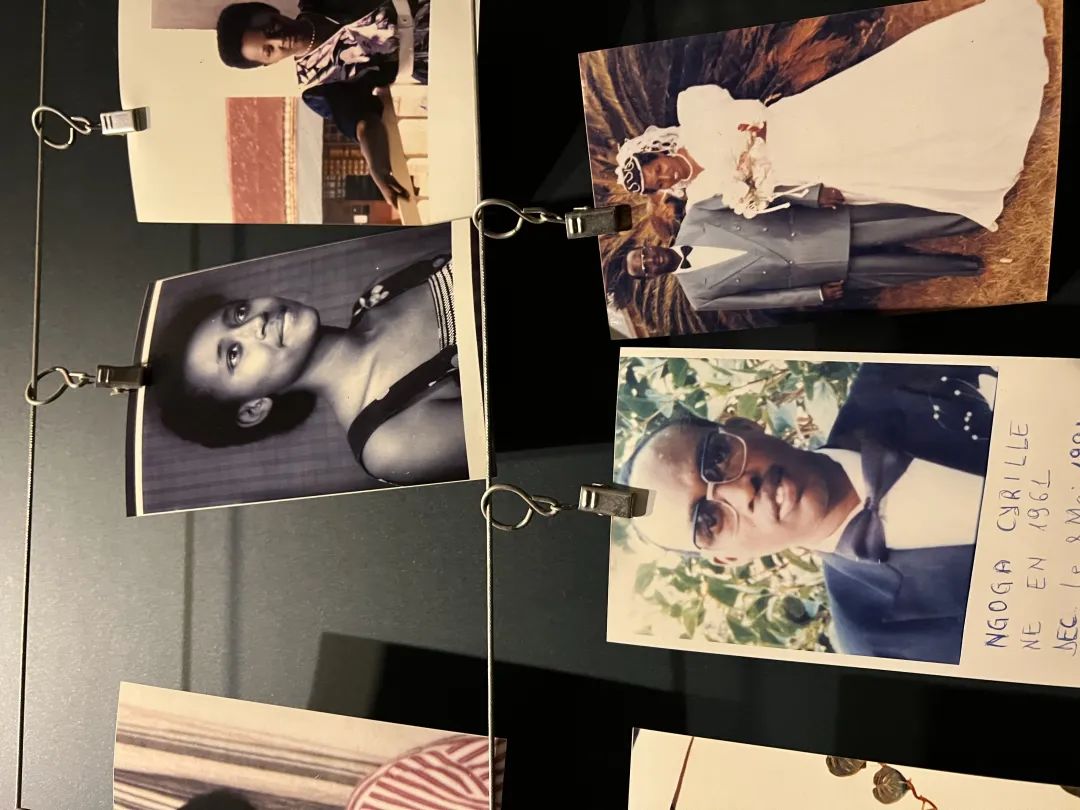

Like most people, my prior impression of Rwanda was defined solely by the horrific genocide nearly three decades ago. The Rwandan genocide occurred between April and July 1994, but news of it reached China en masse in July, so my memory of the event is intertwined with that year’s FIFA World Cup. I recall TV news switching abruptly from exciting World Cup highlights to graphic images of massacre victims—one moment Maradona taking banned substances, Baggio missing a penalty kick, the U.S. launching its Information Superhighway initiative, and the next, reports of over a million people slaughtered in ethnic violence. It felt surreal—how could such barbaric racial massacres still happen on the brink of the 21st century? How could such a thing occur in the modern world? Years later, after watching the film *Hotel Rwanda*, I learned more about the causes, but still never imagined I’d one day set foot in Rwanda.

But before this trip, many told me Rwanda is one of Africa’s greatest success stories over the past two decades—often dubbed “Africa’s Switzerland” or “Africa’s Singapore.” Yet checking Wikipedia, I saw it remains a poor country with GDP per capita below $1,000—how could it be compared to Switzerland or Singapore?

Spending four days in Rwanda profoundly changed my perspective. I began to understand why outsiders praise it so highly. A full account of my impressions would require thousands of words, so here I’ll highlight just a few points relevant to this article.

