Redline DAO: Why We’re Bullish on the Future of Web3 Wallets

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Redline DAO: Why We’re Bullish on the Future of Web3 Wallets

Whether it's a smart contract wallet or a personal account wallet, the private key has absolute control over the wallet. Once the private key is lost, our wallet is completely exposed to risk.

Author: Ggg, Redline DAO

-

“Not your key, not your coin.” Whether it’s a smart contract wallet or a personal account wallet, private keys have absolute control over the wallet. Once a private key is lost, our wallet becomes fully exposed to risk.

-

Private keys are the foundation of wallets; seed phrases are the recovery method for private keys—and currently represent a bottleneck in wallet development.

-

Seedless solutions enabled by MPC and social recovery are foundational for mass adoption.

-

More possibilities for future wallets—expectations around EIP-4337.

In 2010, Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin had a warlock character in World of Warcraft. One day, Blizzard decided to nerf the warlock class by removing the spell power component from Life Tap. He cried himself to sleep, and on that day realized how terrifying centralized servers could be—prompting him to leave and eventually create the decentralized network Ethereum.

In November 2022, FTX, the world's largest derivatives exchange, was exposed for misappropriating user funds. Its founder, SBF, was arrested by Bahamian police and prepared for extradition to the U.S. for trial.

From the warlock player betrayed without warning by Blizzard 13 years ago, to today’s FTX victims fighting for their rights—we increasingly recognize the importance of “Not your key, not your coin”: even with third-party audits or regulatory oversight, centralized servers can still arbitrarily alter or falsify data. On decentralized networks, however, the blockchain ledger is transparent and immutable. As long as we hold the private keys to our accounts, we maintain absolute control over our assets.

Decentralization is beautiful—but what’s the cost?

We who live in blockchain networks are the first responsible party for our own assets. When choosing a Web3 wallet, most users must make a critical trade-off: How much risk and responsibility am I willing to take for my assets? Consider traditional financial institutions:

-

Security-focused users prefer placing money in banks with complex onboarding procedures but massive scale: bank fund security (risk) > strict account setup (responsibility).

-

For convenience-driven users, keeping money in WeChat Pay or Alipay suffices. These platforms enable easy P2P transactions and require only an ID card and phone number for registration—even though they’re merely listed companies, not state-backed banks: WeChat’s convenience (responsibility) > operational stability (risk).

Back to Web3: there are two ways to store assets—custodial and non-custodial wallets. Before discussing them, let’s briefly explain how wallets work:

Wallets and Private Keys

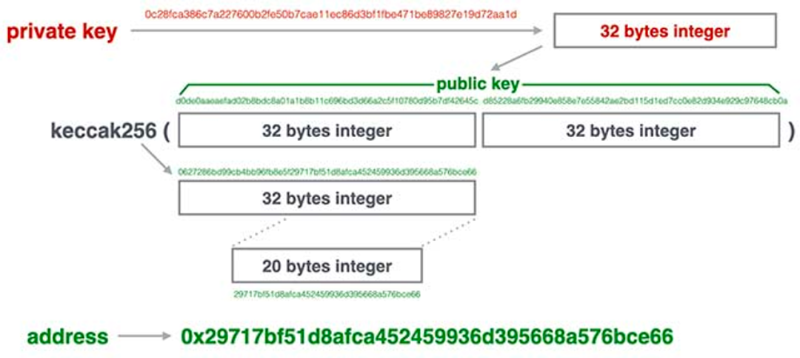

Creating an account means generating a private key. On Ethereum, there are two types of accounts: EOA (Externally Owned Account) and contract accounts (smart contracts deployed on-chain via EOAs):

-

Take the EOA account as an example,

EOA address

-

A 256-bit random number is generated as the private key. Using SHA3, the corresponding public key is derived. Then, using keccak-256 hashing (taking the last 20 bytes of the raw hash), we obtain an address uniquely tied to this private key. During this process, the private key generates 12 mnemonic words, which can later be used to re-derive the private key.

