Elizabeth Stark: Why Does Bitcoin Need a Lawyer?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Elizabeth Stark: Why Does Bitcoin Need a Lawyer?

Stark's work aims to reshape the way Bitcoin operates, but whether her vision can truly be realized on a global scale remains to be seen.

Author: Thejaswini M A

Translation: Block unicorn

Preface

On a Tuesday in March 2023, trademark litigation struck.

Elizabeth Stark watched as her company’s biggest product launch unraveled. Lightning Labs had spent years building the "Taro" protocol, allowing people to send stablecoins over Bitcoin's Lightning Network. The technology was ready, community excitement high, and key partners prepared.

Then, a judge issued a temporary injunction. Tari Labs claimed ownership of the "Taro" trademark. Lightning Labs had to immediately stop using the name—no more development announcements or marketing activities.

Renaming it "Taproot Assets" took weeks. Months of momentum vanished overnight; partners had to explain the change to confused customers. Questions arose about whether Lightning Labs had conducted adequate trademark research before launching such a major initiative.

But Stark pressed on. The technology continued evolving under its new name, though competitors gained ground during the forced pause.

She has built one of Bitcoin’s most important infrastructure companies. Stark’s work aims to reshape how Bitcoin operates, but whether her vision can truly scale globally remains to be seen.

Before Elizabeth Stark built Bitcoin infrastructure, she learned how to fight opponents far stronger than trademark holders.

Resisting Bad Regulation

Harvard Law School, 2011. Stark organized a grassroots campaign to stop two bipartisan bills from passing Congress.

SOPA and PIPA would have allowed copyright holders to force websites suspected of infringement offline.

What were they?

SOPA (Stop Online Piracy Act) and PIPA (Protect IP Act) were proposed U.S. laws aimed at combating online piracy by allowing rights holders to force websites accused of infringement offline. These bills would enable blocking sites from advertising, payment processing, and search engine services, potentially shutting down even non-U.S.-based websites. Many feared these laws would lead to widespread internet censorship, harming legitimate sites and free speech.

Social media platforms, search engines, and user-generated content sites faced constant legal threats. Most tech companies dared not oppose the legislation directly, fearing backlash from lawmakers.

Stark co-founded the Harvard Free Culture Group and helped coordinate campus protests. Her message: these bills would hold platforms liable for user content they couldn't monitor, thereby destroying the internet.

"This isn’t Google versus Hollywood," she explained, "it’s 15 million internet users versus Hollywood."

Wikipedia went dark for 24 hours. Reddit shut down. Protesters flooded congressional phone lines. Within days, lawmakers dropped the bills. SOPA and PIPA died in committee.

The movement taught Stark that sometimes you can’t defeat institutions through traditional channels—but you can make their preferred solutions politically impossible.

During law school, she also founded the Open Video Alliance and produced the first Open Video Conference. The inaugural event drew 9,000 participants, proving demand for alternatives to traditional media "gatekeepers." But organizing events and fighting bad legislation felt too reactive. After graduation, Stark held academic positions at Stanford and Yale, teaching how the internet reshapes society and economies. She studied digital rights and worked with policy groups to develop better frameworks around emerging technologies.

Policy solutions always lag behind technological change. By the time lawmakers understand a new technology well enough to regulate it properly, the technology has already evolved into something else.

What if you could build technology that resists bad regulation from the start?

The Bitcoin Battle

In 2015, the Bitcoin community was fighting for its future.

The "block size war" had been raging for months. Bitcoin could process only about seven transactions per second—far too little to compete with traditional payment networks. One faction wanted larger blocks to accommodate more transactions. Another wanted to keep blocks small to preserve decentralization.

The debate was existential. Would Bitcoin remain decentralized, or fall under control of mining companies and corporate interests?

Elizabeth Stark watched this struggle with interest. She had seen similar battles in internet governance, where technical decisions often carried political weight. But Bitcoin was different. There was no central authority to impose a solution. The community had to reach consensus through code and economic incentives.

As tensions rose, developers proposed an alternative: build a second-layer network atop Bitcoin capable of handling millions of transactions per second while preserving the base layer’s security.

This was the Lightning Network.

