Pentagon Pizza, Polymarket Money

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Pentagon Pizza, Polymarket Money

The first to know that the U.S. military was about to take action might have been the pizza shop near the Pentagon.

Written by: Wawa, TechFlow

During the Cold War, Soviet agents had a routine task:

Count how many lights were on at the Pentagon at night and how many cars were in the parking lot.

At the same time, they monitored another indicator: how many pizza deliveries were sent in late at night.

The logic was simple. If war was imminent, people would work overtime, and working overtime meant needing food. The only thing that could be delivered to the Pentagon at 2 a.m. was pizza.

In 1990, Frank Meeks, a Domino's franchisee in Washington, told a story in an interview with the Los Angeles Times.

On the night of August 1, his store delivered 21 pizzas to the CIA.

This was a single-night record.

The next day, Iraq invaded Kuwait, and the Gulf War began.

Meeks recalled that this wasn't the first time. The night before the 1983 invasion of Grenada, his store's late-night orders jumped from the usual 40-50 to nearly 100. Before the 1989 invasion of Panama, orders at three pizza shops in Washington tripled.

Wolf Blitzer, then a Pentagon reporter for CNN, heard this story and said a line that would be repeatedly quoted later:

"A reporter's bottom line: always watch the pizza."

This pattern later got a name: the "Pentagon Pizza Index."

During the Clinton impeachment proceedings in 1998, the White House ordered $2,600 worth of pizza from Domino's over three days. In December of the same year, when the U.S. military bombed Iraq, pizza orders on Capitol Hill were 32% higher than usual.

In 2004, Frank Meeks passed away at the age of 48.

But the observation he left behind lived on.

In August 2024, someone registered a Twitter account called @PenPizzaReport.

This account does one thing: uses Google Maps' "Popular Times" feature to monitor in real-time the customer traffic at several pizza shops near the Pentagon. District Pizza Palace, Domino's, We the Pizza, Papa John's—when each shop is busier than usual and by how much can be seen.

The account quickly gained 80,000 followers.

Someone went further and created a website called pizzint.watch, automating the monitoring. The homepage has an index called "Pizza DEFCON," ranging from 1 to 5, with 5 being peacetime and 1 meaning war is imminent. It updates every 10 minutes.

What Soviet agents during the Cold War had to stake out and count can now be seen by anyone opening a webpage.

At 7 p.m. on June 12, 2025, @PenPizzaReport tweeted: "Huge spikes in traffic at almost all pizza places near the Pentagon."

The accompanying image was a Google Maps screenshot showing District Pizza Palace's real-time traffic significantly higher than usual.

At the same time, customer traffic at a gay bar near the Pentagon was unusually low. This was also an old indicator: if Pentagon staff are all working overtime, nearby bars become quiet.

A few hours later, Israel bombed Iran.

At 10:38 p.m. on June 22, @PenPizzaReport issued another alert: abnormal traffic at Papa John's.

One hour later, Trump announced a U.S. military airstrike on Iranian nuclear facilities.

Alex Selby-Boothroyd, head of data journalism at The Economist, wrote on LinkedIn: "The pizza index has been a surprisingly reliable predictor of major global events since the 1980s."

Does the Pentagon know about this?

Yes.

Last October, when Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth was asked about the pizza tracking account in a Fox News interview, he said: "I know that account. I've thought about ordering a bunch of pizzas on random nights to mess with them."

A Pentagon spokesperson also responded, saying there's plenty of food inside the building—pizza, sushi, sandwiches, donuts—so delivery isn't needed.

But orders still spike.

There are rumors that after the 1991 Gulf War, the Pentagon started spreading orders across multiple restaurants to avoid abnormal spikes at any single pizza shop.

But Google Maps doesn't care which shop you order from. It monitors traffic for the entire area.

In the early hours of January 3, U.S. forces raided Venezuela and captured Maduro.

Afterwards, someone checked the pizzint.watch records. Hours before the operation, the Pizza DEFCON rose to level 4, with traffic nearly double the usual.

@PenPizzaReport also issued an alert.

But this time, the story wasn't just about pizza.

