A Preliminary Study on Singapore's Cryptocurrency Tax and Regulatory System (Part 1)

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

A Preliminary Study on Singapore's Cryptocurrency Tax and Regulatory System (Part 1)

This study will focus on the two main threads of basic tax systems and regulatory frameworks, illustrating the interaction between institutions and markets in Singapore's cryptocurrency ecosystem, clearly outlining the current state of Singapore's crypto industry for investors, and aiming to provide a reliable basis for business decisions.

Author: Carlton, FinTax

1. Introduction

Singapore, as a major global financial center, has long attracted global capital and innovation with its open market environment, robust legal system, and efficient regulatory framework. In recent years, as digital assets and blockchain technology have rapidly advanced, this city-state has gradually become a key hub for cryptocurrencies in the Asia-Pacific region. It hosts numerous startups and international trading platforms, while also drawing institutional investors, developers, and policymakers to explore the future of digital finance. Driven by diverse market demands and proactive policy support, Singapore's crypto ecosystem is steadily maturing.

According to the Independent Reserve Cryptocurrency Index (IRCI) Singapore 2025 report, cryptocurrency awareness in Singapore has reached an all-time high, with 94% of respondents aware of at least one type of crypto asset and 29% having previously owned crypto assets. Among them, 68% of crypto investors hold Bitcoin, and 46% have held or currently hold stablecoins, with usage rates for stablecoins in real-world payments and cross-border transfers reaching 53%. Additionally, 57% of crypto asset holders believe the industry will achieve mainstream adoption in the future, while 58% of the public call for clearer government regulation... Together, these figures depict a market with widespread awareness, diversified applications, and clear expectations regarding regulation.

Against this backdrop, understanding Singapore’s cryptocurrency tax and regulatory systems is not only essential for legal compliance but also critical for assessing market potential and risk landscape. This study focuses on two core pillars—taxation and regulation—to illustrate the interaction between institutional frameworks and market dynamics within Singapore’s crypto ecosystem, aiming to provide investors with a clear picture of the current state of the industry and reliable insights for business decision-making.

2. Regulatory Framework

Cryptocurrencies are often associated with risk. Unlike jurisdictions such as the United States, where individual states may impose unique crypto regulations, Singapore’s regulatory framework stands out for its clarity and balance. Although obtaining relevant licenses and qualifications can be challenging for many Web3 companies operating in Singapore, this very rigor helps significantly mitigate risks among local Web3 enterprises.

In Singapore, taxation and financial regulation of crypto assets are managed separately by the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) and the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), respectively.

Tax administration for cryptocurrencies is primarily handled by IRAS. As the national tax authority, IRAS formulates and implements policies related to income tax and goods and services tax (GST) concerning digital assets, covering tax obligations arising from holding, trading, paying, issuing, and other activities for both individuals and businesses. IRAS has issued several dedicated e-Tax Guides addressing income tax treatment of digital tokens and GST treatment of digital payment tokens, clearly defining tax classifications, taxable events, and principles for different token types (payment, utility, and security tokens). Furthermore, IRAS leads efforts to implement the Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework (CARF) domestically, playing a central role in cross-border tax information exchange.

MAS holds primary responsibility for financial regulation of cryptocurrencies. Functioning both as a central bank and as an integrated regulator for financial services and payments, MAS exerts significant influence over licensing, compliance, and risk management for crypto-related businesses. For instance, MAS’s licensing requirements for Digital Payment Token Service Providers (DPTSPs) and its regulatory framework for stablecoins indirectly shape tax treatment and compliance pathways for related operations.

3. Fundamental Study of Singapore’s Cryptocurrency Tax System

Singapore’s tax system is known for its simplicity and concentrated tax base. Its most notable feature is the absence of capital gains tax globally, along with the elimination of estate and gift taxes. This means that asset appreciation itself typically does not trigger a standalone tax event in Singapore; taxability depends instead on the nature and frequency of transactions. Combined with relatively low income tax rates, the system maintains fiscal stability while remaining highly accommodating to capital flows and innovative activities.

Under this framework, Singapore’s taxation of crypto assets is relatively focused, centered mainly on two key taxes: income tax and goods and services tax (GST). The former targets income derived from frequent or commercially oriented crypto transactions, while the latter governs indirect taxation when digital payment tokens are used in exchanges for goods and services. Other taxes, such as withholding tax or employment income tax, apply only under specific transaction structures or payment scenarios.

