Will Bitcoin be broken by quantum computers by 2030?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Will Bitcoin be broken by quantum computers by 2030?

Companies like Google and AWS have already begun adopting post-quantum cryptography, but Bitcoin and Ethereum are still in the early discussion stages.

Author: Tiger Research

Translation: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

Advancements in quantum computing are introducing new security risks to blockchain networks. This section aims to explore technologies designed to counter quantum threats and examine how Bitcoin and Ethereum are preparing for this shift.

Key Takeaways

-

The Q-Day scenario—where quantum computers can break blockchain cryptography—is estimated to arrive within five to seven years. BlackRock also highlighted this risk in its Bitcoin ETF filing.

-

Post-quantum cryptography provides protection against quantum attacks across three security layers: communication encryption, transaction signatures, and data integrity.

-

Companies like Google and AWS have already started adopting post-quantum cryptography, while Bitcoin and Ethereum remain in early discussion stages.

A New Technology Introduces Unfamiliar Problems

If a quantum computer could crack a Bitcoin wallet in minutes, could blockchain security still hold?

The foundation of blockchain security lies in private key protection. To steal someone's Bitcoin, an attacker must obtain the private key—a task that is practically impossible under current computing models. Only the public key is visible on-chain, and even with supercomputers, deriving the private key from it would take hundreds of years.

Quantum computers alter this risk landscape. Classical computers process 0s or 1s sequentially, whereas quantum systems can handle both states simultaneously. This capability makes it theoretically possible to derive private keys from public ones.

Experts estimate that quantum computers capable of breaking modern cryptography may emerge around 2030. This anticipated moment is known as Q-Day, indicating five to seven years until practical attacks become feasible.

Source: SEC

Regulators and major institutions have recognized this risk. In 2024, the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology introduced post-quantum cryptography standards. BlackRock also noted in its Bitcoin ETF application that advances in quantum computing could threaten Bitcoin’s security.

Quantum computing is no longer a distant theoretical issue. It has become a technical challenge requiring practical preparation rather than reliance on assumptions.

Quantum Computing Challenges Blockchain Security

To understand how blockchain transactions work, consider a simple example: Ekko sends 1 BTC to Ryan.

When Ekko creates a transaction stating "I send my 1 BTC to Ryan," he must attach a unique signature. This signature can only be generated using his private key.

Ryan and other nodes in the network then use Ekko’s public key to verify the signature’s validity. The public key acts like a tool that verifies but cannot recreate the signature. As long as Ekko keeps his private key secret, no one can forge his signature.

This forms the basis of blockchain transaction security.

A private key can generate a public key, but a public key cannot reveal the private key. This is achieved through the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA), which relies on elliptic curve cryptography. ECDSA depends on mathematical asymmetry—easy computation in one direction, computationally infeasible in reverse.

With the rise of quantum computing, this barrier is weakening. The key element is the qubit.

Classical computers process 0s or 1s sequentially. Qubits can represent both states at once, enabling massive parallel computation. With enough qubits, a quantum computer can perform in seconds what would take classical computers decades.