-

Currently, most mainstream dApp wallets across major blockchains are EOA wallets—such as MetaMask, Phantom (Solana), BSC Wallet (BSC), Keplr (Cosmos).

2. Smart contract accounts are pieces of EVM code deployed on-chain via an EOA account, capable of executing various functions. Unlike EOAs, contract accounts don’t have private keys and cannot initiate actions themselves—they can only be invoked by an EOA. Thus, the ultimate control of a smart contract wallet lies with the private key of the EOA used to deploy it. At this level, even smart contract wallets are ultimately controlled by private keys. Any wallet whose address is a contract is a smart contract wallet.

Smart contract wallets fall into two categories: multisig wallets and account abstraction wallets:

-

Multisig wallets: Since 2013, multisig has been the top choice for fund organizations. Initially developed in the Bitcoin ecosystem, excellent multisig wallets now exist on Ethereum (e.g., Gnosis Safe). The Ethereum Foundation itself uses a 4-of-7 multisig wallet (a smart contract holding funds, controlled by seven EOA addresses—only when at least four sign, can a transaction proceed).

-

Account abstraction allows a single EOA to control a contract address, simulating EOA behavior through smart contracts. Popular projects like Argent and Loopring belong to this category.

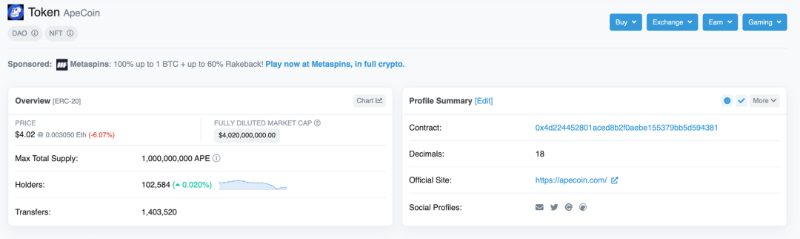

Apecoin Contract Address

3. After account creation, any on-chain activity requires the involvement of the private key.

-

According to teacher Liao Xuefeng:

In a decentralized network, no trusted institution like a bank exists. To conduct transactions between nodes, a mechanism for secure trading under zero-trust conditions must be established.

Suppose Xiao Ming wants to transact with Xiao Hong—one way would be for Xiao Hong to claim Xiao Ming sent her $10,000. Clearly, this isn't trustworthy.

Another approach: Xiao Ming claims he sent Xiao Hong $10,000. If we can verify this statement indeed came from Xiao Ming and confirm he actually owns $10,000, then the transaction is valid.

How do we verify Xiao Ming’s claim?

-

A digital signature created by a private key enables verifiers to authenticate the originator. Anyone can use the public key to validate both the digital signature and transaction result. Since only Xiao Ming—with his private key—can generate such a signature, we can trust the authenticity of the claim.

-

On Ethereum, such transactions include not only P2P transfers but also interactions with smart contracts.

-

Thus, daily wallet usage involves calling upon the local private key stored within the wallet platform to perform on-chain signing.

Wallet Security, Usability, and Censorship Resistance

Everything about wallets revolves around private keys.

At its core, a wallet is a tool that:

1. Creates private keys,

2. Stores private keys,

3. Uses private keys,

4. Backs up private keys,

5. Recovers private keys.

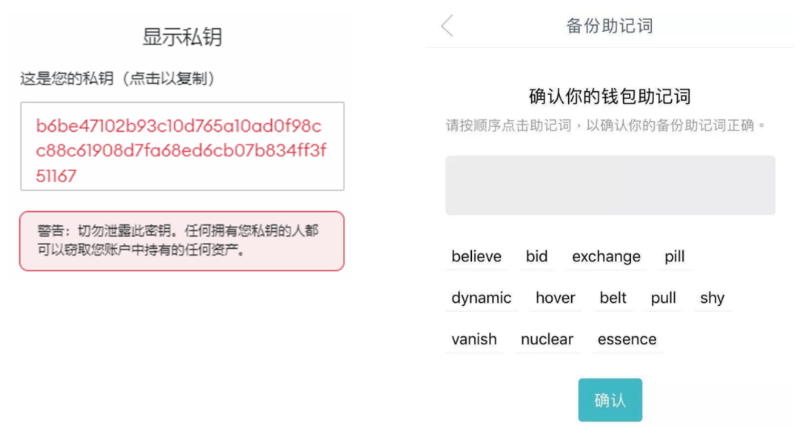

The current standard backup/recovery method is the seed phrase—a set of 12 or 24 randomly generated words shown during wallet setup:

