The wallet of U.S. stocks and crypto, perhaps he will have the final say in the future

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The wallet of U.S. stocks and crypto, perhaps he will have the final say in the future

After Powell, is it him?

By David, TechFlow

With nine months remaining until Powell's term ends, speculation over who will succeed him as Chair of the Federal Reserve has intensified.

The Fed Chair may hold the world's most powerful economic position. A single statement can trigger massive market volatility; a single decision can redirect trillions of dollars. Your mortgage rate, stock returns, and even fluctuations in crypto assets are all tied to decisions made from this seat.

So who is most likely to be the next chair? The markets are gradually offering their answer.

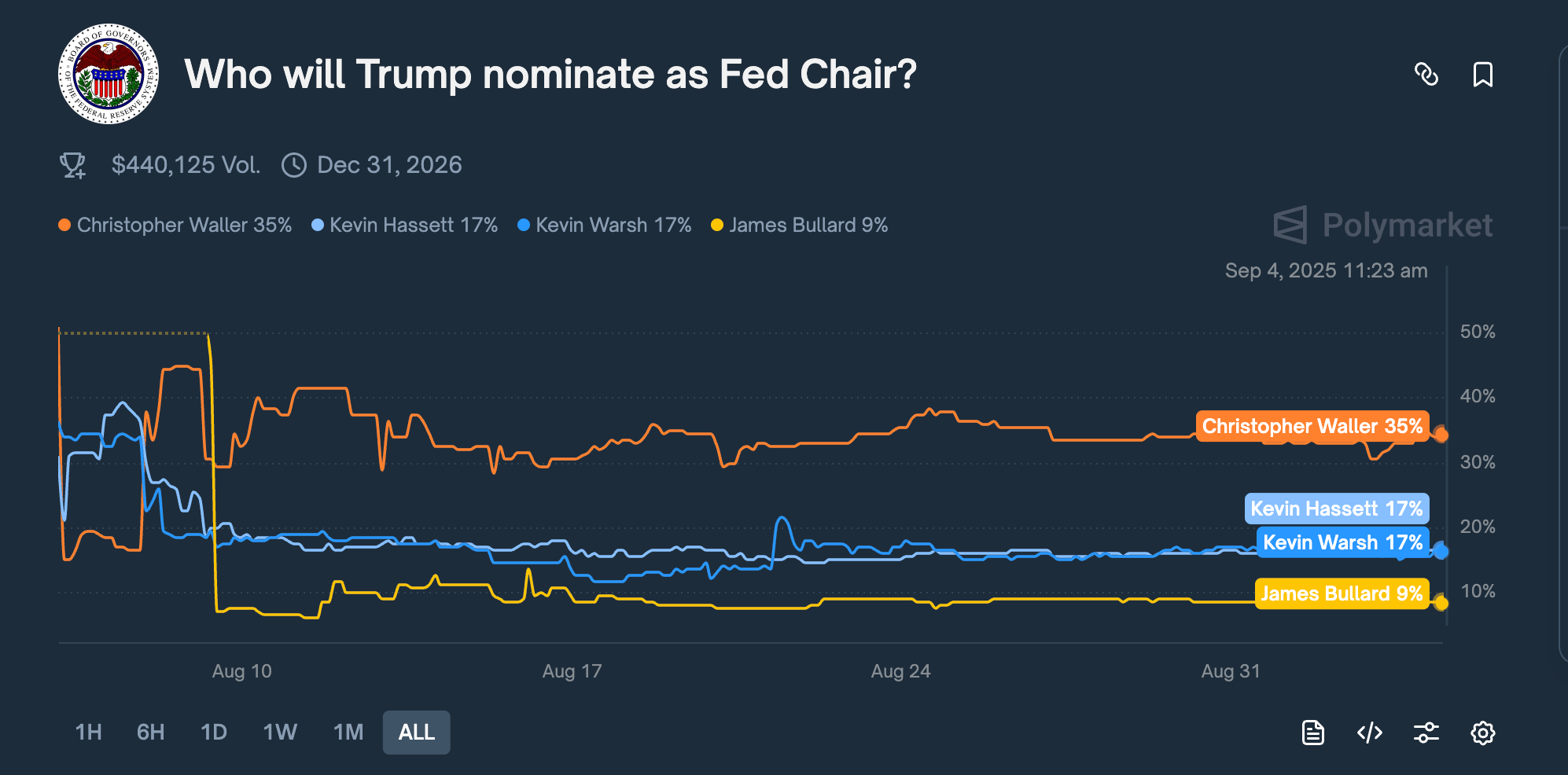

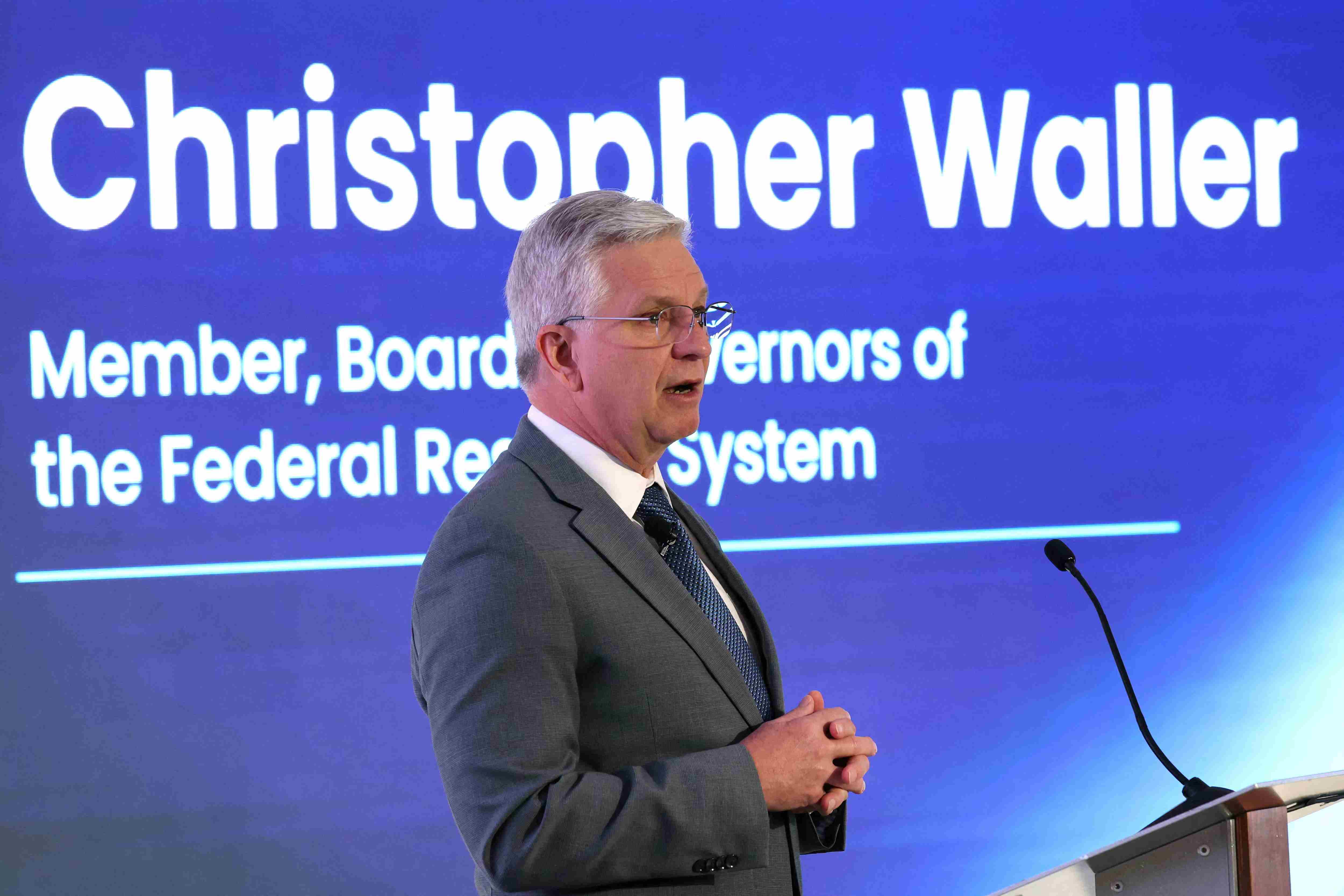

On August 7, on prediction market Kalshi, Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller’s odds surged from 16% the previous day to over 50%, surpassing all rivals for the first time. Although the odds have fluctuated since, Waller has maintained his lead.

According to the latest data, Polymarket shows Waller still leading with a 35% probability, ahead of other frontrunners Kevin Hassett and Kevin Warsh, both at 17%.

Why has the market suddenly warmed to this 65-year-old sitting Fed governor?

