Randy Research: White Paper on Criminal Cases Involving Virtual Currency Over the Past Five Years

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Randy Research: White Paper on Criminal Cases Involving Virtual Currency Over the Past Five Years

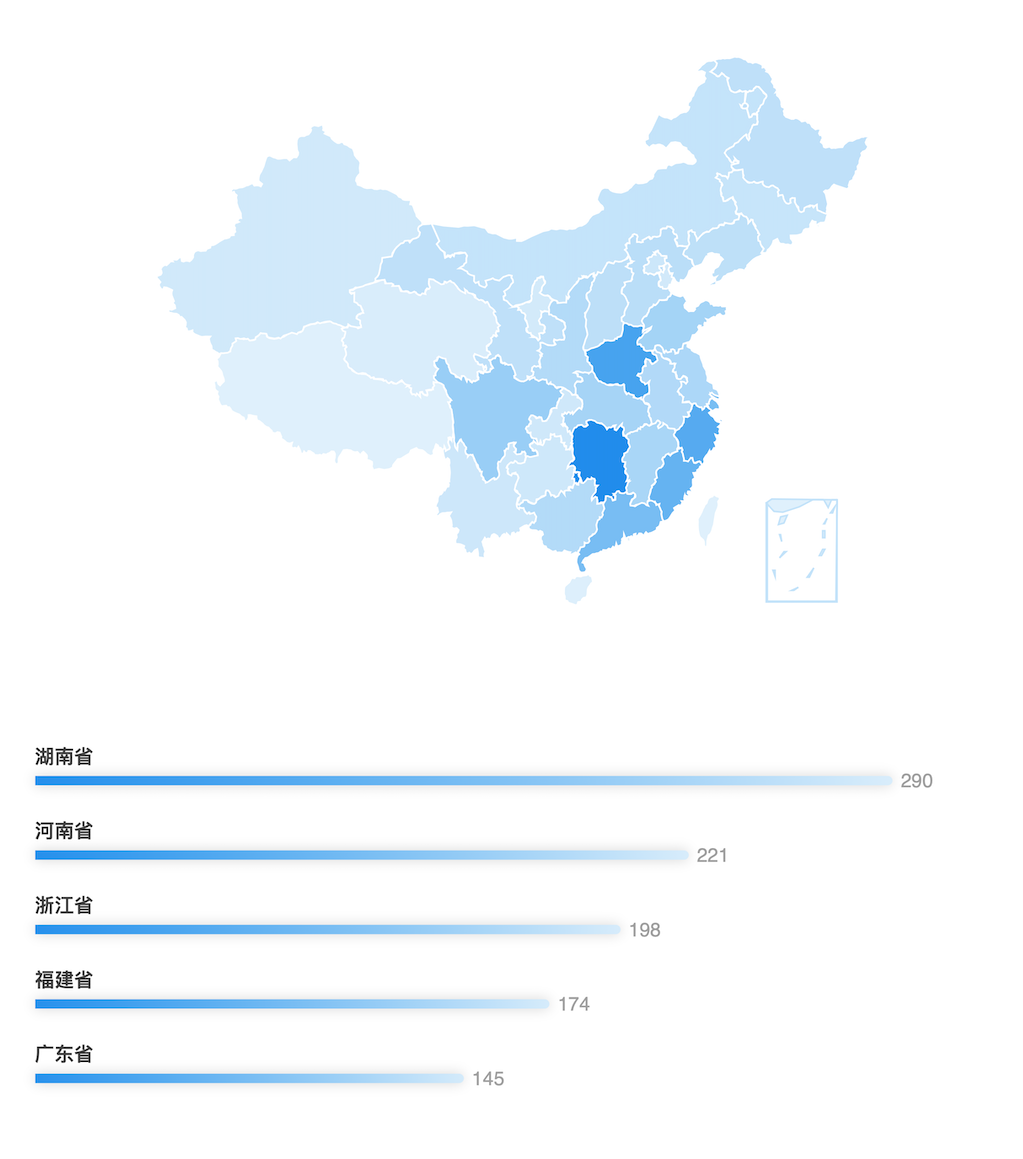

Hunan Province had the highest number of cases among all publicly disclosed cases, followed by Henan Province, Zhejiang Province, with Fujian Province and Guangdong Province closely following.

Since 2013, China has introduced a series of regulatory policies targeting various risks associated with transactions and investments in virtual currencies such as Bitcoin. Despite increasingly stringent regulations, activities related to virtual currency trading and investment have not ceased but have instead shifted from public to private channels and moved from domestic operations to overseas jurisdictions. During this process, numerous illegal actors have emerged. In particular, in recent years, fraudulent activities conducted under the guise of issuing virtual currencies have become rampant. Additionally, due to characteristics such as anonymity and borderless nature inherent in virtual currency circulation, virtual currencies themselves have become new tools for money laundering crimes. Indeed, crimes involving virtual currencies have become one of the most typical and prominent issues within blockchain-related crime and even broader cybercrime domains. This report aims to reveal criminal risk exposure during virtual currency issuance and trading processes for OTC market participants and investors.

After an in-depth analysis of cases involving virtual currency crimes in China between 2019 and 2024, our team has compiled the "White Paper on Criminal Case Judgments Involving Virtual Currencies Over the Past Five Years." Combining significant representative cases from judicial practice and our team's practical experience handling cases over the past two years, we provide targeted defense strategies and compliance recommendations for frequently occurring types of virtual currency-related crimes.

I. Overall Analysis of Virtual Currency-Related Criminal Cases in the Past Five Years

(I) Data Sources and Analytical Methods

To understand how virtual currency-related criminal cases are adjudicated in practice, this paper uses judgment-based statistical analysis to examine relevant case law. Data is presented in tabular form to facilitate comparative categorization. The search was conducted using Alpha Law Database with keywords “virtual currency,” “criminal,” and “first-instance judgment,” retrieving publicly available cases nationwide from 2019 to 2024, resulting in 2,206 legal documents. Due to limitations in sample size and methodology, there may be some inaccuracies in the data statistics and conclusions presented herein, which should be used for reference only.