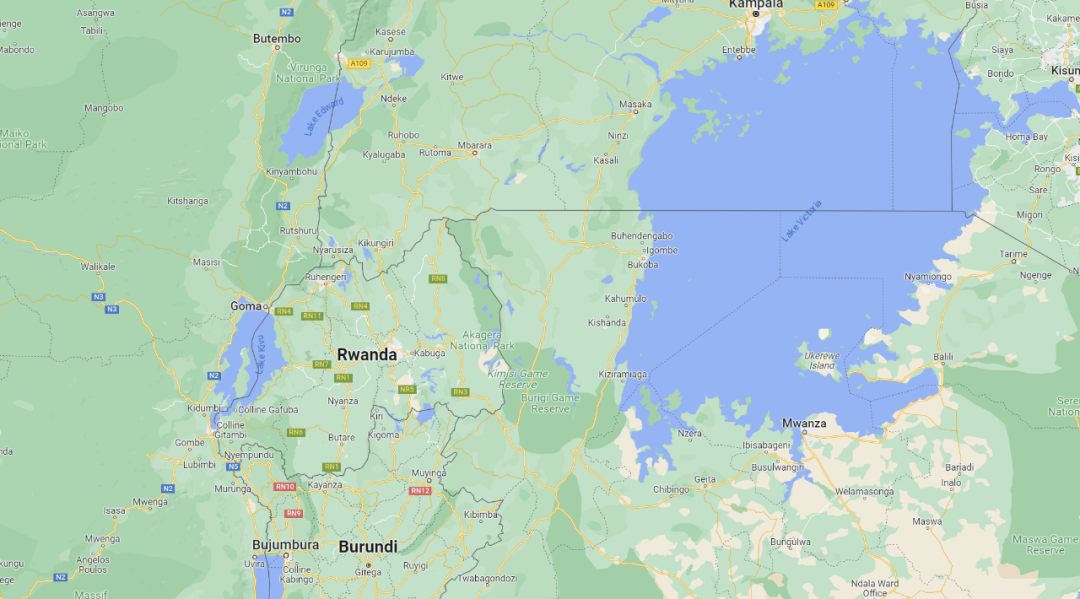

Natural Conditions: Rwanda covers 27,000 square kilometers, mountainous and nicknamed “Land of a Thousand Hills.” Our strongest impression was its excellent climate. Though located directly on the equator, during summer the temperature ranges from teens to low twenties Celsius, with humidity around 40%, making it dry, cool, and extremely comfortable—sharply contrasting humid Singapore and scorching Dubai. Rwanda experiences only dry and rainy seasons: the dry season is generally pleasant and cool; the rainy season warm and moist. Climatically, it is exceptionally livable. We learned similar conditions exist in neighboring Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania due to climate regulation by the massive Lake Victoria nearby—challenging typical perceptions of equatorial regions.

Rwanda lies southwest of Africa’s second-largest freshwater lake, Lake Victoria, right on the equator

Population: Rwanda had 7 million people during the genocide. Over three months, over a million were killed and another million displaced, resulting in a loss of over 2 million people in just months. But since the war ended, national reconciliation, political stability, and economic growth have driven rapid population recovery. Today, Rwanda has 13 million people and has become a key immigration destination for neighboring countries.

The genocide was perpetrated by the Hutu against the Tutsi. Since then, the Rwandan government no longer recognizes ethnic distinctions—everyone is simply Rwandan. Physically, Rwandans do have distinctive features: tall stature is common, with many men exceeding 190 cm, slender builds, sharp facial features, lighter skin than southern Africans, and many strikingly handsome individuals.

