Four-Quadrant Token Economic Model (I): Dual FT Model

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Four-Quadrant Token Economic Model (I): Dual FT Model

Innovations and applications of the dual-token model continue to emerge, and compared to single-token systems, the design space for dual-token models has been significantly expanded.

Authored by: @Jane @Gannicus, Buidler DAO

Orchestrated by: @Heiyu Xiaodou

Introduction

Since Axie Infinity adopted a dual-token model in 2020, the dual-token structure has almost become standard in the GameFi space. Its influence extends beyond gaming—projects in DeFi and Proof of Physical Work (PoPW), among other broader fields, have also adopted dual-token models. But is adopting a dual-token system always necessary compared to a single-token model? What are the advantages and disadvantages of dual tokens? How do the two tokens relate to each other? What lessons can we learn from past dual-token projects? And what considerations should be made when designing such systems? This article aims to explore these questions.

Projects referenced include StepN, Axie Infinity, Crabada, Helium, Hive Mapper, and others.

Overview of Dual-Token Models

A dual-token model involves distinguishing tokens based on their primary use cases. In Hashkey’s whitepaper “Web3 New Economy and Tokenization,” they define a “three-token model”: utility tokens, equity tokens, and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), representing access rights, ownership shares, and digital certificates respectively.

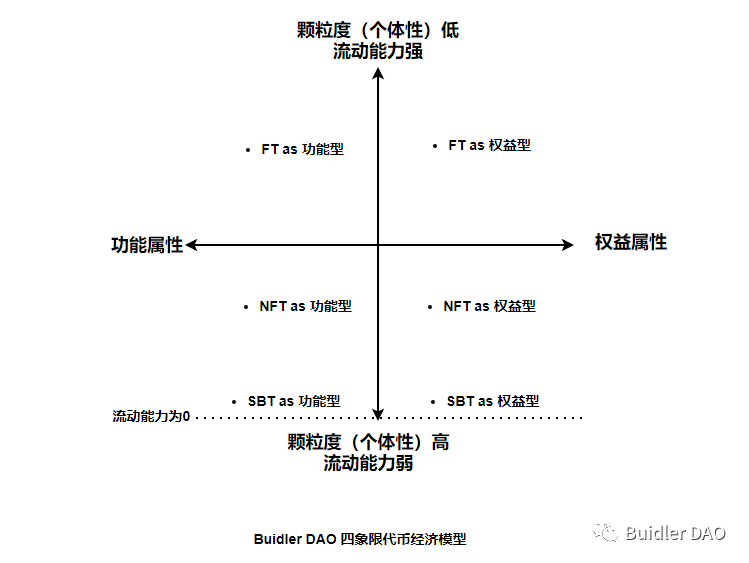

However, during discussions within the Buidler DAO Economic Modeling Group, we observed that the distinction between utility and equity tokens lies primarily along the dimension of usage versus ownership rights. Meanwhile, NFTs (or SBTs) cannot be simply grouped as a third category alongside them because the contrast to NFTs is not another token type but rather fungible tokens (FTs) with no granularity. The key differentiating variable here is granularity and associated liquidity, which represents an entirely separate dimension.

Based on two dimensions of tokens, we’ve developed a four-quadrant framework—tentatively named the Four-Quadrant Token Economic Model. This model resolves certain contradictions in the “three-token” approach, such as how some tokens can simultaneously be both NFTs and utility tokens, or both NFTs and equity tokens. In the diagram below, we treat SBTs as a special case where NFT liquidity equals zero.

As the first piece in this series, we will focus on Quadrants I and II—the dual-token model using FTs for utility and governance purposes. Future articles will explore more imaginative scenarios involving NFTs (SBTs) serving as utility or equity tokens.

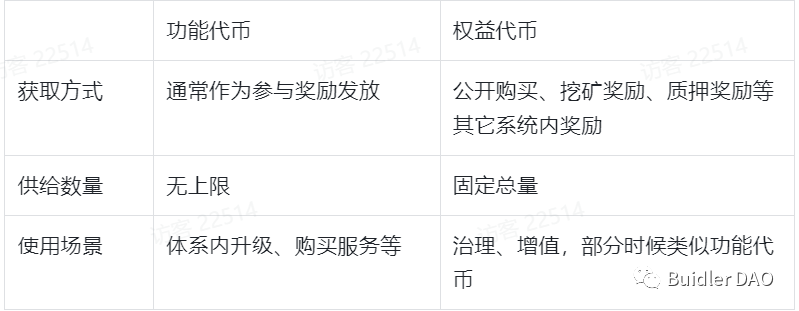

In this context, utility tokens are primarily used to enable specific mechanisms within the system—such as asset upgrades or service payments—and function similarly to in-game currencies. They may also serve as rewards distributed according to predefined rules to users who participate in platform activities. Utility tokens are typically minted on demand and often have no supply cap.