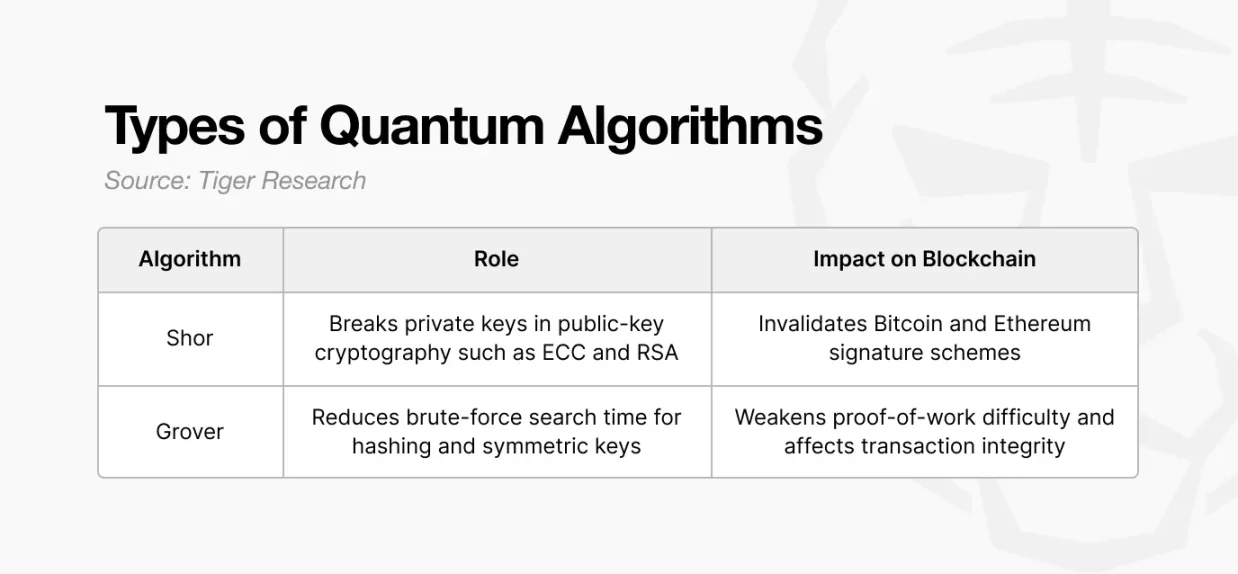

Two quantum algorithms pose direct risks to blockchain security.

Shor’s algorithm offers a path to derive private keys from public keys, undermining public-key cryptography. Grover’s algorithm reduces the effective strength of hash functions by accelerating brute-force searches.

Shor’s Algorithm: Direct Asset Theft

Most internet security today relies on two public-key cryptosystems: RSA and ECC.

These systems resist external attacks by leveraging hard mathematical problems such as integer factorization and discrete logarithms. Blockchains use the same principle via ECDSA based on ECC.

With current computing power, breaking these systems would take decades, making them practically secure.

Shor’s algorithm changes this. A quantum computer running Shor’s algorithm can rapidly perform large integer factorizations and discrete logarithm calculations—capabilities that can break RSA and ECC.

Using Shor’s algorithm, a quantum attacker could derive a private key from a public key and freely transfer assets from the corresponding address. Any address that has ever sent a transaction is at risk because its public key becomes visible on-chain. This could result in millions of addresses being simultaneously vulnerable.

Grover’s Algorithm: Transaction Interception

Blockchain security also relies on symmetric-key encryption (e.g., AES) and hash functions (e.g., SHA-256).

AES encrypts wallet files and transaction data, requiring all possible combinations to be tried to find the correct key. SHA-256 supports difficulty adjustment in proof-of-work; miners repeatedly search for hash values meeting specified criteria.

These systems assume that when a transaction waits in the mempool, other users lack sufficient time to analyze or forge it before it is included in a block.

Grover’s algorithm weakens this assumption. It uses quantum superposition to accelerate search processes, reducing the effective security level of AES and SHA-256. A quantum attacker could analyze transactions in real-time within the mempool and generate a forged version using the same inputs (UTXOs) but redirecting outputs to different addresses.

This leads to the risk of transactions being intercepted by attackers equipped with quantum computers, resulting in funds being transferred to unintended destinations. Withdrawals from exchanges and regular transfers could become common targets for such interception.

Post-Quantum Cryptography

How can blockchain security be maintained in the era of quantum computing?

