Bixin Ventures: The Censorship Resistance of Bitcoin and Ethereum

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Bixin Ventures: The Censorship Resistance of Bitcoin and Ethereum

Ultimately, the characteristics of decentralization, censorship resistance, and sovereignty independence are goals that Bitcoin, Ethereum, and many other blockchains strive to achieve.

Original Title: "Censorship resistance in Bitcoin and Ethereum"

Authors: Allen Zhao, Mustafa Yilham, Henry Ang & Jermaine Wong, Bixin Ventures

Translation: Evan Gu, Wayne Zhang, Bixin Ventures

In early August, news that the U.S. Department of Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) had decided to add Tornado Cash to its sanctions list brought the issue of censorship resistance into sharp focus. To avoid potential legal liability, RPC service providers Alchemy and Infura restricted access to Tornado Cash smart contract data, while Circle (issuer of USDC) blacklisted wallet addresses on the sanctions list. These blacklisted addresses were also blocked by DeFi protocols such as Aave, although users can still interact with some smart contracts—albeit through additional steps requiring technical expertise.

This raises a broader question: Can blockchains be censored at the protocol level? There are growing concerns within the Ethereum community about censorship at the protocol level, with 66% of beacon chain validators post-merge showing sensitivity to OFAC regulations. If more than one-third of validators (by stake weight) engage in any form of censorship, the Ethereum network would cease to function properly.

In this article, we will compare BTC (PoW) and ETH (PoS) on their censorship resistance across three key questions, followed by our concluding thoughts.

Defining "Censorship"

In a recent Bankless podcast, Justin Drake defined two types of censorship:

Weak censorship: Occurs when certain block producers exclude individual transactions from blocks, degrading user experience. For example, a compliant block producer may reject transactions from blacklisted addresses, but those transactions could still eventually be included by non-censoring producers.

Strong censorship: Happens when an individual’s transaction is never included on-chain. Since the user effectively loses the ability to transact, this can be considered an actual loss of assets. This scenario may occur if the network is taken over by a majority—commonly known as a 51% attack—and could threaten the very existence of the blockchain.

In the following discussion, we will use Bitcoin and Ethereum as representative networks for PoW and PoS systems, respectively. We’ll first identify the factors contributing to censorship risk and then examine how each network resists censorship.

Question 1: Could jurisdiction-based regulation lead to weak censorship due to miner/validator centralization?

Both Bitcoin and Ethereum face issues of pool and validator centralization. This creates a risk that mining pools or validator operators could be compelled to comply with regulations and censor transactions deemed illegal within their jurisdictions.

Ethereum

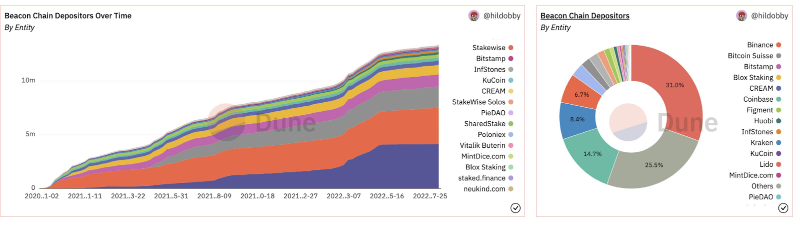

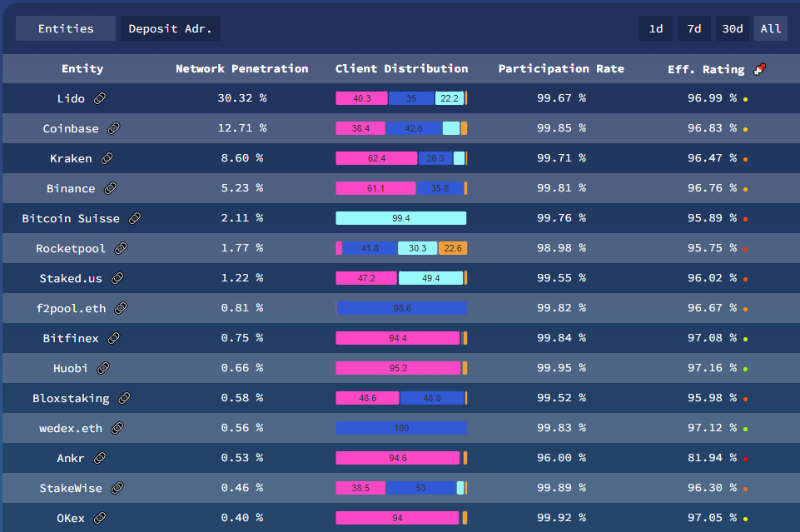

Since The Merge, the top two staking service providers collectively hold 43.03% of the stake, and the top three hold 51.63%. The risk here is that if Lido and Coinbase collude, they could halt the network; if Kraken joins them, they could fully take control of Ethereum.