A recent report by Bloomberg may offer a clue: Trump’s advisory team sees Waller as “willing to make policy based on forecasts rather than current data” and possessing “deep understanding of the Fed system.”

More importantly, Waller was one of Trump’s 2020 appointees to the Fed Board. And on July 30 during the FOMC meeting, Waller did something particularly notable:

He joined fellow governor Michelle Bowman in voting against holding rates steady, arguing the Fed should cut rates by 25 basis points. This marks the first time since 1993 that two governors simultaneously opposed a decision to maintain interest rates.

What Trump needs now is a Fed chair who can push for rate cuts without being seen as a puppet of the White House. From this perspective, Waller appears to perfectly fit the bill.

Political Instinct: Timing Is Everything

To understand Waller, we must start with that dissenting vote.

First, some context: The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets eight times a year to set the U.S. benchmark interest rate—the main lever controlling the economy. This rate determines interbank lending costs, which ripple through all loan rates.

Participants vote collectively on rate changes. For decades, these votes were nearly always unanimous. In Fed culture, publicly casting a dissenting vote is seen as challenging the chair’s authority.

The FOMC meeting on July 30, 2025, was especially sensitive.

The Fed had held rates steady at 4.25%-4.5% for five consecutive meetings. Meanwhile, Trump had been relentlessly attacking Powell on Truth Social, calling him “too late” and “stupid,” demanding immediate rate cuts to stimulate the economy.

Just two weeks before the meeting, on July 17, Waller delivered a sharp speech at the Money Marketeers Association of New York University:

“I used to tell my new colleagues, a speech isn’t a murder mystery—telling the audience who the killer is, is telling them the point.”

The point of this speech, naturally, was that he believed the FOMC should cut rates by 25 basis points—and the “killer” was implicitly the Fed itself.

Public statements like this generally go against central bankers’ usual code of conduct. But this may have been a carefully chosen moment for political positioning.

By stating his views publicly in advance, Waller could frame his later dissenting vote at the formal FOMC meeting as the result of long-held professional judgment—not submission to political pressure.

When Waller and Bowman voted against holding rates steady on July 30, it was the first time since 1993 that two governors jointly dissented—a move bound to attract attention.

The market interpreted it as a sign of rational internal disagreement. But from Trump’s team’s perspective, this looked more like a deliberate signal of alignment.

Waller also voiced his take on current tariff policies: “Tariffs are a one-time increase in price levels and do not cause persistent inflation.” This became his most widely quoted line across media outlets.

In other words, the subtext is clear:

Trump’s tariffs will indeed raise prices—but only temporarily. Therefore, they shouldn’t prevent rate cuts. Clearly, Waller’s view neither criticizes Trump’s tariffs nor undermines the case for easing monetary policy.

Using economic theory to resolve a political dilemma, picking the right moment to express alignment with the president on rate cuts.

Betting Against the Former Treasury Secretary: Predicting a Soft Landing

If casting a dissenting vote revealed Waller’s political instincts, correctly forecasting the economy demonstrated his technical expertise.

Here’s the background.

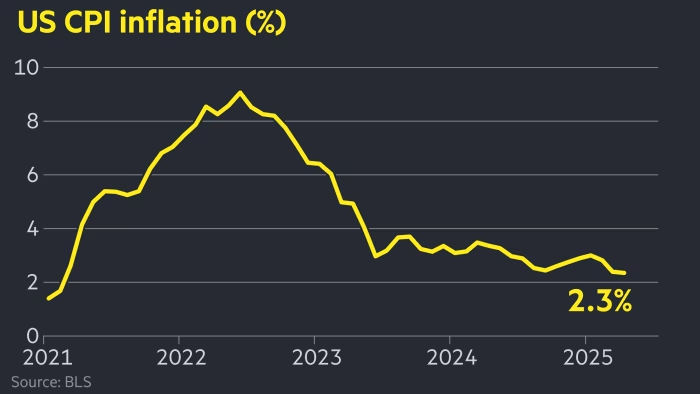

In June 2022, U.S. inflation hit 9.1%, the highest in 40 years. What does that mean?

If you saved $10,000 at the start of the year, by year-end its purchasing power would be down to $9,000. Gas prices doubled; eggs rose from $2 to $5.

The Fed faced a tough choice. To fight inflation, it needed to raise rates. Higher rates make borrowing costlier, discouraging business expansion and consumer loans for homes and cars, cooling the economy and bringing inflation down.