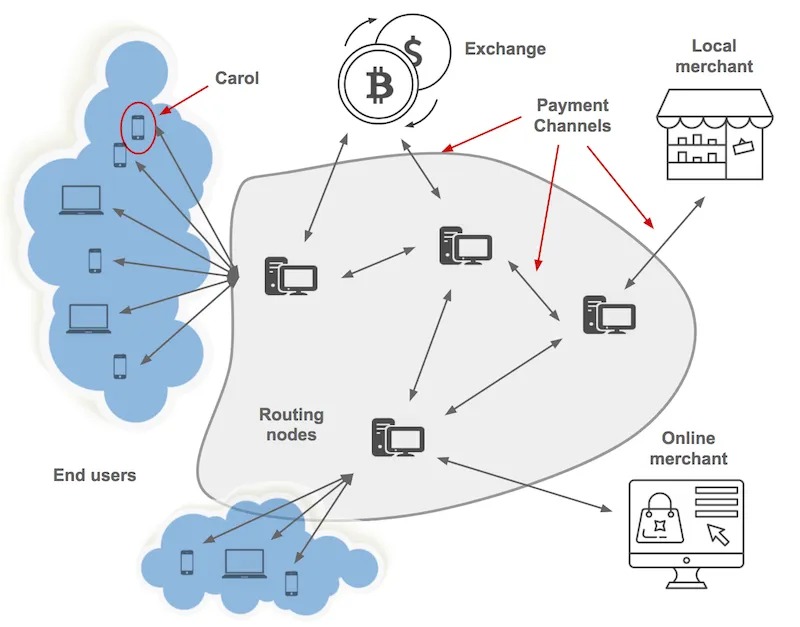

Instead of recording every transaction on the Bitcoin blockchain, users could open payment channels and settle multiple transactions off-chain. Only opening and closing channels required blockchain transactions.

These channels could interconnect. If Alice has a channel with Bob, and Bob with Carol, Alice can pay Carol via Bob. The network would form an interconnected system of payment channels, enabling instant, low-fee transactions.

Stark saw both potential and challenges. The Lightning Network was still theoretical. It required complex cryptographic protocols and hadn’t been tested at scale. Most Bitcoin users didn’t understand why a second-layer solution was needed.

In 2016, she co-founded Lightning Labs with programmer Olaoluwa Osuntokun. The timing was risky, but Stark’s activism had taught her that the best time to build alternatives is before everyone realizes they’re necessary.

Building Infrastructure

Lightning Labs released the first Lightning Network test version in 2018. The software was incomplete—channels frequently failed, liquidity management was confusing, and most wallets couldn’t integrate the technology correctly.

But it worked. Users could open channels, make instant payments, and close channels without waiting for blockchain confirmations. Early adopters were mostly developers who understood the technology’s potential.

Stark aimed to serve billions lacking reliable financial services. Her team focused on real-world problems users actually faced.

How to manage channel liquidity to prevent payment failures? Lightning Loop allowed users to move funds between channels and the blockchain without closing channels, solving some—but not all—liquidity issues.

How to create a liquidity market? Lightning Pool created a marketplace for buying and selling channel capacity, though adoption remained limited to advanced users.

How to run the Lightning Network on mobile devices without draining battery life? Neutrino enabled privacy-preserving light clients, but the technology remained too complex for mainstream use.

Each product addressed a specific infrastructure problem. Progress was slow; the Lightning Network remained difficult for non-technical users. Channel management demanded constant attention. Payments often failed because routing couldn’t find paths with sufficient liquidity.

But foundations were strengthening. Mainstream wallets began integrating Lightning. Payment processors started offering Lightning services. The network grew from dozens to thousands of nodes, though most capacity remained concentrated among a few large ones.

Critics pointed out that the Lightning Network’s hub-and-spoke topology wasn’t as decentralized as advertised. They questioned whether the technology could scale without being dominated by major payment processors. Stark acknowledged these concerns but argued the network was still early; better solutions would emerge as the technology matured.

Betting on Stablecoins

By 2022, stablecoin transaction volumes surged. Tether and USDC processed over $1 trillion annually—more than many traditional payment networks. But most stablecoins ran on Ethereum and other blockchains less secure than Bitcoin.

