From a technical perspective: Why deflationary tokens are vulnerable to attacks

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

From a technical perspective: Why deflationary tokens are vulnerable to attacks

This article will discuss and analyze the reasons why deflationary tokens are attacked, and provide corresponding defense solutions.

Overview

Deflationary tokens on blockchains have recently been frequently targeted by attacks. This article discusses and analyzes the reasons behind these attacks on deflationary tokens and proposes corresponding defensive measures.

There are typically two ways to implement a deflationary mechanism in a token: burning mechanisms and reflection mechanisms. Below, we will analyze both implementations and their potential vulnerabilities.

Burning Mechanism

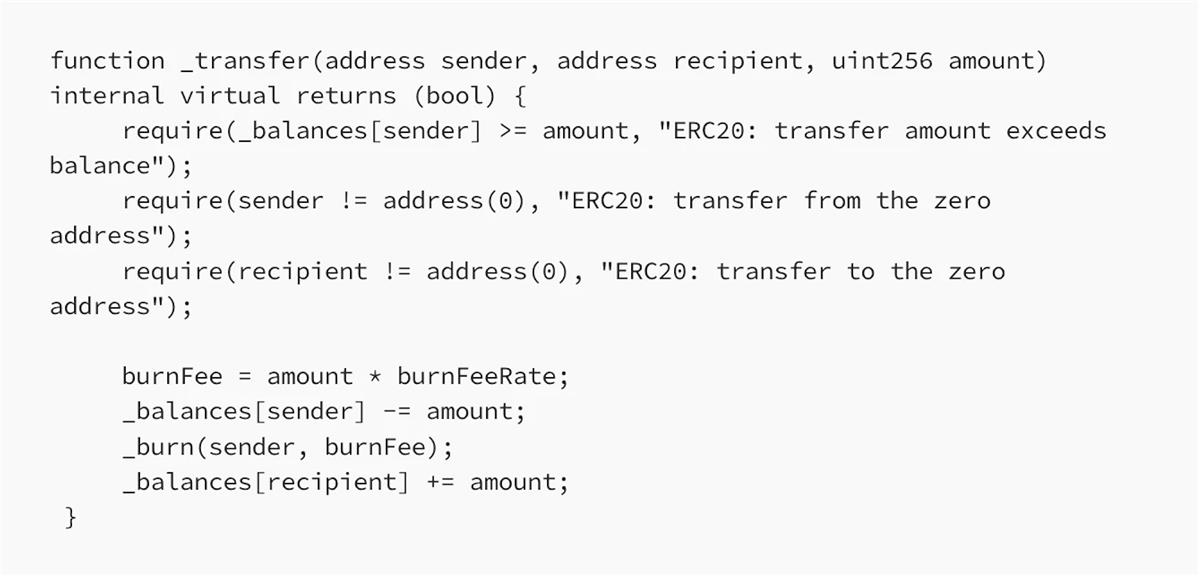

Tokens with a burning mechanism usually implement the burn logic within their _transfer function. Sometimes, the sender bears the transaction fee. In such cases, the recipient receives the same amount of tokens, but the sender must pay additional tokens to cover the fee. Here is a simple example:

Next, we discuss the risks associated with this approach.

At first glance, the token contract may appear secure. However, blockchain environments involve complex interactions that require careful consideration from multiple angles.

Typically, to establish a market price for the token, project teams add liquidity to decentralized exchanges like Uniswap or Pancakeswap.

