How can crypto projects distribute profits by learning from traditional companies?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

How can crypto projects distribute profits by learning from traditional companies?

Buybacks are becoming a popular model for crypto projects to distribute profits.

Author: Saurabh Deshpande

Translation: Luffy, Foresight News

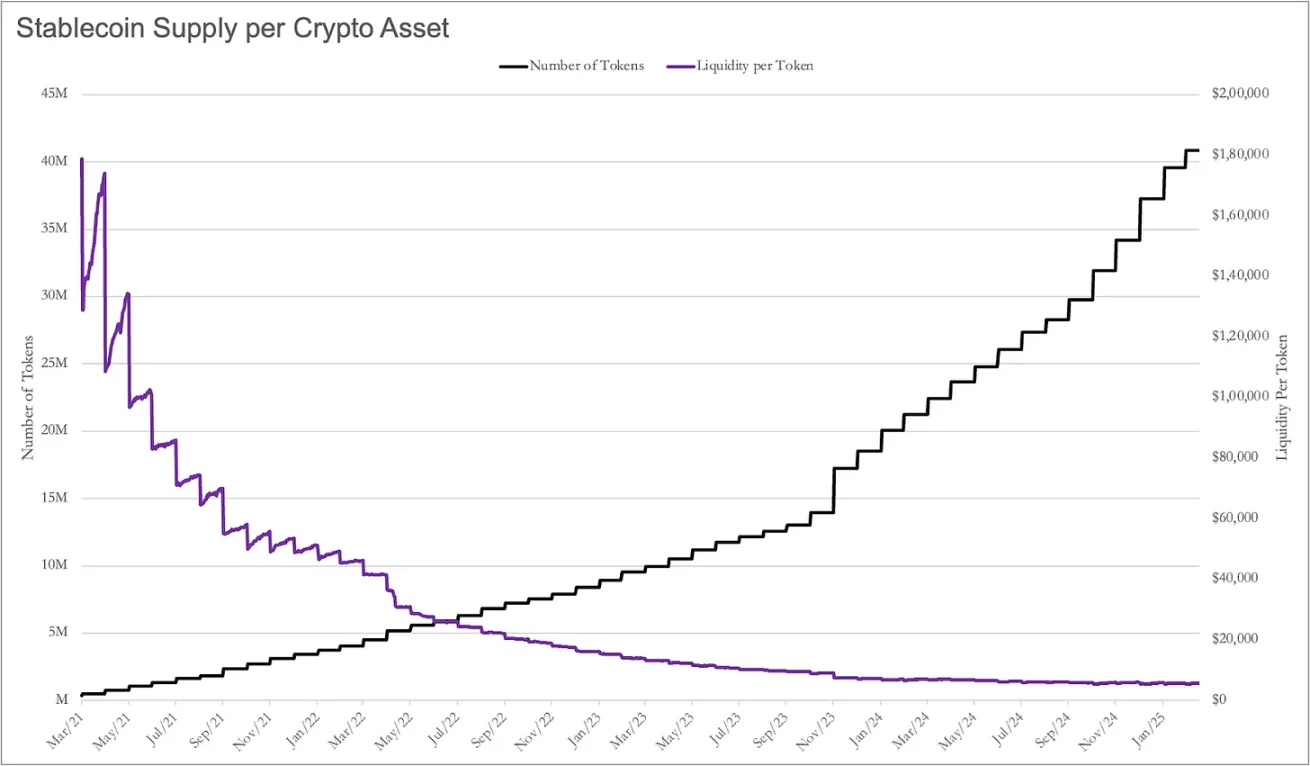

Recently, I used stablecoin supply as a proxy for liquidity and combined it with the number of tokens in the market to estimate per-asset liquidity. Unsurprisingly, liquidity trends toward zero—and the resulting chart is nothing short of an “art piece.”

In March 2021, each cryptocurrency enjoyed approximately $1.8 million worth of stablecoin liquidity. By March 2025, that figure had dropped to just $5,500.

As a project, you’re now competing for attention with over 40 million other tokens—up from just 5 million three years ago. So how do you retain token holders? You can try building a community where members say "GM" on Discord and run some airdrop campaigns.

But then what? Once they get their tokens, they move on to the next Discord server to say “GM” again.

Community members won’t stay without reason—you need to give them one. In my view, that reason is either a high-quality product generating real cash flows or making your project’s metrics look good.

Russ Hanneman Syndrome

In the TV show *Silicon Valley*, Russ Hanneman boasted about becoming a billionaire by “putting radio on the internet.” In crypto, everyone wants to be Russ—chasing overnight riches while ignoring the “boring” but essential aspects like business fundamentals, moats, and sustainable revenue.

Joel’s recent articles, Death to Stagnation and Make Revenue Great Again, emphasize that crypto projects urgently need to focus on sustainable value creation. Just as Russ dismisses Richard Hendricks’ concerns about building a sustainable revenue model, many crypto projects rely on speculative narratives and investor enthusiasm. Now, it's clear this strategy is unsustainable.

But unlike Russ, founders can't succeed just by shouting “Tres Comas.” Most projects require sustainable income—and to achieve that, we must first understand how today’s revenue-generating projects actually do it.

https://youtu.be/BzAdXyPYKQo

The Zero-Sum Game of Attention

In traditional markets, regulators maintain liquidity by imposing high barriers to public listing. Out of 359 million companies globally, only about 55,000 are publicly traded—just 0.01%. This concentrates capital within a limited pool. But it also reduces early-stage investment opportunities with high return potential.

Fragmented attention and liquidity are the price of allowing every token to be easily tradable. I'm not judging which system is better—just highlighting the differences between these two worlds.

The real question is: how do you stand out in an ocean of seemingly infinite tokens? One way is to demonstrate genuine demand for your project and involve token holders in its growth. Don’t get me wrong—not every project needs to obsess over maximizing revenue and profit.

Revenue isn’t the goal; it’s a means to long-term viability.

For example, an L1 hosting enough applications only needs to earn enough fees to offset token inflation. Ethereum validators earn around 3.5%, meaning the annual token supply increases by 3.5%. Any ETH staker sees their holdings diluted. But if Ethereum burns an equivalent amount through fee-burning mechanisms, regular ETH holders avoid dilution.