Stark saw an opportunity. Lightning Labs raised $70 million to develop what became Taproot Assets—a protocol for issuing and transferring stablecoins on Bitcoin. The technology leverages Bitcoin’s Taproot upgrade to embed asset data within regular transactions, making stablecoin transfers indistinguishable from ordinary Bitcoin payments.

These assets can move over the Lightning Network. Users can instantly send dollars, euros, or other assets while benefiting from Bitcoin’s security. Each stablecoin transaction routes through Bitcoin liquidity, potentially increasing demand for Bitcoin and generating fees for node operators.

"We want to bitcoinize the dollar," Stark explained—though it remains unclear whether people actually want their dollars bitcoinized.

Why? While the technology supports dollar-denominated stablecoins on Bitcoin, the vast majority of stablecoin users remain on Ethereum and other more mature ecosystems with deeper infrastructure, liquidity, and developer activity—making Bitcoin-based stablecoins a niche market.

Bitcoin purists sometimes question adding non-Bitcoin assets to Bitcoin, reflecting ideological hesitation or a preference for keeping Bitcoin as pure "digital gold" rather than a multi-asset settlement layer.

Users in emerging and inflation-prone markets need stablecoins for stability, but adoption on the Bitcoin Lightning Network must overcome complexity, liquidity, and usability hurdles compared to established stablecoin rails. The market is still determining product-market fit for stablecoins on Lightning, so mass "dollar bitcoinization" remains aspirational, not proven.

Yet, the trademark dispute forced "Taro" to become Taproot Assets—but development continued. By 2024, Lightning Labs had launched Taproot Assets and begun processing real stablecoin transactions. Bridging services moved USDT from Ethereum to the Bitcoin Lightning Network; users could send dollars for just a few cents.

But adoption remains limited. Most stablecoin users stay on the more developed Ethereum ecosystem. Bitcoin purists question whether introducing other assets to Bitcoin is necessary or desirable. The technology works—but product-market fit remains elusive.

The Network Effects Problem

Today, Lightning Labs operates critical Bitcoin infrastructure by developing and maintaining LND (Lightning Network Daemon). LND is the primary software implementation of the Lightning Network, powering most of Bitcoin’s second-layer payment channels. Yet Elizabeth Stark’s grand vision remains unproven. She envisions building a "financial internet"—a global financial system operating without government or corporate permission.

Theoretically, the comparison to internet protocols holds. Just as anyone can build websites and apps on internet protocols, anyone could build financial services on the Lightning protocol. The network would be open, interoperable, and censorship-resistant.

But networks are only valuable when people use them. The Lightning Network sees fastest adoption in countries with unstable currencies or unreliable banking systems—but even there, user counts number in the thousands, not millions. Remittance companies have experimented with Lightning, yet most business still relies on traditional channels.

Stark’s team is working on integrating AI for autonomous payments, improving privacy, and providing educational resources for developers. Each advancement is technically impressive, but mainstream adoption still feels distant.

"Bitcoin is a movement," Stark says. "Everyone here is building a new financial system."

The movement exists, but its impact on ordinary people remains limited. In theory, the Lightning Network can handle thousands of transactions per second; in practice, most people still use credit cards and bank transfers. Whether Bitcoin payments can become as natural as sending emails depends on solving long-standing usability issues.

But the Lightning Network remains far from Stark’s vision of being "as simple as sending an email." Managing channel liquidity is like running your own bank’s operations—you must constantly monitor balances on both ends of your payment channels, or transactions fail. Payment routing can break when paths lack sufficient liquidity, which happens more often than expected. Setting up Lightning still requires reading documentation and understanding concepts like "inbound capacity." Most people just want to click a button to transfer money—not become amateur liquidity managers.

Lightning Labs has invested $70 million into developing Taproot Assets, improving node software, and convincing developers to build Lightning applications. Taproot Assets aims to let stablecoins and other tokens flow through Lightning channels—which might matter only if people genuinely prefer sending stablecoins via Bitcoin infrastructure instead of existing stablecoin networks. They’re also trying to make LND software easier to use and educating developers on why they should care about Lightning. Whether these efforts will enable ordinary people to use Lightning for daily payments remains unknown.

The technology works. But "working" and "good enough for ordinary people" are two different things.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News