Equity tokens, as the name suggests, embody both “rights” and “benefits.” The “right” refers to governance power—holders can vote and participate in decision-making processes. For example, Uniswap and Lido issue tokens purely for voting rights. The “benefit” reflects scarcity and potential appreciation in value, sometimes even including revenue-sharing akin to stock dividends. Many VE-based systems allow staking tokens to receive veTokens that grant voting and profit-sharing rights. In early markets, many projects defined equity tokens as dividend-bearing “shares.” However, due to regulatory concerns—especially avoiding classification as securities by the U.S. SEC—most modern projects now avoid designing pure dividend-distributing equity tokens. Initially, equity tokens were crucial fundraising instruments, sold publicly to investors. To provide stable expectations, they often follow Bitcoin-like designs with fixed total supplies.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Dual Tokens

Separating equity and utility tokens helps prevent infinite dilution of governance rights caused by continuous inflation driven by utility demands, thereby contributing to a relatively stable governance structure. Additionally, since equity tokens tend to attract stronger speculative demand, keeping utility token prices relatively controlled becomes easier. In gaming contexts, for instance, a dual-token model can mitigate high entry barriers caused by speculation-driven spikes in utility token prices, allowing ordinary players freer participation. The in-game economy can remain healthier and more balanced. For system designers, this provides more effective tools to maintain stability.

Yet flexibility comes with complexity. Managing a dual-token system is far more than twice as difficult, especially considering possible interdependencies between the tokens. (For example, a Binance report analyzing Axie’s two tokens found a correlation coefficient of 0.47—indicating a positive relationship.) Once multiple tokens exist within a system, fairly allocating value becomes essential. Moreover, because utility tokens are usually infinitely mintable, they are prone to inflationary pressure. If excessive inflation or related issues cause price declines, more tokens must be issued to maintain sufficient user incentives, further exacerbating inflation. Thus, dynamically balancing supply and demand poses a major challenge—one clearly evident in past GameFi implementations. For average users, managing multiple tokens may also increase cognitive load.

Qualitative View on Dual-Token Pricing

Utility token prices can either be fixed or variable. When fixed, utility tokens are pegged to fiat currency. For example, in the IoT project Helium, its utility token Data Credits (DC) maintains a constant rate: 1 DC = $0.00001. This means network service costs are predictable. Users don’t need to hoard DC—they buy only when needed and spend immediately, resulting in very high velocity for the token. With variable pricing, excluding pure speculation, if the growth rate of economic activity exceeds the inflation rate of the utility token, the intrinsic value per unit can rise, giving it investment appeal.

Equity tokens resemble stocks—their prices reflect investor expectations about future development, team credibility, and broader market conditions. However, for regular users holding small amounts, influencing governance is impractical. If equity tokens offer only voting rights, they may fail to incentivize long-term holding or active participation. Broader utility increases holding motivation and reduces selling pressure. Some projects enhance equity token utility through additional benefits:

-

Staking enables higher returns

In Axie Infinity, players stake AXS to earn additional AXS rewards, increasing yield.

-

Governance determines reward distribution

When users influence how rewards are allocated—affecting their own interests—they’re more motivated to hold and vote. See Curve’s reward allocation mechanism for reference.

-

Equity tokens have partial utility functions

Beyond utility tokens, some scenarios require combining equity tokens. But this blurs the boundary between the two types and requires careful consideration.

Additionally, incorporating token burn mechanisms can reduce circulating supply and help stabilize token prices.

Exploring Relationships Between Dual Tokens

The existence of dual tokens gives system designers greater control. These two tokens aren't necessarily independent—they can be linked via mechanisms affecting quantity and price, guiding the system toward equilibrium or desired states. These hidden interactions and hierarchical relationships represent the elegance of dual-token design.

Dynamic Interaction Between Dual Tokens

We examine StepN and Helium to illustrate how dual tokens can interact.

StepN: GST vs GMT

StepN features two tokens: GST (utility) and GMT (equity). Throughout its evolving economic model, these tokens continuously influence each other.

a) Optional Rewards

In StepN, once shoes reach level 30, users choose between receiving GST or GMT rewards. Since the total GMT reward pool is fixed, if many users opt for GMT, individual payouts decrease. At a tipping point, users may switch to GST rewards, and vice versa. By introducing reward uncertainty, users are incentivized to adapt their choices. Ideally, this leads to dynamic price balance between the two tokens.

b) GMT Burning Mechanism

Burning mechanisms link demand for GST to GMT's supply and price. Examples include:

1) Daily GST caps vary by shoe level (5–300). When users hit 90% of their daily limit at max level (300), they can burn GMT to raise the cap;

2) Upgrading to specific levels (5/10/20/29/30) requires burning GMT. After upgrade, as above, daily GST earnings increase.