-

Seed phrases allow derivation of the plaintext private key. When migrating a wallet to a new device, users simply input the seed phrase into the app to regenerate the private key and regain access.

-

To users, private key = seed phrase—but conceptually, they differ: the seed phrase is merely a backup/recovery mechanism for the private key.

-

Analogy: A seed phrase is like making a copy of your house key. If you lose your original, you can recreate it using the backup.

Since the private key is our sole credential for interacting with blockchain networks, safeguarding our private key and seed phrase is our responsibility. The most secure way to create an account would be offline, manually running code to generate a random number (private key) and applying SHA256 algorithms to derive the address. But this barrier is too high for average users. Therefore, when selecting a wallet, users must weigh three factors: security, usability, and censorship resistance:

-

Security: How difficult is it for hackers to crack the wallet’s private key or seed phrase?

For hardware wallets, attackers can only steal keys via phishing or physical theft.

-

Usability: How user-friendly is the wallet?

MetaMask requires users to record 12 seed words during registration and re-enter all 12 when switching devices. In contrast, Binance Exchange allows email-based login and device migration with one click.

-

Censorship Resistance: Does ultimate control reside with the user?

If a wallet app uploads plaintext seed phrases to its server, hackers could compromise the server and steal funds. Even without attacks, there remains the risk of insider theft—as seen with Slope, failing true censorship resistance.

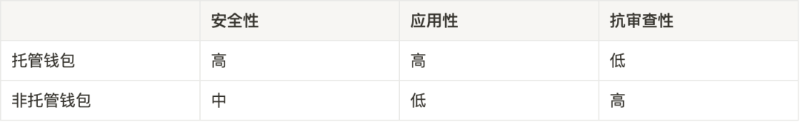

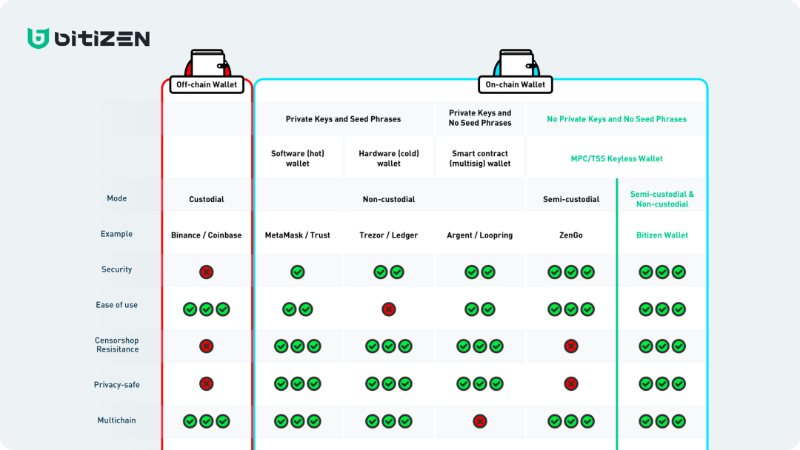

Wallets primarily fall into two categories: non-custodial and centralized custodial wallets.

- Non-custodial wallets: Users self-manage their seed phrases.

a. Take MetaMask—the most popular example. It is a non-custodial (or self-hosted) cryptocurrency wallet. Non-custodial means MetaMask stores no wallet data; private keys remain locally on the user’s browser or mobile app. When signing on-chain activities, MetaMask calls the private key from local storage. If both the private key and seed phrase are lost or stolen, MetaMask cannot help recover them—assets will be permanently lost.

b. Hardware wallets (e.g., Ledger), widely considered the safest option, generate private keys and addresses offline via dedicated hardware. The public key is imported into web wallets like MetaMask. Signing requires offline confirmation via the hardware device. Because private keys never touch the internet, stealing them is extremely hard. However, if the seed phrase is lost or compromised via phishing, the protection fails—assets can still be stolen.