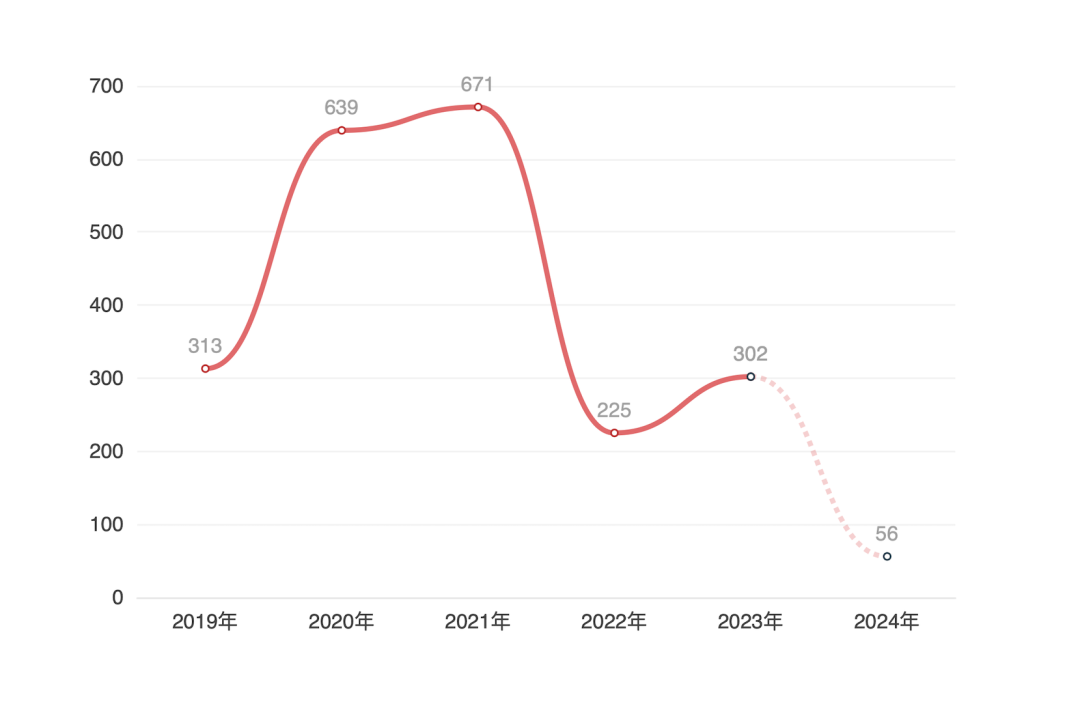

(II) Case Volume Statistics

As of June 10, 2024, WeLegal database disclosed 2,206 virtual currency-related criminal cases from 2019 to 2024. From 2019 to 2021, the number of such cases increased annually, peaking in 2021. In 2022, the number significantly decreased compared to the previous year. There was slight growth in 2023, but overall numbers remain lower than those before 2021. One possible explanation is that increasing domestic crackdowns on virtual currency activities have raised public awareness of potential legal risks involved in issuing or trading virtual currencies. Consequently, such activities have either declined or adopted more covert forms—such as shifting operations overseas—making suspect identification, evidence collection, and fund tracing more difficult, thereby reducing reported crime rates. Another factor could be that ongoing cases require time for litigation procedures; thus, court judgments from the last two years will likely appear in public records after delays of one year or longer.

(III) Geographic Distribution of Cases

Among the 2,206 publicly disclosed virtual currency-related criminal cases, Hunan Province had the highest number of incidents, followed by Henan Province, Zhejiang Province, Fujian Province, and Guangdong Province. It can be concluded that Henan, the Pearl River Delta region, and the Yangtze River Delta region are high-incidence areas for such crimes.

(IV) Current Situation of China’s Crackdown on Virtual Currency Crimes

Since the release of the "Notice on Preventing Bitcoin Risks" in December 2013, Bitcoin has been clearly defined as non-government-issued, lacking legal tender status, and not genuine currency—it is considered a specific type of virtual commodity. For over a decade, China has maintained this view regarding the fundamental attributes of virtual currencies. Since then, regulatory authorities have issued a series of additional regulatory documents. Currently, the most authoritative and important policy governing virtual currencies in China is the "Notice on Further Preventing and Addressing Risks of Virtual Currency Trading and Speculation," jointly released on September 15, 2021, by ten agencies including the Supreme People’s Court, Supreme People’s Procuratorate, Ministry of Public Security, and the People’s Bank of China (commonly referred to in practice as the "September 24 Notice"). The notice explicitly states:

(1) Virtual currencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Tether (USDT) are not official currencies and lack legal tender status, and therefore cannot circulate or be used as money in the market;

(2) Business activities related to virtual currencies constitute illegal financial activities and will be subject to criminal liability if they meet the criteria for crimes. These include: exchanging fiat currency for virtual currency, exchanging between different virtual currencies, acting as a central counterparty in buying/selling virtual currencies, providing information intermediation and pricing services for virtual currency transactions, token issuance financing, and virtual currency derivatives trading. This provision serves as the core basis for current judicial treatment of whether virtual currency activities may involve illegality or criminality;

(3) Overseas exchanges providing services to residents within China constitute illegal financial activities;

(4) Residents in China bear full responsibility for risks when investing in virtual currencies. If such investment behaviors disrupt financial order or endanger financial security, legal liabilities must be assumed.

In particular, in recent years, the anonymity and convenience of virtual currencies have made them ideal tools for criminals seeking to launder, transfer, or move funds across borders. These activities often intertwine with telecom fraud, online gambling, drug trafficking, and other criminal acts, posing serious threats to financial order and social safety. On December 11, 2023, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange jointly issued eight typical cases punishing foreign exchange-related criminal offenses. These primarily involved illegal business operations (specifically illegal foreign exchange trading), foreign exchange fraud, and related charges such as aiding information network crime activities, export tax rebate fraud, and falsifying value-added tax invoices. Among these, using virtual currencies as a medium for RMB-foreign exchange conversion has emerged as a frequent and prominent pattern of illicit foreign exchange trading.

At a press conference held by China’s Supreme People’s Procuratorate in 2024, Vice Prosecutor-General Ge Xiaoyan stated that current cybercrimes are closely linked with emerging technologies and business models, and black-and-gray industries are rapidly evolving. New types of cybercrime exploiting buzzwords like metaverse, blockchain, and binary futures platforms continue to emerge, making virtual currencies fertile ground for breeding and enabling cybercrime.

Additionally, officials from the Inspection Department of China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange emphasized that the Central Financial Work Conference stressed treating risk prevention as an eternal theme in financial work. Moving forward, SAFE will strictly enforce laws, take decisive action, and collaborate with judicial organs to maintain high-pressure打击 against illegal cross-border financial activities.