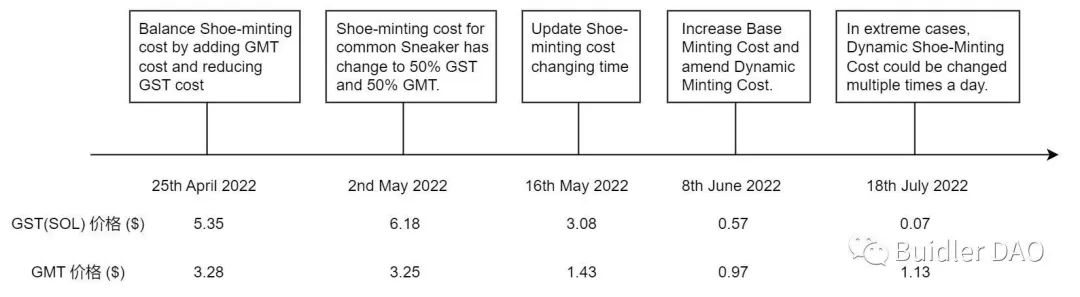

c) Dynamic Shoe Minting Cost

Shoe minting is central to StepN. Another dynamic adjustment appears in minting cost.

Initially, minting required only GST. As GST prices rose, one mitigation strategy was introducing GMT into minting costs. Later, the ratio of required GST to GMT was further adjusted.

However, frequent manual interventions create unstable expectations for users and investors. If minting cost could correlate with GST price, the system could self-regulate. To achieve this, the team introduced a dynamic minting mechanism. The latest formula is:

Minting cost = GST (A) + base GMT (B) + additional GMT ([A+B]*x)

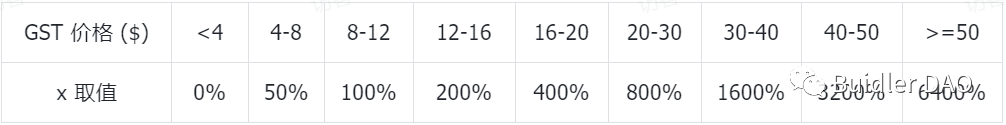

Where x varies with GST price fluctuations:

Under this mechanism, required GST is constant. If GST price rises, more GMT is needed for minting, increasing GMT demand. Consequently, GST’s share of minting cost is capped, and users may sell GST to buy GMT, adding downward pressure on GST price, helping it cool down. Clearly, the team doesn’t want GST prices too high, preferring them within a reasonable range. Shifting buying pressure to GMT during high GST prices signals that GMT is the primary value-holding token.

Different tokens represent different stakeholders and reflect strategic priorities. Only high-tier shoe owners receive GMT rewards, so others must buy GMT on the open market to upgrade or mint. Some community members view this as unfair to lower-tier players. Regarding big vs. small players, founder Yawn Rong stated in an AMA: “In economic models, large players support GST price and floor shoe prices. In x2e projects, you must understand your revenue sources—or risk collapse.” From a business perspective, focusing on income and risk management is valid. Yet building a vibrant community also requires balancing broad player interests—extreme bias or absolute fairness are both unwise. Through the dual-token minting formula, we glimpse the team’s original intent and can track ideological shifts through future iterations.

In summary, the team influences demand and supply for GST and GMT through minting costs, enabling price regulation. The dynamic interaction between GST and GMT is fully demonstrated here.

d) Expanding GMT Use Cases

Currently in StepN, GMT is mainly used for upgrades and minting. Developing more GMT utilities is a core team goal. This enhances GMT appeal and may indirectly boost GST demand. In a January AMA, the founder noted early signs of this trend amid market recovery. Whether this linkage stems from internal mechanics or sentiment remains to be studied.

Helium: BME Model

Helium introduces token linkage primarily through burning, using the Burn-and-Mint Equilibrium (BME) model.

a) Introduction to the BME Model

Helium has two tokens: HNT (equity) and DC (utility). HNT has a fixed supply (223 million), halves every two years, and is distributed as rewards to miners following set rules. DC is the utility token. Network usage is billed in DC: 1 DC = $0.00001 per 24 bytes transmitted. Users purchase and burn HNT to obtain DC. Due to HNT price volatility, the amount burned depends on oracle quotes.

In the BME model, burning is just the first step. In the next time interval, the system mints new HNT tokens equal to a function of the amount burned—specific to each project. In Helium, this function has evolved. Currently: if burned amount is below threshold B, minted amount equals burned amount (equilibrium); if burned exceeds B, minted amount remains B (capped).

b) Dual-Token Linkage in BME

DC represents demand. Through this asynchronous burn-and-mint mechanism, HNT supply and price automatically correlate with demand. For example, strong market demand causes burn volume to exceed mint cap, putting HNT into deflation. Reduced supply tends to increase price. Crucially, higher HNT prices mean fewer tokens are needed to buy the same service, helping restore equilibrium.

Thus, under BME, HNT effectively captures platform economic value. Compared to simple payment-only tokens, user holding incentives are significantly stronger. Separating utility and equity tokens also ensures network usage fees remain stable regardless of HNT price swings—an important benefit of BME.