Photos of some victims at the Kigali Genocide Memorial

Economy and Infrastructure: Rwanda is a landlocked, mountainous country with limited natural resources. Its main exports are coffee and tea. With a GDP per capita of around $900—roughly equivalent to China’s level in 2000—its actual living standards and infrastructure resemble China’s early 1990s. Road quality is decent but narrow, often just two lanes, where one slow vehicle can block traffic for long periods. During my stay, we experienced one power outage—unclear whether isolated or routine. Urban housing resembles Chinese tier-four or five towns; rural areas still feature many mud houses. However, the government has launched a program to build free, high-quality housing for the poor. Basic healthcare is universally accessible. There are many cars, not bad brands either, but fuel quality is poor, filling the air with pungent exhaust fumes—evoking memories of 1990s China.

Kigali CBD, capital of Rwanda

Government-built free housing for low-income residents (under construction)

Security and Civilization Level: Compared to its economic status, Rwanda’s safety and civility are astonishingly high. Security is excellent—a foreigner walking alone at night faces no safety concerns. People are generally warm, friendly, and courteous. When we paused at crosswalks, vehicles stopped to let us pass; children waved enthusiastically upon seeing foreigners. We noticed numerous armed police and military patrolling streets, indicating this security stems from active governance. Rwanda’s public safety has become a national brand—a unique advantage even neighboring countries lack.

Politics: Rwanda’s current president, Paul Kagame, led the Rwandan Patriotic Front from exile back into Rwanda in 1994, overthrowing the interim regime responsible for the genocide and rescuing the people. He served as Vice President before becoming President in 2000, now ruling continuously for 23 years. According to Rwanda’s constitution, he may remain in office until at least 2034. Under Kagame, Rwanda enjoys political stability, rapid economic growth, rising population, and strengthened social security—having solved food and shelter issues, achieved universal healthcare, and actively addressing housing for all. Consequently, President Kagame enjoys immense popularity among the populace.

A photo of President Paul Kagame hanging in a travel agency

Language: Rwandans typically speak multiple languages. Besides local dialects, many speak French, English, and Swahili. Schools mandate both English and French. Due to long-term Belgian colonization, French is preferred, so English pronunciation often carries a strong French accent. However, their expression is fluent, using sophisticated vocabulary and sentence structures. Once accustomed to their accent, communication in English flows smoothly.

Media, Communications, and Financial Infrastructure: Televisions aren’t yet widespread in Rwandan households, desktop computers are rare, but nearly every adult owns a smartphone. The most popular local brand is Tecno, a Chinese phone maker dominant in Africa, followed by Samsung. Apple iPhones are used only by a few wealthy individuals. The currency is the Rwandan franc, trading at about 1,160 to the dollar, depreciating several percentage points annually.

Cash remains the primary payment method, followed by mobile payments. Places accepting cards only may pose difficulties. ATMs exist but need wider deployment.

The leading mobile payment platform is MoMo, with competitors like BK from Kigali Bank. Kenya’s famous M-Pesa system is also popular in Rwanda. 4G coverage is near-universal, with free Wi-Fi widely available in public spaces. From personal experience, internet speed is good.

Mobile payment app ads on Kigali streets

These are my initial impressions of Rwanda. Though seemingly off-topic, understanding this social context is essential to grasp the main arguments below. Naturally, with limited time, biases and inaccuracies may exist—readers with deeper insights are welcome to correct them.

3. Leapfrogging into Blockchain

Honestly, before attending, I thought our blockchain-based ERC-3525 digital note technology might be too advanced for these Indo-Pacific nations. I figured they should probably focus first on普及 electronic payments. But unexpectedly, our solution received enthusiastic responses.

During the conference, I presented our pilot project for the Reserve Bank of Australia’s CBDC digital invoice system. A Rwandan entrepreneur immediately raised his hand, declaring, “This is exactly what Africa needs.” A Nigerian tech VC directly requested contact to discuss investment interest.

An official from Ghana’s central bank asked whether ERC-3525 technology could help African nations solve interoperability issues among their respective central bank digital currencies. A representative from Cambodia’s central bank innovation department invited us to discuss applying ERC-3525 in cross-border supply chains. These reactions surprised and intrigued me: Why are Indo-Pacific countries so eager for such cutting-edge technology?