Ethereum doesn’t need to be profitable—it already has a thriving ecosystem. As long as validators earn enough to keep nodes running, additional revenue isn't critical. But for projects with ~20% circulating supply, the situation is different. These projects resemble traditional companies and may need time before enough volunteers exist to sustain operations.

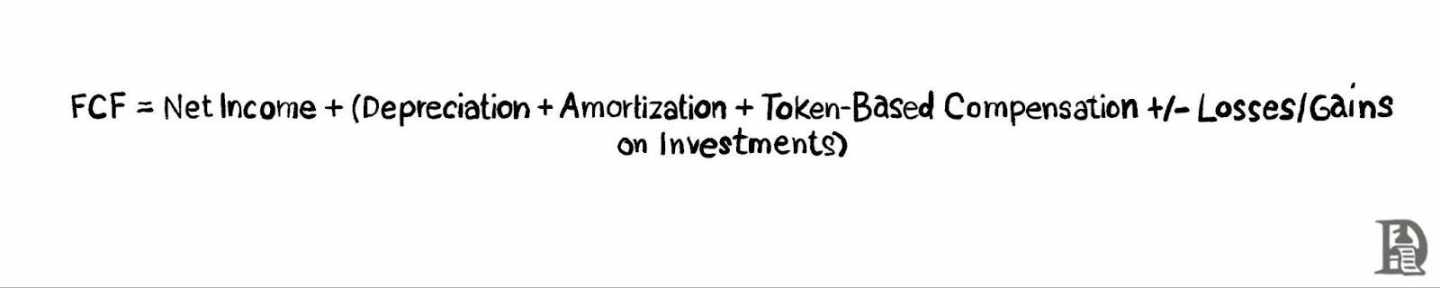

Founders must confront the reality Russ Hanneman ignored: generating real, consistent income is crucial. To clarify, when I refer to “revenue” here, I mean free cash flow (FCF), since underlying financial data is often unavailable for most crypto projects.

Understanding how to allocate FCF—whether to reinvest for growth, share with token holders, and whether via buybacks or dividends—may determine the success or failure of founders aiming to build lasting value.

Looking at equity markets offers helpful guidance. Traditional companies often distribute FCF via dividends and share buybacks. Maturity, industry, profitability, growth potential, market conditions, and shareholder expectations all influence these decisions.

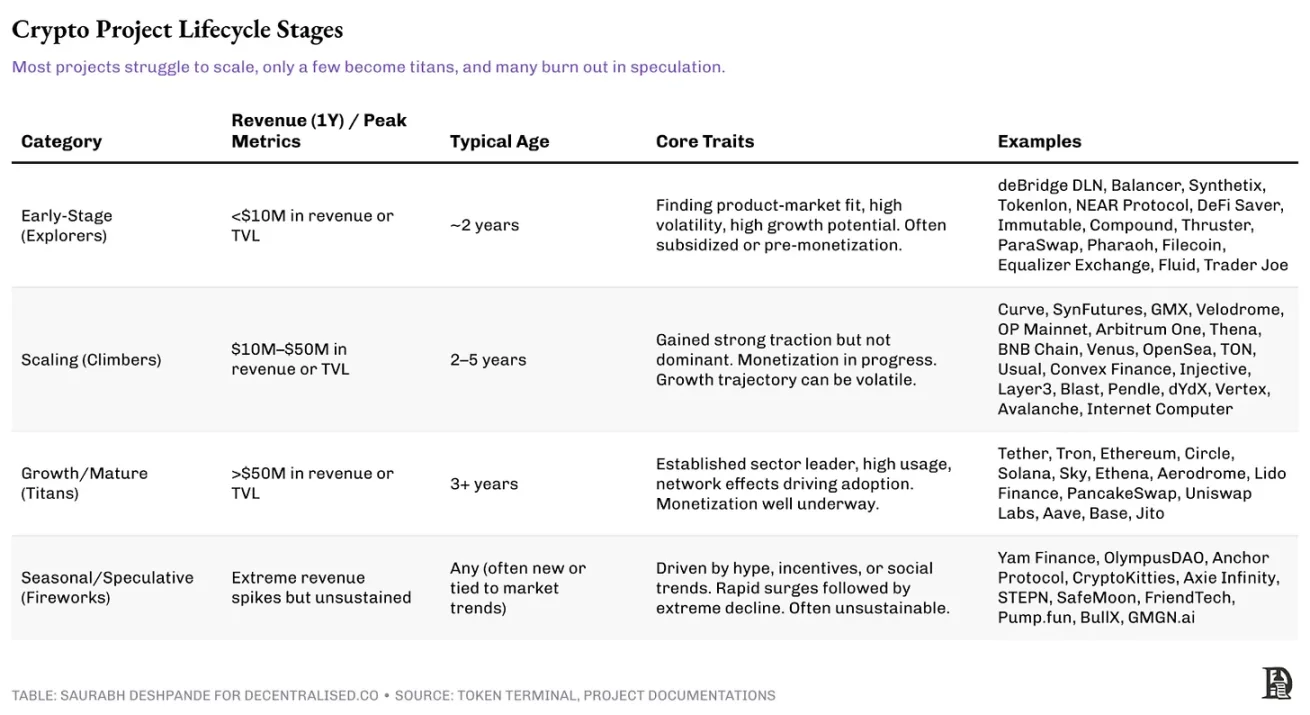

Different crypto projects face distinct opportunities and constraints in value redistribution based on their lifecycle stage. Below, I’ll detail these stages.