II. Adjudication Status of Virtual Currency-Related Criminal Cases in the Past Five Years

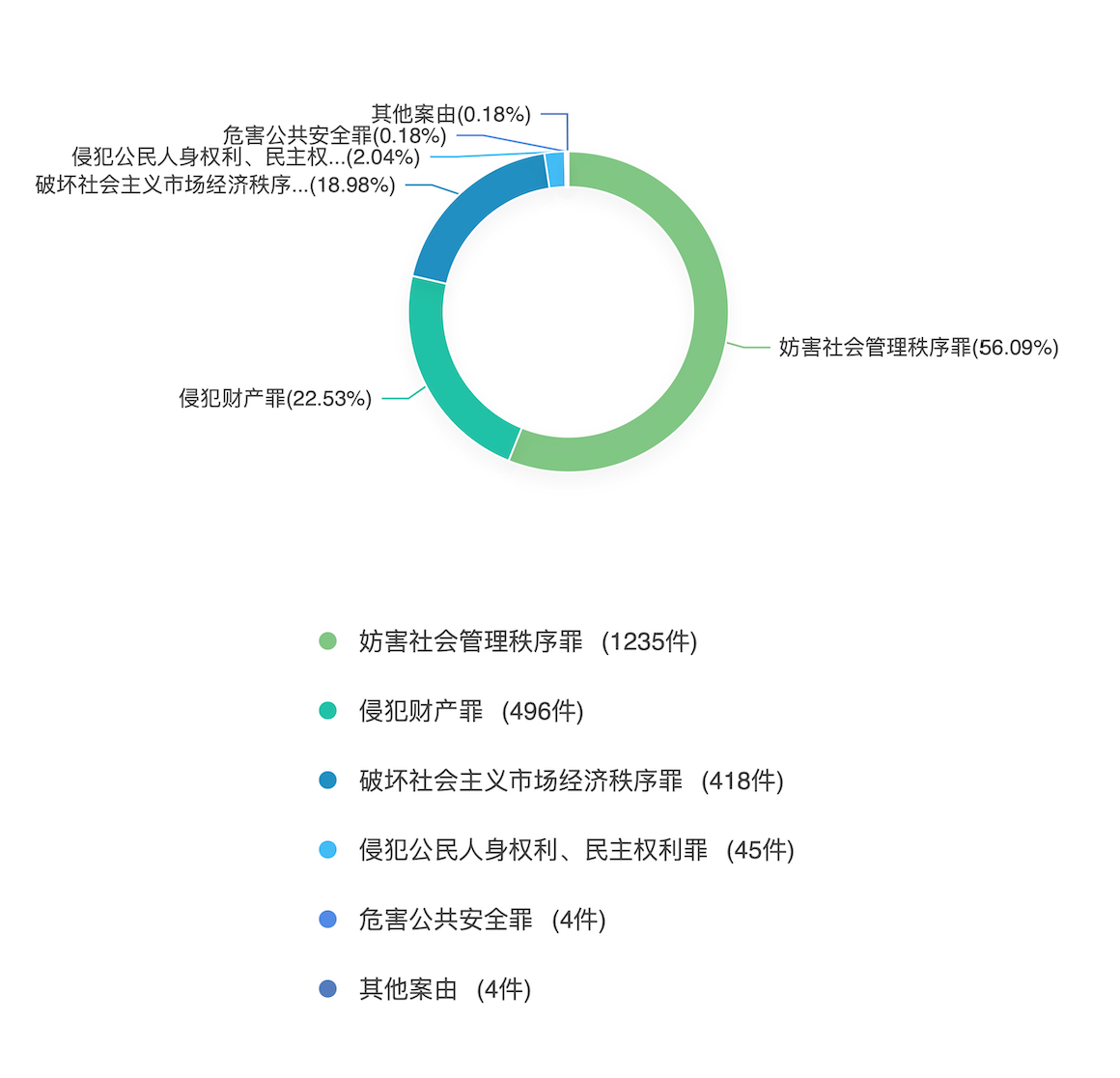

(I) Cause-of-Action Analysis

In terms of causes of action, virtual currency-related crimes span multiple categories including crimes hindering social management order, property infringement, and disrupting socialist market economic order. Major charges include fraud, concealing or hiding proceeds of crime, organizing and leading pyramid schemes, operating gambling establishments, theft, illegally absorbing public deposits, fundraising fraud, illegally obtaining computer system data, illegal business operations, and money laundering.

