Officially defined: China’s RWA game rules are now set—RWAs will no longer exist in a gray zone.

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Officially defined: China’s RWA game rules are now set—RWAs will no longer exist in a gray zone.

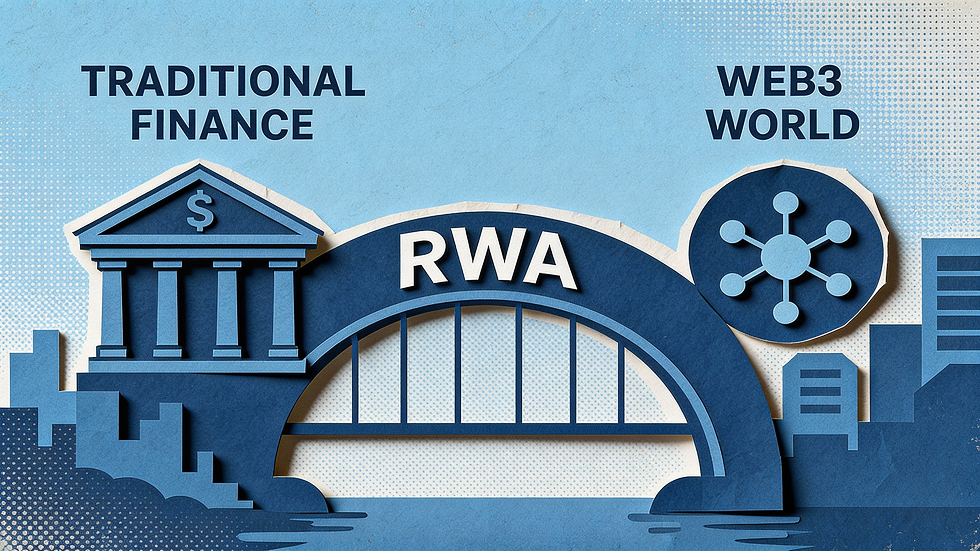

This is not China embracing crypto; rather, it is China embracing tokenization in its own way.

By Bo Cai

February 6, 2026—a date worth remembering.

Today, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), jointly with seven other ministries and commissions—the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), the National Financial Regulatory Administration (NFRA), the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE)—issued the Notice on Further Preventing and Addressing Risks Related to Virtual Currencies and Other Matters (Yinfa [2026] No. 42). Simultaneously, a highly practical annex—the Regulatory Guidelines on Tokenized Asset-Backed Securities Issued Abroad Using Domestic Assets—was also released.

This is not a simple “ban.” If your understanding still stops at “China is banning crypto again,” you’ve likely completely misread this document.

Let me break down both documents in plain language.

Eight ministries issued a similar notice back in 2021—Yinfa [2021] No. 237, commonly known in the industry as the “September 24 Notice.” That notice established China’s policy of “comprehensive containment” toward virtual currencies. Five years later, Article 19 of the new Notice explicitly states: “The Notice on Further Preventing and Addressing Risks Related to Virtual Currency Trading and Speculation (Yinfa [2021] No. 237), jointly issued by the PBOC and nine other departments, is hereby repealed.”

Abolishing the old to establish the new signals that this is not merely a patch—it’s a systemic regulatory overhaul. So what’s the biggest difference between the new and old notices?

One word: RWA.

The 2021 September 24 Notice focused entirely on virtual currencies; at that time, the concept of “RWA” (real-world asset tokenization) barely existed in China’s regulatory lexicon. By contrast, Yinfa [2026] No. 42 devotes substantial space to defining and regulating RWAs—an unmistakable signal that regulators formally recognize RWA as a legitimate business model and intend to set clear rules for it, rather than rejecting it outright.

Key Point One: The stance on virtual currencies remains unchanged—but the wording is more precise

Article 1, Paragraph 1 of Yinfa [2026] No. 42 opens unequivocally: “Virtual currencies do not hold legal status equivalent to that of legal tender.” Bitcoin, Ethereum, USDT, and others are explicitly named and defined as “non-legal-tender instruments that must not—and cannot—circulate or be used as currency in the market.”

Subsequent language closely follows that of the September 24 Notice: “All domestic activities—including fiat-to-virtual-currency exchange, virtual-currency-to-virtual-currency exchange, provision of trading intermediation or pricing services, and initial coin offerings (ICOs)—are strictly prohibited and shall be resolutely abolished in accordance with law.” Services provided to domestic users by overseas entities are likewise banned.