Crypto Project Lifecycle

(1) The Explorer Phase

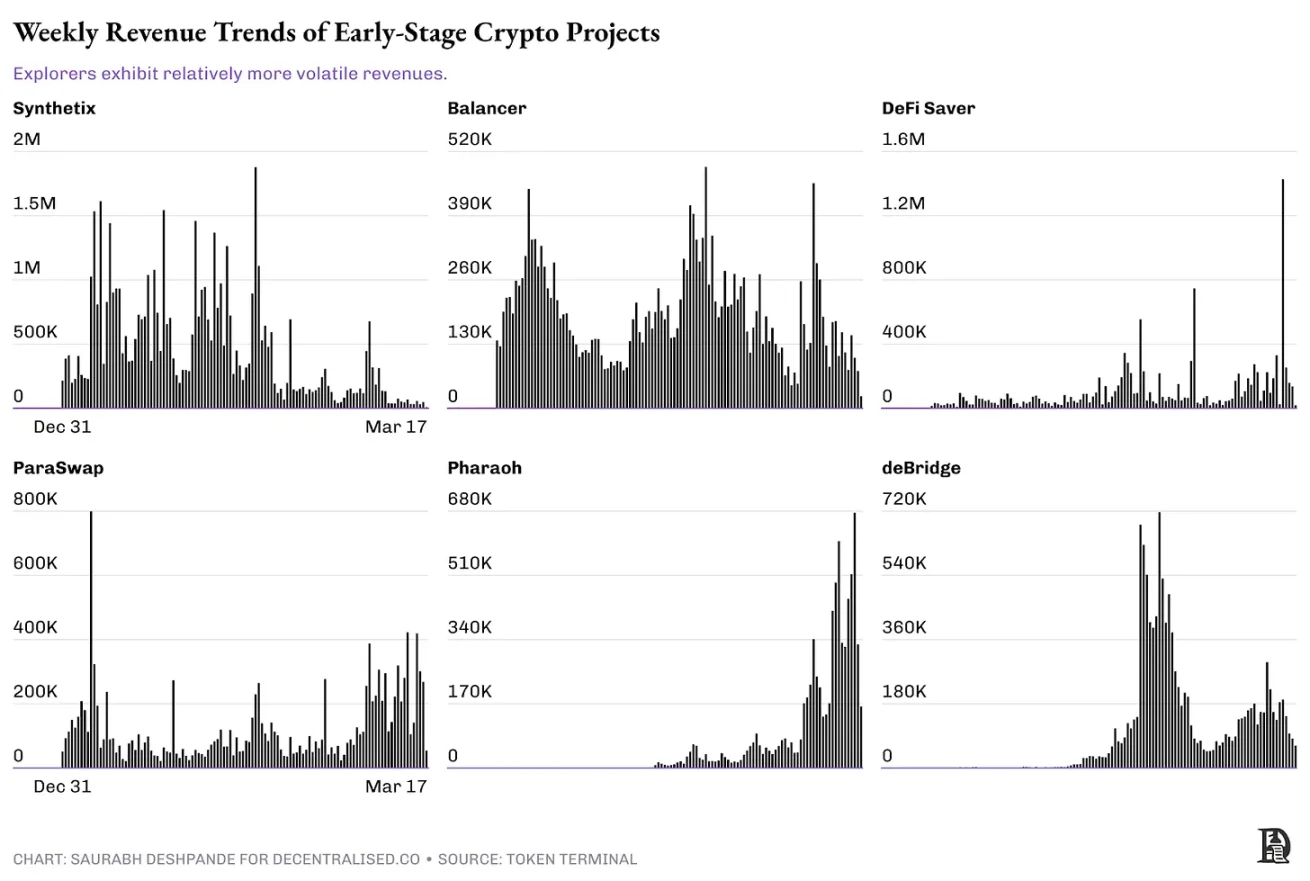

Early-stage crypto projects are typically experimental, focused on user acquisition and refining core products rather than aggressive monetization. Product-market fit remains uncertain. Ideally, these projects prioritize reinvestment for long-term growth over profit-sharing programs.

Governance is usually centralized, with founding teams controlling upgrades and strategy. The ecosystem is nascent, network effects weak, and user retention a major challenge. Many rely on token incentives, venture funding, or grants to bootstrap initial adoption—not organic demand.

While some may achieve early niche success, they still need to prove sustainability. Most crypto startups fall into this category, with only a few progressing beyond.

These projects are still searching for product-market fit. Their revenue patterns reveal struggles with sustained growth. Projects like Synthetix and Balancer show sharp revenue spikes followed by steep declines, indicating periods of speculation rather than steady adoption.