However, Helium currently faces weak demand—burn volumes fall far short of the mint cap. This creates temporal misalignment between the two tokens. Viewing Helium as a two-sided platform, HNT rewards prioritized supply-side (miners) development, while DC-backed demand remains underdeveloped.

Token-based incentives are common in blockchain. Extending from Helium’s case: how can demand be better incentivized? Can supply and demand grow symbiotically? This might inspire alternative dual-token designs and reward structures. If supply and demand mutually reinforce each other, the two tokens could achieve closer temporal synchronization.

Hierarchical Relationships Between Dual Tokens

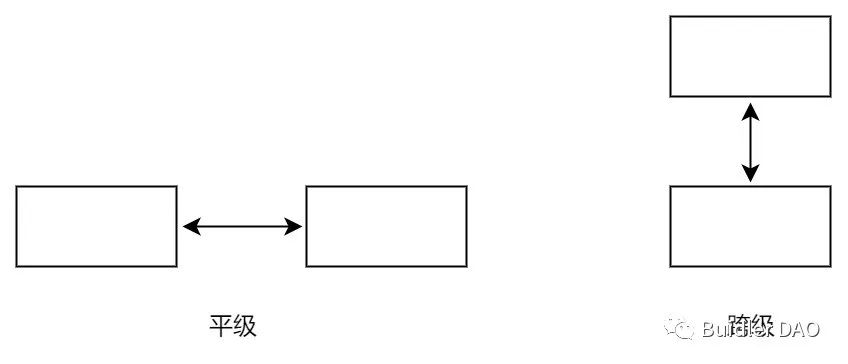

When multiple tokens exist, beyond interaction, they may form hierarchical relationships—either peer-level or cross-tier. Different hierarchies lead to distinct interaction patterns.

In Helium, HNT and DC represent supply and demand—same-tier tokens. This peer-level design aligns with its initial strategy of independently growing supply and demand.

In StepN, GMT is clearly a higher-tier token than GST. As the main value anchor, GMT spans realms (within StepN), projects (across FSL ecosystem), and platforms. In the team’s new NFT marketplace MOOAR, GMT serves again as the equity token. GMT also has concrete utility: pricing NFT trades, Launchpad voting, and burning GMT to generate AIGC NFTs.

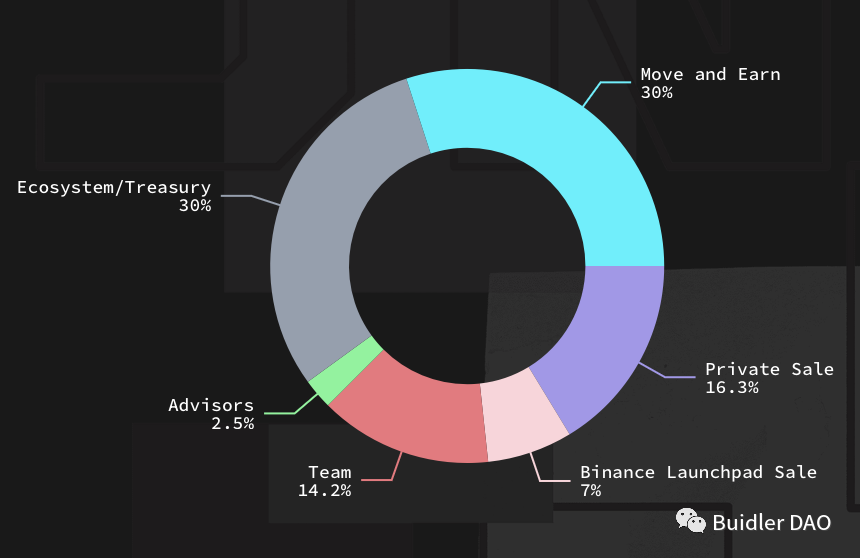

MOOAR’s GMT rewards come from the 30% ecological allocation in StepN’s token distribution (see below). More ecosystem-benefiting projects are expected. Designers hope various initiatives will collectively boost GMT prosperity. GMT holders from external projects may flow into StepN, indirectly increasing GST demand.

https://stepn.com/

Summary

Compared to isolated, one-way designs, effective interactive mechanisms add vitality and endogenous stability to token systems, potentially spawning nonlinearly emergent ecosystems. Combined with hierarchical thinking, designers gain expansive creative freedom. Key challenges involve establishing sound value attribution mechanisms and providing meaningful incentives to all token holders. Much remains to be explored.

Evolution of Dual-Token Systems

Dual-Token → Multi-Token

From dual-token models, we naturally extend to multi-token scenarios. One intuitive assumption: more tokens, more complex mechanisms, larger operational headroom, thus greater prosperity. But the answer is no. Consider Crabada, a P2E game attempting a three-token model.

