How to properly conduct token distribution?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

How to properly conduct token distribution?

Why do founders always allocate tokens to VCs in incorrect proportions?

Author: Vader Research

Translation: Arena Wang, TechFlow

Why do founders often allocate tokens to VCs at incorrect ratios?

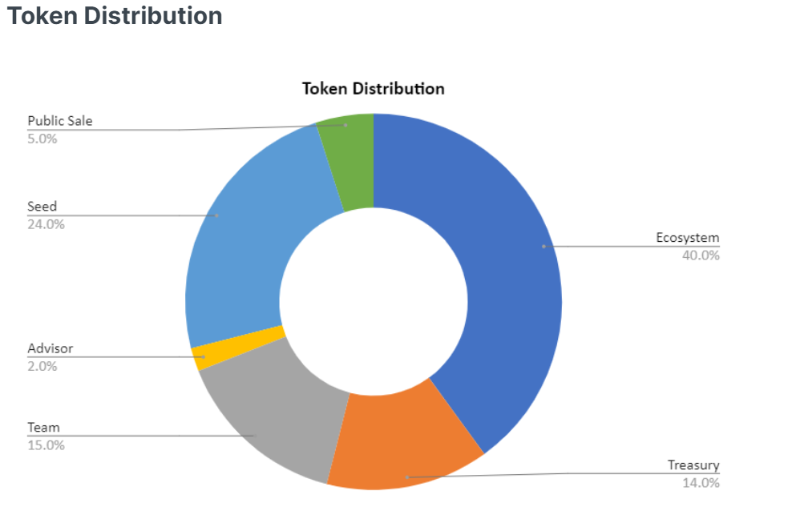

We typically use a pie chart to illustrate a project’s token allocation structure, clearly showing the proportions allocated to the team, investors, treasury, and community.

Usually, this allocation ratio is determined jointly by the proportion of non-investor tokens and the ratio between team and investor allocations.

GuildFi Token Allocation: 29% investors, 17% team, 14% reserve, 40% community.

When a project raises funds, it must decide how much of its token supply to allocate to equity investors. At this stage, determining the correct token allocation ratio is extremely difficult.

Currently, there is no established framework to help founders determine an accurate token allocation ratio when structuring their cap table. This often leads to inappropriate allocations between the team and different types of investors.

In this article, we will cover:

-

Estimated value;

-

Token value model;

-

Equity-owned token value model;

-

Token & equity shared value model;

-

Conclusion.

Estimated Value

Before diving in, let’s first clarify the relationship between equity and tokens.

There are various valuation models; we categorize them as follows:

1. Token Value Model (all estimated value belongs to tokens);

2. Equity-Owned Token Value Model (team tokens allocated to equity entities);

3. Token & Equity Shared Value Model.

The key point here is estimated value: the actual value of an asset should equal its estimated value. Value arises where revenue exists. Any metric that can be converted into future income (e.g., transaction volume, user count) can influence value.

If a game charges a 5% fee on secondary market transactions and these revenues go to token holders, they can collectively vote on how to use the proceeds. Token holders may reinvest the revenue back into protocol development (marketing, hiring, new product R&D) or distribute it to themselves (token buybacks, staking rewards). Therefore, the intrinsic core value of the token is primarily driven by business revenues, and this value can accumulate in any currency—including the issuer's own token.

The Sandbox

Likewise, if a decentralized exchange has $10 billion in daily trading volume but fees flow only into the equity entity’s income, then the DEX’s governance token holds almost no fundamental value.

Take another example: a DEX with $10 billion in daily volume hasn’t started charging fees yet—because it subsidizes trades to attract users. But if the DEX later decides that fee revenues will go solely to equity, then its governance token also loses fundamental value.

Sushiswap

The factor influencing each token’s core value is business revenue: the ratio of token vs. equity value determines the token’s fundamental valuation.

Fundamental valuation methods are far more complex (e.g., DCF) and involve many special cases (e.g., asset-based valuations), but at a very high level, “revenue = estimated value” is a robust heuristic.

In traditional financial markets (equities, bonds, commodities, forex), most investment capital is managed by institutional investors—professionals in securities analysis and fund management. Institutional investors build complex models to evaluate every tradable asset and propose a valuation range reflecting a company’s intrinsic value based on assumptions and prevailing fear/greed sentiment over a given time horizon.

However, in crypto markets, most investment capital is managed by retail/unsophisticated investors who do not prioritize a project’s commercial fundamentals like institutions do, as evidenced by the popularity of Dogecoin, Shiba, Luna Classic, and NFT PFPs.

Therefore, crypto markets may not reflect true intrinsic fundamental value as quickly as traditional financial markets. However, with increasing institutional capital flowing into crypto, this is expected to change within the next 24–36 months.

Model 1: Token Value Model

Let’s consider a scenario: founders raise funds and plan to issue tokens to incentivize active protocol participants. Tokens give these participants a sense of ownership over the protocol, further enhancing loyalty, retention, and engagement.