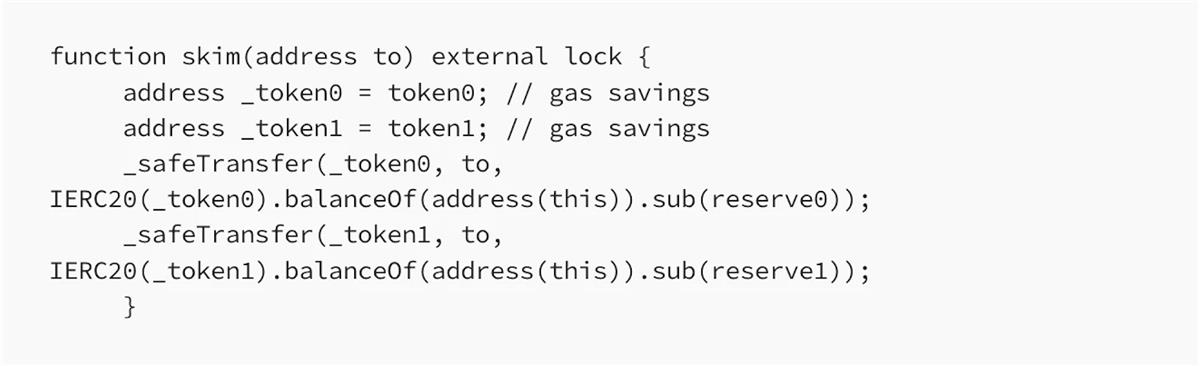

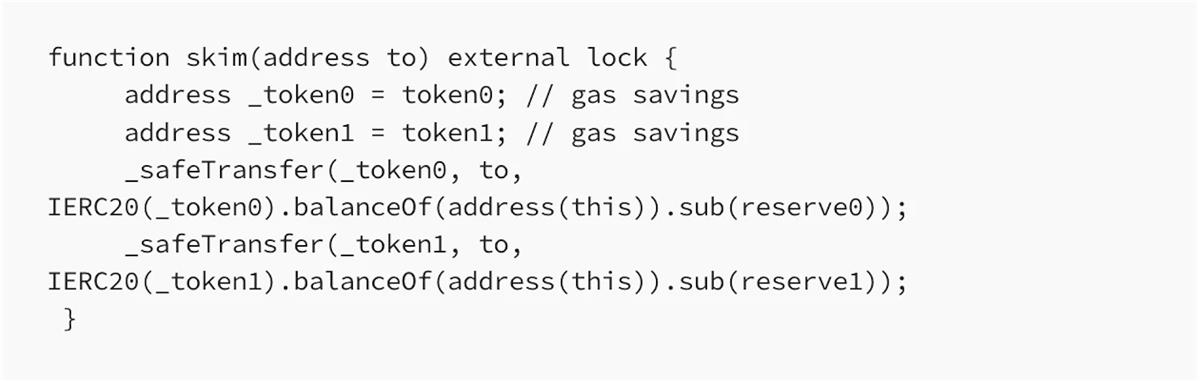

In Uniswap, there exists a function called skim, which transfers the difference between the liquidity pool's token balances and reserves to the caller, thereby balancing them:

Here, the sender becomes the liquidity pool. When _transfer is invoked, part of the tokens in the pool are burned, causing a partial increase in token price.

Attackers exploit this behavior by directly transferring tokens into the liquidity pool, calling the skim function to withdraw funds, and repeating this process multiple times. This burns a large number of tokens in the pool, sharply increasing the price, after which attackers sell their tokens for profit.