Besides utility token (TUS) and equity token (CRA), Crabada introduced CRAM in December 2021 as a staking reward. CRAM has no supply cap. Staking 50 CRA yields 1 CRAM weekly. Users can sell CRAM directly, use it as lottery tickets, expand teams, etc. CRAM and TUS are exchangeable on Trader Joe.

Earlier, we noted Axie rewards stakers with AXS itself. Crabada’s choice to introduce a third token hints at broader ambitions: enrich gameplay and interactions over time while building a more robust in-game economy. Another advantage: rewarding with native tokens turns staking into delayed payout, increasing late-stage inflation. Rewarding with a third token—assuming sufficient sinks—reduces selling pressure while enhancing fun—a win-win.

But this experiment failed. In May 2022, the team announced gradual replacement of CRAM with TUS, phasing out CRAM entirely. Beyond cited macro factors, unclear what metrics drove this reversal—perhaps CRA’s sustained price drop since late March eroded staking value.

Clearly, three-token systems pose greater challenges than dual-token ones. Simply adding tokens isn’t necessarily beneficial when transitioning from Play-to-Earn to Play-and-Earn. Was staking the right place for a third token? Would CRAM have succeeded if launched during a bull market? These remain open questions.

Still, Crabada’s retreat doesn’t mean multi-token systems are invalid. Valid reasons for introducing multiple tokens include:

1) Introduce tokens based on clear positioning and objectives;

2) Consider management difficulty and inter-token dynamics, aiming for systemic stability.

Dual-Token → Single-Token

With dual tokens nearly default, can single-token models still work? Nat Eliason proposed an elegant solution showing significant design freedom even within single-token frameworks.

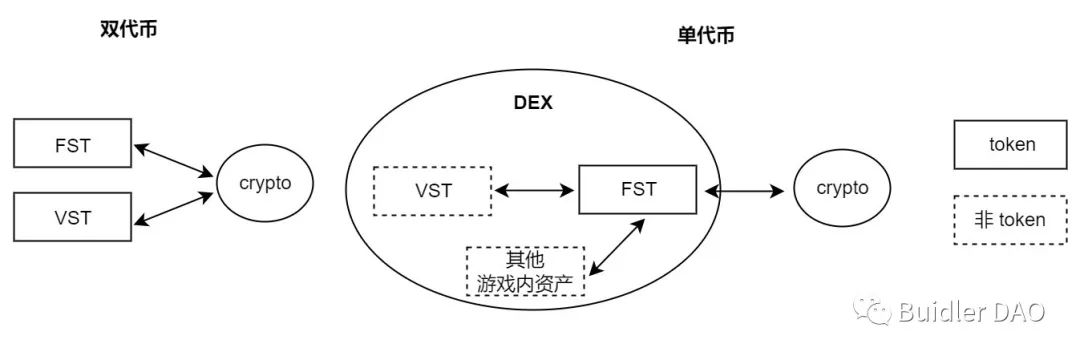

Take a Fixed Supply Token (FST)—it acts as an investment asset and bridge between in-game currency and crypto. A Variable Supply Token (VST) still exists but circulates only internally, not directly linked to external crypto. Designers build a DEX enabling swaps between FST, VST, and other in-game assets, as shown below:

Beyond currency DEX, there’s also a goods marketplace. Items can be priced in FST or ETH/crypto. The platform earns fees. Value accrual for FST is clear—burn collected FST fees or distribute received crypto as staking rewards to FST holders.

In this system, as in-game items grow while FST supply stays fixed, FST purchasing power theoretically increases—encouraging continued holding and staking. Of course, FST connects to crypto markets and is affected by macro trends. But compared to Crabada’s failed staking scheme, FST enjoys stronger in-game value backing, possibly reducing macro sensitivity. Active trading—even with falling FST prices—could yield better returns via fee income.

Nat’s design rethinks how project tokens interface with crypto—not every in-game currency needs direct real-world liquidity. Some closure and a unified token system may aid price stability and clearer value anchoring. StepN’s founder expressed similar hopes for keeping GST internal. Beyond design flexibility, this model retains speculative and investment aspects of crypto, achieving a kind of balance reminiscent of traditional non-token games.

Reputation-Based Dual-Token Systems

So far, we haven’t discussed reputation tokens—those tied to user contribution verification. The challenge: if reputation tokens are tradable, their signaling function weakens. How to preserve identity value while offering economic benefits?

In the paper “A Novel Framework for Reputation-Based Systems,” Koodos Labs founder Jad Esber and Harvard professor Scott Kominers offer brilliant insights into reconciling reputation signals with rewards, proposing a dual-token reputation system. Their model includes “points” (non-transferable reputation signals) and “coins” (transferable assets periodically distributed to point holders). Coins act as dividends proportional to points held. This creates a virtuous cycle: demand for coins motivates users to earn more points, driving greater contributions.