(i) Income Tax

Singapore follows a territorial source principle for income tax, meaning only income sourced in Singapore or remitted into Singapore from overseas is taxed. Personal income tax uses a progressive rate structure, ranging from 0% to 22% for residents (rising to 24% starting from the 2024 assessment year), while non-residents are generally taxed at a flat rate of 15% or the higher resident rate, whichever applies. The corporate income tax rate is uniformly set at 17%, with incentives including tax exemptions for startups and sector-specific relief measures.

On April 17, 2020, IRAS released "Income Tax Treatment of Digital Tokens," providing guidance on the income tax implications of transactions involving digital tokens.

The guide classifies digital tokens into three categories: payment tokens, utility tokens, and security tokens.

The guide covers the following five types of transactions:

i. Receiving digital tokens as payment for goods and services;

ii. Receiving digital tokens as employment compensation;

iii. Using digital tokens to pay for goods and services;

iv. Buying or selling digital tokens; or

v. Issuing digital tokens through an initial coin offering (ICO).

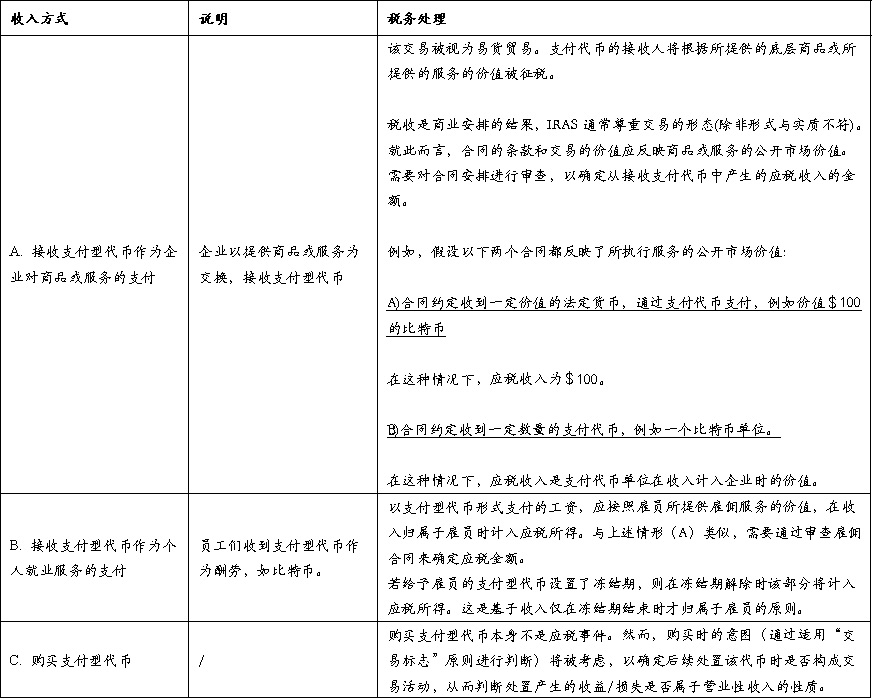

1. Tax Treatment of Payment Tokens

Synonymous with cryptocurrencies, payment tokens serve no function beyond payment.

Although payment tokens function as a means of payment, they are not issued by governments and therefore lack legal tender status. For tax purposes, IRAS treats payment tokens as intangible property representing a bundle of rights and obligations. Transactions involving goods or services paid for using payment tokens are treated as barter trade, requiring valuation of the goods or services transferred at the time of transaction.