After discussing with knowledgeable African friends and Singaporeans familiar with Indo-Pacific markets, I reached a crucial conclusion: Late-developing countries in Southeast Asia and Africa don’t want to merely “catch up” in digital economy infrastructure. They don’t wish to retrace the paths of the U.S. or China, but instead aim to leap directly into era 3.0—the blockchain-based digital economy.

Why do they hold such aspirations?

If we consider the U.S.-pioneered digital finance system—based on POS terminals, credit cards, and interbank clearing networks—as FinTech 1.0, and China’s flourishing mobile internet payment ecosystem as FinTech 2.0, then most Indo-Pacific nations are still at very early stages of both 1.0 and 2.0. As mentioned earlier regarding Rwanda, many stores lack POS machines, bank card penetration is low, and cash dominates transactions. So what comes next?

Clearly, they don’t intend to spend scarce funds “catching up” on 1.0—most lack sufficient economic scale or banking systems, and see little value in deploying POS terminals or ATMs, which most can understand.

Meanwhile, though centralized mobile payment systems (i.e., FinTech 2.0) are mature, they come with problems that make these nations hesitant.

First, centralized internet payment systems inherently lead to data monopolies. The operator can freely access, use, and control all users’ private data, easily obtaining core economic intelligence. Under such circumstances, Indo-Pacific nations clearly don’t want foreign-operated centralized systems dominating their domestic markets. Hence, they generally seek to nurture homegrown centralized payment platforms.

Second, fragmented, siloed payment systems create huge integration friction, reducing regional cooperation efficiency. Economic collaboration is vibrant across Africa and Southeast Asia. In Rwanda, Africans I met—from Rwanda, Nigeria, Kenya, or Ghana—all spoke passionately about Africa. Thus, demands for payment and financial system interoperability are extremely high. Throughout the forum, sessions on financial system interoperability consistently drew the largest crowds, fullest rooms, most active speakers, and liveliest discussions—clear evidence of their priority. Yet across dozens of countries, aside from a few with populations over 100 million, most are low-income economies of tens of millions. Each building a few mini-Alipay systems results in over a hundred payment companies total—redundant, wasteful, each too small to achieve scale, hindering deep digital financial development.

Moreover, hundreds of fragmented mini-Alipays generate massive reconciliation friction, undermining collaboration efficiency and trust. Additionally, the regulatory challenges posed by such powerful centralized systems—regarding financial oversight and data privacy—are unresolved even in developed nations, let alone manageable independently by Indo-Pacific countries.

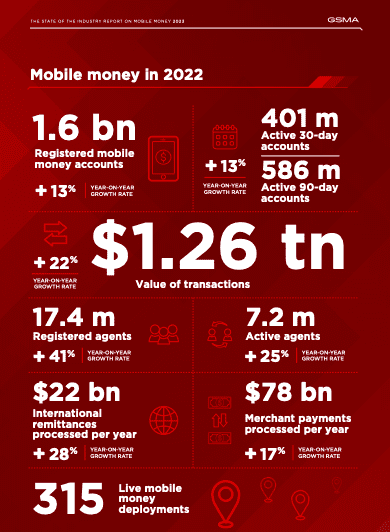

In 2022, Africa’s mobile payment market—586 million active users—was fragmented across nearly 200 providers

Of course, internet payments remain convenient, fast, and relatively mature, so these nations maintain positive attitudes toward them. But as blockchain reveals its technological advantages and application potential, Indo-Pacific countries show exceptional enthusiasm for blockchain-based digital finance systems—greater than elsewhere. Based on conversations, I summarize four key blockchain advantages they value:

First, blockchain balances regional needs for both collaboration and protection of privacy/data sovereignty. In centralized systems, privacy and data sovereignty inevitably concentrate with platform operators because infrastructure operation rights and data ownership are indiscriminately handed over to them. Users must sacrifice data sovereignty for convenience and network effects. For platforms, all regulations amount to slogans without effective technical enforcement. In contrast, blockchain separates operations from data ownership: operational rights distribute across nodes, while users retain data sovereignty via cryptographic mechanisms—eliminating risks of platform usurpation. Meanwhile, blockchain data is tamper-proof and verifiable by third parties, enhancing trust. Trust enables collaboration, so blockchain achieves an ideal balance—perfectly suiting Indo-Pacific regional economic cooperation needs.