Key design elements include effectively linking point holders to contribution sources—providing incentives at the right moments. Point issuance rules must be transparent so participants can adjust behavior accordingly. Designers can fine-tune parameters like dividend size, frequency, relation to points, expiration, etc. Still, over-incentivizing is risky. True product-market fit combined with smart incentives is the path forward. In practice, reputation incentives are often implemented via NFTs.

Jad and Scott’s model balances reputational integrity with liquidity. Chain game Fusionist’s newly launched mainnet Endurance adopts a similar dual-token reputation system. Looking ahead: how to identify stages needing strongest incentives? How should reputation evolve with contributor communities? Can all contributor types be included? How should reputation tags map to governance weight? Refining these questions leads to better reputation and incentive designs, highly applicable in concrete settings like DAO governance and operations.

Considerations When Designing Dual Tokens

Reward Design

Reward rules are invisible conductors—the subtle yet tangible force shaping user behavior. Some directly tie to actions. Hence, clarity of purpose is critical before setting incentives. Blindly flooding users with rewards hoping scale alone wins won’t sustain growth—it’ll quickly fade. Clarity of purpose is just the start. Extracting optimal metrics, ensuring rewards hit the right triggers, and fairly distributing among multiple participant types—all are vital for effective implementation. Living systems constantly evolve. At different stages, target behaviors, focal actors, and reward allocations may need iteration. This requires close tracking of data, community feedback, and alignment with shifting strategy and priorities.

Take decentralized mapping platform Hive Mapper: they identify three key metrics for map quality—coverage, freshness, and accuracy. Early on, 90% of rewards go to contributors expanding coverage. As the map matures, rewards shift toward quality assurance and annotation. This exemplifies goal-driven reward design adapting to system evolution. Subtly, designers differ on priority. If starting with coverage struggles against incumbents, one must ask: which entry point offers sustainable differentiation? Reward placement acts like a leverage point, reflecting strategic insight into competition and winning conditions.

In sum, good incentive design achieves precise alignment—precise measurement and correct positioning. Misaligned rewards distort the system. Goals reflect team values and vision. Also, token rewards aren’t free—they require cost-benefit analysis and long-term ROI assessment.

Controlling Utility Token Inflation

Given utility tokens are usually infinitely mintable, many past cases succumbed to hyperinflation. Managing a dynamic open economy is extremely hard. Conceptually, designers have several levers:

-

Control issuance—carefully manage token distribution, limiting total volume and frequency;

-

Expand sinks—create diverse and rational consumption channels; note: if spending today boosts tomorrow’s earning ability, this merely delays inflation, not solving it long-term;

-

Implement buybacks and burns to reduce circulation;

-

Build treasury reserves—stronger buffers enhance anti-inflation capacity; during bull markets, maximize accumulation

Equity Token Release and Value Accrual Mechanisms

To give equity tokens holding value, establish clear value accrual paths—via revenue sharing, staking rewards, buybacks, burns, etc. Also, if assigning utility functions to equity tokens, ensure clear separation from true utility tokens. Overlap risks confusion and diluted value attribution.

Moreover, equity token release schedules offer design flexibility. Typically, release amount and speed are fixed, sometimes halving every few years. But this isn’t mandatory. Hive Mapper explores variable-rate release.