This could be a game rewarding the most engaged players, a DEX/lending platform rewarding liquidity providers, a decentralized social network rewarding top content creators, or a blockchain rewarding validators. Token incentives can also be seen as a user acquisition/retention tool.

To encourage long-term holding of rewarded tokens by protocol participants, the token’s intrinsic value should be tied to future business revenues. If all protocol revenues go to equity rather than tokens, what drives token value? Why would active participants hold these tokens instead of selling immediately? Smart participants won’t hold tokens less useful than memecoins—they know such tokens will eventually collapse.

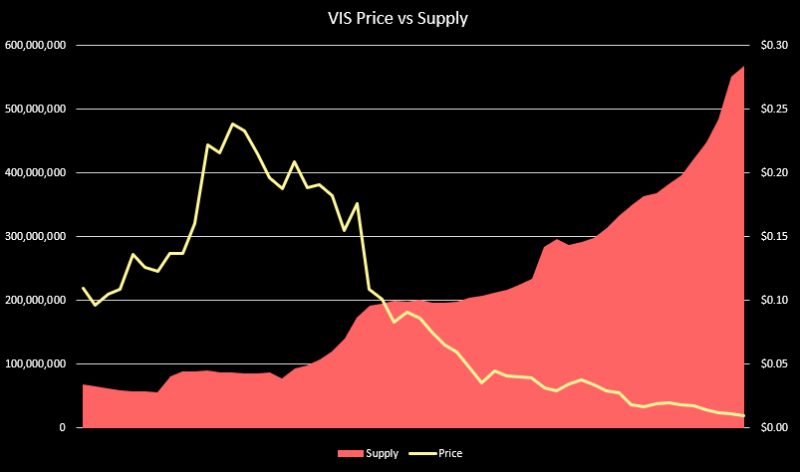

This also damages smart contract reputation. Most crypto market participants monitor token prices in real-time; when prices consistently decline, people suspect an imminent crash. Since token supply increases over time to reward participants, without sufficient demand to balance this growing supply, the token price will inevitably fall.

Hence, founders might consider allocating all value to the token. This way, token incentives distributed to participants carry higher dollar value, reflecting the protocol’s future success potential. It gives participants a rational reason to hold rather than sell. This better converts users into loyal users, and loyal users into evangelists.

But if all value created by the protocol flows to tokens, what drives equity value? More importantly, does equity become worthless?

Even though equity retains legal rights, it may become economically worthless. To provide equity investors with greater flexibility in valuation and economic modeling, founders should allocate tokens to equity investors in addition to issuing shares.

But what theoretical percentage of tokens should equity investors receive? If a seed investor invests $1 million for 10% equity (implying a $10 million post-money valuation), should they also receive 10% of the tokens?

No—they should receive less than 10%, say 8%, 5%, or 3%.

Judgment should be based on the following factors:

i) Current and future equity fundraising rounds;

ii) Treasury reserve percentage in token allocation;

iii) Community percentage in token allocation;

iv) Public token sale.

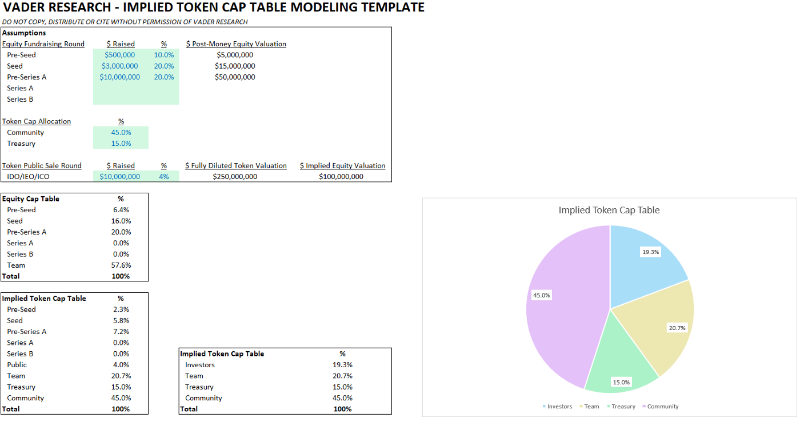

Vader Research Token Cap Table Model

We’ve built a model that calculates token cap table allocations based on the above parameters. These inputs are highlighted in green, enabling founders and investors to use the numbers to assess appropriate token distribution. Click here to download the model.

A video explaining how to use the model, the logic behind the calculations, and how to set the parameters is available here.

Why is it so important to align token cap table allocations with equity cap tables? Any misalignment could lead to future conflicts among teams, investors, and communities. Founders and investors need a rough framework and model to guide token allocation discussions. We hope this model becomes a reference point for future token allocation negotiations.

The token cap table differs from the equity cap table.

-

Every time a team raises equity funding, new shares are minted out of thin air, diluting existing shareholders.

-

Conversely, when raising funds via tokens, no new tokens are minted. Instead, tokens are drawn from a finite reserve within the token smart contract.