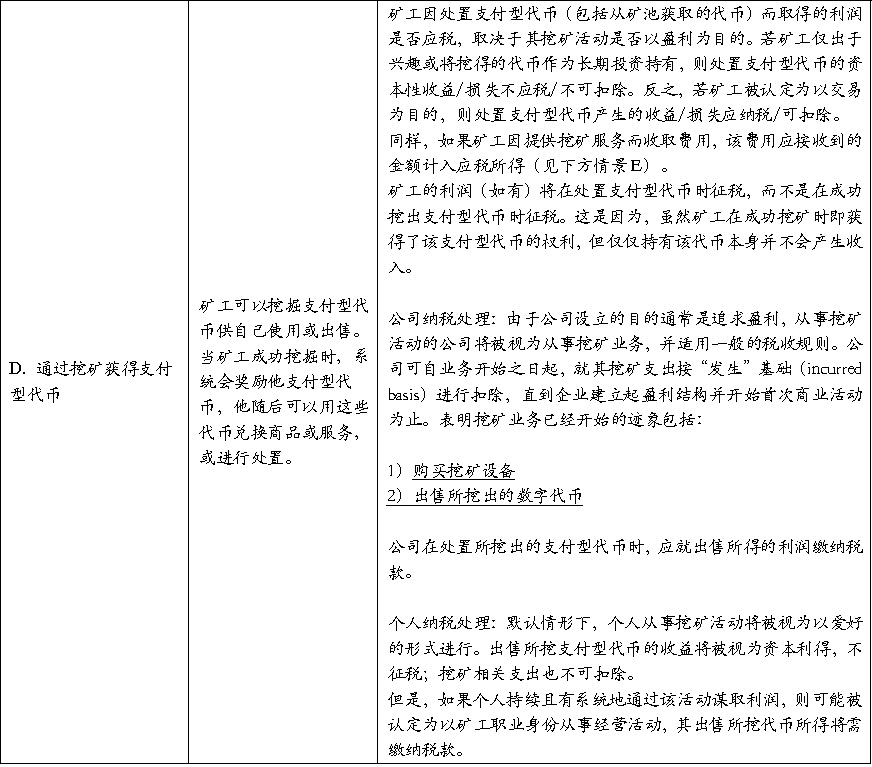

Table 1: Classification and Tax Treatment of Payment Tokens under Income Tax

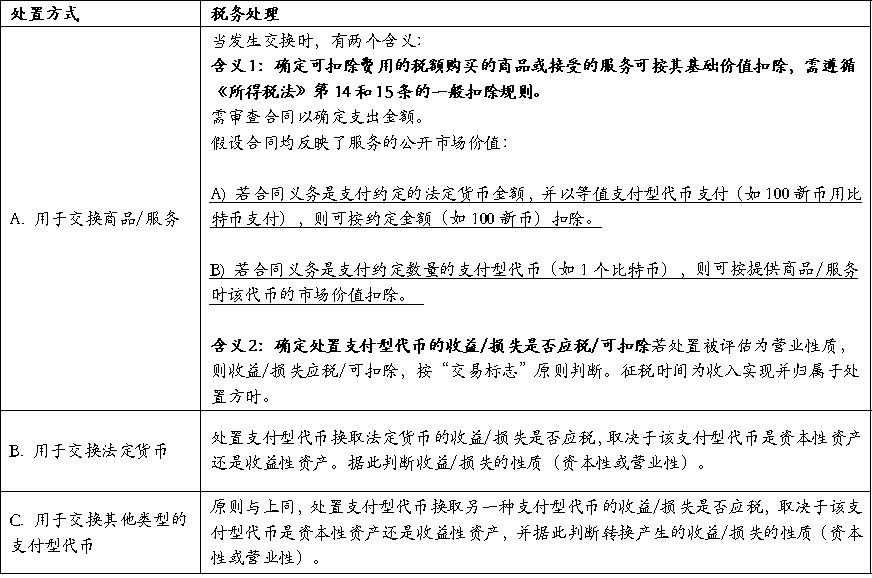

Table 2: Tax Treatment under Different Disposal Methods

2. Tax Treatment of Utility Tokens

Utility tokens grant holders explicit or implicit rights to use or benefit from specific goods or services, and can be exchanged for those goods or services.

They take various forms—for example, vouchers (granting holders the right to receive services from the ICO issuer in the future) or access keys (granting platform access). When an individual ("user") acquires a utility token for future redemption of goods or services, the expenditure incurred is treated as a prepayment. Under tax deduction rules, deductions may be claimed when the token is actually used to redeem the goods or services.

Tax treatment of utility tokens issued during an ICO will be explained in Section IV on ICO tax treatment.

3. Tax Treatment of Security Tokens

Security tokens confer partial ownership or rights over an underlying asset, typically carrying explicit or implied control rights or economic benefits. Most issued security tokens are currently accounted for as debt or equity instruments. However, since security tokens are essentially tokenized versions of traditional securities, they may also take other forms such as units in a Collective Investment Scheme (CIS). The nature of a security token depends on the rights and obligations attached, which determines the character of returns received—such as interest, dividends, or other distributions—that must be reported and taxed accordingly by the holder.

When a holder disposes of a security token, the tax treatment of the gain or loss depends on whether the token is classified as a capital asset or revenue asset. Gains or losses are then treated as either capital or revenue in nature.

Security tokens are subject to relatively relaxed tax policies similar to other securities in Singapore—no tax is imposed on security tokens held as capital assets. Instead, income such as dividends, if categorized as revenue-generating, will be taxed based on the issuer of the security token.