Source: Related Network

Before discussing how Ethereum mitigates centralization risks, it’s important to understand why validators have become centralized. Under Ethereum’s PoS mechanism, block producers choose which transactions to include in the next block and determine their order. This enables participation in MEV (Maximal Extractable Value) extraction—a concept well-defined by Amber in their recent article on the ETH merge.

“Maximal Extractable Value (MEV), broadly speaking, refers to the residual value validators or miners can extract across a series of blocks given available actions. These actions include reordering transactions, censoring blocks, or even attempting to reorganize the blockchain. Common forms of MEV include sandwich attacks, arbitrage, and liquidations.”

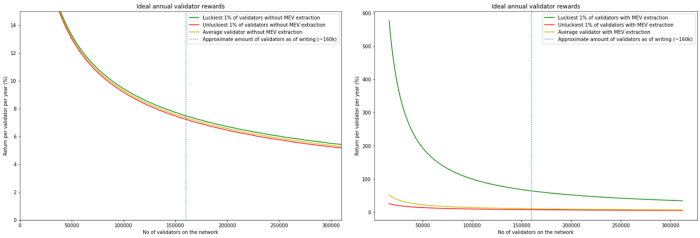

Source: Flashbots

As shown in the chart, validator rewards increase significantly when MEV is factored in. Due to these economic incentives, larger players operate more validators, pushing out individual and non-professional participants. As a result, ordinary holders tend to join staking pools via services to earn higher and more stable returns, increasing validator centralization.

Another factor contributing to stake centralization is cryptocurrency exchanges. Exchanges remain the primary gateway for users to acquire Ether. Given their large user bases, significant amounts of ETH naturally accumulate there. Their convenient staking platforms further encourage consolidation. Users should be educated about the risks of using centralized staking platforms—for instance, the potential for malicious behavior under regulatory pressure.

Although staking pools are not ideal, they allow more ETH holders to participate and thus contribute positively to Ethereum’s decentralization.

So how does Ethereum address censorship risks from centralization?

Solution 1: Separating Block Proposers from Block Builders

A widely discussed solution is Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS). PBS decouples the roles of block proposer and block builder, allowing validators to earn MEV rewards without needing to run complex operations, thereby reducing centralization pressures.

Three key participants in the blockchain ecosystem can balance each other to mitigate and ultimately eliminate censorship.

Specialized **builders** maximize MEV and transaction fees by ordering transactions and then pay a fee to **proposers** to include their proposed blocks on-chain. Thus, builders with censoring intent cannot publish transactions without proposer cooperation.

**Proposers**, also known as validators, either select the most profitable block or refuse to propose any block. If they suspect a builder is censoring transactions, they can instead propose a censorship-resistance list (**crList**). As long as the block isn’t full—or if their block wasn’t selected—the builder must include these transactions. Since EIP-1559 has been implemented, over 80% of blocks contain spare gas space, meaning users who pay priority fees above base fees should generally get their transactions included. In short, proposers can maximize profits by selecting the highest-paying blocks but retain the ability to enforce inclusion via crList.

**Attesters** monitor the block-building process and only attest to a proposer’s block if it includes the highest-paying block. This prevents malicious proposers from censoring transactions.

While the above greatly improves validator decentralization, it doesn’t solve builder centralization. How to decentralize builders is beyond this discussion, but you can read more here.

Solution 2: Encrypted Mempool

Another research direction is encrypted mempools to counter centralized censorship. Users encrypt transactions before broadcasting them to the mempool, and decryption only occurs once the transaction is included in a block. This prevents potential censors from accessing transaction content during block construction. It also helps prevent MEV abuse like front-running. Another benefit: encrypted mempools could eventually solve builder centralization. In such a model, proposers could build their own blocks by selecting the highest-fee transactions from the encrypted mempool, bypassing reliance on complex external builders.