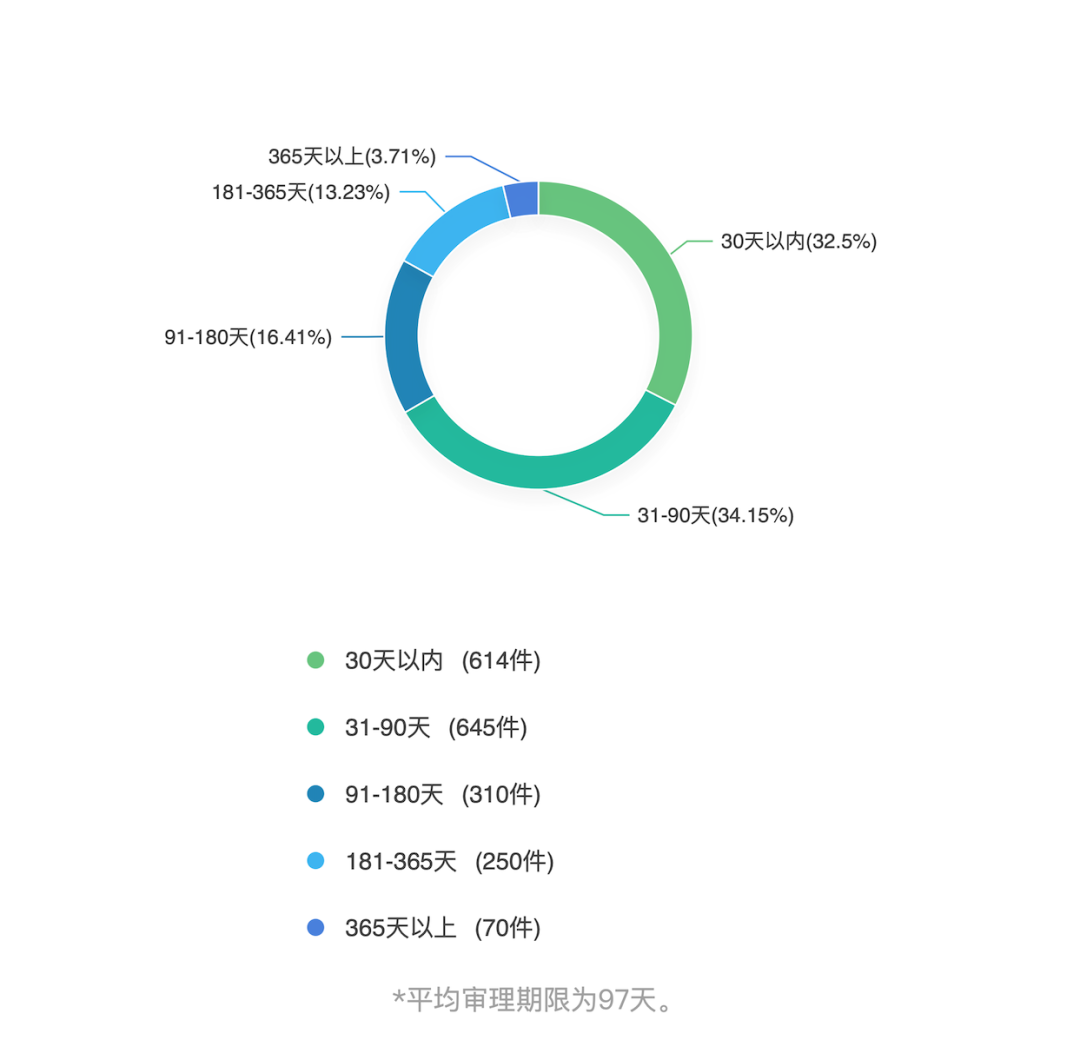

(II) Trial Duration

Regarding trial duration, the majority of cases were resolved within 90 days, while very few exceeded 365 days, with an average trial period of 97 days.

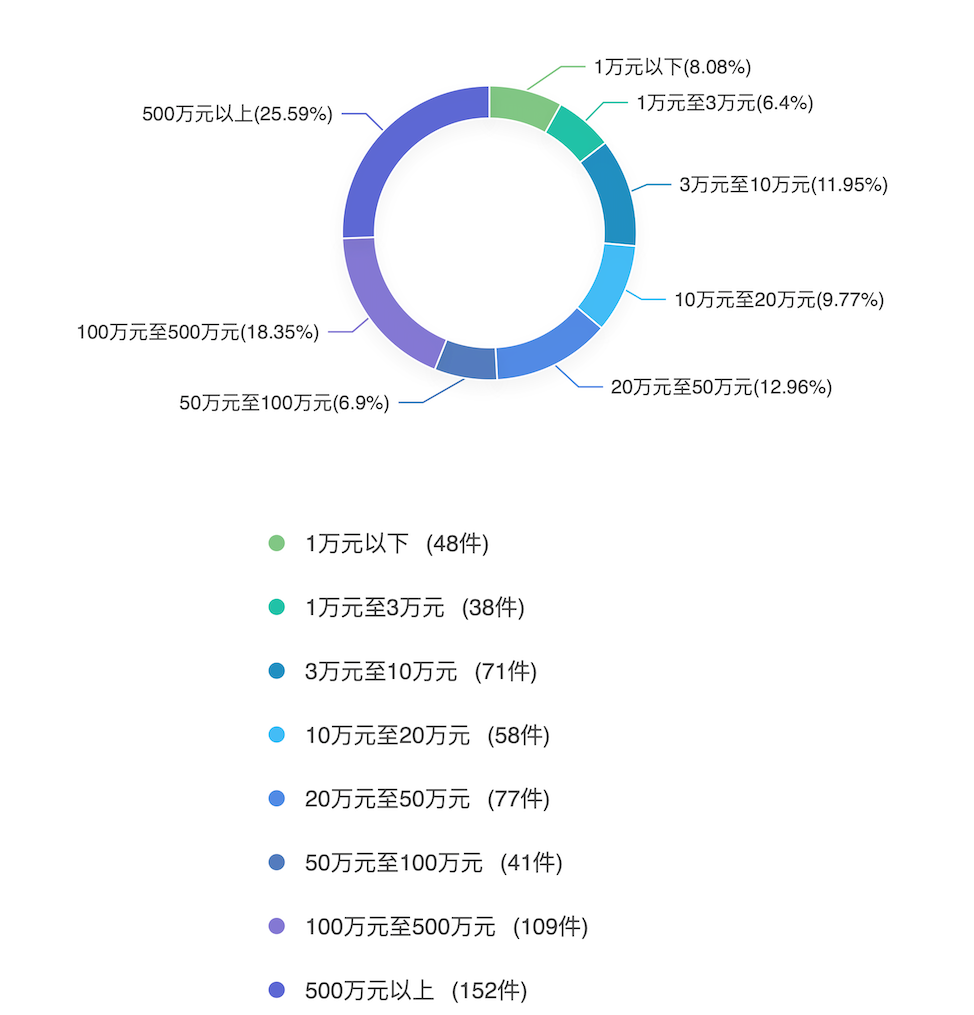

(III) Amount Involved

In terms of the amount involved, 109 cases involved sums between RMB 1 million and RMB 5 million, accounting for 18.35% of total cases. Cases exceeding RMB 5 million accounted for 25.59%, the highest proportion. Clearly, virtual currency-related criminal cases typically involve large amounts of money.

(IV) Sentencing Distribution

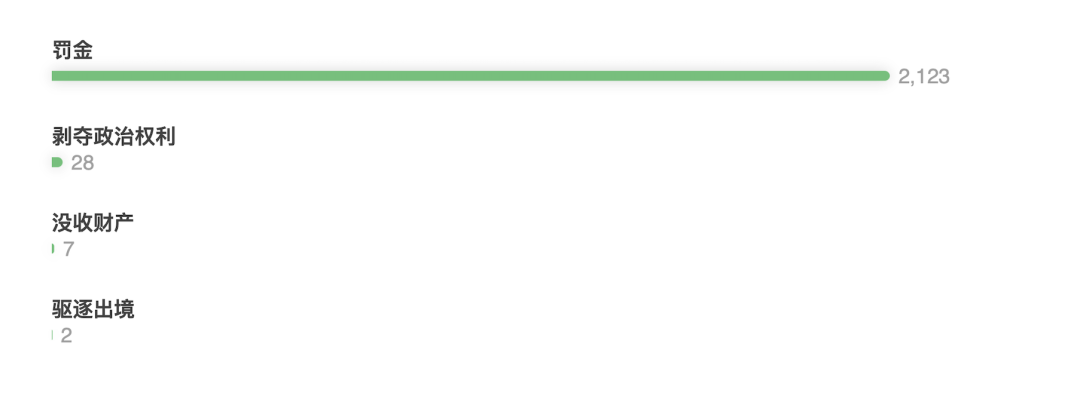

Based on a review of 2,206 virtual currency-related criminal cases over the past five years, five cases resulted in life imprisonment. Most cases received fixed-term imprisonment plus fines, comprising over 90% of all cases, with a small number receiving short-term detention. Overall, penalties for virtual currency-related crimes tend to be severe.