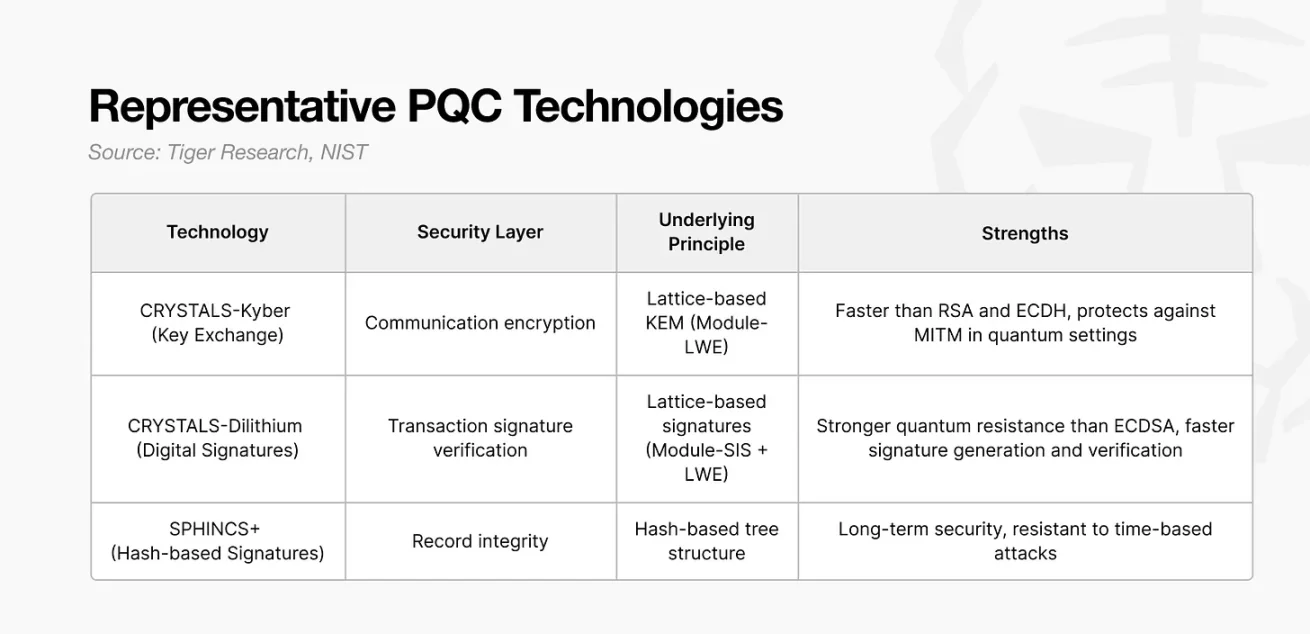

Future blockchain systems need cryptographic algorithms that remain secure even under quantum attacks. These are known as post-quantum cryptography (PQC) techniques.

The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology has proposed three main PQC standards, which both Bitcoin and Ethereum communities are discussing as a foundation for long-term security.

Kyber: Securing Node-to-Node Communication

Kyber is an algorithm designed to allow two parties on a network to securely exchange symmetric keys.

Traditional methods supporting internet infrastructure—such as RSA and ECDH—are vulnerable to Shor’s algorithm and pose exposure risks in a quantum environment. Kyber addresses this by using a lattice-based mathematical problem called Module-LWE, believed to be resistant even to quantum attacks. This structure prevents data from being intercepted or decrypted during transmission.

Kyber secures all communication paths: HTTPS connections, exchange APIs, and wallet-to-node messaging. Within blockchain networks, nodes can also use Kyber when sharing transaction data, preventing third-party monitoring or information extraction.

In practice, Kyber rebuilds the security of the network transport layer for the quantum computing era.

Dilithium: Validating Transaction Signatures

Dilithium is a digital signature algorithm used to verify that transactions were created by the legitimate holder of a private key.

Blockchain ownership relies on the ECDSA model of “signing with a private key, verifying with a public key.” The problem is that ECDSA is vulnerable to Shor’s algorithm. With access to the public key, a quantum attacker could derive the corresponding private key, enabling signature forgery and asset theft.

Dilithium avoids this risk by using a lattice-based structure combining Module-SIS and LWE. Even if an attacker analyzes the public key and signature, the private key cannot be inferred, and the design remains secure against quantum attacks. Implementing Dilithium prevents signature forgery, private key extraction, and mass asset theft.

It protects both asset ownership and the authenticity of every transaction.