- Custodial wallets

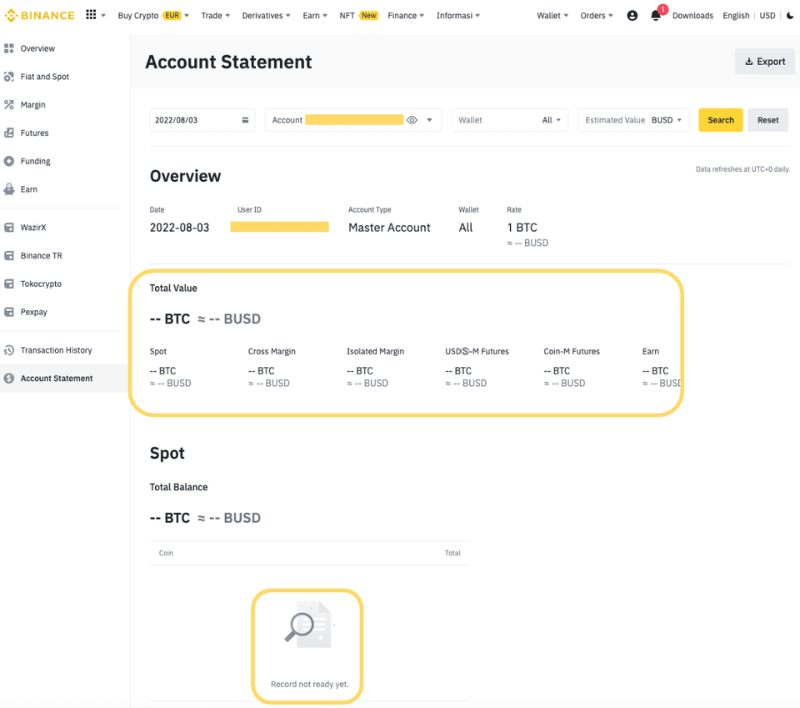

Exchange wallets like Coinbase/Binance operate as custodial wallets. The difference: the displayed balance in Coinbase isn’t a user-held private key—it’s just an internal accounting entry, not actual on-chain assets visible on Etherscan. Users trust Coinbase to hold their assets rather than self-custody. Hence, Coinbase accounts cannot interact with dApps like Uniswap.

Source: Binance

Overall, custodial wallets involve project teams managing seed phrases. Setup and recovery are easy, but security depends on the provider—not the user—and providers retain actual control. Non-custodial wallets give users full control over seed phrases. While setup and recovery are harder, they offer superior security and censorship resistance.

Flaws in Seed Phrase Recovery

As Web3 advances, growing demand and use cases emerge. The on-chain ecosystem flourishes—especially after DeFi Summer 2021 attracted many users previously confined to exchanges. By March 2022, MetaMask reached 30 million monthly active users. Yet, the dominant recovery method—seed phrases—has become hackers’ primary target. For regular users, common theft scenarios include clipboard copying of seed phrases or falling victim to phishing sites that steal locally stored private key files.

-

When attacking, hackers assess cost versus reward. All private keys (12-word mnemonics) are subsets of a dictionary. Exhaustively trying every combination could yield all on-chain assets. But the return-on-investment is poor—if brute-forcing all combinations,

-

Current standard seed phrases consist of 12 English words drawn from a 2048-word list: 2048^12 = 5.44e39 combinations (5444517870735000000000000000000000000000);

-

Achieving such computational power would already enable a 51% attack on Bitcoin;

-

Thus, hackers find higher ROI in phishing for seed phrases or stealing private keys stored locally on devices.