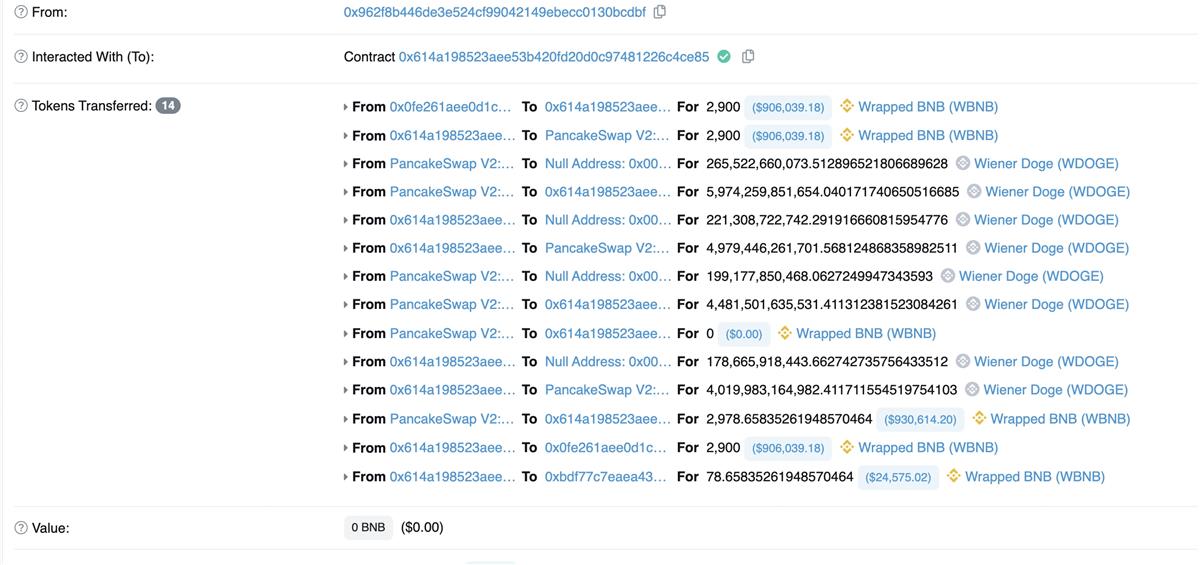

A real-world attack case: Winner Doge (WDOGE):

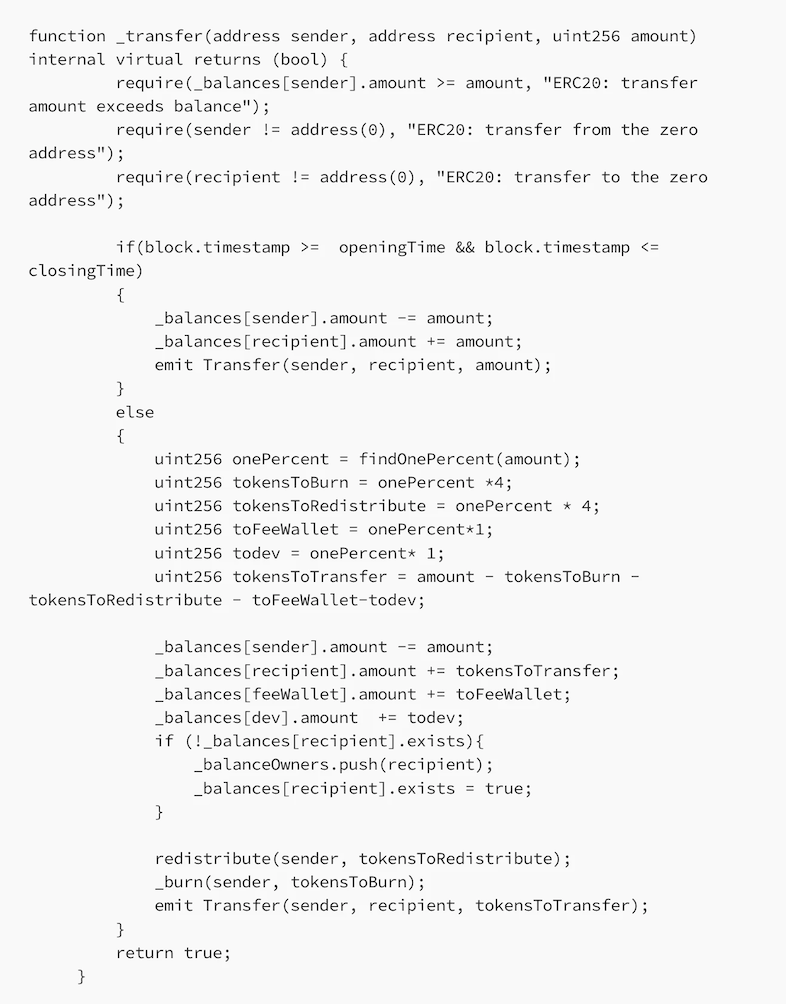

In the WDOGE contract’s _transfer function, when block.timestamp > closingTime, the code enters the else branch. On line 21, the transfer amount is deducted from the sender’s balance; on line 31, an additional tokensToBurn amount is burned from the sender. Attackers exploited this fee mechanism to steal all the value (WBNB) from the liquidity pool using the aforementioned method.