Model 2: Equity-Owned Token Value Model

Model 2 shares the same valuation framework as Model 1, but team-held tokens are fully owned by the equity entity. This resembles the structural relationship between Sky Mavis and the AXS token. Since value flows directly to tokens rather than equity, the rationale is that equity derives value through token ownership. This aligns incentives between tokens and equity.

There are two ways to apply this model:

1. Investors own both equity and tokens;

2. Investors own only equity.

Investors Own Both Equity and Tokens

Investors own both equity (whose value is driven by token ownership) and tokens. The problem with this approach is that investors are essentially making a double bet on tokens, resulting in their cumulative token ownership exceeding their proportional equity stake.

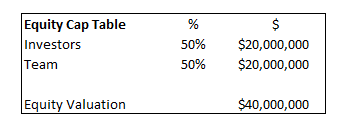

Assume investors own 50% of the equity, with the rest held by the team.

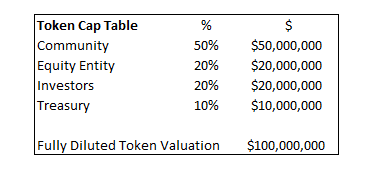

Also assume the token allocation looks like the table below, with investors receiving 20%. Note: the 20% allocated to the team goes to the equity entity, not directly to founders or employees.

Assuming equity-owned tokens (valued at $20 million) are distributed proportionally among shareholders (investors, founders, employees), investors end up with 30% of token allocation (20% directly via token cap table, 10% indirectly via equity).

Thus, the team (founders and employees) ends up with only 10% of token allocation. If only tokens have estimated value, this is a terrible deal for the team. They effectively give away more tokens than their equity cap table entitles them to.

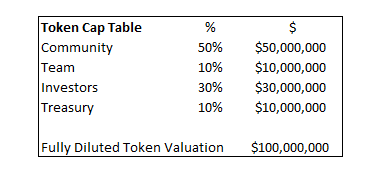

Sky Mavis and the AXS token serve as an example. Team-allocated tokens belong to the equity entity, while equity investors also received token allocations.

Early VCs investing in Sky Mavis received AXS token allocations. The 21% of AXS tokens allocated to the team actually went to the equity entity, not directly to team members. We don’t know exactly how equity-owned tokens were distributed, but it’s reasonable to assume they were allocated proportionally to shareholders.

Individual investors received only 4% allocation. We don’t know the exact details, but likely some VCs received smaller allocations than deserved, or even none at all. Overall, if the structure is balanced enough, this may not be too bad. For instance, in Sky Mavis’s case, equity investors gained rights to future tokens (e.g., RON).

Model 3: Token & Equity Shared Value Model

Here, both equity and tokens share the estimated value. This model applies across various scenarios. The portion of value allocated to tokens can vary widely depending on the business model, product, and sector.

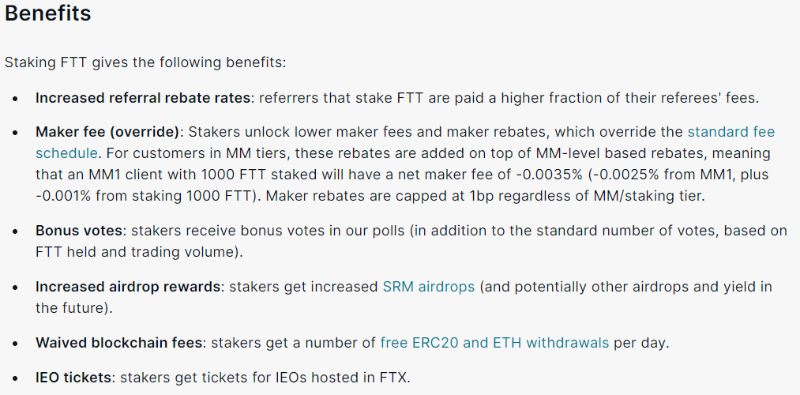

Consider FTT and BNB tokens used by centralized exchanges like FTX and Binance. These tokens grant holders benefits such as trading fee discounts. Thus, token value ties to the exchange’s future success. But unlike the first two models, only a portion of the estimated value flows to the token.

Another variation is seen in STEPN and Pegaxy’s handling of tokens.

Both follow an Axie-like economic model, but the key difference lies in Axie: AXS tokens paid for breeding are automatically burned. In other words, when a player pays $100 worth of AXS for breeding, the generated value flows to AXS holders because the circulating supply of AXS gradually decreases, driving up its price.

In contrast, in STEPN and Pegaxy, the GMT and PGX tokens used for breeding are not automatically burned. Instead, they flow into company revenue. Developers then decide whether to burn part of the tokens or conduct buybacks. From an investment standpoint, this makes GMT and PGX less attractive.

Conclusion

This article focuses on how teams with equity should decide the proportion of value allocated to tokens. We will continue exploring other token cap table topics, such as ideal treasury reserves, community allocations, liquidity pools, staking distributions, and vesting schedules.

In our next article, we’ll share a token cap table and equity vesting agreement to strengthen long-term alignment between VCs and founders.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News