Continuing with MetaMask as an example, hackers can obtain saved seed phrases or private keys in two places:

- Seed Phrase

a. After wallet creation, users must securely store the generated seed phrase—ideally written by hand on paper. Some may lazily copy-paste into documents or even WeChat chat logs.

b. If malware is installed on the user’s phone or computer, monitoring the clipboard, it can capture newly created seed phrases. For instance, QuickQ VPN was found to copy clipboard content and steal seed phrases.

- Private Key

a. MetaMask typically encrypts and stores the private key locally for quick access. For Chrome extensions:

i. Storage location on Windows: MetaMask private key path:

C:\Users\USER_NAME\AppData\Local\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Local Extension Settings\nkbihfbeogaeaoehlefnkodbefgpgknn.

ii. On Mac: Library>Application Support>Google>Chrome>Default>Local Extension Settings>nkbihfbeogaeaoehlefnkodbefgpgknn

b. Thus, MetaMask’s security depends on Chrome’s security. Once Chrome’s firewall is breached, hackers gain access to encrypted private keys, decrypt them, and transfer all assets. This is why hardware wallets offer better security than plugin wallets like MetaMask.

Beyond MetaMask, some non-custodial wallets fail to achieve strong censorship resistance. For example, the Solana-based Slope wallet breach: when creating Phantom wallets, Slope’s mobile app sent seed phrases via TLS to their Sentry server, storing them in plaintext—meaning anyone accessing Sentry could retrieve user private keys.

There are numerous other wallet security incidents worth reflecting on:

EOA Account Theft

-

Fenbushi Capital founder’s wallet hacked:

Shen Bo’s wallet was compromised due to leaked seed phrase. At the time, he used Trust Wallet. Stolen assets included approximately 38.23 million USDC, 1,607 ETH, 720,000 USDT, and 4.13 BTC.

-

Wintermute suffered an attack resulting in ~$160M loss. Cause: Wintermute used Profanity to generate vanity wallets (starting with 0x0000000) to save gas fees:

Profanity was designed to help users generate visually appealing addresses—like those starting or ending with special characters. Some developers also use it to generate addresses beginning with multiple zeros.

After obtaining the initial 32-bit private key (SeedPrivateKey), Profanity iterates it using a fixed algorithm up to 2 million times (per 1inch disclosure) to collide desired addresses. Given the public key, one can exhaustively search SeedPrivateKey and Iterator values. Computation effort is roughly 2^32 × 2 million—achievable within hours/days using powerful GPUs.

Contract Account Theft

-

Paraswap’s contract deployment address hacked:

According to Slowmist’s report: Hacker address (0xf358..7036) obtained private key permissions for ParaSwap Deployer and QANplatform Deployer. The hacker withdrew $1,000 from ParaSwap Deployer and tested transfers to/from QANplatform Deployer. Our AML analysis revealed additional thefts from The SolaVerse Deployer and several other premium addresses. So far, over $170,000 has been stolen.

-

Ronin Bridge was attacked in March this year, losing 173,600 ETH and 25.5 million USDC:

Hackers fabricated a fake company, contacted Axie’s senior engineer via LinkedIn and WhatsApp, lured him with a job offer—including interviews and generous compensation—but delivered a malicious document, successfully infiltrating the Axie system and stealing the private key of the engineer’s EOA used to deploy contracts.

Besides being hackers’ main target, the seed phrase model also presents a high barrier preventing new users from entering Web3.

-

During wallet creation, users must manually write down 12 words for security. Ideally, avoid taking photos. Even using trusted open-source password managers (like 1Password), convenient copy-paste is risky due to clipboard vulnerabilities.

-

Recovering the wallet—i.e., switching devices—requires retrieving that paper and re-entering all 12 words.

Relying on a piece of paper with 12 words sounds unreliable and un-web3: we dream of living in the metaverse, yet our account security hinges on a sheet of paper invented in the Song Dynasty. These steps alone deter most Web2 users, who expect one-click logins via Google or Apple IDs.

Seedless Account Recovery Solutions

To lower wallet barriers and attract more users to Web3, we need Web2-like social login methods without sacrificing security or censorship resistance. Thus, we require more convenient and secure recovery mechanisms. Current discussions point toward one ultimate goal: seedless wallets. Two implementations exist: MPC and social recovery.

