Opinion | Buyback-and-Burn is a Last Resort

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Opinion | Buyback-and-Burn is a Last Resort

If it's a currency, reducing the supply would lead to an increase in the value of each unit. But for capital goods such as governance tokens, issuance is key to capitalization, while token burns may hinder the growth of fundamental value.

Source|Ethereum Enthusiasts

Author|Joel Monegro

Translation|Akasha

The common feature of the "buyback-and-burn" token model is a network that generates revenue (in some form of cryptocurrency) and periodically uses its earnings to buy back its native tokens, which are then destroyed. The intention behind this model is to increase the value of the native token by reducing its supply as revenue grows. Buybacks should help achieve this goal, but the effects of burning differ significantly between currencies and capital assets. For a currency, reducing supply increases the value per unit. However, for capital assets such as governance tokens, issuance is key to capitalization, and burning may hinder fundamental value growth.

Currency vs. Capital Assets

An asset is a currency if its value derives purely from transactional use—for example, the U.S. dollar, whose value comes solely from being usable to consume goods and services. ETH, for instance, is also a currency because you spend it to access Ethereum's services, and also to purchase other assets.

Conversely, an asset is a capital asset when its value stems from governance rights or equity participation in a resource pool. Company stock, for example, is essentially a mental construct designed to allocate power and profits.

Whenever a network earns revenue in a currency and redistributes that value to its token holders—regardless of the method—we know it is a capital asset, since its intrinsic value derives from business income streams. MKR and ZRX are prime examples: both networks earn revenue in ETH and redistribute that value to their (governance) token holders. Maker uses a buyback-and-burn model, while 0x distributes ETH proportionally to those who stake ZRX and provide market-making services on the network. Yet both are capital assets whose value is driven by fiat-currency-denominated income flows.

(Some assets can be both currency and capital asset—see Cryptonetwork Governance as Capital. In Ethereum’s transition to PoS, ETH2.0 will also become兼具both currency and capital asset characteristics.)

The Role of Buybacks

Having distinguished these two, we now turn to “buybacks.” In traditional stock markets, buybacks—when a company purchases its own shares on the open market—are a common way for large corporations to boost their stock price. Stock buybacks work because they increase existing shareholders’ proportional ownership of corporate capital. However, repurchased shares aren’t automatically destroyed; instead, they’re held by the company as treasury stock. Unlike outstanding shares, treasury stock carries no voting rights and plays no economic role within the organization. This makes sense: it would be meaningless to distribute profits to yourself, just as it would be nonsensical to buy something you already own.

By reducing the number of outstanding shares, buybacks improve certain valuation metrics (such as revenue per share), benefiting all remaining shareholders. This justifies paying a premium over market price during buybacks. But destroying treasury stock afterward has little additional effect. The buyback alone achieves the intended purpose, since what matters for pricing is how many shares participate in governance—not how many exist. Treasury shares do not participate in corporate governance.

From a governance standpoint, destruction does ensure these shares won’t re-enter circulation. However, the entity authorized to destroy treasury shares is usually the same one that can issue new shares. In Maker’s case, MKR is burned whenever revenue is earned, but MKR can also be issued during sudden solvency shortfalls (e.g., March 2020). Ultimately, token supply is governed by the social contract between governance protocols and shareholders. Thus, the protection against equity dilution offered by burning is minimal.

The key point is this: taking a certain amount of capital assets out of circulation is useful, but it works by increasing the ownership stake of holders of circulating shares—not inherently because buybacks make the asset “scarcer,” nor necessarily because the total value of the stock increases. Reducing share count may raise the stock price, but it doesn’t change the overall value of the system. The same applies to capital tokens in crypto networks: buybacks have a positive price impact, but burning does not create new value—it merely reallocates existing value among a smaller group. This is why companies that constantly buy back shares are often perceived as low-growth.

Issuance, Capitalization, and Growth

Much of crypto culture associates “inflation” with “dilution of value.” This may be true in monetary systems. But note: inflation and deflation are monetary concepts that don’t directly apply in capital markets. In capital markets, issuing governable shares is essential to capitalizing a company’s equity. Issuing stock is the cheapest way to obtain growth capital. For startups, for example, issuing stock helps founders acquire human and financial capital (talent and funding) at low cost.

Stock issuance also correlates with how you acquire resources needed for expansion. This holds even in more decentralized systems like DAOs and protocols. We can use newly issued tokens to compensate various participants and inputs across a crypto network: rewarding makers for work performed, users for ongoing purchases, and investors for capital and liquidity provision. In all cases, issuance fuels fundamental value growth by increasing the system’s capital, which eventually translates into higher token prices.

It’s not that growth is impossible without issuance—but zero issuance removes strong incentives for continuous investment into the system. As a token holder, you might prefer moderate dilution over none at all, as it encourages greater contribution. Burning tokens is worse than no dilution: it increases holders’ ownership share without requiring additional investment. Moreover, when burning fails to increase token price proportionally to the burn rate—which is most real-world cases—burning actually reduces the network’s total market cap.