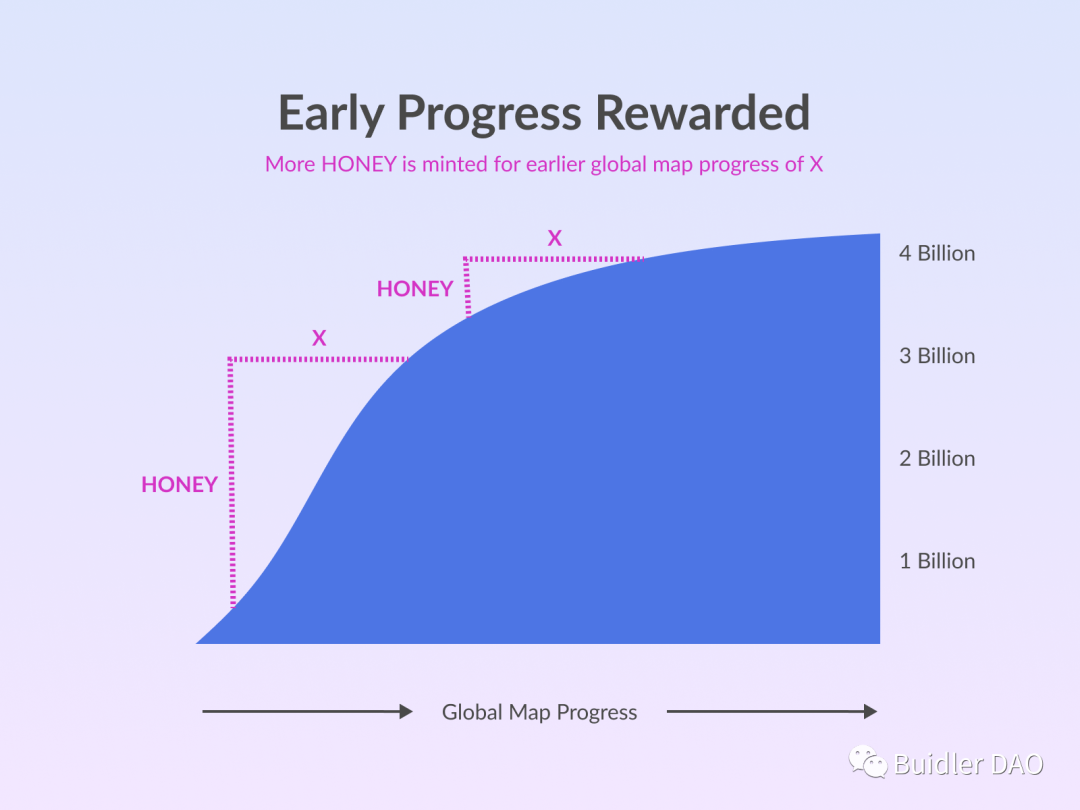

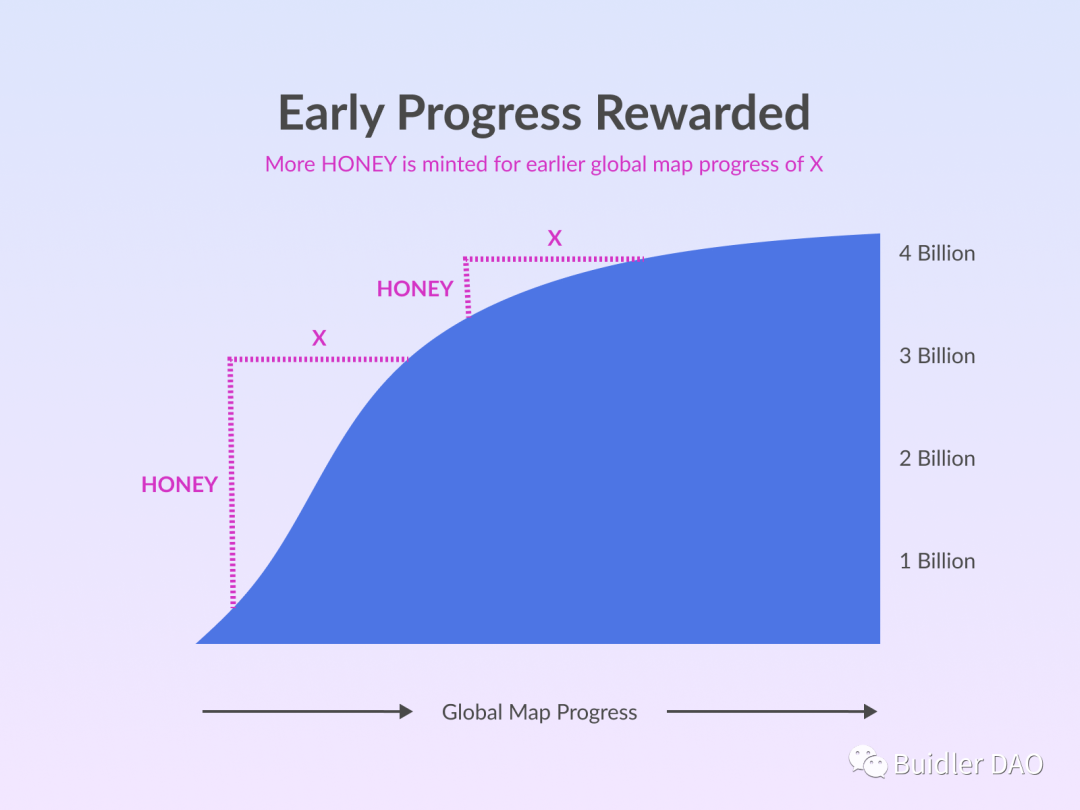

Hive Mapper’s main token HONEY has 1 billion total supply, with 400 million allocated to contributors. As seen in the graph below, the x-axis tracks map progress, not time—meaning releases depend on achievement, not clock. The concave curve implies decreasing release rates over time—designed to reward early contributors more generously.