-

MPC方案: Private keys jointly computed by multiple parties, avoiding single-point failure from loss or theft.

Think of MPC as a 3FA system—each authentication method holds a key shard. There’s no single master key. If one shard is lost, others can restore it.

-

Social recovery: Store funds in a smart contract controlled by an EOA wallet, designate trusted third-party guardians. If the EOA private key is lost, guardians change contract control—eliminating the need to store seed phrases.

Community discussions often conflate social recovery with account abstraction. Note: Social recovery is a standard/function on smart contracts, proposed in EIP-2429 (2019), allowing guardians to replace contract control keys. Recently debated EIP-4337 concerns account abstraction—we’ll discuss it later.

MPC Solution

The MPC solution involves multiple parties co-generating private key shards during EOA wallet creation. In 2019, at CRYPTO 2019, the paper "Two-Party ECDSA from Secure Two-Party Computation" brought MPC into broad awareness. MPC stands for Secure Multi-Party Computation.

-

Multi-party computation (MPC) is a branch of cryptography originating nearly 40 years ago from Andrew C. Yao’s pioneering work. With MPC, private key generation no longer happens at a single point. Instead, a group of mutually distrustful parties (n parties) collectively compute and hold shares of the key (n shards)—a technique known as DKG (Distributed Key Generation).

-

Distributed key generation can support various access structures: standard “t out of n” setups (requiring t of n shards to sign) tolerate up to t arbitrary failures without compromising security.

-

Threshold Signature Scheme (TSS) refers to the combination of DKG and distributed signing.

-

When a key shard is lost or exposed, MPC supports recovery and replacement—maintaining account security without changing addresses.

MPC eliminates exposure of complete private keys throughout creation, usage, storage, backup, and recovery. By having multiple parties jointly generate and hold key shards under a “t-out-of-n” TSS scheme, MPC offers greater convenience, security, and censorship resistance compared to single-point key generation/handling wallets like MetaMask—security rivaling hardware wallets.

- Security

a. No private key / seed phrase: During wallet creation, each party (project team and user) uses MPC to generate their own key shards. The full private key never exists anywhere—true keyless design.

b. Greatly increased hacking cost: Even if attackers compromise the user’s device, they only get a key shard. Only by breaching both the service provider’s server and the user’s device simultaneously can assets be stolen.

- Usability

Social login: Users can register accounts via email or other identity verification (assuming a 2/2 signing scheme requiring both shards).

Censorship resistance:

Centralized entities (wallet provider or backup device) hold only partial key shards—cannot control user accounts.

Social Recovery Solution

Social recovery operates on smart contract wallets—essentially deploying a fund management contract on-chain via an EOA. Like any smart contract, the deploying EOA holds control authority.

-

Smart contract wallets aren't keyless—the controlling EOA still has a private key;

-

But social recovery enables changing the signing private key;

-

Social recovery is like getting a new key when yours is lost—your guardian replaces it.

Two years after EIP-2929, Vitalik first introduced social recovery use cases in a forum post in 2021:

-

During smart contract wallet setup, users can designate other EOA addresses as “guardians.” Guardian addresses must sign on-chain confirmation, paying gas fees;

-

User’s EOA serves as the “signing private key,” authorizing transactions;

-

At least 3 (or more) guardian EOAs—cannot approve transactions but can change the “signing private key.” Changing keys also requires guardians to pay gas fees for confirmation;

-

The signing private key can add or remove guardians—but changes require a delay period (typically 1–3 days).