Bitcoin

Bitcoin is often hailed as “digital gold,” a label reflecting both its role as digital store of value and its censorship resistance. While less programmable than Ethereum—limiting MEV opportunities—Bitcoin still faces increasing geographic concentration of miners. Mining requires specialized hardware and energy, making it capital-intensive. As a result, the industry has evolved toward shared resources, where miners pay service fees based on computing power, reducing cash flow burdens compared to independent investment.

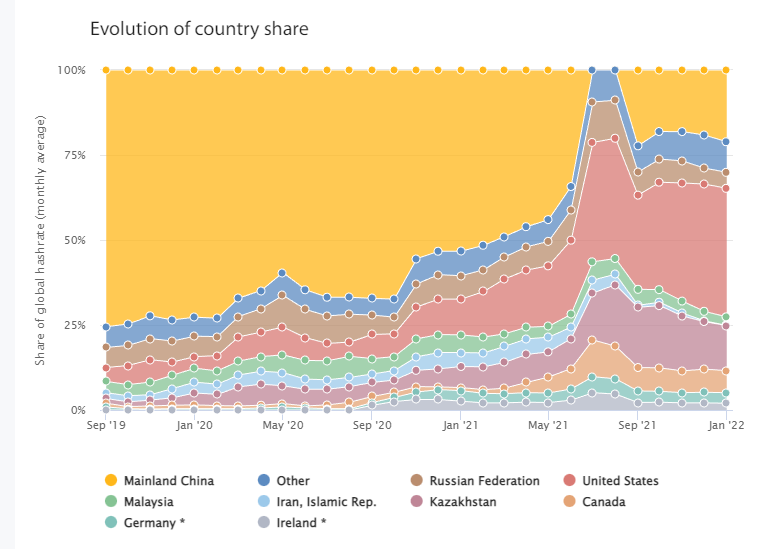

Source: Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index

As shown above, prior to China’s 2021 ban on crypto mining, Chinese miners accounted for over 45% of global hash rate. Hash rate has since shifted to the U.S., which now accounts for 38% globally as of January this year. Mining companies may be forced by local regulations to reject certain transactions, creating a censorship threat.

How does Bitcoin address censorship risks arising from mining pool centralization?

Solution 1: Switching Mining Pools

When a mining pool operator complies with censorship rules contrary to miners’ interests, miners can easily switch to another pool (e.g., relocating away from censored pools). Because mining uses on-demand computing power, miners need only change the pool address in their mining software to migrate. During China’s 2021 crackdown, miners rapidly relocated overseas and switched to offshore pools, restoring and even surpassing previous hash rate levels.

While Ethereum validators can withdraw or restake at will, time lags exist due to withdrawal cooldowns and queuing systems.

Solution 2: Giving Miners More Control Over Block Construction

Most Bitcoin miners direct their hash power to pools, communicating via the Stratum v1 protocol, which coordinates hash creation and submission. If pools collude to censor transactions, the community has no recourse. However, Stratum v2 allows miners to select their own transaction sets, giving them greater control over block construction and resisting censorship by malicious pool operators.

For more information on Stratum v2 and its security and revenue upgrades for miners, read here.

Solution 3: Free Market Competition

Bitcoin supporters argue that PoW mining incentives are the best defense against transaction censorship. As block rewards halve over cycles, transaction fees will approach 100% of miner income. Even if compliant pools or miners censor paid transactions, miners in other jurisdictions will eagerly capture those transactions. Ultimately, compliant pools or miners will lose market share and profitability in a free market.

Conclusion 1: Bitcoin handles censorship from centralization in block production better than Ethereum.

Today, Bitcoin is better equipped to handle centralized censorship during block construction. If a mining pool censors transactions, miners can immediately switch pools, significantly enhancing their autonomy.

While Ethereum has viable solutions to censorship, they remain largely in research and not yet implemented, as development priorities are diverted by competition with other programmable blockchains.

Question 2: Could low network security budgets lead to strong censorship risks?