III. Crime-Specific Analysis and Legal Controversies in Virtual Currency-Related Criminal Cases

Currently, based on judicial practice, virtual currency-related crimes can generally be categorized into three types: using virtual currencies as tools to commit other crimes, illegally issuing virtual currencies, and illegally acquiring virtual currencies. Details are as follows:

(I) Using Virtual Currencies as Tools to Commit Other Crimes

1. Money Laundering

In recent years, various crimes involving virtual currencies have surged, particularly money laundering through virtual currencies. According to monitoring data from Chengdu ChainSecurity’s Blockchain Security Situational Awareness Platform, global losses from virtual currency money laundering exceeded RMB 27.366 billion in 2023. Furthermore, in the recent investigation of the world’s largest money laundering case, British police seized over 61,000 Bitcoins worth approximately £3.4 billion.

Similarly, abuse of virtual currencies has drawn significant attention from Chinese government and regulators. Due to their anonymity and ease of use, virtual currencies have become ideal tools for criminals to launder, transfer, and conduct cross-border financial operations. These illegal activities are often intertwined with telecom fraud, online gambling, and drug trafficking, severely threatening financial stability and social security.

Common methods of virtual currency money laundering have increasingly shown corporate-style operation trends. To more effectively clean and conceal illicit funds, underground banks, fourth-party payment platforms, third-party guarantee platforms, as well as technical means such as coin mixing, cross-chain transfers, currency exchange, privacy coins, and DeFi applications, are widely used in virtual currency money laundering, making the methods and pathways increasingly complex.

In China, Article 191 of the Criminal Law defines money laundering as a special offense, whose upstream crimes are limited to certain categories: drug-related crimes, organized crime with mafia characteristics, terrorist activities, smuggling, corruption and bribery, disruption of financial management order, and financial fraud. Only proceeds and benefits derived from these crimes qualify as objects of money laundering. Offenders can be individuals or entities. Amendment XI to the Criminal Law added provisions allowing self-laundering behavior to independently constitute money laundering, further expanding its scope. Specifically, common virtual currency money laundering involves three steps: placement, layering, and integration.

Placement: Criminals inject illicit funds into third-party platforms or merchants to initiate laundering. At this stage, they register accounts using fake identities and purchase virtual currencies to channel illegal gains into the laundering pipeline.

Layering: Exploiting the anonymity of virtual currencies, criminals conduct multi-level, complex transactions across multiple accounts to obscure the origin and nature of the illicit funds.

Integration: After multiple transfers and washes, the virtual currencies held by criminals become relatively “clean.” They consolidate or distribute these funds into different wallet addresses and cash out, completing the laundering process.

Furthermore, subjective intent in money laundering can be divided into “self-laundering” and “third-party laundering.” In self-laundering cases, proof of subjective knowledge is unnecessary, whereas in third-party laundering, establishing subjective knowledge remains essential.

According to judicial interpretations including the Supreme People’s Court’s "Interpretation on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in Handling Money Laundering and Other Criminal Cases," and joint interpretations by the two high-level courts and the Ministry of Public Security, the following objective behaviors or facts in virtual currency transactions involving illicit funds may indicate knowing participation:

(1) Illegal use or sale of accounts and personal information: e.g., frequently opening, personally using, or selling bank cards, Alipay, or WeChat accounts for profit; registering shell companies without real operations and selling business licenses or corporate bank accounts; purchasing phone cards under false identities for bulk usage or resale. Such accounts and information are used in virtual currency money laundering.

(2) Conducting transactions via multiple unrelated or non-personal accounts: Recruiting unidentified individuals daily as “straw men” or “card farmers” through advertisements or referrals to provide Alipay, WeChat, bank accounts, and ID documents. Upstream criminal funds are received through multiple such accounts and then transferred via purchasing and gifting virtual currencies.

(3) Converting assets or cashing out at明显 unreasonable prices or fees: Receiving transaction fees or sale prices significantly higher than market rates when trading Bitcoin or USDT, converting upstream criminal proceeds into Bitcoin and transferring to designated criminal accounts.

(4) Frequent testing of connected accounts and abnormal speed of fund flow: Regularly conducting small test transfers on bank cards to ensure they are not frozen; quickly purchasing virtual currencies or transferring funds upon receipt to avoid seizure.

(5) Frequently adopting concealed internet access, encrypted communications, or data destruction to evade supervision: Long-term and repeated deletion of electronic data from phones and computers; using false identities, frequently changing transaction locations, IP addresses, SIM cards; separating personnel from devices, installing surveillance cameras; using encrypted communication with upstream buyers and associates to avoid detection.

(6) Providing specialized programs, tools, or technical support for illegal purposes: Illegally setting up fourth-party payment systems or virtual currency trading platforms; specifically helping unfreeze suspended WeChat accounts; offering proxy software to hide real IP addresses.

(7) Continuing transactions despite obvious anomalies or after complaints/warnings: After a bank card suspected of criminal activity is frozen by judicial authorities, continuing transactions using alternative cards or methods; failing to cease operations after warnings or reports against virtual currency promotion or information platforms.

2. Illegal Business Operations

The foreign exchange market is a vital component of China's financial system. Legally combating illegal foreign exchange trading and similar criminal activities, preventing external shocks, and maintaining stable FX market operations are key to safeguarding national financial security. Currently, cross-border offset-type illegal foreign exchange trading—a typical form of illegal forex trading—poses challenges in investigation and characterization due to its professionalism, concealment, and diversity, disrupting normal FX market order and undermining China's financial stability.