Continuously reducing shares or tokens over time restricts capitalization, much like deflationary currencies discourage spending. If the burn rate consistently exceeds the rate of fundamental value growth, you effectively concentrate ownership at the expense of liquidity and long-term value, potentially leading to decapitalization of the system. Prudent issuance is far better than obsessing over “scarcity.” For example, you could reintroduce treasury assets to continuously incentivize productive capital input, sell treasury assets to raise financial capital, or use them as collateral for loans. We must abandon the idea that automatically increasing scarcity equates to greater value.

Instead of burning tokens, devise more creative ways to restructure capital cycles.

Buyback and Make

To summarize our argument: buybacks are a good way to distribute profits to capital token holders, but burning limits the network’s ability to reinvest in itself. “Buyback and Make” offers an alternative—a mechanism leveraging automated market makers (AMMs) to retain the benefits of buybacks and issuance while avoiding the downsides of burning, without permanently increasing token supply. We can implement a protocol treasury using a Balancer “smart pool” that serves simultaneously as an automated buyback mechanism, a token issuance pool, and a liquidity provider. (Translator’s note: Balancer is an automated market maker protocol.)

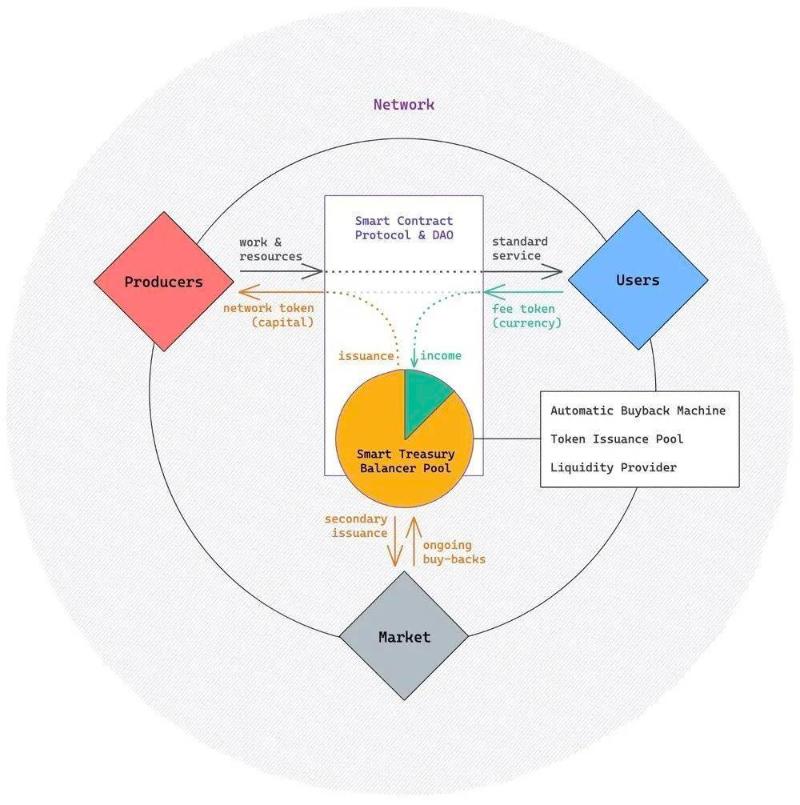

This setup resembles the “crypto-economic loop.” Protocol/DAO smart contracts coordinate production and regulate the exchange of productive and financial capital between producers and consumers. Producers contribute labor and resources (productive capital) in exchange for capital tokens, according to an issuance schedule. Users consume network services and pay using designated currencies or fee tokens. We introduce a “smart treasury” implemented via a Balancer pool, controlled by the protocol/DAO contract. Assume the network earns revenue in ETH, and its native token is called TKN.

Balancer is a programmable liquidity protocol and decentralized exchange. Simply put, you can create an index basket containing up to eight tokens. You can customize the weights of each token in the basket. In our example, we set it to 10% ETH (currency) and 90% TKN (capital token). We also configure the pool so only the controller (the protocol itself) can add or remove liquidity. Suppose we mint 10 million TKN with a hard cap and deposit some ETH into the pool. This new Balancer treasury can now perform several functions:

1. Automated buyback mechanism. Deposit all (or part) of the ETH revenue into the treasury pool. Whenever the ETH value in the treasury exceeds 10% of the basket’s indexed value, the Balancer pool automatically sells excess ETH and buys TKN on public markets until the 90/10 ratio is restored. Since the only other token in our pool is TKN, rebalancing requires buying TKN from the market (or adding new TKN to the pool). If there are no sellers, the pool automatically quotes a higher price for TKN.