But there’s a risk: if the medicine is too strong, it causes recession. Historically, every major Fed rate hike has triggered an economic downturn.

At this point, an unusual public debate erupted among economists.

On one side were three heavyweight economists: former Clinton Treasury Secretary Summers, former IMF chief economist Blanchard, and Harvard economist Domash.

In July, they published research arguing the Fed couldn’t control inflation without causing a “painful” spike in unemployment. To bring inflation down, unemployment must rise—it’s an economic law, as immutable as physics.

Summers’ team calculated that cutting inflation from 9% to 2% would require unemployment to rise above 6%, meaning millions would lose jobs.

Waller disagreed.

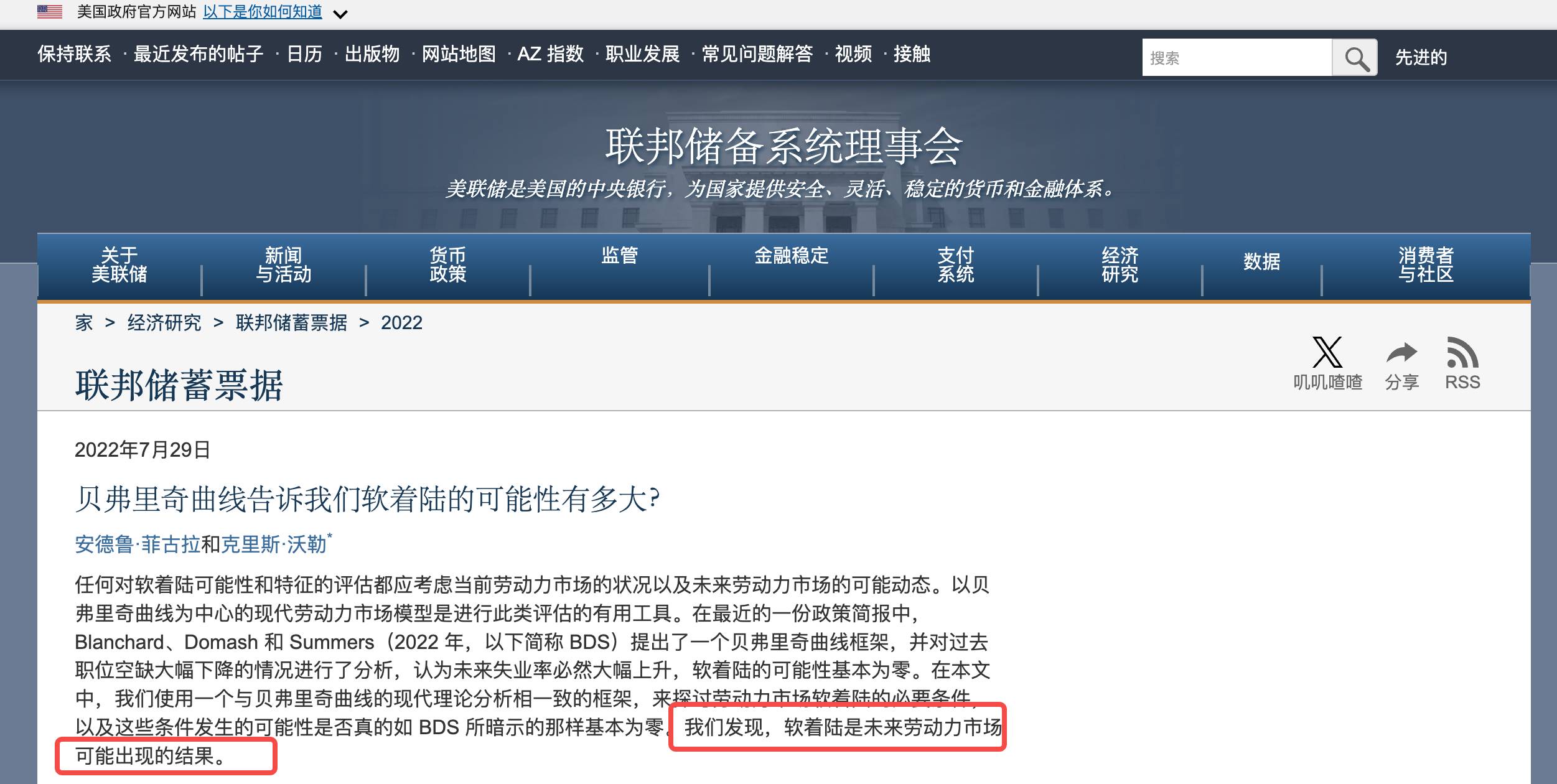

On July 29, he co-authored a paper with Fed economist Andrew Figura titled “What Does the Beveridge Curve Tell Us About the Likelihood of a Soft Landing?”, directly challenging Summers’ conclusion.