On December 11, 2023, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange jointly released eight typical cases punishing foreign exchange-related crimes, mainly involving illegal business operations (in the context of illegal foreign exchange trading) and foreign exchange fraud. Related charges also included aiding information network crime activities, export tax rebate fraud, and falsifying VAT invoices. Notably, using virtual currencies as a medium for RMB-foreign exchange conversion has become a frequent and prominent method in recent illegal foreign exchange trading activities.

Currently, the typical method in illegal foreign exchange trading cases is “offset trading.” In such cases, perpetrators collect RMB domestically from clients and deposit equivalent foreign currency into clients’ designated overseas bank accounts, achieving unidirectional fund circulation between domestic and overseas markets. Although no direct exchange of RMB and foreign currency occurs, the economic effect equals foreign exchange trading. Common scenarios include international payment settlement where criminals collude with overseas individuals, enterprises, or institutions, or use overseas bank accounts to assist others in cross-border remittances and fund transfers. These underground banks are known as “offset-type” money changers—funds circulate unidirectionally across borders without physical movement, typically balanced through reconciliation (“dual-location balance”). Under this model, neither RMB nor foreign currency physically crosses borders, appearing as unilateral domestic and overseas fund flows. However, such activities essentially represent disguised foreign exchange trading, still harming the normal order of the foreign exchange market.

On December 11, 2023, among the eight exemplary cases jointly issued by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and SAFE, two involved this new offset-conversion model.

Typical Case One

From February 2019 to April 2020, Zhao organized Zhao Moupeng, Zhou Kaikai, and others to offer AED-RMB exchange and payment services in the UAE and mainland China. The group collected AED cash in Dubai, transferred equivalent RMB to clients’ domestic accounts, purchased USDT (a USD-pegged stablecoin) locally with AED, then immediately sold the USDT illegally through their domestic network to recover RMB, creating a circular funding loop between countries. By profiting from exchange rate differences, the gang earned over 2% per transaction. Investigations revealed that from March to April 2019, the exchanged amount reached over RMB 43.85 million, generating profits totaling over RMB 870,000.

On March 24, 2022, the Xihu District People’s Court of Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, sentenced Zhao to seven years in prison and a fine of RMB 2.3 million; Zhao Moupeng to four years and RMB 450,000; and Zhou Kaikai to two and a half years and RMB 250,000.

Significance

Using virtual currencies as a medium to convert RMB and foreign exchange constitutes the crime of illegal business operations. When individuals exploit the unique properties of virtual currencies to bypass state foreign exchange controls—achieving value conversion between foreign currency and RMB via “foreign currency → virtual currency → RMB”—this constitutes disguised foreign exchange trading and should be prosecuted accordingly under illegal business operation statutes.

Typical Case Two

From January 2018 to September 2021, Chen Guoguo, Guo Zhaozhao, and others built websites such as “TW711 Platform” and “Huosu Platform,” using USDT as a medium to provide foreign currency-RMB exchange services. Customers placed orders on these sites for top-ups or payments, sending foreign currency to designated overseas accounts. The site used the foreign currency to buy USDT abroad, which Fan Moupin then sold through illegal channels to obtain RMB, paying clients’ designated domestic third-party payment accounts at agreed exchange rates, earning spreads and service fees. The platforms illegally exchanged over RMB 220 million.

On June 27, 2022, Baoshan District People’s Court of Shanghai sentenced Guo Zhaozhao to five years in prison and a fine of RMB 200,000; Fan Moupin to three years and three months and RMB 50,000; Zhan Jixiang to one year and six months and RMB 5,000 for aiding information network crime activities; and Liang Zuanzuan to ten months and RMB 2,000.

Significance

In China, virtual currencies do not possess legal status equal to fiat money. However, facilitating indirect illegal conversion between domestic and foreign currencies via virtual currencies represents a critical link in foreign exchange crime chains and should be legally punished. Those who conspire beforehand with illegal foreign exchange traders or knowingly assist them in converting currencies through virtual currency transactions constitute co-offenders in illegal business operations. Those who provide virtual currency trading services to illegal foreign exchange traders but only generally recognize the underlying illegality—not specifically knowing it involves foreign exchange crimes—may be charged with aiding information network crime activities.

In fact, since the People’s Bank of China and five other departments issued the "Notice on Preventing Bitcoin Risks" in 2013, relevant departments have gradually introduced regulations to prevent risks associated with token issuance financing. In 2021, ten departments including the PBOC released the "Notice on Further Preventing and Addressing Risks of Virtual Currency Trading and Speculation," clarifying that virtual currencies lack legal equivalence to fiat money and that related business activities are illegal financial activities. Using virtual currencies as transaction media to achieve value conversion between foreign currency and RMB—including RMB-to-virtual-currency-to-foreign-currency or vice versa—is deemed disguised foreign exchange trading.

Criminally, according to Article 4 of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress' "Decision on Punishing Crimes of Fraudulent Foreign Exchange Purchases, Capital Flight, and Illegal Foreign Exchange Trading" and Article 225 of the Criminal Law, along with Article 2 of the 2019 interpretation by the two high-level courts on handling illegal capital settlement and foreign exchange trading cases, any act of disguised foreign exchange trading that seriously disrupts financial market order shall be deemed illegal business operations if circumstances are severe. Thus, circumventing state foreign exchange regulation by indirectly converting foreign currency and RMB through virtual currencies, when severe, constitutes illegal business operations. However, in individual determinations, factors such as whether operators aim for profit, engage in continuous operations, and whether actual currency conversion occurs must be comprehensively assessed to determine criminal liability.

Moreover, depending on whether cross-border fund movements involve proceeds of crime, using virtual currencies as transaction media may also violate money laundering, concealing or hiding proceeds of crime, or related charges. If both illegal business operations and these charges apply, prosecution will follow the more severe penalty.

(II) Crimes Involving Illegal Issuance of Virtual Currencies

1. Illegal Absorption of Public Deposits

Under China’s Criminal Law, the crime of illegal absorption of public deposits refers to acts violating national financial management laws by raising funds from the general public (including entities and individuals), thereby disrupting financial order. Four main elements define such acts:

(1) Raising funds without legal approval from competent authorities or under the guise of legitimate operations;

(2) Publicly promoting through media, seminars, flyers, text messages, etc.;

(3) Promising repayment of principal with interest or returns in currency, goods, equity, etc., within a specified period;

(4) Raising funds from unspecified members of the public.