Second, blockchain’s open, trustworthy environment and self-executing smart contracts help solve interoperability among different countries’ digital finance systems. Each nation can issue its own digital currencies, certificates, and assets on blockchain. Thanks to blockchain’s intrinsic trust mechanism and standardized data formats, integrating these systems is far simpler and less complex than linking traditional centralized systems, achieving high automation. During the forum, we proposed using Curve-like mechanisms for automated multi-currency exchange. We even envisioned interesting uses of flash loans in certain scenarios.

Third, blockchain makes monetary programming an everyday tool. Blockchain’s cryptographic security model is simpler and more robust than centralized systems, enabling higher openness. Operations requiring层层 authorization in centralized systems can be safely exposed to regular users on blockchain. Monetary programming exemplifies this. Despite years of development, China’s internet payments offer users only basic functions like “red packet grabbing” or “group collections”—features cautiously rolled out by platforms. Ordinary users cannot programmatically control payments. Blockchain allows anyone to program money and payments via smart contracts—an openness unmatched by internet payments and highly attractive to Indo-Pacific nations. When audiences saw demonstrations of ERC-3525’s automatic share calculation, split accounting, UI refresh upon payment status change, setting payment limits and timing, they became excited—eager to customize and control asset and monetary flows themselves.

Fourth, blockchain supports new regulatory frameworks. In centralized FinTech systems, regulators cannot directly supervise at the system level. All rules become gentleman’s agreements, enforced only through spot checks—costly, slow, and ineffective. Many criticize today’s financial regulation in developed countries: stifling honest innovators while helpless against reckless giants—truly painful for allies, pleasing for enemies. On blockchain, once trusted digital identities, accounts, and certificate systems are established, regulators can implement substantive control via smart contract code. Whether preventive legislation, real-time adjustments, or post-event enforcement, efficiency improves by at least two orders of magnitude versus current methods. Thus, digital accounts and certificates became hot topics at the forum. Discussing Nigeria’s CBDC with a Nigerian FinTech expert, he said the main significance isn’t payment—those fixated on payment efficiency miss the point. The key is that CBDC adoption will compel every individual and enterprise to establish digital identities and accounts, use digital wallets. This forms the foundational public infrastructure for next-generation digital economy and financial regulation. I wholeheartedly agree.

Thus, their interest in blockchain follows clear logic. In contrast, large integrated economies like China and the U.S., burdened by user habits and legacy systems, may struggle initially with full blockchain adoption—weighed down, lacking motivation. But late-developing Indo-Pacific nations, unencumbered, urgently seek leapfrog development—bypassing 1.0 and 2.0, directly building future-oriented, cross-border digital economic infrastructure on blockchain.

4. Condition Analysis

Interest exists—but can they succeed? Let’s analyze market conditions.

First, strong demand for cross-border integration. Large single markets may hesitate between centralized and blockchain systems, but regions with intense cross-border needs have clearer demand for decentralized infrastructure like blockchain. The Indo-Pacific region clearly fits—especially ASEAN, Arab Middle Eastern nations, and Africa—all politically fragmented yet economically integrated, forming natural breeding grounds for blockchain.

Second, strong data sovereignty awareness. If a country willingly hands its data sovereignty to a foreign centralized platform, blockchain becomes unnecessary. But as global awareness of data sovereignty and privacy grows, such countries are increasingly rare. Even low-income African nations no longer accept foreign control over their digital economies. This strengthens blockchain’s appeal in the region.

Third, adequate infrastructure—especially internet and mobile internet. Here too, Indo-Pacific nations largely meet requirements. Friends familiar with Africa say that with Chinese support, telecom and internet infrastructure across Africa has advanced rapidly in recent years. Now over 80% of adults own phones, nearly 600 million have mobile payment accounts—meeting basic prerequisites for blockchain adoption.

