How to design an exquisite and sophisticated recursive proof scheme?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

How to design an exquisite and sophisticated recursive proof scheme?

Almost all challenges encountered in the zkRollup and zkEVM赛道 are fundamentally algorithmic problems. The reason ZKP hardware acceleration is frequently mentioned is primarily because current algorithms are generally slow.

Authors: Lin Yanxi, CTO of Fox Tech; Meng Xuanji, Chief Scientist of Fox Tech

Preface: Almost every challenge encountered in the zkRollup and zkEVM赛道 is fundamentally an algorithmic problem. The reason hardware acceleration for ZKP is frequently discussed is primarily because current algorithms are generally slow. To avoid falling into the awkward situation of "insufficient algorithms compensated by hardware," we should address problems at the core algorithmic level. Designing an exquisite recursive proof scheme is key to solving this issue.

With the continuous development of smart contracts, an increasing number of web3 applications are emerging, causing transaction volumes on traditional Layer1 blockchains like Ethereum to rise rapidly and become prone to congestion at any time. How to achieve higher efficiency while still benefiting from the security provided by Layer1 has become an urgent issue.

For Ethereum, zkRollup uses zero-knowledge proof algorithms as foundational components, moving expensive computations originally executed on Layer1 off-chain, while submitting proofs of correct execution back on-chain. Major projects in this space include StarkWare, zkSync, Scroll, and Fox Tech.

In fact, zkRollup designs have very high efficiency requirements: they aim to keep submitted proof sizes as small as possible to reduce computational load on Layer1. To achieve sufficiently compact proof lengths, various zkRollup projects are improving both algorithms and architectural designs. For example, Fox has integrated the latest zero-knowledge proof algorithms to develop its own FOAKS proving algorithm, achieving optimal proof generation time and proof size.