Waller’s core argument: this time is different because the pandemic caused unprecedented distortions in the labor market.

Many people retired early or left the workforce due to the pandemic. This inflated job vacancy numbers—not because the economy was overheating, but because fewer people were willing to work.

Their conclusion: a soft landing is a “plausible outcome,” with inflation returning to target while unemployment rises only slightly.

On August 1, Summers and Blanchard fired back, calling Waller’s paper “misleading, factually incorrect, and erroneous.”

Central bankers usually choose words carefully; academics typically show courtesy. But here, both sides were unusually confrontational, defending the validity of their economic theories.

The market naturally sided with Summers. After all, he was a former Treasury secretary, Blanchard a former IMF chief economist. Waller, by comparison, was just a Fed governor.

The following 18 months turned into a public test and high-stakes bet.

By late 2022, commodity prices began falling. In early 2023, supply chain pressures eased. The Fed did hike rates aggressively—from near zero to 5.5%.

Everyone waited for mass layoffs. But the outcome was surprising.

By the end of 2024, inflation fell below 3%, while unemployment remained at 3.9%. No recession, no large-scale job losses.

In September 2024, Waller and Figura updated their paper—adding an “s” to the title: from “Soft Landing” to “Soft Landings,” suggesting this wasn’t a fluke but a repeatable outcome.

Waller won the bet.

The academic clash proved Waller could challenge authority and make independent judgments. For Trump’s team, this mattered even more—they saw someone unafraid to defy consensus and believe in the resilience of the U.S. economy.

A Midwestern Scholar Who Dared to Enter Washington

Waller differs from most Fed officials in having a unique career path.

Born in 1959 in Nebraska City, Nebraska—a town of just 7,000—he spent his childhood in South Dakota and Minnesota, agricultural states far from the East Coast financial centers.

Fed Board seats are typically filled by a certain type: Ivy League graduates, Wall Street veterans, or Washington insiders. They often speak the same language and share similar worldviews.

Waller clearly doesn’t belong to that group.

His starting point was Bemidji State University, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in economics—a school in northern Minnesota so obscure you might never have heard of it, where winter temperatures plunge to -30°C.

Growing up in such an environment may have given him a clearer view of ordinary Americans—people in small towns taking out loans to buy homes and cars, worried about jobs and prices.

In 1985, Waller earned his PhD in economics from Washington State University, launching a long academic career.

He taught at Indiana University, then the University of Kentucky, and finally Notre Dame—spending 24 years in academia focused on monetary theory, one of the most abstract branches of economics.

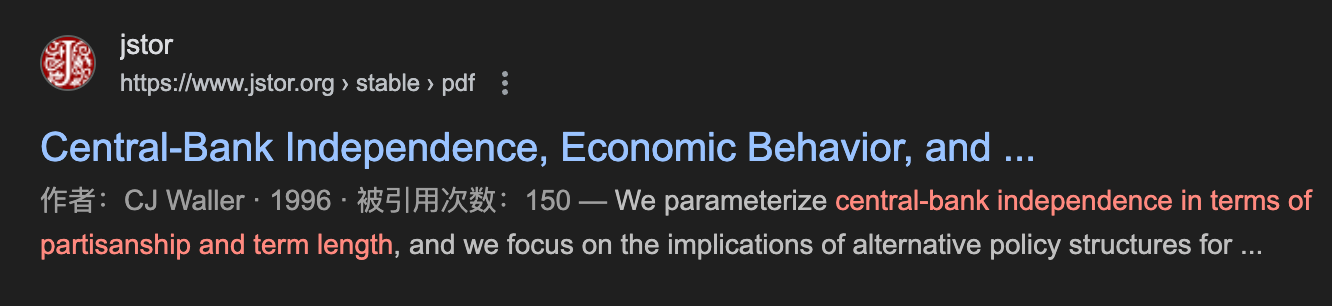

This kind of research rarely brings fame or TV appearances, but it can prove crucial in key moments. In 1996, Waller co-authored a paper “Central Bank Independence, Economic Behavior, and Optimal Term Length”.