Low security budgets increase the risk of 51% attacks. An attacker gaining control could block incoming transactions, reorder new ones, and even rewrite blockchain history to reverse their own transactions—enabling double-spending.

Ethereum’s Security Budget

A successful 51% attack on Ethereum could allow attackers to censor all new deposits or withdrawals, making recovery difficult. Therefore, token distribution should be decentralized to prevent coercive acquisition of sufficient tokens for an attack. At the time of writing, 13.6 million ETH is staked on the beacon chain. Ethereum’s economic security can be estimated as 13.6M ETH × price × 51%, representing the minimum cost to censor transactions. At $1,700 per ETH, this equates to approximately $11.5 billion today. In reality, costs would be much higher due to non-linear price increases driven by rising ETH demand.

Given that such funds may be accessible to certain organizations or nations, preventive measures are still necessary.

Solution 1: Encourage More Users to Stake

Currently, only 11% of ETH is staked—compared to 77% on Solana, 66% on Cosmos, and 65% on Avalanche—indicating substantial room for growth. Increasing staking makes it harder for attackers to amass 51% of total stake.

However, a barrier to wider staking is the opportunity cost of DeFi yields. If users earn better returns in DeFi, financial incentives may outweigh staking rewards. Liquid staking protocols offer one solution, though they reintroduce centralization risks like those seen with Lido. Although Lido distributes stakes among roughly 30 whitelisted validators, the approval process remains under Lido’s control. Therefore, the criteria and mechanisms for adding or removing validators are critical, requiring strong governance within DAOs.

Encouragingly, Lido is exploring dual-governance proposals, where key votes involve both stETH and LDO holders, aligning incentives. On censorship-related matters, if LDO holders pass an initial proposal, stETH holders are also involved. If consensus fails, they retain the right to exit. Read here for detailed explanations of voting mechanics and outcomes.

Solution 2: Diversify Validators to Prevent Coercive Governance Capture

If ETH cannot be acquired on the market, another way to gain network control is coercing 51% of validators. Validator diversity enhances censorship resistance through:

Jurisdictional/geographic diversity to ensure no single country can force validators offline

Operator/stakeholder diversity to make coercive censorship extremely difficult under broad stake distribution

Client diversity to prevent a single client bug from taking validators offline

Lowered hardware requirements so anyone can run a validator as needed

Increased number of validators with full transaction copies

Solution 3: Social Layer Intervention

If prevention fails, Ethereum can intervene at the social layer. Specifically, upon detecting censorship, a fork process would automatically initiate, with time reserved for consensus. Ideally, full nodes would identify censoring chains by checking mempools and fork accordingly, penalizing censoring chains—all without social coordination.

However, forks are rarely quick or automatic. Censorship might be accidental—e.g., due to validator client bugs. Distinguishing real censorship from errors is crucial. Other considerations include: which chain to adopt, checkpoint selection, how to punish attackers on the new chain—all impacting the chain’s economic value. New users must understand how to extract funds if joining an uncensored fork. While no formal guidelines exist, governance and decision-making must remain as decentralized as possible.

Bitcoin’s Security Budget

Under strong censorship, miners could mine all rewards and reorganize the chain at will. With the current hash rate of 230M TH/s, an attacker would need over 230M TH/s to control the network (assuming honest miners don’t participate). Using the most efficient ASIC chip today, Antminer S19 PRO (110 TH/s), this requires about 2.09 million units (230,000,000 ÷ 110). At $4,400 per unit, the hardware alone would cost $9.2 billion, excluding energy costs.

Solution 1: ASIC Acquisition Difficulty Makes Bitcoin More Censorship-Resistant

While the cost may be feasible for powerful actors, acquiring ASICs faces major hurdles—only a few companies manufacture them, and annual supply is limited, preventing rapid attacks.

Solution 2: Low Miner Switching Costs Enhance Bitcoin’s Decentralization

Acquiring enough hardware to control the network is extremely difficult, so attacks may target existing mining pools via coercion. This can be countered by the emergence of geographically diverse mining pools, which lower switching costs and enable rapid migration under censorship, enhancing resistance.

Conclusion 2: Bitcoin is more resilient than Ethereum against 51% strong censorship attacks. Ethereum’s reliance on the social layer as a last resort gives disproportionate power to a few, raising unresolved social consensus issues.