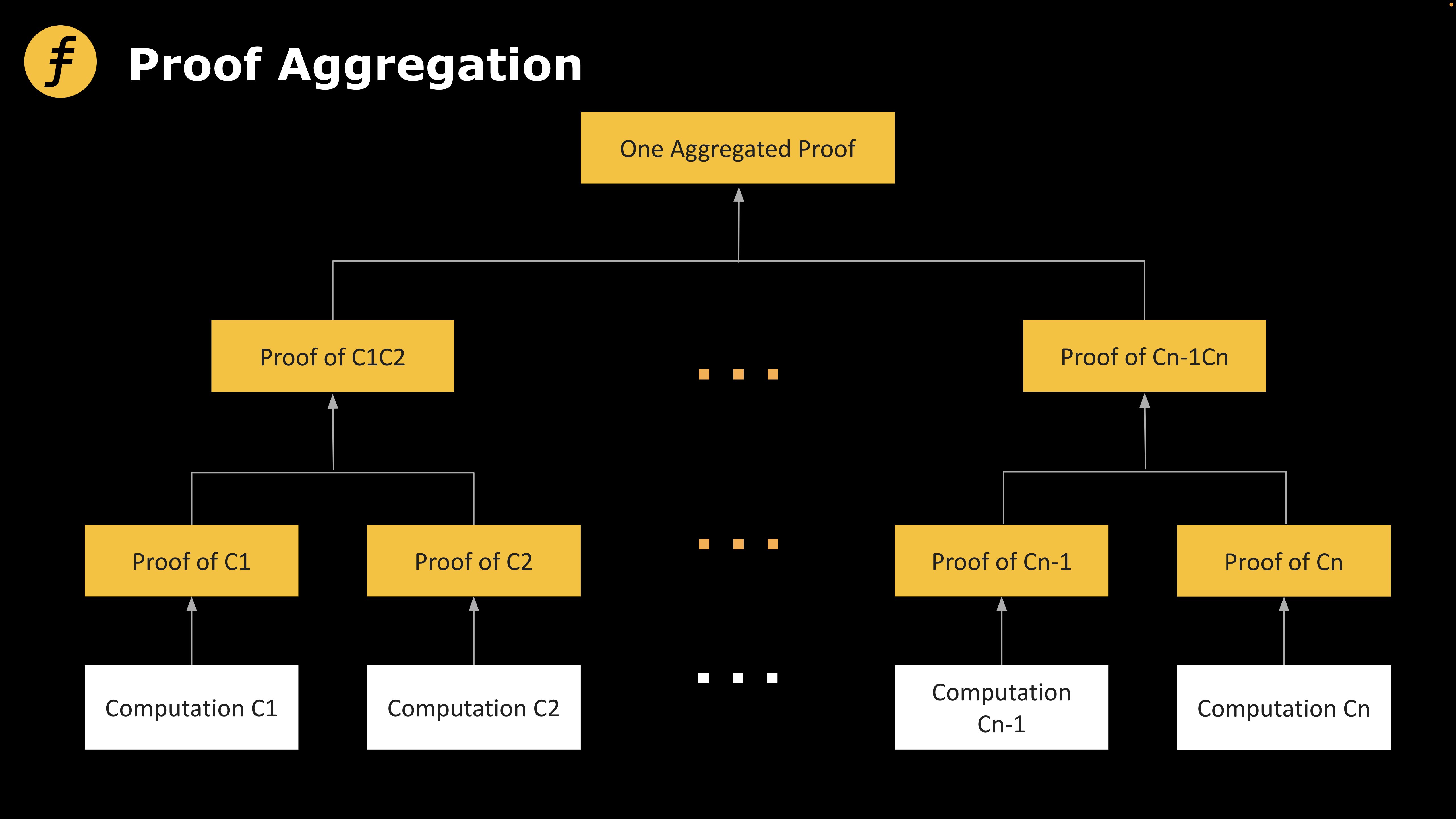

Additionally, during the proof verification phase, the most straightforward method is linearly generating and sequentially verifying proofs. To improve efficiency, a common idea is bundling multiple proofs into one—commonly known as proof aggregation.

Intuitively, verifying proofs generated by zkEVM is a linear process where the verifier must check each individual proof sequentially. However, this approach is inefficient and incurs high communication overhead. In the context of zkRollup, higher verifier-side costs mean more computation on Layer1, leading to higher gas fees.

Let’s consider an example: Alice wants to prove to the world that she visited Fox Park every day from the 1st to the 7th of the month. She could take a photo in the park each day holding that day's newspaper. These seven photos together form a proof.

Figure 1: General proof aggregation scheme

Putting these seven photos directly into an envelope represents intuitive proof aggregation, which corresponds in practice to concatenating different proofs and verifying them linearly—one after another. The problem is that this neither reduces proof size nor verification time, offering the same effect as verifying each proof individually. To achieve logarithmic-level space compression, we need to use the recursive proof (Proof Recursion) described below.

Recursive Proof Schemes Used by Halo2 and STARK

To better explain what recursive proof means, let's revisit the above example.

Alice's seven photos are actually seven separate proofs. Now consider merging them: Alice takes a photo on the 1st, then on the 2nd holds the previous day’s photo along with the 2nd’s newspaper to take another photo, then on the 3rd holds the 2nd’s photo plus the 3rd’s newspaper, and so on. On the 7th, she takes the final photo holding the 6th’s photo and the 7th’s newspaper. Others can verify from this single final photo that Alice visited the park every day from the 1st to the 7th. As we see, the original seven proof photos have been compressed into just one. A key technique here is the “photo within a photo,” recursively nesting prior photos into subsequent ones—an approach distinct from simply grouping many photos and taking a picture of them together.