(2) The Climber Phase

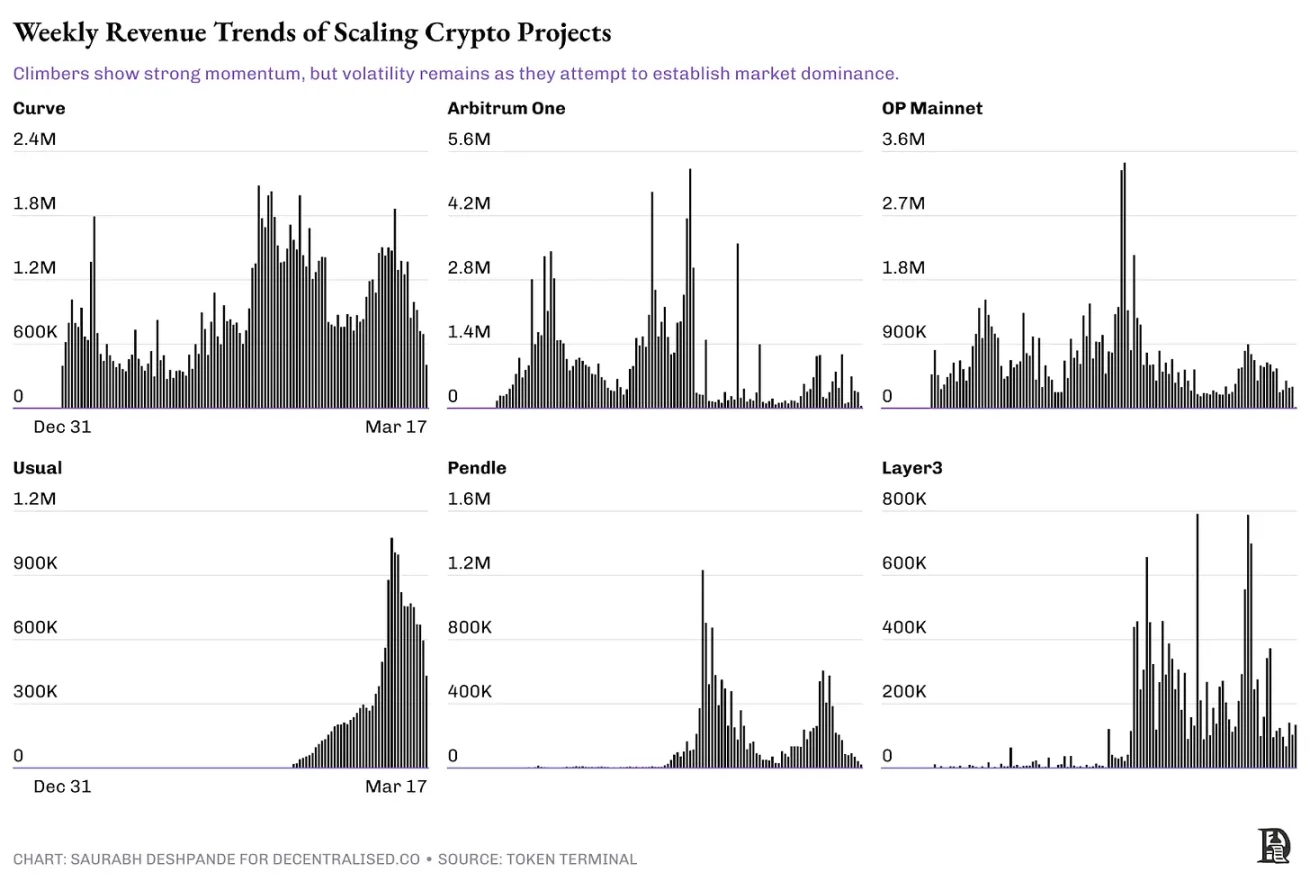

Projects past the early stage but not yet dominant fall into the growth category. These protocols generate meaningful revenue—between $10M and $50M annually. They're still growing, governance is evolving, and reinvestment remains a priority. Some consider yield-sharing mechanisms but must balance distribution with expansion.

This chart tracks weekly revenue for climbing-phase crypto projects. These protocols have gained traction but are still solidifying long-term positions. Unlike explorers, they show clear revenue—but growth trajectories remain unstable.

Protocols like Curve and Arbitrum One exhibit relatively stable revenue streams with visible peaks and troughs, suggesting volatility driven by market cycles and incentives. OP Mainnet shows similar trends—surges during high-demand periods, followed by slowdowns. Meanwhile, Usual shows exponential revenue growth, indicating rapid adoption, though insufficient historical data exists to confirm sustainability. Pendle and Layer3 see sharp activity spikes, signaling high current engagement but revealing challenges in maintaining momentum.

Many L2 scaling solutions (e.g., Optimism, Arbitrum), DeFi platforms (e.g., GMX, Lido), and emerging L1s (e.g., Avalanche, Sui) belong here. According to Token Terminal, only 29 projects currently exceed $10M in annual revenue—though the actual number may be slightly higher. These projects are at a turning point: those strengthening network effects and user retention will advance; others may stagnate or decline.

For climbers, the path forward lies in reducing reliance on incentives, reinforcing network effects, and proving revenue growth can persist—not reverse abruptly.

(3) The Giant Phase

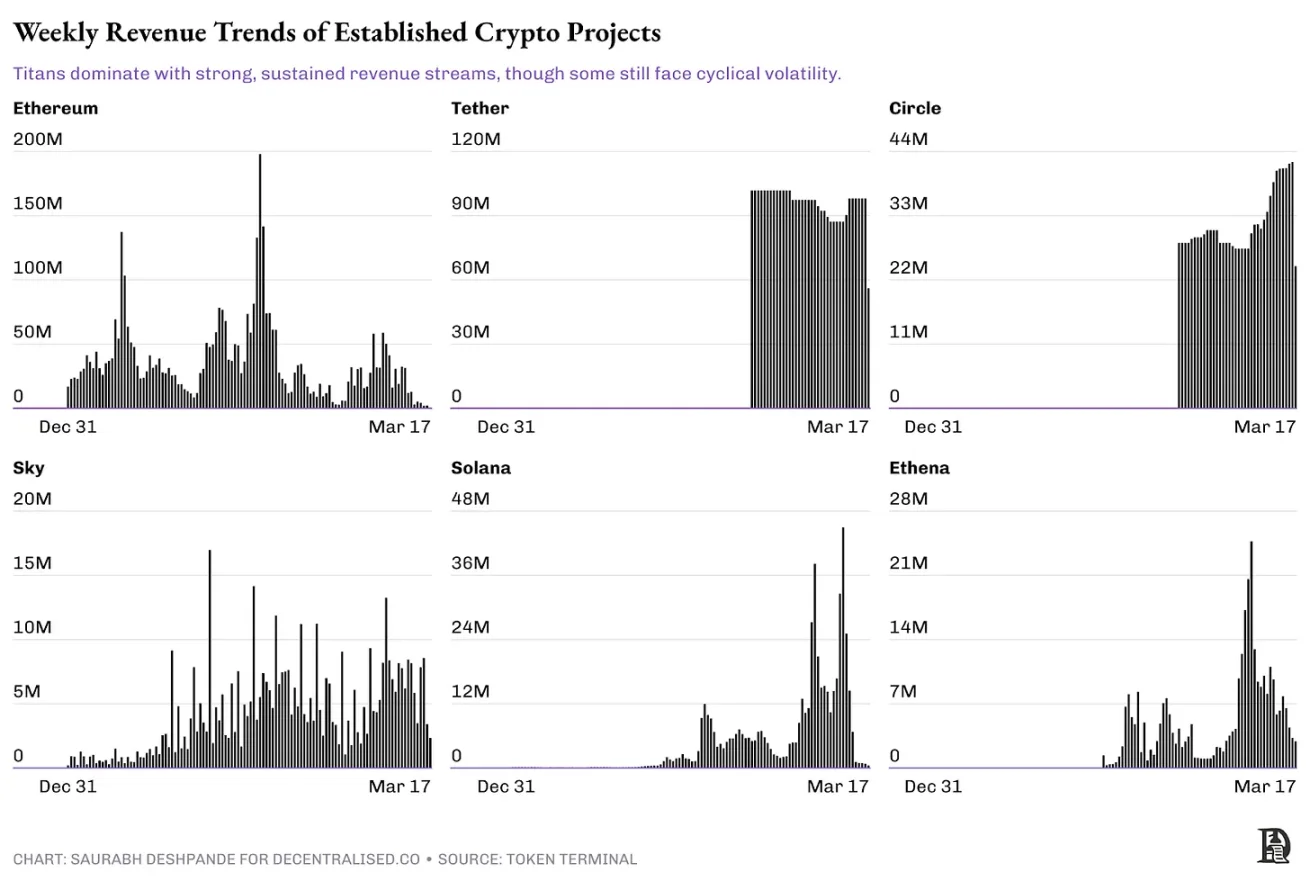

Mature protocols like Uniswap, Aave, and Hyperliquid sit at the intersection of growth and maturity. They’ve achieved product-market fit and generate substantial cash flows. These projects can implement structured buybacks or dividends, bolstering holder trust and ensuring long-term sustainability. Governance is more decentralized, with communities actively involved in upgrades and treasury decisions.