SPHINCS+: Preserving Long-Term Records

SPHINCS+ uses a multi-layered hash tree structure. Each signature is verified through a specific path in the tree, and since individual hash values cannot be reversed to reveal their input, the system remains secure even against quantum attacks.

Once Ekko and Ryan’s transaction is added to a block, the record becomes permanent. This is analogous to a document fingerprint.

SPHINCS+ converts each part of a transaction into hash values, creating a unique pattern. If even a single character changes in the document, its fingerprint changes completely. Similarly, modifying any part of the transaction alters the entire signature.

Even decades later, any attempt to modify Ekko and Ryan’s transaction will be immediately detected. Although SPHINCS+ produces relatively large signatures, it is well-suited for financial data or government records that must remain verifiable over the long term. Quantum computers will struggle to forge or replicate this fingerprint.

In summary, PQC technologies build three layers of protection against quantum attacks in a standard 1 BTC transfer: Kyber for communication encryption, Dilithium for signature verification, and SPHINCS+ for record integrity.

Bitcoin and Ethereum: Different Paths, Same Goal

Bitcoin emphasizes immutability, while Ethereum prioritizes adaptability. These design philosophies were shaped by past events and influence how each network approaches the threat of quantum computing.

Bitcoin: Protecting the Existing Chain Through Minimal Changes

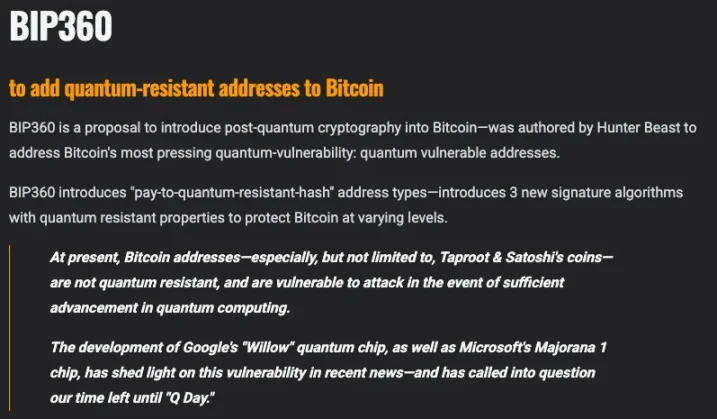

Bitcoin’s emphasis on immutability traces back to the 2010 value overflow incident. A hacker exploited a vulnerability to create 184 billion BTC, and the community invalidated the transaction via a soft fork within five hours. After this emergency action, the principle that “confirmed transactions must never change” became central to Bitcoin’s identity. This immutability preserves trust but makes rapid structural changes difficult.

This philosophy extends to Bitcoin’s approach to quantum security. Developers agree upgrades are necessary, but replacing the entire chain via hard fork is considered too risky for network consensus. Therefore, Bitcoin is exploring gradual transition through a hybrid migration model.

Source: bip360.org

This philosophy extends to Bitcoin’s approach to quantum security. Developers agree upgrades are necessary, but replacing the entire chain via hard fork is considered too risky for network consensus. Therefore, Bitcoin is exploring gradual transition through a hybrid migration model.

If adopted, users could use both traditional ECDSA addresses and new PQC addresses simultaneously. For example, if Ekko holds funds in an old Bitcoin address, he could gradually migrate them to a PQC address as Q-Day approaches. Since the network recognizes both formats, security improves without forcing a disruptive transition.

Challenges remain significant. Hundreds of millions of wallets need migration, and there is no clear solution yet for wallets with lost private keys. Divergent opinions within the community could also increase the risk of chain splits.

Ethereum: Fast Transition Through Flexible Architecture Redesign

Ethereum’s principle of adaptability stems from the 2016 DAO hack. When approximately 3.6 million ETH were stolen, Vitalik Buterin and the Ethereum Foundation executed a hard fork to reverse the theft.

This decision split the community into Ethereum (ETH) and Ethereum Classic (ETC). Since then, adaptability has become a defining feature of Ethereum and a key enabler of rapid change.