Yet one important new clause appears: “No entity or individual, whether domestic or overseas, may issue RMB-pegged stablecoins abroad without prior approval from relevant competent authorities.” Note the phrasing: “without prior approval,” not “strictly prohibited.” What does this imply? In theory, if such issuance receives formal, lawful, and regulatory-compliant approval, RMB-pegged stablecoins could follow a compliant pathway. The opening is narrow—but it exists.

For virtual currency investors, frankly, there’s little novelty here. What was banned remains banned; what was cracked down on continues to be cracked down on. Mining operations remain under scrutiny; advertising is still suppressed; even company registration names and business scopes may no longer include terms like “virtual currency,” “cryptocurrency,” or “stablecoin.”

Key Point Two: For the first time, an official definition of RWA appears in a ministerial-level document

This is the most noteworthy part of Yinfa [2026] No. 42. Article 1, Paragraph 2 provides an exceptionally clear official definition:

“Real-world asset tokenization refers to activities involving the use of cryptographic and distributed ledger—or similar—technologies to convert ownership rights, income rights, and other rights associated with assets into tokens (or ‘digital tokens’) or other instruments possessing token-like characteristics—including equity or debt certificates—and to issue and trade such instruments.”

This definition carries several critical implications. First, it restricts the technological foundation of RWA to “cryptographic and distributed ledger—or similar—technologies”—i.e., blockchain or blockchain-like technologies are a prerequisite. Second, the scope of assets eligible for tokenization—“ownership rights, income rights, etc.”—is extremely broad, covering everything from real estate and accounts receivable to bonds and fund shares, theoretically all within reach. Third, both the “issuance” and “trading” phases fall squarely under regulatory purview.

However, the true crux lies in the next sentence:

“Activities conducted on designated financial infrastructure platforms, with prior approval from the competent business authority in accordance with law and regulation, are exempted.”

In plain language: RWA is not categorically prohibited within China—but it can only be conducted upon obtaining official authorization and exclusively on financial infrastructure platforms approved by regulators. The phrase “designated financial infrastructure” is particularly telling. What qualifies as “designated financial infrastructure”? The notice does not enumerate specific examples—but based on current practice in China, candidates likely include the Shanghai Data Exchange, the Beijing International Big Data Exchange, the Shenzhen Data Exchange, regional financial asset exchanges, and the PBOC-led digital RMB infrastructure.

In other words, Yinfa [2026] No. 42 doesn’t say “RWA is banned”; it says, “If you want to do RWA, you must do it in my arena.”

Key Point Three: A formal regulatory framework now governs tokenization of domestic assets abroad

Chapter IV of Yinfa [2026] No. 42—“Strict Regulation of Domestic Entities Engaging in Related Activities Abroad”—is the most groundbreaking section of the entire notice. It does not say “you may not go abroad”; rather, it says “you may go abroad—but you must follow the rules.”

Article 14 distinguishes among several scenarios: RWA conducted abroad in the form of foreign debt falls under the NDRC and SAFE; RWA conducted abroad based on domestic rights and resembling asset securitization or equity financing falls under the CSRC; all other forms of RWA fall under the CSRC’s oversight, coordinated with other relevant departments. The core principle is “same business, same risk, same rules”—regardless of whether issuance occurs in Hong Kong or Singapore, Chinese regulators will assert jurisdiction over any RWA whose underlying assets reside in mainland China.

What does this mean? Until now, the biggest obstacle facing Chinese domestic assets seeking cross-border RWA tokenization has never been technology or market demand—but rather the regulatory gray zone. Many project teams wanted to proceed but dared not: lacking explicit rules, their actions risked falling into legal limbo—neither clearly lawful nor clearly unlawful. Yinfa [2026] No. 42 finally spells out the rules: You may proceed—but only after formal approval or filing.

The accompanying Regulatory Guidelines on Tokenized Asset-Backed Securities Issued Abroad Using Domestic Assets (hereinafter the “Guidelines”) further details exactly how to proceed.

Key Point Four: CSRC filing system—concrete pathway established for tokenized asset-backed securities

The Guidelines represent the most operationally significant document of this round, specifically establishing a filing regime for the scenario where “domestic assets serve as the basis for issuing tokenized asset-backed securities abroad.”