Network effects create competitive moats, making them hard to displace. Only dozens of projects reach this revenue level—indicating how few truly mature. Unlike earlier-stage projects, these don’t rely on inflationary token incentives but earn sustainable income via trading fees, lending interest, or staking commissions. Their resilience across market cycles further separates them from speculative ventures.

Unlike early or growth-stage projects, these protocols exhibit strong network effects, solid user bases, and deeper market roots.

Ethereum leads in decentralized revenue generation, showing cyclical peaks aligned with high network activity. Stablecoin giants Tether and Circle display different patterns—more stable, structured revenue streams rather than wild swings. Solana and Ethena generate significant revenue but still show clear growth-and-retreat cycles, reflecting fluctuating adoption. Meanwhile, Sky’s revenue is erratic, suggesting volatile demand rather than sustained dominance.

Even giants aren’t immune to volatility. The difference lies in their ability to maintain revenue during downturns.

(4) The Seasonal Projects

Some projects experience rapid but unsustainable growth due to hype, incentives, or social trends. Platforms like FriendTech and memecoins may generate massive revenue during peak cycles but struggle to retain users long-term. Premature yield-sharing plans can amplify volatility—as incentives dry up, speculative capital flees quickly. Governance is often weak or centralized, ecosystems thin, and dApp adoption limited or lacking long-term utility.

Though these projects may temporarily command high valuations, they’re vulnerable to collapse when sentiment shifts, leaving investors disappointed. Many speculative platforms rely on unsustainable token emissions, fake volume, or inflated yields to manufacture artificial demand. While a few escape this phase, most fail to build durable business models—making them inherently high-risk investments.

Profit-Sharing Models in Public Companies

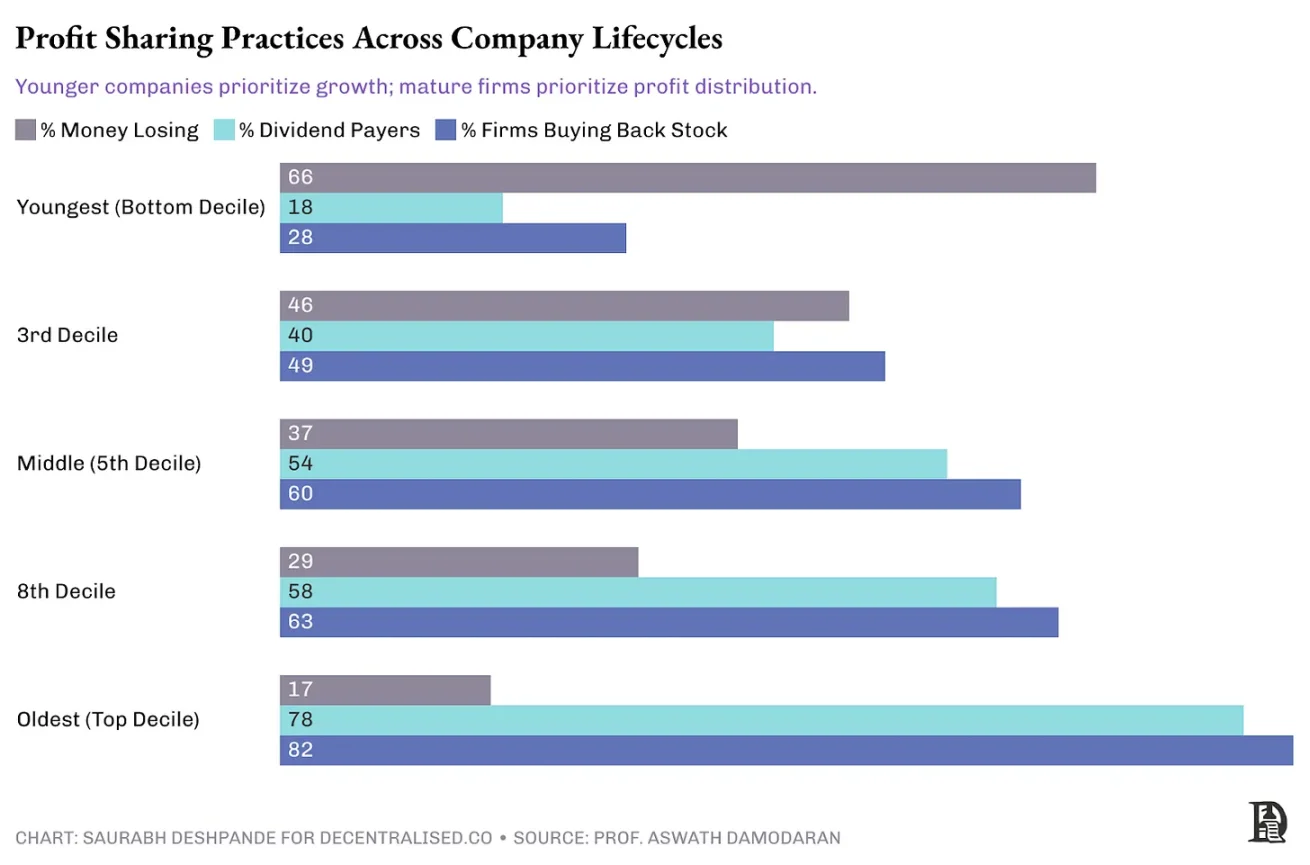

Observing how public companies manage surplus profits offers valuable lessons.

This chart shows how profit-sharing behavior evolves as companies mature. Young firms face high financial losses (66%), so they tend to retain earnings for reinvestment rather than pay dividends (18%) or conduct buybacks (28%). As companies mature, profitability stabilizes, and dividend payouts and buybacks increase. Mature firms frequently distribute profits—dividends (78%) and buybacks (82%) become common.