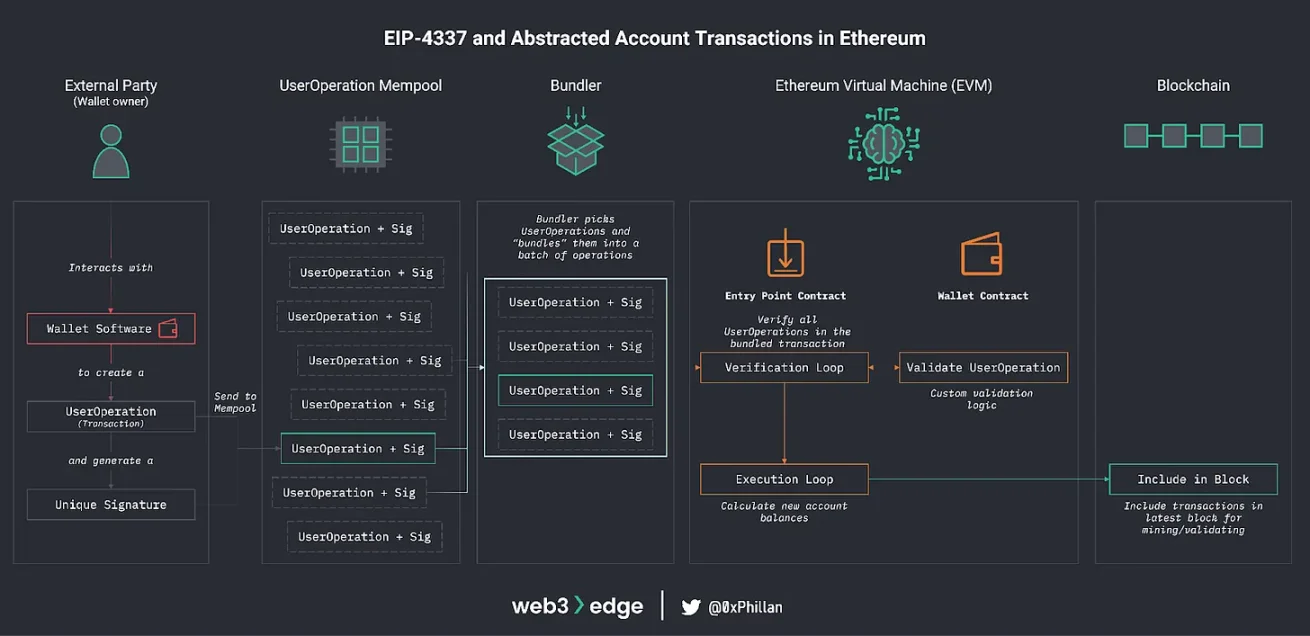

Source: web3edge

Historically, all Ethereum users relied on externally owned accounts, which could only send transactions via the ECDSA signature algorithm. Because every user depended on the same cryptographic model, changing the signature scheme required a network-wide hard fork.

EIP-4337 changed this structure, allowing accounts to function like smart contracts. Each account can define its own signature verification logic, enabling users to adopt alternative signature schemes without modifying the entire network. Signature algorithms can now be replaced at the account level, not through protocol-wide upgrades.