In virtual currency issuance, issuers typically solicit mainstream virtual currencies like Bitcoin, Ethereum, or USDT rather than fiat currency. Traditionally, the protected interest in illegal deposit absorption centers on commercial banks’ exclusive right to issue currency. Seemingly, only when the target is fiat currency does this exclusivity get infringed, posing serious threats to financial order. However, since solicited virtual currencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum lack legal tender status, they fall outside the scope of this offense.

Yet in actual issuance, investors often first purchase mainstream virtual currencies from dealers using RMB. Choosing mainstream virtual currencies as fundraising targets serves dual purposes: avoiding regulatory scrutiny (since most countries don’t recognize them as legal tender) and leveraging their stability and liquidity. Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple, and USDT (pegged to USD) rank among the most valuable and stable digital tokens, widely exchangeable for fiat in many countries. Given the operational costs of security token projects, the ability to reconvert raised virtual currencies into fiat makes them functionally equivalent to indirect financial instruments. Ultimately, fundraising still hinges on fiat value benchmarks. Hence, collecting mainstream virtual currencies from the public may still trigger liability under the crime of illegal absorption of public deposits.

2. Fundraising Fraud

Fundraising fraud requires both intent to unlawfully possess and use of fraudulent methods to raise funds. Practically, project initiators often promote project points or self-created “air coins” as investment vehicles, luring public investment with promises of high returns. Objectively, this manifests in several ways:

First, promoted virtual currencies may not be genuine cryptocurrencies—even falling short of being altcoins. Often, promoters fabricate facts, exaggerate foreign tech teams, and hype commercial potential while having no real operations tied to the virtual currency.

Second, offering high-return incentives is common. Distributing free “candy” (valuable virtual currencies upon registration) rapidly attracts new users.

Third, manipulating virtual currency prices for profit. Project teams often set up proprietary trading platforms, artificially inflating trading volume to create illusions of market vitality and attract investors. They manipulate price trends behind the scenes, establish insider trading ("rat trading"), drive prices up initially to lure investors, then crash prices far below purchase levels to secure massive profits.

Subjectively, such promoted virtual currencies aren’t authentic blockchain-based assets but merely tools for illegal fundraising. These pseudo-coins rarely list on exchanges, lack technological or trading value, and never achieve commercial viability—they serve solely as mechanisms for controlling capital pools. With intent to defraud and using deception to lure unspecified individuals into investing through public promotions promising high returns, such actions fully satisfy the constituent elements of fundraising fraud.

3. Organizing and Leading Pyramid Schemes

Taking the Plus Token case—a virtual currency pyramid scheme involving RMB 14.8 billion—as an example, the platform classified members into five tiers: regular member, major player, influencer, god, and creator, based on recruitment numbers and investment amounts. The platform advertised an “intelligent dog arbitrage” feature (earning spreads via arbitrage trading), attracting members by promising value-added currency services. Entry required paying over $500 worth of cryptocurrency and activating the “intelligent dog” to earn platform returns.

Members formed hierarchical structures based on referral sequences. Rewards were distributed based on the number of recruited subordinates and invested funds, calculated via three methods: intelligent arbitrage earnings, referral bonuses, and executive rewards—all directly or indirectly tied to recruitment volume and investment size. Therefore, charging entry fees, recruiting downlines, and tiered compensation align closely with Article 224-1 of the Criminal Law defining organizing and leading pyramid schemes. Both Jiangsu courts ruled the defendants guilty of this charge.

Specifically, Article 224-1 of the Criminal Law defines the offense as follows:

(1) Under the pretense of selling products or providing services, requiring participants to pay fees or purchase goods/services to join, forming hierarchical levels in sequence.

(2) Directly or indirectly basing compensation or rebates on the number of recruits, enticing or coercing participants to recruit others, thereby defrauding property and disrupting socioeconomic order.

(3) As per Provision No. 78 of the Procuratorate and MPS "Standards for Filing and Prosecution of Criminal Cases (II)," the activity must involve at least 30 people across three or more levels.

In practice, as China tightens virtual currency regulation, many crypto projects evade oversight by leveraging online communities and referral marketing. These behaviors exhibit core features of pyramid schemes:

(1) Deceptiveness: Promoted business activities are actually fronts using blockchain or virtual currencies, with promised returns funded by participants’ entry fees.

(2) Compensation model: Paying rewards based directly or indirectly on recruitment numbers. Participants recruit others, building downward chains and earning commissions based on subordinate recruitment counts.

(3) Hierarchical structure: Typically structured as pyramids with broad bases narrowing upward, segmented by entry order and recruitment volume.

(III) Crimes Involving Illegal Acquisition of Virtual Currencies

There has long been significant debate in judicial and academic circles over whether stealing Bitcoin should be prosecuted as theft or as illegally obtaining computer system data. In 2022, an article titled "Criminal Characterization of Illegally Stealing Bitcoin" published in *Chinese Procurators*—a national legal journal sponsored by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and hosted by the National Prosecutors College—concluded: “Post-September 2021, such acts cannot be regulated as property crimes. Without being covered by other offenses such as illegally obtaining computer system data, criminal liability cannot be established.”

In reality, consensus on the nature of virtual currencies remains elusive. For instance, on May 5, 2022, the Shanghai High People’s Court’s official account “Pujiang Tianping” highlighted a model case explicitly stating that Bitcoin qualifies as virtual property with asset attributes protected under property rights law. In that ruling, recognizing Bitcoin’s legal nature was foundational for enforcing judgments. The first-instance court noted Bitcoin exhibits value, scarcity, and controllability—meeting criteria as a rights object and fitting the definition of virtual property. The Shanghai High Court observed widespread academic debate over Bitcoin’s legal nature, noting attempts to fit it into traditional civil rights theories fail. Instead, answers must come from judicial practice.

The court cited several precedents recognizing Bitcoin as virtual property: Wu v. Shanghai Yaozhi Network Technology Co., Ltd. & Taobao Network Co., Ltd. [(2019) Zhe 0192 Min Chu No. 1626], Li & Brandon Schmidt v. Yan [(2019) Hu 01 Min Zhong No. 13689], Chen v. Zhang [(2020) Su 1183 Min Chu No. 3825]. Courts found Bitcoin generated through “mining,” requiring equipment purchases, maintenance, and energy costs, demonstrating economic value. Its supply cap of 21 million ensures scarcity. Holders can possess, use, profit from, and dispose of Bitcoin, fulfilling controllability requirements. The Shanghai High Court stated: “Courts adopt pragmatic approaches, refraining from definitively classifying the legal nature of virtual property. Given its economic value and alignment with property traits, it is protected under property rights rules.”