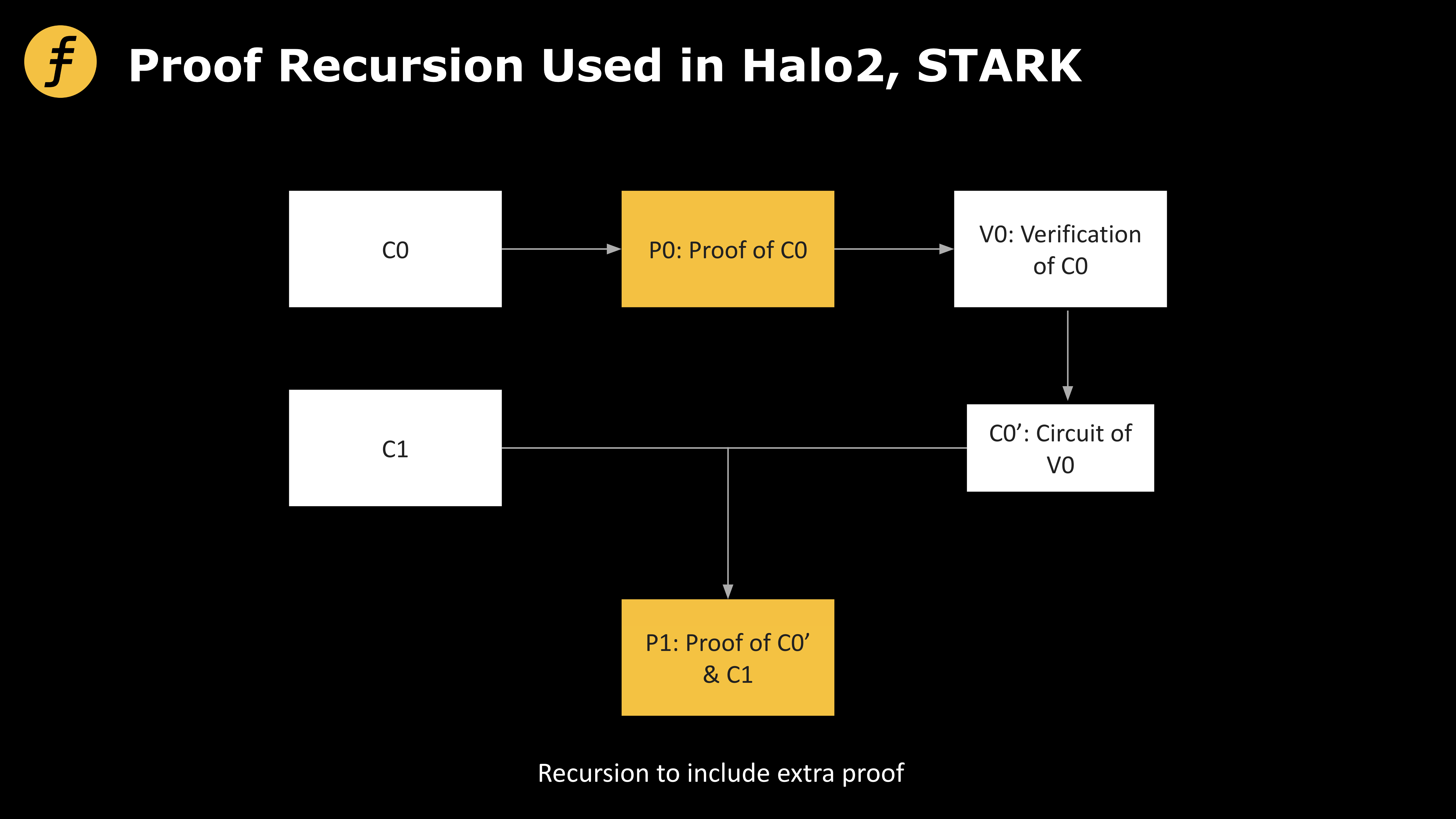

The recursive proof technique in zkRollup significantly compresses proof size. Specifically, each transaction generates a proof. Let the original transaction computation circuit be C0, P0 the correctness proof of C0, and V0 the verification process for P0. The prover transforms V0 into a corresponding circuit, denoted C0’. Then, for another transaction’s proof computation process C1, we can merge circuits C0’ and C1. Once the merged circuit’s correctness proof P1 is verified, it simultaneously verifies the correctness of both transactions—achieving compression.