These trends mirror the crypto project lifecycle. Like young traditional companies, early crypto “explorers” typically prioritize reinvestment to find product-market fit. Conversely, mature crypto “giants,” like established traditional firms, can afford to distribute income via token buybacks or dividends, boosting investor confidence and long-term viability.

The relationship between company age and profit-sharing naturally extends to sector-specific practices. While young firms generally favor reinvestment, mature ones adapt strategies to their industries. Capital-stable sectors prefer predictable dividends, while innovative, volatile industries favor the flexibility of buybacks. Understanding these nuances helps crypto founders tailor income distribution strategies to align lifecycle stage, industry characteristics, and investor expectations.

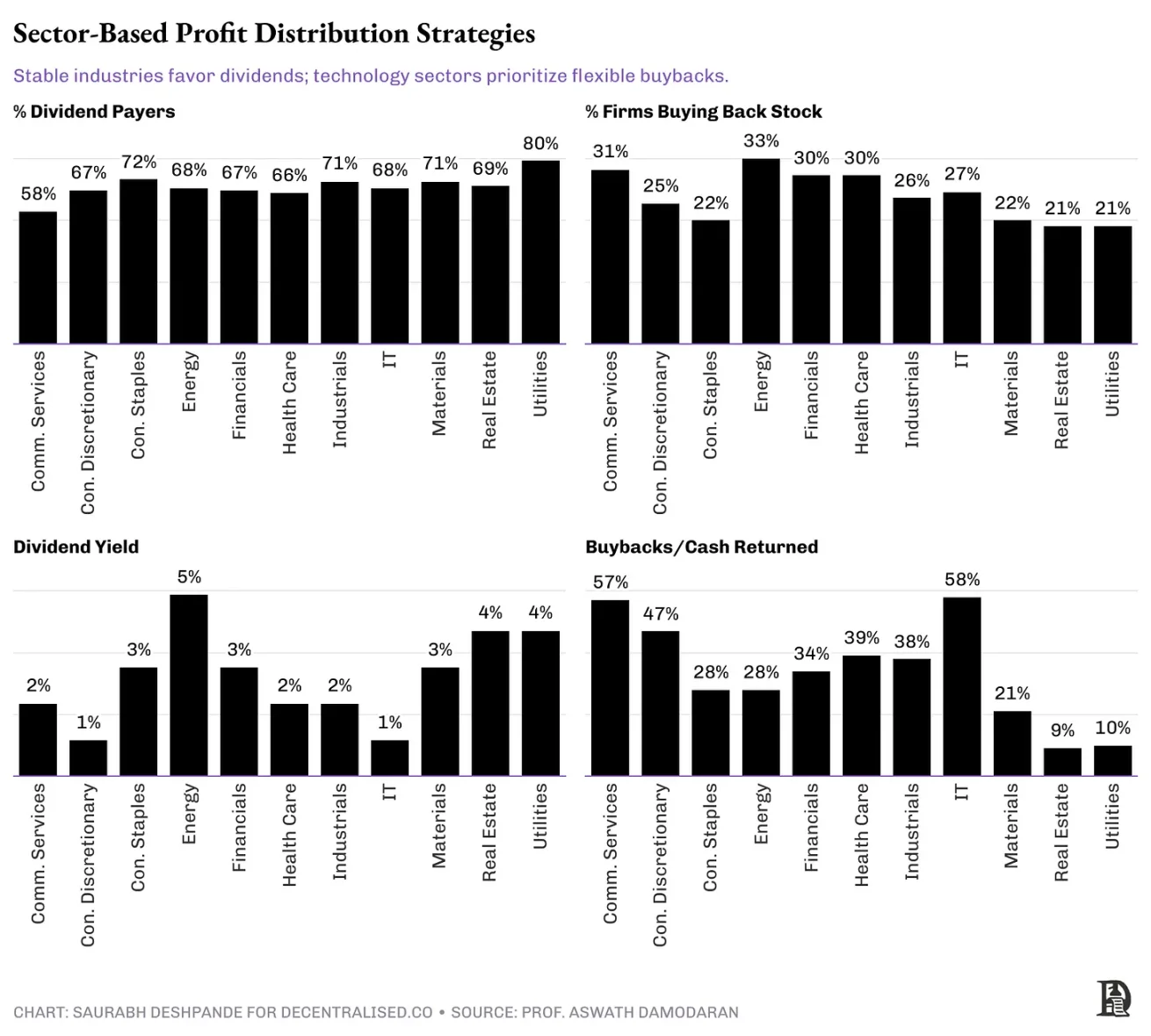

The following chart highlights distinct profit-distribution strategies across industries. Traditional, stable sectors like utilities (80% pay dividends, 21% conduct buybacks) and consumer staples (72% pay dividends, 22% conduct buybacks)—with predictable cash flows—strongly favor dividends. In contrast, tech-focused sectors like information technology (27% conduct buybacks, highest cash return via buybacks at 58%) prefer buybacks for flexibility amid volatile revenues.

These insights directly apply to crypto. Protocols with stable, predictable revenue—like stablecoin issuers or mature DeFi platforms—may best suit ongoing, dividend-like payments. Conversely, high-growth, innovation-driven crypto projects—especially in DeFi and infrastructure—can adopt flexible token buyback models, mirroring traditional tech strategies to adapt to volatile, fast-changing conditions.

Dividends vs. Buybacks

Both methods have pros and cons, but recently, buybacks have gained preference over dividends. Buybacks offer more flexibility; dividends are sticky. Once you announce a X% dividend, investors expect it every quarter. Buybacks provide strategic wiggle room—not just in how much profit to return, but when—allowing adaptation to market cycles without being locked into rigid dividend schedules. Buybacks don’t set fixed expectations and are seen as one-off actions.

But buybacks are wealth transfers—a zero-sum game. Dividends create value for all shareholders. So both have a place.