On the surface, Ethereum’s security budget exceeds Bitcoin’s. Yet, the barriers to acquiring hardware for Bitcoin are greater than those to acquiring a majority of ETH tokens.

If attackers attempt to seize control via centralized mining pools, Bitcoin’s solution is simpler: honest miners can rebalance hash rate by switching to non-attacking pools.

In Ethereum’s case, while social intervention is possible, many questions remain about transitioning via user-activated soft forks. How do non-attackers reach social consensus? Does the new minority decide? Or the core team? The process resembles an “Ethereum DAO” vote. Should decisions be made by voter majority or stake majority? A common critique of DAO voting is that while most holders may vote one way, a single large holder can override them. This isn’t meant to reflect actual fork processes, but to highlight unresolved governance issues in Ethereum’s social layer. Ultimately, as Nic Carter noted, the social consensus layer inevitably opens space for politicization—Ethereum may suffer the same fate as expropriating national governments.

Thus, we believe Bitcoin is more resilient. That said, this may not always be true. A potential future scenario: as block rewards trend toward zero, if Bitcoin transaction activity doesn’t rebound, lack of fees could impair miner solvency. Miners might shut down, lowering hash rate and weakening Bitcoin’s security budget. Therefore, Bitcoin must continue attracting new users to remain a healthy network.

Question 3: Could External Dependencies Introduce Censorship Risks to the Base Layer?

Stablecoins

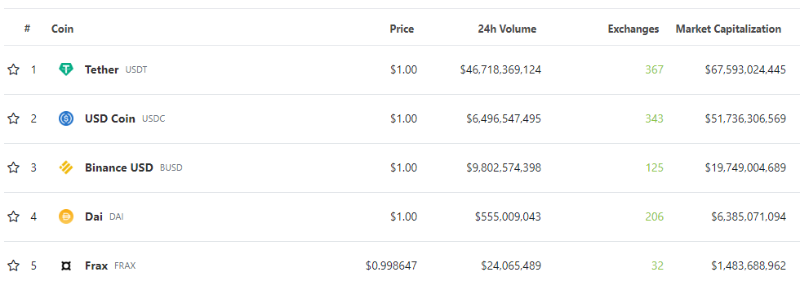

All cryptocurrencies are denominated in stablecoins—Bitcoin and Ethereum included. A quick look at stablecoin market caps shows the top three are backed by fiat collateral held by centralized custodians. This places them under regulatory scope, raising concerns: what if custodians, under government pressure, prevent users from redeeming stablecoins into fiat? Though unlikely, the ripple effects would be severe. Recently, Circle, issuer of USDC, froze over $75,000 worth of USDC linked to Tornado Cash addresses per OFAC sanctions.

Potential Solution 1: Overcollateralized Stablecoins

Users can mint a fiat-pegged token by locking up crypto collateral. MakerDAO’s DAI is currently the largest decentralized stablecoin in crypto. When asset prices fall, it maintains the 1 DAI = 1 USD peg by liquidating the crypto collateral. Having weathered Bitcoin and Ethereum price swings since 2017, it has proven robust. However, it still holds over 30% of its collateral in USDC. After recent events involving USDC and Tornado Cash, it is now undergoing governance discussions on whether negative interest rates are needed to make DAI truly neutral and public infrastructure.

Another option favored by Vitalik is RAI from Reflexer. Here, users deposit ETH and mint RAI up to 2/3 of the ETH’s value. Crucially, RAI does not maintain a fixed dollar peg—its value floats based on market volatility. It also supports negative interest rates, helping stabilize fluctuations. Read here for a detailed explanation of how RAI works.

However, a fundamental issue with overcollateralized stablecoins is that they permanently remove liquidity from the market—not ideal if we expect financial activity to move on-chain.

Bitcoin feasibility: Bitcoin is nearly ideal collateral. But even with existing solutions, overcollateralization removes liquidity—an undesirable outcome if on-chain finance is the goal.

Ethereum feasibility: ETH-backed stablecoins may not be viable. If ETH faces censorship, redemption issues arise as users seek to exit positions. Using Bitcoin as collateral reduces correlation risk, but liquidity removal remains a concern.