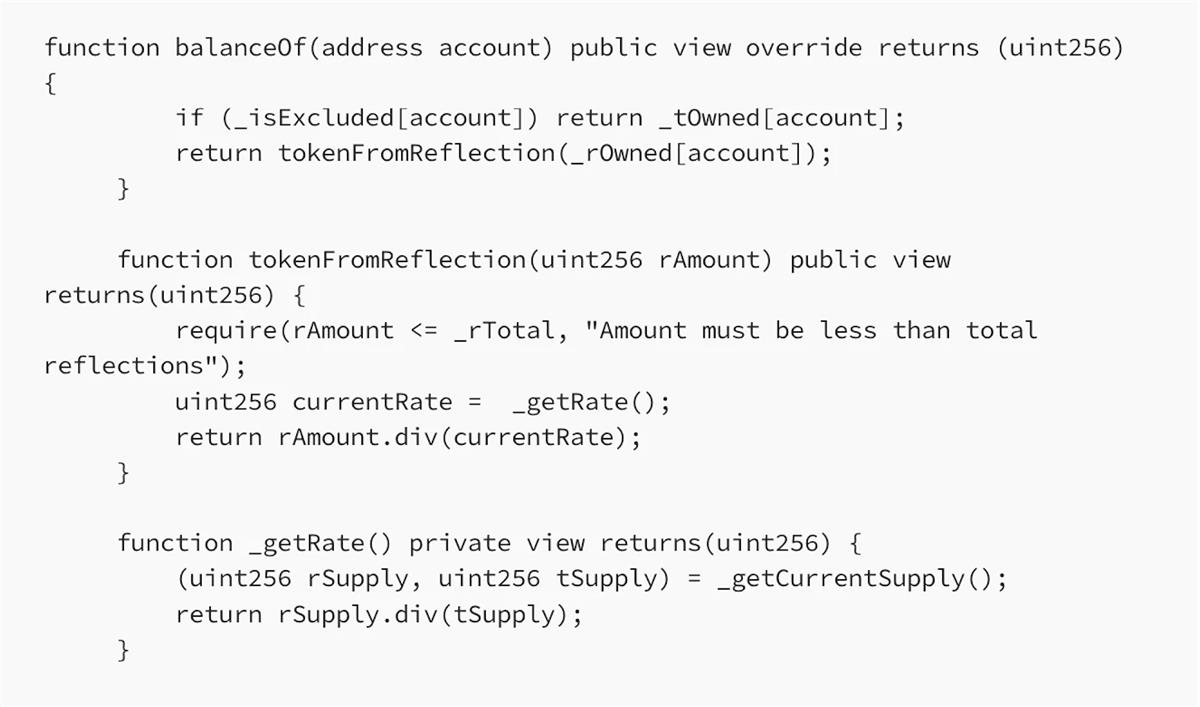

Reflection Mechanism

In reflection mechanisms, each transaction incurs a fee used to reward token holders. However, no actual transfers occur—only a coefficient is adjusted.

In such systems, users have two types of token balances: tAmount (the actual token amount) and rAmount (the reflected amount), with a ratio of tTotal / rTotal. A typical implementation appears as follows:

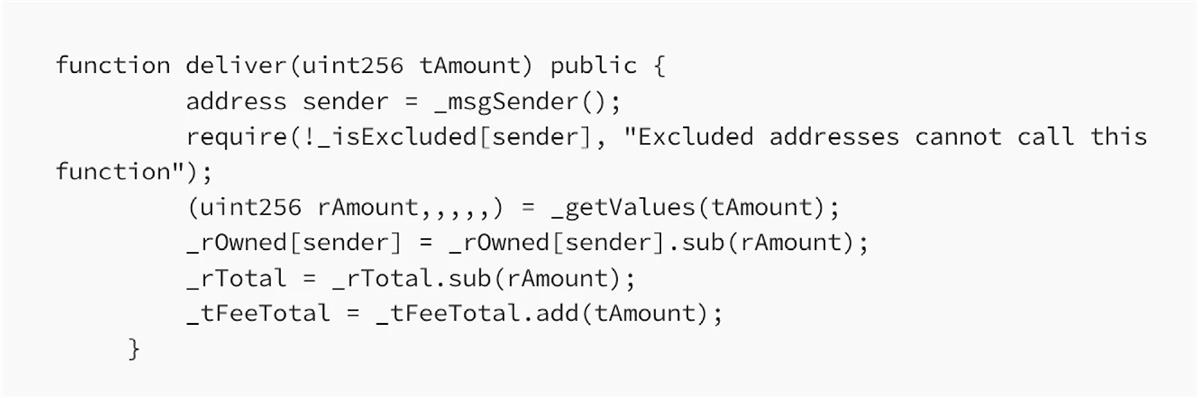

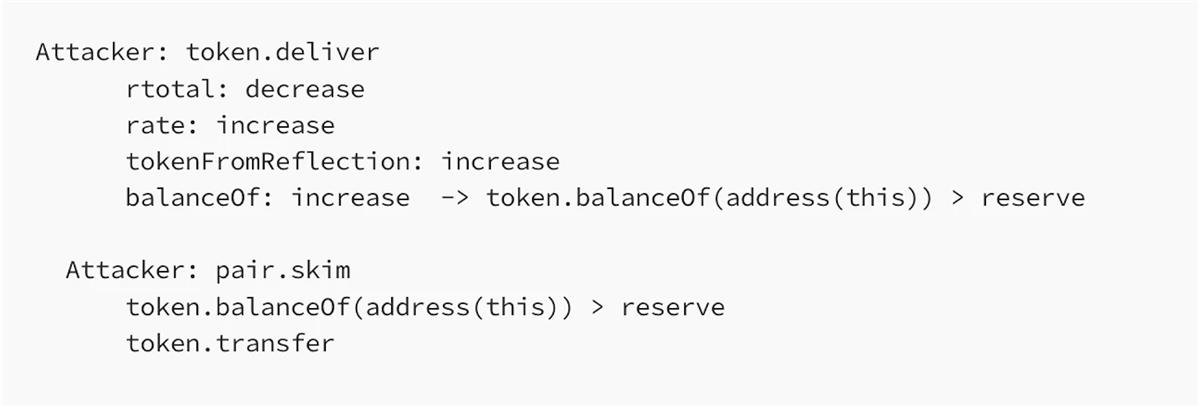

Reflection-based tokens generally include a function named deliver, which burns the caller’s tokens and reduces rTotal, thereby increasing the ratio and consequently increasing other users’ reflected token amounts:

Attackers noticed this function and leveraged it to attack corresponding Uniswap liquidity pools.

How can they exploit this? Again, starting from Uniswap’s skim function:

In Uniswap, reserve refers to the stored reserves, which differ from token.balanceOf(address(this)).