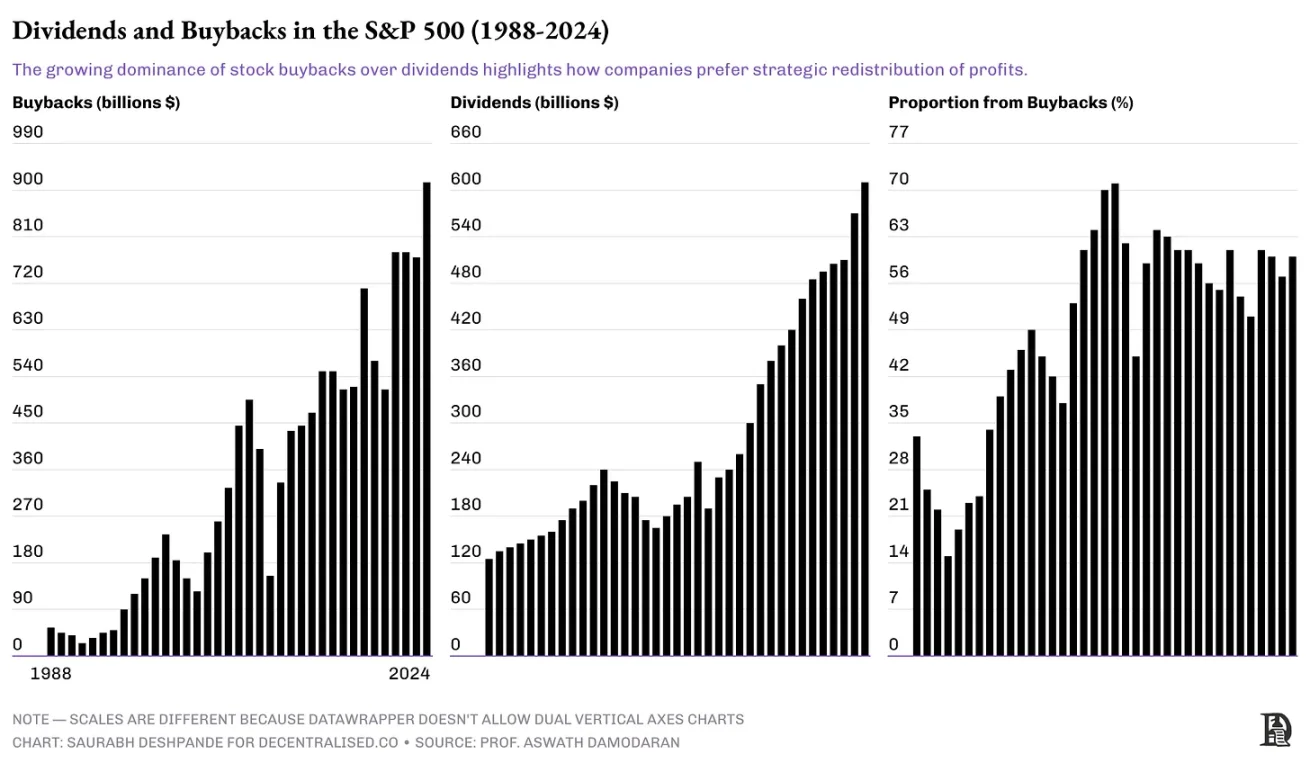

Recent trends show buybacks gaining popularity for the reasons above.

In the early 1990s, only about 20% of profits were distributed via buybacks. By 2024, that figure reached ~60%. In dollar terms, buybacks surpassed dividends in 1999 and have remained ahead ever since.

From a governance perspective, buybacks require careful valuation assessment to avoid unintentionally transferring wealth from long-term holders to those selling at high valuations. When a company buys back shares, it ideally believes the stock is undervalued. Sellers believe it’s overvalued. Both can’t be right. Generally, companies are assumed to know their own plans better—so sellers during buybacks might miss out on future gains.

According to a Harvard Law School paper, current disclosure practices often lack timeliness, making it hard for shareholders to assess buyback progress or maintain ownership stakes. Also, when executive compensation ties to metrics like EPS, buybacks can distort incentives—pushing leaders to prioritize short-term stock performance over long-term growth.

Despite these governance challenges, buybacks remain attractive—especially for U.S. tech firms—due to operational flexibility, autonomy in investment decisions, and lower future expectations compared to dividends.