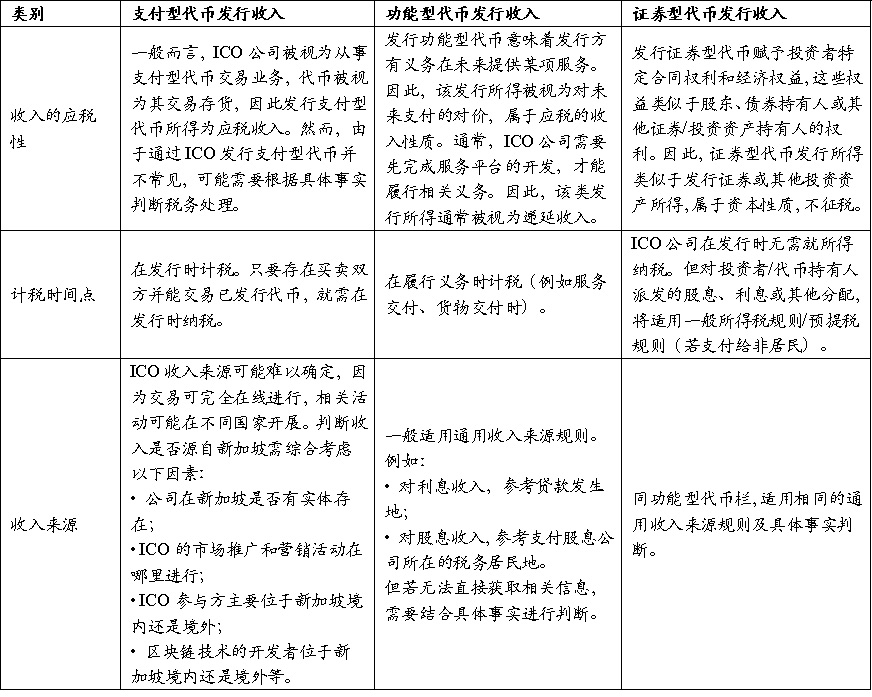

4. Tax Treatment of ICOs

An ICO, or Initial Coin Offering, involves issuing a new token, typically in exchange for other payment tokens or, in some cases, fiat currency. ICOs are commonly used by issuers to raise funds or to provide access to existing or future goods and services.

The taxability of funds raised through an ICO depends on the rights and functionalities attached to the tokens issued to investors:

-

Proceeds from issuing payment tokens are taxable depending on specific facts and circumstances;

-

Proceeds from issuing utility tokens are generally treated as deferred revenue;

-

Proceeds from issuing security tokens are akin to proceeds from issuing securities or other investment assets/instruments and are considered capital receipts, hence non-taxable.

For security tokens that pay interest, dividends, or other distributions, the deductibility of such payments by the issuer follows Sections 14 and 15 of the Income Tax Act.

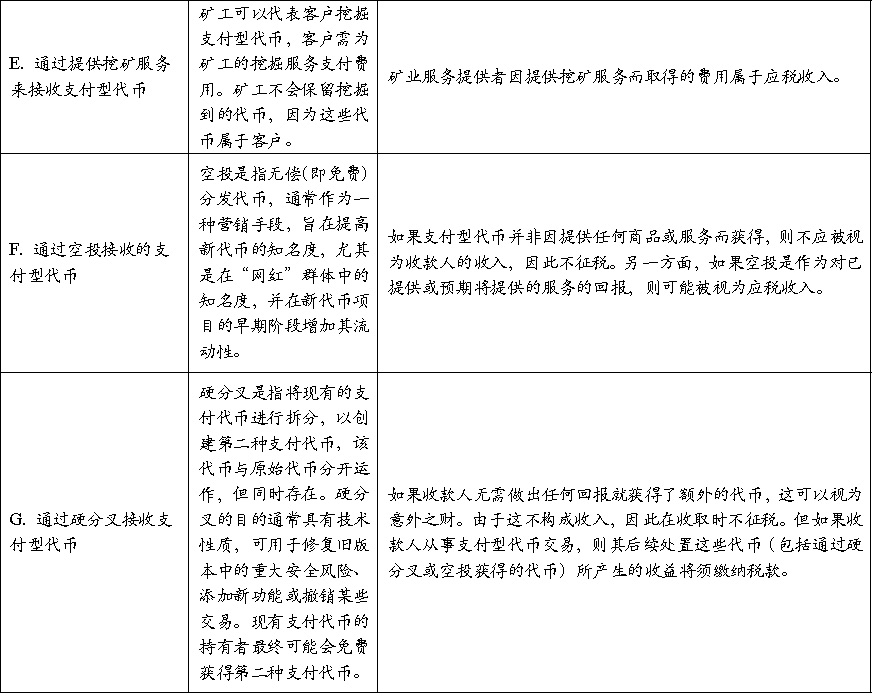

Refer to Table 3 for details.