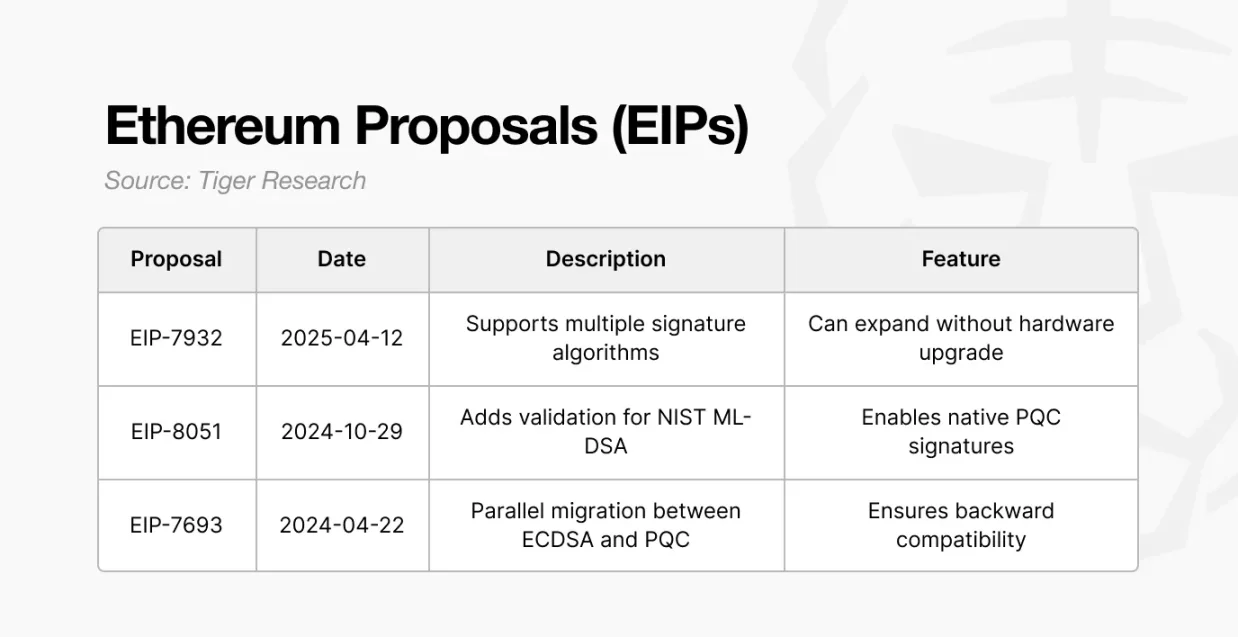

Building on this, several proposals supporting PQC adoption have emerged:

-

EIP-7693: Introduces a hybrid migration path, supporting gradual transition to PQC signatures while maintaining ECDSA compatibility.

-

EIP-8051: Applies NIST PQC standards on-chain to test PQC signatures under real network conditions.

-

EIP-7932: Allows the protocol to recognize and validate multiple signature algorithms simultaneously, letting users choose their preferred method.

In practice, users with ECDSA-based wallets can migrate to Dilithium-based PQC wallets as quantum threats draw near. This transition occurs at the account level and does not require replacing the entire chain.

In summary, Bitcoin aims to integrate PQC in parallel while preserving its current structure, whereas Ethereum is redesigning its account model to directly incorporate PQC. Both pursue the same quantum-resistant goal, but Bitcoin relies on conservative evolution, while Ethereum adopts structural innovation.

While Blockchains Debate, the World Has Already Changed

Global internet infrastructure has already begun transitioning to new security standards.

Web2 platforms supported by centralized decision-making act quickly. Google began defaulting to post-quantum key exchange in Chrome browsers in April 2024, deploying it across billions of devices. Microsoft announced an organization-wide migration plan aiming for full PQC adoption by 2033. AWS started using hybrid PQC by the end of 2024.

Blockchains face a different situation. Bitcoin’s BIP-360 is still under discussion, and Ethereum’s EIP-7932 has been submitted for months but lacks a public testnet. Vitalik Buterin has outlined a gradual migration path, but it remains unclear whether the transition can be completed before quantum attacks become practically feasible.

A Deloitte report estimates that about 20% to 30% of Bitcoin addresses have already exposed their public keys. They are currently safe, but once quantum computers mature in the 2030s, they may become targets. If the network attempts a hard fork at that stage, the likelihood of a split is high. Bitcoin’s commitment to immutability, while foundational to its identity, also makes rapid change difficult.

In the end, quantum computing presents both a technical and a governance challenge. Web2 has already begun its transition. Blockchains are still debating how to start. The decisive question will not be who moves first, but who can complete the transition securely.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News