https://docs.hivemapper.com/honey-token/earning-honey/global-map-progress

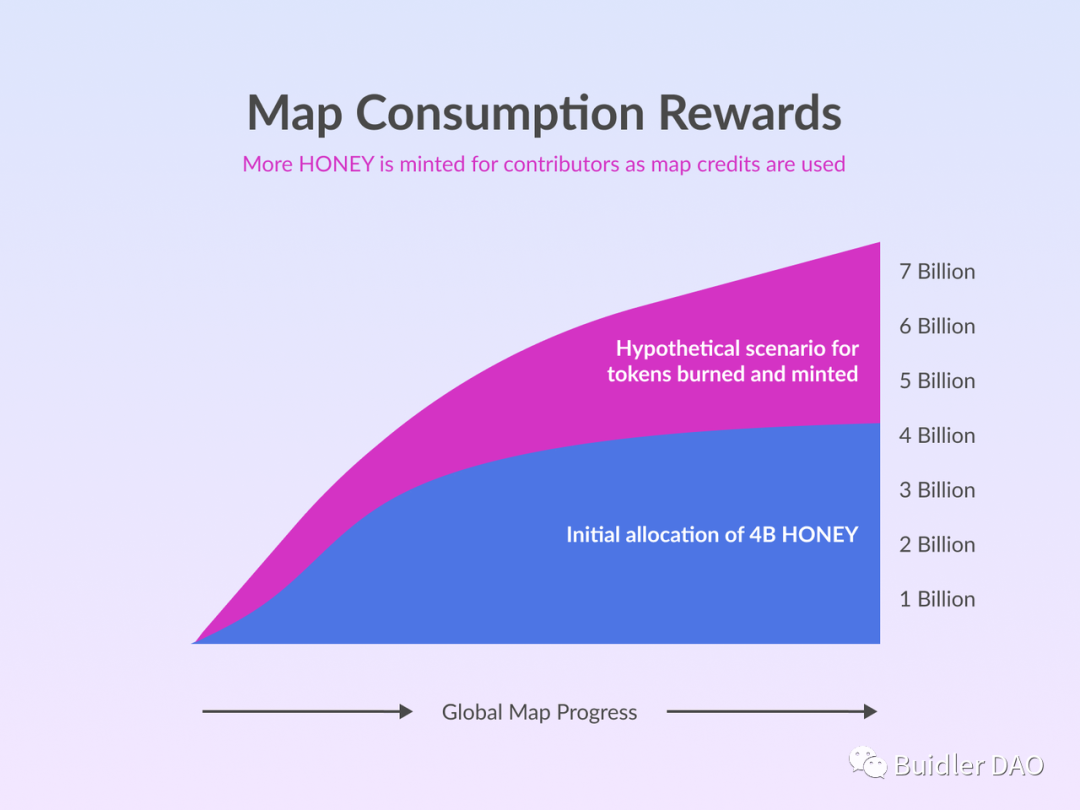

On top of this, another layer (pink area in next image): users burn HONEY to access services. The system then mints an equivalent amount back into the reward pool, combining with newly released tokens as rewards.

https://docs.hivemapper.com/honey-token/earning-honey/map-consumption-rewards

The brilliance lies in linking miner rewards to both supply (map progress, blue) and demand (burned tokens, red). To keep earning, miners must advance mapping or stimulate demand. As progress continues, new releases shrink—making demand size increasingly critical for miner profitability. Well-designed rules (adequate rewards) may spawn novel roles—like miners actively driving demand.

Through Hive Mapper’s unconventional design, we see high degrees of freedom in dual-token systems. Changes should serve better growth and incentives—not be bound by convention. Adjustable release rates, recycling burned tokens—these make total supply dynamic, opening rich design possibilities.

Creating Value Beyond Virtual Worlds

Why can Hive Mapper design such models? One reason: PoPW projects have clear goals—like map progress—that generate real-world value. In contrast, obsessing over intricate parameter tuning in virtual worlds without pursuing deeper purpose leads to narrow solutions and likely Ponzi-like collapses.

This explains why Axie pushes from Play-to-Earn to Play-and-Earn, and StepN seeks to connect gaming with fitness. Unlocking broader value enables higher-dimensional economic design—likely more sustainable. A seasoned StepN user suggested exploring external revenue streams—to reduce reliance on shoe sales and whales—such as partnering with insurers. While current income may be negligible, costs are low, outreach extends beyond crypto, and richer user profiles emerge.

Of course, challenges remain: bridging virtual and physical worlds, abstracting meaningful metrics into digital systems. But with clear purpose, methods can iterate. Harder is choosing to transcend internal cycles and build larger economic systems—requiring longer, harder effort.

Conclusion

Dual-token model innovation continues evolving. Compared to single-token designs, dual-token systems vastly expand design space—especially in inter-token relationships, where subtle interaction mechanisms can guide unique user behaviors. On this foundation, we can extend to multi-token, reputation-based, and other diversified architectures.

If we divide model design into purpose and mechanism, purpose guides direction, while mechanism quality determines sustainability. Axie’s founder Aleksander Larsen once said their economic design with Delphi Digital started from the principle of rewarding active contributors more—ultimately benefiting the entire system. Second, as discussed, consider whether the system can connect to the real world and generate value beyond virtual constructs. Only then should we refine mechanisms and parameters. Ideal design is bidirectional: a healthy economy generates real value, which in turn reinforces economic stability.

Extending further, could dual-token models apply in broader domains—like consumer membership programs or ad systems that genuinely reward users? It is through such explorations that economic design methodologies continue advancing, hopefully enabling new, more efficient business models and companies.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News