The paper addressed a timely practical question: How long should a central bank governor’s term be?

The key finding: If the term is too short (e.g., 2 years), governors may yield to political pressure to secure reappointment. If too long (e.g., 14 years), they may become detached and inflexible.

Twenty-five years later, that theoretical paper became a real-world playbook.

In 2020, when Trump publicly attacked the Fed and demanded rate cuts, the newly appointed Waller faced a choice: full compliance or outright resistance?

He chose a third path: supporting rate cuts at times—like casting a dissenting vote in July 2025—but grounding those decisions in professional reasoning, not presidential demands.

This delicate balance—neither fully independent to the point of ignoring political reality, nor subservient enough to lose professional judgment—is precisely what he studied over two decades ago.

In other words, Waller navigates the Fed not by intuition on a tightrope, but guided by an academically tested theory of equilibrium.

Before joining the Fed, Waller also honed his skills in a “training ground.”

The Federal Reserve isn’t a single entity but consists of the Washington-based Board and 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks, each with its own research department and policy leanings.

In 2009, at age 50, Waller left academia to join the St. Louis Fed as Director of Research, serving for 11 years. He managed a research team of over 100, analyzing economic data, writing policy reports, and preparing for FOMC meetings.

What truly changed his trajectory was Trump’s 2019 nomination to the Fed Board.

The nomination itself was controversial. His confirmation process was rocky: Democratic senators questioned his independence as a Trump appointee, while Republican senators worried he was too academic and insufficiently “loyal.”

On December 3, 2020, the Senate narrowly confirmed him 48–47, one of the closest votes in recent memory. At 61, entering the Fed’s top decision-making body later than most, his age ironically became an advantage.

Most Fed governors follow a predictable path: elite schools → Wall Street/government → Fed. They enter the corridors of power in their 40s, with ample time to build connections and learn the rules.

Waller was different. Twenty-four years in academia, 11 in a regional Fed—only arriving in Washington at 61.

Compared to other governors, Waller carries fewer burdens, owes no favors to Wall Street. Having served at the St. Louis Fed, he knows the Fed isn’t monolithic—dissenting voices aren’t just tolerated, sometimes encouraged.

When Trump’s team evaluates potential successors to Powell, they may see exactly these traits:

A man old enough that he has nothing left to prove; independent-minded yet skilled at expressing views within the system.

Good News for Crypto?

If Waller becomes Fed Chair, what benefits might follow?

The market’s immediate reaction is that he’ll cut rates—after all, he cast a dissenting vote for a rate cut in July, and Trump has consistently pushed for lower rates.

But a closer look at his record reveals a more complex picture.

In 2019, when the economy was strong, Waller supported rate cuts. In 2022, amid soaring inflation, he backed aggressive hikes. In 2025, he shifted toward supporting cuts again…

His principle seems clear: loosen when needed, tighten when necessary. If he becomes chair, monetary policy may become more “flexible”—not rigidly following Trump’s dictates, but adjusting swiftly to economic conditions.

But Waller’s real distinction may lie not in traditional monetary policy, but in how he views emerging areas like crypto and stablecoins.

On August 20, when asked how the Fed should respond to financial innovation, Waller said, “There’s absolutely no need to worry about digital asset innovation.” At a stablecoin conference in California this February, he described stablecoins as “digital assets designed to maintain stable value relative to national currencies.”

Note his emphasis on their relationship to national currencies—not as alternatives outside the monetary system. This difference in perspective could lead to fundamental policy shifts.

Currently, the U.S. takes a defensive stance toward digital assets, worrying about money laundering, financial stability, and investor protection. Regulatory focus is on “risk control.”

Waller explicitly opposes central bank digital currency (CBDC), arguing “it’s unclear what market failure in the U.S. payment system a CBDC would solve.” Instead, he supports an alternative: allowing private-sector stablecoins to innovate and fulfill the role of a digital dollar.

Yet all these visions depend on one premise: that Waller can withstand pressure.

He hasn’t faced a true financial crisis test. When Lehman collapsed in 2008, he was teaching. When FTX went bankrupt in 2022, he had just joined the Fed and wasn’t a core decision-maker.

Moving from governor to chair isn’t just a promotion. Governors can express personal views; every word from the chair can shake markets.

When the stability of the entire financial system rests on your shoulders, “innovation” and “exploration” may become luxuries. Whether this is entirely good news for crypto remains uncertain.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News