-

In daily use, users interact with socially recoverable smart contract wallets (e.g., Argent, Loopring) just like regular wallets—using their signing key for fast, single-confirmation transactions, similar to MetaMask:

a. Creating Private Key

Account abstraction wallets create keys identically to MetaMask.

b. Storing Private Key

Since the controlling EOA is only used as a “signing private key” and control can be transferred via guardians, users don’t need to specially protect seed phrases.

c. Using Private Key

○ Contract wallets execute transfers/transactions via contract calls, thus costing more than MPC or traditional wallets;

○ But because they invoke contracts, they support paying gas fees in non-native tokens (e.g., USDC/USDT instead of ETH). This significantly lowers interaction barriers for new Web3 users: technically, the project swaps USDC for ETH within the same transaction to cover gas fees.

d. Backing Up Private Key

Account abstraction wallets replace seed backups with “guardians”—but this is counterintuitive and costly:

① New Web3 users registering wallets must find three trusted friends already in Web3 with EOA wallets, asking them to spend gas to become guardians;

② If users compensate friends’ gas costs via three transfers, setting up one wallet incurs six gas payments—whereas MPC wallets cost nothing to create.

e. Recovering Private Key

If users lose their signing key, they can request social recovery. Contact guardians to sign a special transaction (user or guardian pays gas) updating the registered signing public key in the wallet contract. This is simple: guardians visit a site like security.loopring, review recovery requests, and sign.

However, in terms of private key security, it doesn’t match MPC wallets:

-

Attack cost: Hackers can still steal the full private key by compromising the user’s device. In short, smart contract wallets only add one extra recovery option when keys are lost.

-

Low censorship resistance: Since social recovery requires designated “guardians,” collusion among guardians poses risks.

-

Main risks of social recovery:

① Collusion: If users know they’re part of someone’s recovery circle, they might exploit it;

② Targeted attacks: External actors aware of recovery owners may target the weakest link;

③ General exposure: Attackers infecting large-scale dependencies may gain access to multiple identities, indirectly affecting unaffected users via recovery mechanisms.

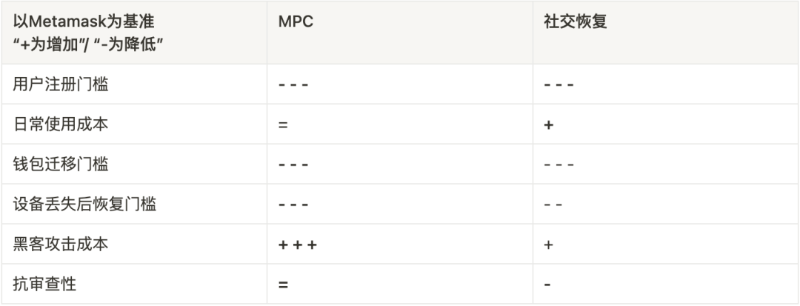

MPC vs. Social Recovery: Security, Usability, Censorship Resistance.

The Future of Mass Adoption: Web3 Wallets

With seedless recovery solutions, we envision next-gen Web3 wallets—those registrable and accessible via email. We analyze representative MPC and account abstraction wallets: both achieve low-barrier, seedless access. Now we evaluate them based on security and censorship resistance:

#Bitizen

Among MPC wallets, Bitizen achieves thorough anti-censorship and usability using a 2/3 TSS scheme. Let’s analyze its security and censorship resistance:

- Security

a. Creation

To ensure strong censorship resistance, after wallet registration, users can back up key shards to a second device via Bluetooth—implementing a 2/3 TSS scheme: Bitizen server, user’s primary device, and secondary device.

b. Storage

No complete private key is ever generated during setup—hence no seed phrase. User’s Bitizen account links to their cloud drive and email. Login via email enables normal wallet usage.

c. Usage

① Users authenticate via facial recognition to retrieve cloud-stored and locally stored key shards for signing (2/3 required);

② Once backed up via Bluetooth, the second device can remain fully offline and unused (signing only requires Bitizen server and main device).

d. Backup

① Locally stored key shards are backed up to the user’s cloud drive;

② When switching devices, users simply log in via email and facial verification. Bitizen retrieves the backed-up key shard from the cloud.

e. Recovery

① If the user loses their device or deletes the local Bitizen file, they can restore the key shard from the cloud;

② If unable to access the cloud, Bitizen reconstructs the key shard using the server-held shard and the user’s secondary backup device, restoring normal functionality.

Source: Bitizen

- Censorship Resistance

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News