Because the pool is owned by the network, this process is equivalent to a buyback—with the same positive impact on TKN’s price. As revenue flows into the network and is transferred to the smart treasury, buybacks occur in real time and are autonomously managed by the Balancer protocol. This is far more efficient, eliminating the need for developers to maintain complex buyback-and-burn code, specialized “keeper” bots, or incentive mechanisms for liquidity providers—all required under the buyback-and-burn model. Arbitrageurs already active on Balancer’s market provide these services freely and in real time, greatly simplifying the protocol.

2. Token issuance pool. The protocol can issue new tokens when capital enters the network, or mint specific amounts upon certain events and distribute them per the issuance schedule. Our model uses pre-minted tokens (though hybrid models are possible), depositing the initial allocation into the smart treasury. Since only the protocol contract can add or remove liquidity, the network can withdraw funds from the treasury to finance incentive programs requiring TKN. As in other models, the issuance schedule can be executed via smart contract.

Bonus: The reverse operation of buybacks allows the smart treasury to function as an automated capital-raising engine. Just as depositing ETH (or another fee token designated by the protocol) triggers an automated buyback, withdrawing currency has the same economic effect as releasing TKN from the treasury, selling it on the market, and converting it back to currency. This function enables continuous fundraising for expenditures when needed. For example, a DAO could withdraw currency to fund development, or a protocol could use fee tokens in the treasury as a “reserve fund” backed by its native token. This is especially useful for protocols using their own token as ultimate settlement insurance (e.g., Maker’s MKR), yet it avoids the need for special keepers or auction mechanisms to ensure newly minted tokens are sold at fair market prices—Balancer provides this guarantee at no extra cost.

3. Liquidity provider. Finally, our smart treasury can also act as a liquidity provider. Because assets in our Balancer pool can be exchanged via its decentralized exchange, buyers and sellers of TKN are guaranteed liquidity—they can always trade directly with the protocol itself—and token holders gain confidence in the economic integrity of these trades. Balancer allows us to customize pool parameters to tune the level of liquidity provided. For example:

-

Balancer pools can hold up to eight assets. In our case, we only have TKN and ETH. But if your network accepts multiple tokens as payment (e.g., ETH plus various stablecoins), you can adjust weights to enable adding or removing TKN liquidity through other tokens. For instance, create a pool with 80% TKN, 10% ETH, and 10% DAI, and deposit all revenues into it. This allows maintaining liquidity across multiple TKN trading pairs.

-

Balancer’s key innovation is its ability to maintain an indexed basket. In our case, this lets us build a pool with 80–90% TKN and 10–20% currency tokens. You can easily adjust this ratio to any desired weighting. The only impact is on the overall liquidity of TKN in the pool. Generally, a higher TKN ratio increases slippage, making the token’s price more sensitive and trades more expensive due to larger price swings.

-

We can program the pool to charge up to 10% in trading fees (collected from traders swapping tokens via our pool), thereby subsidizing the treasury. This allows programming premiums on token buys and sells. Adjusting the fee rate alters the competitiveness of the treasury pool in the broader market. To deter buyers and protect the protocol’s TKN balance, you can set a higher fee rate.

These parameters can be fixed permanently after initial setup, programmed via smart contracts, or updated through a DAO voting mechanism as needed by the network. Essentially, you’re programming how much liquidity the network provides to the market. To generate more liquidity, make trading with the treasury cheaper—e.g., by increasing the proportion of currency tokens in the pool to reduce slippage on the capital token, or by lowering trading fees. To make the network itself the final liquidity provider—the ultimate buyer and seller of last resort for TKN—raise the trading fee and slippage.

The ability for a DAO to change settings enables the network to adapt its tokenomics to shifting market conditions. For example, during bull markets, increasing the TKN balance and fee rate in the treasury may be preferable, accelerating TKN accumulation. During bear markets, TKN liquidity becomes more critical to network health, so lowering trading fees makes sense. This mirrors central banks managing economic cycles.

Bonus: Similar to automated buyback and capital-raising functions, our smart treasury can also efficiently liquidate collateral. Again, protocols like MakerDAO rely on keeper bots and incentive schemes to manage liquidations, but using a Balancer pool delivers the same functionality at no cost.

In sum, this is where the “make” in “buyback-and-make” comes from. Instead of burning tokens—an act of waste—there are better, more interesting alternatives. On one hand, the protocol can continuously draw TKN from the smart treasury to distribute as incentives. On the other, as network usage grows, all revenue flows into the pool, triggering automatic TKN buybacks. Without burning, repurchased tokens can be reissued under the same incentive model. Buyback-and-make preserves the network’s market cap, unlike burning. Plus, Balancer offers numerous features that simplify code, protocol, and mechanism design.

But my favorite aspect of this model is that it enables permanent incentive structures: continuous issuance without exceeding a fixed token supply cap. In the early stages of our network, more TKN may leave the pool than enter via buybacks. But as the network matures, inflows and outflows will balance. By recirculating repurchased tokens into perpetual rewards and liquidity, we ensure constant incentives to fund the system. This is powerful: the network can permanently enjoy the benefits of issuance alongside buybacks, all within a strictly capped token supply.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News