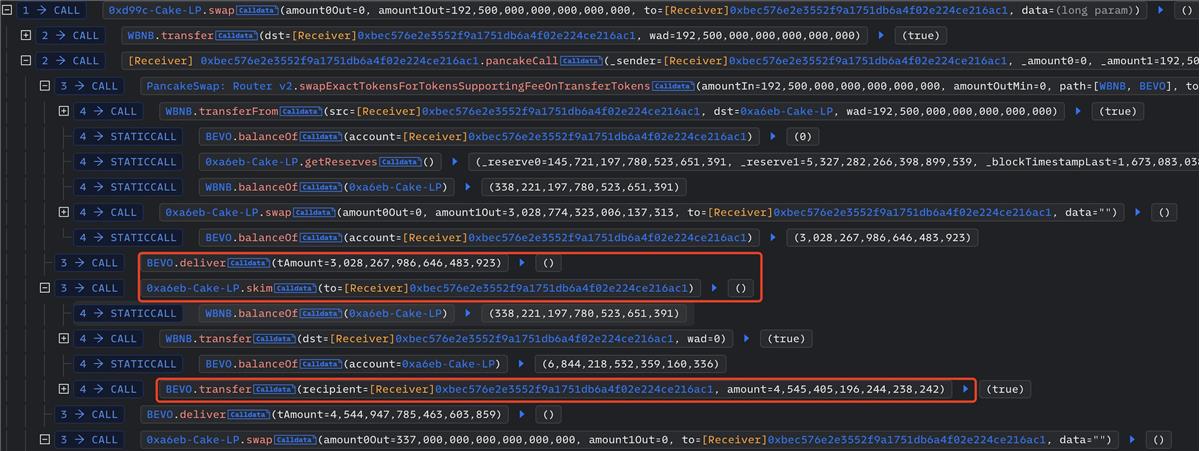

The attacker first calls the deliver function to burn their own tokens, reducing rTotal and increasing the ratio. Consequently, the reflected token values rise, making token.balanceOf(address(this)) larger than reserve.

Thus, the attacker can call skim to withdraw tokens equal to the difference and realize a profit.

A real-world attack case: BEVO NFT Art Token (BEVO):

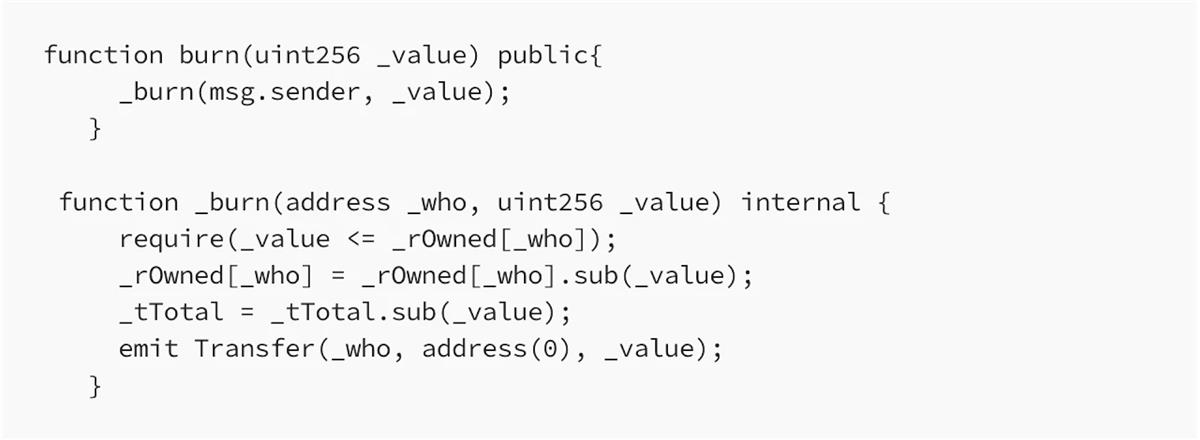

When a token contract includes a burn function, another similar attack vector emerges:

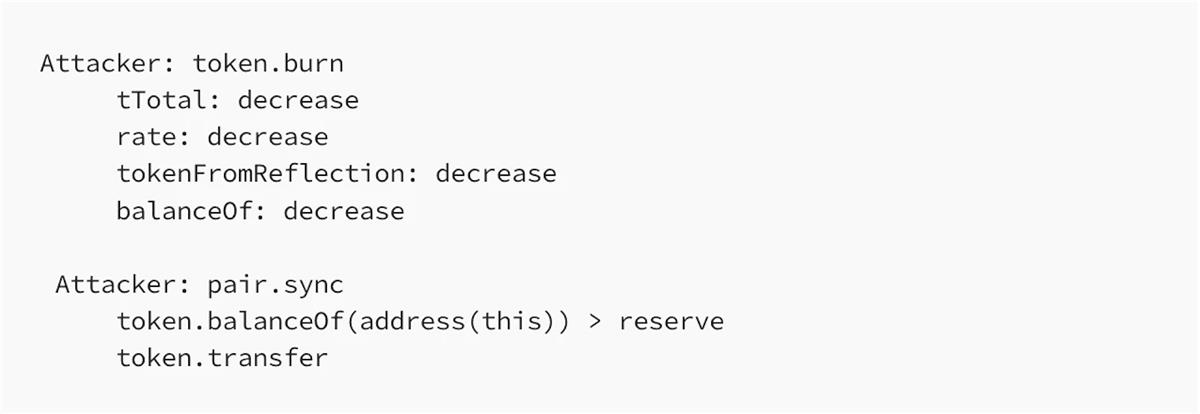

When a user calls the burn function, their tokens are destroyed and tTotal decreases, lowering the ratio and thus reducing the reflected token amounts. As a result, the liquidity pool’s effective token balance drops, driving up the price.

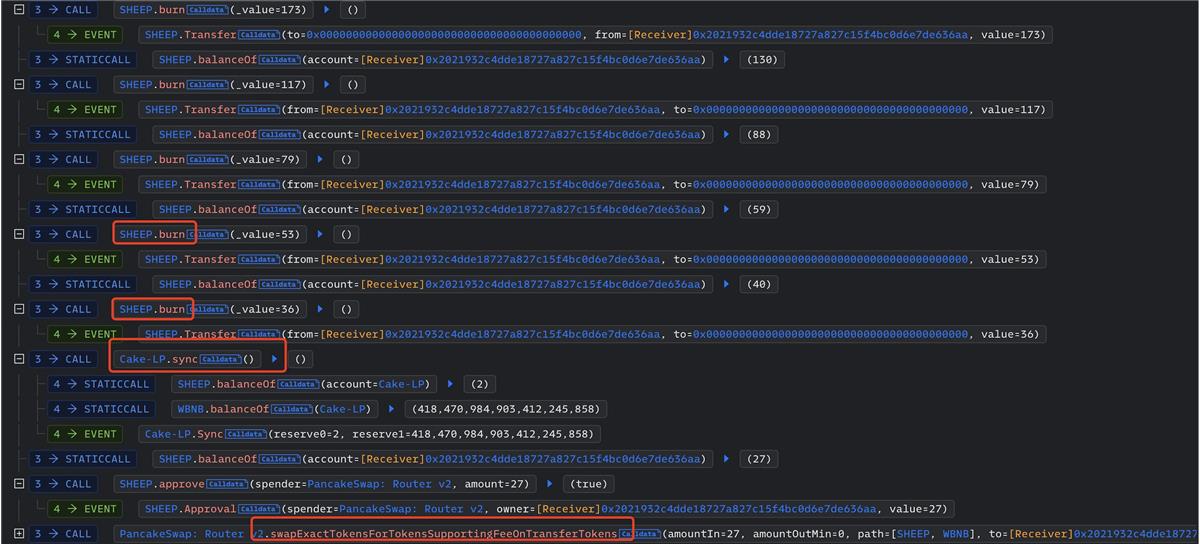

Attackers exploit this by repeatedly calling burn to reduce tTotal, then invoking the pool’s sync function to update reserves and balances. Eventually, the number of tokens in the pool drastically decreases, spiking the price. The attacker then sells their tokens for profit.

A real-world attack case: Sheep Token (SHEEP):

Defense Strategies

By analyzing the attack methods targeting burning and reflection mechanisms, it becomes evident that attackers manipulate the liquidity pool’s price. Therefore, adding the liquidity pool address to a whitelist—exempting it from token burns and excluding it from the reflection mechanism—can prevent such attacks.

Conclusion

This article analyzed two implementation mechanisms of deflationary tokens and the respective attack vectors against them, concluding with corresponding solutions. When writing smart contracts, project teams must carefully consider how tokens interact with decentralized exchanges to avoid such exploits.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News