Reviewing this process, the compression mechanism lies in transforming the proof verification process itself into a circuit, then generating a “proof of a proof.” From this perspective, it becomes an operation that can recurse indefinitely downward—hence the term recursive proof.

Figure 2: Recursive proof scheme used by Halo2 and Stark

The Proof Recursion schemes adopted by Halo2 and STARK enable parallel proof generation and merging of multiple proofs, allowing verification of multiple transaction executions through validating a single proof value. This compresses computational overhead and greatly improves system efficiency.

However, such optimizations remain at a layer above specific zero-knowledge proof algorithms. To further enhance efficiency, we need deeper, lower-level optimization and innovation. The FOAKS algorithm designed by Fox applies recursive thinking inside a single proof, achieving exactly this.

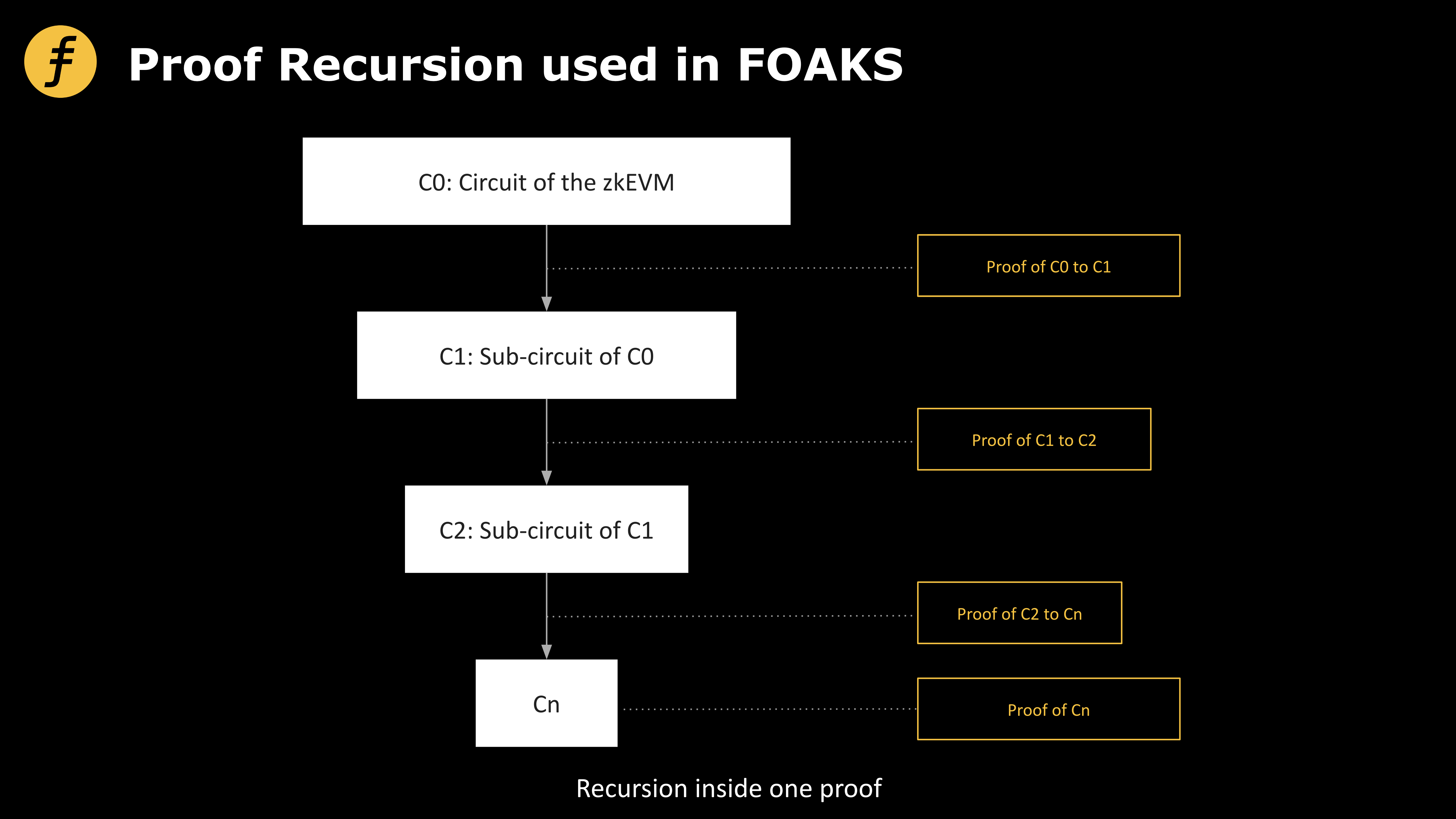

Proof Recursion Scheme Used by FOAKS

Fox Tech is a zkEVM-based zkRollup project. Its proof system also employs recursive proof techniques, but differs conceptually from the aforementioned approaches. The main distinction is that Fox applies recursion internally within a single proof. To illustrate Fox’s recursive proof method—centered on repeatedly reducing the statement to be proven until it becomes simple enough—we introduce another example.

In the earlier example, Alice proves her presence at Fox Park on a given day via photographs. Bob offers an alternative suggestion: proving Alice was at the park can be reduced to proving her phone was there. And proving that can further be reduced to showing her phone’s GPS coordinates were within the park’s boundaries. Thus, instead of taking photos, Alice only needs to send a location signal from her phone while at the park. This reduces the proof size from a full photograph (a high-dimensional data item) to a 3D coordinate (latitude, longitude, and time), effectively saving costs. While imperfect—someone might argue her phone being at the park doesn’t guarantee Alice herself was there—in actual implementations, such reduction processes are mathematically rigorous.