Fourth, urgent demand for digital financial infrastructure driven by economic development. This too matches Indo-Pacific realities. As global supply chains restructure, the Indo-Pacific region is becoming an economically dynamic zone spanning raw materials to manufacturing. Meanwhile, its 3+ billion population—mostly in low- and middle-income countries—is accelerating growth, potentially entering a period of trade- and regional-cooperation-driven high-speed expansion. This undoubtedly demands digital finance advancement, favoring blockchain development.

Viewed through these four lenses, the Indo-Pacific region appears highly conducive to blockchain industry growth. Therefore, this area could emerge within years as a major blockchain market, possibly leading innovation in certain aspects.

Of course, disadvantages exist—mainly weak infrastructure, with many poor people unable to afford smartphones or internet access. Another major weakness is severe talent shortage, lacking internal capacity to develop such systems, necessitating external input.

5. Singapore’s Strategy

Where there’s demand, supply follows. One institution foresaw this early—Singapore’s MAS. Recently, MAS released a series of projects and white papers clearly targeting cross-border blockchain infrastructure. Three main initiatives stand out:

First, Project Guardian—a cross-border digital asset network composed of multiple blockchains and traditional centralized networks, serving as foundational infrastructure.

Second, Project Orchid—Purpose Bound Money (PBM), programmable digital currency. I’ve introduced this technology twice recently and believe it’s critically important. MAS promotes PBM primarily to provide a new technical framework for regulating monetary payments while preserving key currency attributes.

Third, digital certificate projects like Project Savanah, aiming to reliably represent and verify user identities, accounts, qualifications, and transaction records.

The latter two projects address regulation. The reason enterprise blockchain hasn’t taken off isn’t—as many claim—due to excessive restrictions, lack of speculation, or absence of hype. The root causes are two-fold: accounts aren’t on-chain, and funds aren’t on-chain. Once resolved, businesses and individuals will flock to adopt it. To reassure governments guiding entities onto blockchain, and traditional institutions moving assets, funds, and operations on-chain, the critical prerequisite is ensuring regulatory feasibility. In mainstream economies, anti-money laundering, counter-terrorism financing, and enforcing economic sanctions are non-negotiable requirements—this is crypto infrastructure’s key distinction from enterprise blockchain. If MAS advances these two initiatives—establishing account oversight and fund control—it would effectively close enterprise blockchain’s biggest gaps, making account-on-chain and fund-on-chain achievable.

Clearly, MAS’s entire plan isn’t designed for Singapore alone. With only 6 million people, this strategy’s scale targets populations in the billions. I believe Singapore has learned from nearly a decade of failed enterprise blockchain attempts, now leading a structured, step-by-step strategic development of blockchain and digital economic infrastructure for the Indo-Pacific region.

I couldn’t help thinking: if China had adopted a similar strategy in 2019, leveraging policy momentum to systematically build infrastructure, account systems, programmable money, and regulatory tech frameworks under government leadership, China’s enterprise blockchain applications might already be sizable and export-ready. For infrastructure-level technologies like the internet or enterprise blockchain, government strategy and support play constructive roles in early-stage development. Reviewing early internet history confirms this: market mechanisms excel at discovering innovation directions, but once direction is clear, proper government strategy and industrial policy accelerate growth.

Of course, I’m not saying MAS will definitely succeed—conditions take time to mature. Even with infrastructure built, establishing market liquidity requires significant time. But I believe MAS has identified the right path and target market, potentially creating a rapid feedback loop connecting technological innovation, infrastructure development, and application markets—leading the industry through fast iteration toward global leadership.

Conversations with many Singaporeans reveal their vision: to become the center of tomorrow’s digital economy world. With limited land, Singapore’s physical economy has little room left. But in the digital economy, physical space ceases to constrain—Singapore can aspire to become a global digital economic powerhouse. That is its ambition.

With clear demand present and Singapore leading, I now believe the Indo-Pacific region will become a hotspot for blockchain industry development. This market offers rare opportunities for industry practitioners committed to creating real economic value through blockchain.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News