In civil matters, on December 27, 2022, the Supreme People’s Court issued Guiding Case No. 199, affirming that “an arbitration award ordering compensation equivalent to Bitcoin in USD, later converted to RMB, indirectly supports兑付transactions between Bitcoin and legal tender, violating state financial regulations on virtual currencies and undermining public interest. Such awards should be annulled.”

Moreover, a recent report by The Paper titled “First Criminal Case Involving Virtual Currency Issuance Sparks Debate: Does Removing Liquidity Causing Investor Losses Constitute Fraud?” detailed how a senior college student was sentenced to four and a half years for fraud after launching a virtual currency and withdrawing liquidity. The court found him guilty of fraud, implicitly acknowledging the property nature of virtual currencies by supporting兑付between virtual and legal tender.

(IV) Other Crimes

In a December 2021 ruling by the Zhuzhou Intermediate Court in Hunan Province, from December 2018 to February 2019, Li, employed by a Shenzhen company, bought USDT on Huobi, transferred it to the “pex” order-placing platform for resale. He listed slightly above Huobi purchase prices—about two cents higher per unit—to earn spreads. Over time, several of his receiving bank cards were successively frozen by police, and his employer dissolved. Nevertheless, Li continued reselling, recruiting three others to join him on pex. Upon investigation, the four suspects admitted why buyers willingly paid premiums on lesser-known, pricier platforms: their funds were illegal. Each time proceeds arrived, cards risked freezing due to illicit origins. Yet given substantial profits, they took the risk. Authorities verified over RMB 38 million in unilateral transaction volume across more than twenty cards used by Li et al., with over RMB 300,000 in victim funds flowing through their accounts. The four earned RMB 107,200 collectively and were convicted of aiding information network crime activities.

Article 287-2 of the Criminal Law defines aiding information network crime activities as knowingly providing internet access, server hosting, cloud storage, communications transmission, advertising promotion, payment settlement, or other assistance to others engaged in cybercrime, under serious circumstances, punishable by up to three years in prison or detention, with or without fines.

Per Article 12 of the Interpretation by the Supreme People’s Court and Supreme People’s Procuratorate on Handling Criminal Cases Involving Illegal Use of Information Networks and Aiding Information Network Crime Activities, “serious circumstances” include:

(1) Assisting three or more parties;

(2) Payment settlement exceeding RMB 200,000;

(3) Funding via ads or similar exceeding RMB 50,000;

(4) Illegal gains exceeding RMB 10,000;

(5) Having prior administrative penalties within two years for illegal use of information networks, aiding cybercrime, or compromising computer system security, and repeating such acts;

(6) Resulting in serious consequences from assisted crimes;

(7) Other serious circumstances.

In this case, Li and others opened multiple bank cards under personal IDs to trade USDT on “pex” and receive RMB. Although “pex” offered higher virtual currency prices and was prone to illicit funds, they chose to operate there. When transacting with fraudsters, they sold USDT and directly provided bank accounts as primary recipients of stolen funds. Whether such acts constitute “payment settlement” warrants discussion.

Article 3 of the Measures for Payment Settlement (Yin Fa [1997] No. 393) defines payment settlement, but virtual currency trading isn't included. Moreover, rulings lacked clear legal basis for characterizing such trades as “payment settlement.” Yet in practice, judicial bodies may expand interpretations of payment settlement.

For conviction under aiding information network crime, the key lies in whether the actor “knew” or “should have known.” Article 11 of the aforementioned interpretation specifies circumstances indicating “knowledge.” While Li and others used non-mainstream platforms, this alone doesn’t prove abnormal behavior. Their transaction fees weren’t unusual. However, continuing transactions after learning the platform handled illicit funds and operations ceased, and persisting despite card freezes, may constitute “knowing” circumstances.

Additionally, distinguishing aiding information network crime from concealing criminal proceeds remains controversial. Key distinctions include:

First, object and method: Aiding information network crime doesn’t require the funds to be criminal proceeds; focus is on assisting upstream crime regardless of fund nature. In contrast, concealing criminal proceeds requires active efforts to transfer, cash out, withdraw, or assist moving assets. The former often involves providing bank cards; the latter entails purposeful concealment or transfer of property.

Second, subjective awareness: Aiding information network crime doesn’t require precise knowledge of whether upstream acts constitute crimes—only recognition of illegal activity suffices. Concealing criminal proceeds demands knowledge that the assets are criminal in origin.

Third, timing of assistance: Concealing criminal proceeds usually occurs post-crime, after illicit funds reach the actor. Aiding information network crime involves pre- or mid-crime help. However, relying solely on timing is problematic, as actors might unknowingly assist payment settlements. Comprehensive evaluation of subjective awareness, object, method, and timing is necessary.

IV. Risk Prevention Alerts and Compliance Recommendations

In summary, due to unclear intrinsic attributes and diverse application scenarios of virtual currencies, numerous charges and controversies arise. Especially in recent years, virtual currencies have increasingly become new tools for money laundering and foreign exchange crimes. Meanwhile, many criminals exploit the public’s limited understanding and expectations of high returns from virtual currencies to create novel scams, severely infringing on citizens’ property rights. Accordingly, China’s regulation of digital currencies and crackdowns on related crimes have clearly trended toward greater severity.

Against this backdrop, as investors standing at the forefront of the digital era, it is difficult to precisely judge whether digital currencies represent genuine value outputs of blockchain technology or another flawed financial mechanism in the information age. Nonetheless, every investor and enterprise must clearly recognize the legal risks behind digital currencies, especially criminal liabilities, and strictly comply with relevant laws and regulations. Only then can risks be minimized, ensuring steady growth in investment and operations.

For platform operators and cryptocurrency dealers, to effectively avoid money laundering risks, businesses can implement measures to ensure transactions are legitimate and authentic. These include requiring buyers to provide genuine transaction records from recent months, ensuring funds remain in accounts for extended periods rather than rapid inflows/outflows. Additionally, merchants can request KYC (Know Your Customer) documentation, preserve WeChat chat logs, and conduct online transfers.

Through these practices, merchants can avoid transactions with straw-man accounts, enabling genuine digital currency trades. Even if illicit funds enter the system, such measures enable quicker identification of true culprits by investigative agencies, protecting oneself from being wrongly accused of aiding money laundering.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News