Revenue Generation & Distribution in Crypto

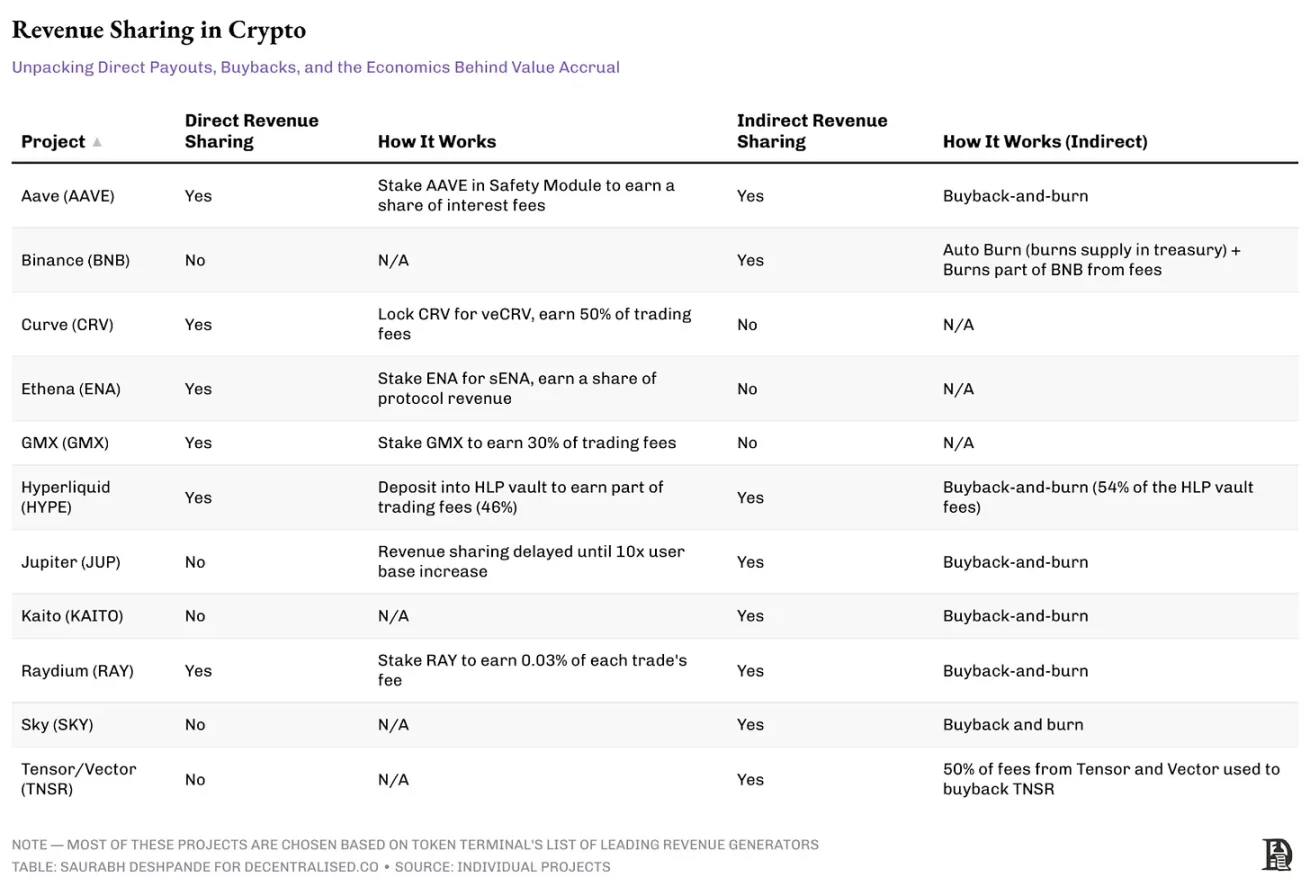

According to Token Terminal, 27 crypto projects generate $1M+ in monthly revenue. This isn’t exhaustive—it misses platforms like PumpFun and BullX—but close enough. I examined 10 of them to see how they handle revenue. The key takeaway: most crypto projects shouldn’t even consider distributing income or profits to token holders. On this front, I admire Jupiter. At launch, they explicitly stated they had no intention of sharing direct returns (like dividends). Only after user numbers grew tenfold did Jupiter introduce a buyback-like mechanism to return value to token holders.

Yield Sharing in Crypto Projects

Crypto projects must rethink how they share value with token holders—drawing inspiration from traditional enterprises while adopting novel approaches to avoid regulatory scrutiny. Unlike stocks, tokens enable innovative integration directly into product ecosystems. Instead of simply distributing profits, projects can actively incentivize key ecosystem activities.

For example, Aave rewarded token stakers providing critical liquidity before launching buybacks. Similarly, Hyperliquid strategically shares 46% of revenue with liquidity providers—analogous to traditional customer loyalty models in mature businesses.

Beyond token-integrated strategies, some projects use more direct yield-sharing methods reminiscent of public equity practices. However, even direct models require caution to avoid being classified as securities—balancing reward distribution with regulatory compliance. Projects based outside the U.S., like Hyperliquid, often have more freedom in implementing such models.

Jupiter exemplifies creative value sharing. Instead of traditional buybacks, they use a third-party entity, Litterbox Trust, coded to receive JUP tokens equal to half of Jupiter’s protocol revenue. As of March 26, it had accumulated ~18 million JUP, worth ~$9.7M. This mechanism directly ties token holders to the project’s success while sidestepping regulatory issues tied to conventional buybacks.

Remember: Jupiter only pursued this path after accumulating a robust stablecoin treasury sufficient to fund operations for years.

The rationale for allocating 50% of revenue to this accumulation plan is simple. Jupiter follows a guiding principle of balanced ownership between team and community, fostering alignment and shared incentives. This approach also encourages token holders to actively promote the protocol—directly linking their financial interests to product growth and success.

Aave recently launched token buybacks after a structured governance process. With a healthy treasury exceeding $95M (excluding its own token holdings), Aave initiated the program in early 2025 following detailed governance proposals. Named “Buy and Distribute,” the plan allocates $1M weekly for buybacks—preceded by extensive community discussion on tokenomics, treasury management, and price stability. Aave’s treasury growth and financial strength allow this initiative without compromising operations.

Hyperliquid uses 54% of revenue to buy back HYPE tokens, with the remaining 46% incentivizing exchange liquidity. Buybacks are executed through the Hyperliquid Aid Fund. Since launch, the fund has purchased over 18 million HYPE tokens—worth over $250M as of March 26.

Hyperliquid stands out: its team avoided VC funding, likely self-funded development, and now dedicates 100% of revenue to rewarding liquidity providers or buying back tokens. Other teams may find this hard to replicate. But both Jupiter and Aave illustrate a key point: strong financial health enables buybacks without harming core operations—reflecting disciplined financial management and strategic foresight. This is a model every project can emulate. Build sufficient reserves before launching buybacks or dividends.

Tokens as a Product

Kyle made a great point: crypto projects need Investor Relations (IR) roles. It's ironic that an industry built on transparency performs poorly on operational transparency. Most external communication happens via sporadic Discord announcements or Twitter threads, financial metrics are selectively shared, and expense disclosures are largely opaque.

When token prices keep falling, users quickly lose interest in the underlying product—unless it has a strong moat. This creates a vicious cycle: falling prices reduce interest, further depressing prices. Projects need compelling reasons for holders to stay and non-holders to buy.

Clear, consistent communication about development progress and fund usage can itself become a competitive advantage in today’s market.

In traditional markets, IR departments bridge companies and investors through quarterly earnings reports, analyst calls, and performance guidance. The crypto industry can adopt this model while leveraging its unique technological advantages. Regular quarterly reporting on revenue, operating costs, and development milestones—combined with on-chain verification of treasury flows and buyback activity—would greatly enhance stakeholder confidence.

The biggest transparency gap lies in spending. Publicly disclosing team salaries, expense details, and grant allocations preempts questions that usually arise only after project failures: “Where did the ICO money go?” and “How much does the founder pay themselves?”

Strong IR practices offer strategic benefits beyond transparency. They reduce volatility by minimizing information asymmetry, broaden the investor base by easing institutional entry, cultivate informed long-term holders who stay through market cycles, and build community trust that helps projects survive crises.

Forward-thinking projects like Kaito, Uniswap Labs, and Sky (formerly MakerDAO) are already moving in this direction, publishing regular transparent reports. As Joel noted in his article, the crypto industry must break free from speculative cycles. By adopting professional IR practices, projects can shed their “casino” reputation and become Kyle’s envisioned “compounding creators”—assets capable of generating sustainable value over time.

In a market where capital grows increasingly discerning, transparent communication will become a necessity for survival.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News