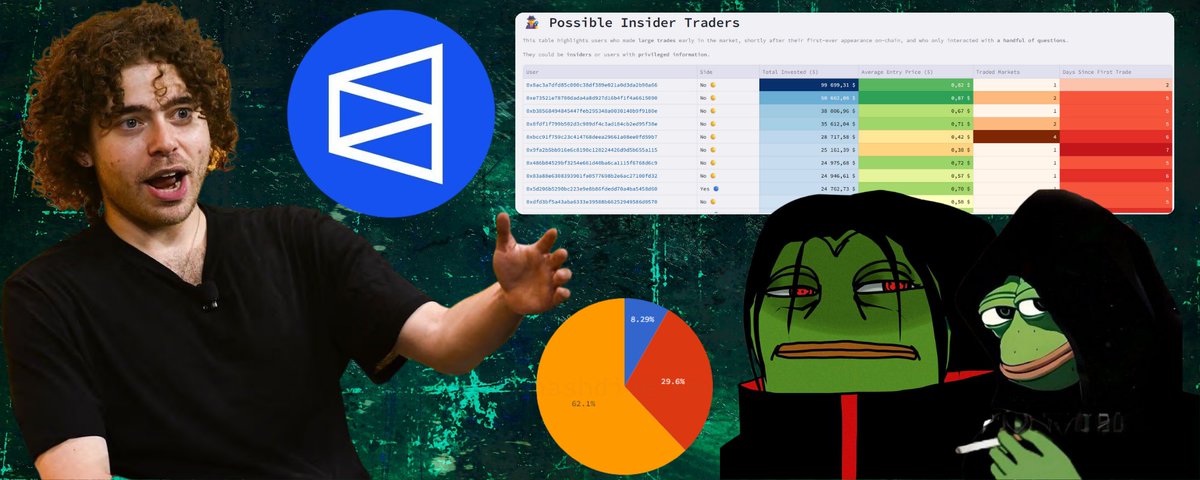

On-chain analyst lookonchain discovered that three wallets on Polymarket heavily bet on "Maduro stepping down" hours before the operation.

These three wallets shared several characteristics:

All were created just days prior. They only bet on Venezuela-related markets. They had no other transaction history.

One wallet, registered on December 27, invested $34,000 when the odds for "Maduro stepping down before January 31" were only 6%. Another invested $5,800, and the third invested $25,000.

By the time Trump posted on Truth Social at 4:21 a.m., the total profit for the three wallets was:

$630,000.

According to a report by The New Republic, the U.S. military discussed this operation on Christmas Day. On December 27, one of the wallets was registered.

Coincidence?

The Wall Street Journal calculated that markets related to Maduro on Polymarket attracted a total of $56.6 million in bets. Of that, $40 million was bet on him stepping down by the end of November or December, and all lost.

These three wallets bet on before January 31.

But who are these three wallets?

No one knows. On-chain addresses are public, but the people behind them are not. Polymarket operates on the Polygon chain, with servers located outside the U.S.

U.S. Congressman Ritchie Torres said he would introduce a bill called the "Public Integrity Financial Prediction Markets Act of 2026," prohibiting federal officials and political insiders from betting on prediction markets.

But even if it was someone from the White House placing the bets, you couldn't trace it.

Some call it insider trading.

But others say maybe they just looked at the pizza index.

Putting the timeline together:

In the 1980s, Soviet agents staked out and counted pizza deliveries. This was the specialized skill of intelligence agencies.

In the 1990s, Frank Meeks told this pattern to journalists. It became an urban legend.

In 2024, someone used Google Maps to turn it into a public website. Anyone could see it.

In 2026, someone looked at this public information and made $630,000 on a prediction market.

Incidentally, The New York Times and The Washington Post also knew about the operation before it began. But both newspapers chose to hold the story. The reason given was to protect U.S. military safety, in line with "longstanding American journalistic tradition."

While traditional media was still debating whether to publish, the information had already run ahead.

Today, the old order of information is loosening. "Who knows first" is being redefined.

In the new order, information is scattered across various public data sets, waiting to be discovered, combined, and priced.

When the Pentagon's appetite becomes an oracle for all of humanity, we realize:

The fog of war still exists, but it no longer smells of gunpowder; it might smell of pizza.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News