The core filing process outlined in the Guidelines is as follows: The domestic entity holding actual control over the underlying assets must file with the CSRC, submitting a filing report, full set of overseas issuance documentation, and complete disclosures covering information on the domestic filer, the underlying assets, and the token issuance plan. Upon receipt of complete and compliant materials, the CSRC completes the filing procedure and publishes the result; noncompliant submissions are rejected.

Note carefully: This is a “filing” system—not an “approval” system. Although the CSRC “may, at its discretion, solicit opinions from relevant State Council departments and sectoral regulatory agencies,” the overall institutional design is based on filing—a significantly more flexible approach than approval. This reflects a cautiously open regulatory stance toward cross-border tokenized asset-backed securities using domestic assets—not a green light, but certainly not a welded-shut door either.

The Guidelines also lay out a clear negative list: assets legally prohibited from financing, assets threatening national security, controlling persons with criminal records, entities currently under investigation, underlying assets entangled in major ownership disputes, and assets already barred under existing domestic asset securitization negative lists—all are disallowed.

These restrictions closely mirror those governing existing domestic asset securitization and overseas listings by Chinese enterprises—indicating that regulators have deliberately integrated RWA tokenization into the established securities regulatory framework, rather than building an entirely new one from scratch.

Key Point Five: Financial institutions’ roles are strictly defined

Article 6 of Yinfa [2026] No. 42 imposes strict requirements on financial institutions: They must not provide account opening, fund transfer, clearing and settlement, or related services for virtual currency–related activities. However, for RWA activities, the restriction applies only to those “undertaken without approval”—meaning that, for compliant RWA activities duly filed or approved, financial institutions are permitted to provide custody, clearing, settlement, and other services.

This distinction carries immense significance for the entire industry. To scale up, RWA projects require active participation from traditional financial institutions—custodian banks, clearing organizations, payment gateways—infrastructure-level players. By explicitly separating “compliant RWA” from the negative label of “virtual currency,” Yinfa [2026] No. 42 removes key policy barriers preventing financial institutions from engaging in RWA business.

Article 15 further stipulates that overseas subsidiaries and branches of domestic financial institutions providing RWA services abroad must operate “in accordance with law and prudently”: they must deploy qualified personnel and systems, implement KYC, suitability management, anti-money laundering (AML), and other requirements, and fully integrate these activities into the compliance and risk-control management systems of their domestic parent institutions. In effect, this tells Chinese financial institutions’ overseas arms: “You may conduct this business—but it must be managed centrally under your group’s unified compliance framework; no regulatory arbitrage abroad.”

How should we interpret the overall message conveyed by these two documents?

Viewing Yinfa [2026] No. 42 and the Guidelines together reveals an exceptionally clear regulatory logic:

First, virtual currencies and RWAs are explicitly decoupled. Virtual currencies remain subject to stringent crackdowns—a position unwavering since 2017. Yet RWAs are no longer lumped generically into the category of “virtual currency–related activities.” Instead, they are treated as a legitimate financial business model capable of operating within a defined regulatory framework.

Second, domestic RWA operates under a “licensed operation” model. Conducting RWA domestically requires doing so exclusively on regulator-approved “designated financial infrastructure.” Absent a license or formal approval, such activity is deemed illegal financial activity—fully consistent with China’s long-standing regulatory philosophy that finance is a licensed industry.

Third, cross-border tokenization of domestic assets adopts a filing-based regime. This represents the single largest incremental development. It establishes a compliant channel through which high-quality domestic assets can access global capital markets via RWA. As the primary regulator, the CSRC employs filing—not approval—resulting in a relatively reasonable threshold.

Fourth, financial institutions’ participation in compliant RWA business receives explicit regulatory sanction. This provides the foundational institutional architecture for building the entire ecosystem. Without banks and clearing institutions, RWA remains mere theoretical abstraction.

From a broader macro perspective, the release of Yinfa [2026] No. 42 and the Guidelines marks China’s formal transition—from “blanket prohibition” to “classified regulation”—in its oversight of crypto assets. Virtual currencies continue to face suppression, while RWAs—especially those backed by real assets, structured with compliance rigor, and subject to regulatory filing—are deliberately carved out from the targets of suppression and brought into the formal financial regulatory system.

This is not China embracing crypto. It is China embracing tokenization—in its own way.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News