Potential Solution 2: Algorithmic Stablecoins

Despite Luna’s collapse tarnishing their reputation, algorithmic stablecoins remain an alternative—aiming to create pegged tokens without collateral, using governance tokens instead. Arbitrage between the governance token and stablecoin maintains the peg. But such systems are fragile, relying on rational actors and unwavering confidence in the governance token.

Once confidence breaks, a death spiral ensues: as the governance token price falls, market participants sell rather than stabilize, accelerating the decline.

Theoretically, algorithmic stablecoins could function like parts of the traditional banking system without extracting liquidity. But no current project adequately mitigates systemic risks.

Bitcoin feasibility: Not applicable—no viable candidates in the market.

Ethereum feasibility: Not applicable—no viable candidates in the market.

Potential Solution 3: Bitcoin or Ethereum as Decentralized Stablecoins

Thought experiment: What if Bitcoin became an uncensorable, decentralized “stablecoin”? This might resolve issues faced by both Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Bitcoin feasibility: Seems feasible—1 BTC = 1 BTC. This could address declining security budgets due to low transaction activity (recall: block rewards → 0 ⇒ miner income depends on fees ⇒ need sufficient activity to stay solvent and maintain high hash rate). If BTC is widely used on Ethereum (and other programmable chains), transaction volume from DeFi and apps could sustain miner incentives, strengthening resistance to attacks.

Ethereum feasibility: Imagine a fork triggered by censorship of USDC or USDT, leaving no fiat-pegged stablecoins on-chain. How many users would choose a “bubble-like, low-volume” stablecoin? Using Ethereum as a decentralized stablecoin eliminates reliance on fiat-pegged tokens, making chain forks more viable under strong censorship. Users wouldn’t fear economic collapse, as Ethereum’s base-layer currency has strong anti-censorship properties.

RPC Networks

RPC (Remote Procedure Call) networks are vital to blockchains. They provide node access, enabling users to interact with blockchains while engaging with standalone programs. Running RPC nodes requires specific hardware, so most developers rely on centralized RPC networks like Infura and Alchemy for dApp API needs. The downside: these centralized networks can restrict blockchain data access to comply with jurisdictional laws and act as single points of failure vulnerable to attacks. The result: users may face service disruptions, severely degrading UX.

Solution 1: Light Clients

Ethereum encourages more users to run light clients. These don’t store full chain state history but sync via sync committees. They can query network state directly from full nodes instead of relying on centralized Infura or Alchemy.

Bitcoin also promotes light clients. These interact with the network without storing the full blockchain, querying interested blocks and transactions from other nodes.

Solution 2: Decentralized RPC Networks

Decentralized RPC providers incentivize distributed nodes to serve blockchain data to apps and users. Using a decentralized set of RPC nodes eliminates single points of failure, enhancing base-layer security and censorship resistance. Existing solutions include Pocket Network, Ankr, and Solana’s GenesysGo. Both Ethereum and Bitcoin would benefit from decentralized RPC layers, especially given the vast number of applications relying on RPC networks—this would strengthen Ethereum’s censorship resistance.

Core Developers and Project Teams

The arrest of Tornado Cash founder Alexey Pertsev sparked debate on whether developers or project teams can be held liable for open-source code. Should they remain anonymous? Easily identifiable identities place individuals under jurisdictional reach, making them susceptible to regulatory control. While there’s no clear requirement for founders or developers to be accountable for their code, ensuring geographically distributed teams may be wise to resist targeted censorship from specific jurisdictions.

Conclusion 3: External dependencies significantly impact base-layer protocol censorship resistance.

We believe the primary issue to address is the choice of base-layer currency. Both Bitcoin and Ethereum’s economic value are tied to USDC and USDT—both vulnerable to U.S. regulations. For other censorship risks—such as RPC layers and protocol developers—we believe existing solutions can mitigate and eventually eliminate these threats.

Conclusion

While we’ve conducted an extensive comparison between Bitcoin and Ethereum, each with unique features and solutions, Bitcoin’s characteristics make it well-suited as a base-layer currency. Yet, we still need the programmability of blockchains like Ethereum to support on-chain applications. Ultimately, decentralization, censorship resistance, and sovereign independence are goals shared by Bitcoin, Ethereum, and many other blockchains striving toward a more resilient future.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News