Specifically, Fox’s use of recursive proof operates at the circuit level. When constructing zero-knowledge proofs, we encode the statement to be proven into a circuit, then derive certain equations that must be satisfied. Instead of directly demonstrating these equations hold, we re-encode these equations as new circuits, repeating this process recursively until the final equations to be verified are simple enough to be proven directly.

From this process, we can see that this approach aligns more closely with the true meaning of “recursion.” It should be noted that not all algorithms can utilize this recursive technique. Suppose each recursion transforms a proof of complexity O(n) into one of complexity O(f(n)), and the recursion process itself has computational cost O(g(n)). Then after one recursion, total complexity becomes O1(n) = O(f(n)) + O(g(n)); after two recursions, O2(n) = O(f(f(n))) + O(g(n)) + O(g(f(n))); after three, O3(n) = O(f(f(f(n)))) + O(g(n)) + O(g(f(n))) + O(g(f(f(n)))), and so on. Therefore, this recursive technique is only effective when the functions f and g—corresponding to algorithm characteristics—satisfy Ok(n) < O(n) for some k. Fox effectively leverages this recursive technique to compress proof complexity.

Figure 3: Recursive proof scheme used by ZK-FOAKS

Conclusion

Proof complexity has always been one of the most critical factors in zero-knowledge proof applications. As the statements to be proven grow more complex, proof complexity becomes increasingly important—especially in massive ZK application scenarios like zkEVM, where it decisively impacts product performance and user experience. Among various methods to reduce final proof complexity, optimizing core algorithms is the most crucial. Building upon cutting-edge algorithms, Fox has designed an exquisite recursive proof scheme and leveraged this technology to create the ZK-FOAKS algorithm—optimally suited for zkEVM—and is poised to become a performance leader in the zkRollup space.

References

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News