Additional special situations may arise:

-

Failed ICO: If a company issues utility tokens via ICO and uses the raised funds to develop a platform or service but ultimately fails to deliver, the tax treatment depends on how the funds were used. If funds are refunded to investors, the company does not need to pay tax on the refunded amount. If not refunded, the nature of the transaction—capital or revenue—must be assessed based on factors such as the company’s main business, purpose of token issuance, and contractual obligations.

-

Preliminary expenses: Reasonable business expenses incurred before formal operations commence, such as those related to an ICO, may be claimed under current preliminary expense deduction rules. Under Section 14U of the Income Tax Act, qualifying expenses may be deducted in the pre-operational base period, and unused losses may be carried forward or utilized through Group Relief. This provision helps reduce tax burdens for startups.

-

Founder tokens: An ICO company may reserve tokens for founding developers to recognize their contributions to token design and implementation. Such "founder tokens," if granted as compensation for services, constitute taxable income and are taxed when the founder obtains control. If subject to lock-up or vesting periods, taxation occurs upon expiry at the fair market value then. If not received in exchange for services, they are not treated as taxable income.

Note: IRAS explicitly requires taxpayers to maintain complete records of all digital token transactions and to produce them when required. These records should include transaction dates, number of tokens received or sold, token value and exchange rates at the time of transaction, purpose of transaction, customer or supplier information (for buy/sell transactions), ICO details, and receipts or invoices for business expenses. These documents serve not only as the basis for tax filing but also as crucial evidence for audit defense and compliance assurance.

Table 3: Taxability of ICOs Based on Token Type

(ii) GST – Goods and Services Tax

Goods and Services Tax (GST) has been Singapore’s primary indirect tax since 1994. Broadly categorized as a consumption tax, it is levied on final consumption and operates fundamentally as a value-added tax (VAT), applied at a standard rate to most supplies of goods and services and imported goods. As of 2024, the standard GST rate is 9%. Businesses collect and remit GST, which applies to domestic transactions and cross-border digital services, while certain financial services, exports, and specific international services qualify for exemption or zero-rating.

On August 3, 2022, IRAS issued an updated version of "GST: Digital Payment Tokens" (originally published November 19, 2019), outlining the GST treatment of digital tokens and cryptocurrencies (referred to as digital payment tokens, or DPTs).

The key change introduced was the GST exemption for supplies of qualifying digital payment tokens (DPTs) effective January 1, 2020, aimed at preventing double taxation during both purchase and use of tokens. This adjustment significantly reduced tax friction in crypto payments and trading, enhancing Singapore’s competitiveness as a crypto-friendly jurisdiction. However, this exemption applies only to tokens meeting the DPT definition and does not affect normal taxation of intermediary fees, platform charges, and other taxable components.

The guide strictly defines DPTs and clarifies which tokens do not qualify for exemption (e.g., utility tokens, security tokens, closed-loop virtual currencies). It further distinguishes GST treatment across different token types and transaction stages such as trading, exchange, and payment. For example, buying, exchanging, or using compliant DPTs is exempt from GST, but services like platform operation, wallet custody, and payment intermediation remain taxable supplies under GST. Through this dual approach—based on asset attributes and business activity type—Singapore minimizes tax barriers to crypto transactions while preserving fairness in the tax system.

1. Defining Digital Payment Tokens

The guide defines a digital payment token (DPT) as a digital representation of value possessing all of the following characteristics:

(a) Represented in units;

(b) Designed to be fungible;

(c) Not denominated in any currency and not pegged to any currency by the issuer;

(d) Capable of being transferred, stored, or traded electronically;

(e) Intended to be, or is, accepted by the public or a segment of the public as a medium of exchange, without significant restrictions when used as consideration.

However, digital payment tokens do not include:

(f) Legal tender;

(g) Any supply that would be regarded as an exempt supply under Part I of the Fourth Schedule to the GST Act, solely because it meets criteria (a) to (e), unless the supply itself qualifies as a DPT;

(h) Any item that grants the right to receive or direct specific individuals or groups to provide goods or services and ceases to function as a medium of exchange once that right is exercised.

IRAS lists typical DPTs including Bitcoin, Ether, Litecoin, Dash, Monero, Ripple, and Zcash—all sharing core traits such as fungibility, non-pegging to fiat currencies, electronic transferability, and acceptance as public mediums of exchange. Additionally, tokens like IdealCoin, usable both within a specific smart contract framework and freely outside it, and StoreX, which remains circulatable as payment even after partial rights have been exercised, also meet the DPT definition.

In contrast, items not considered DPTs include stablecoins (due to their pegging to fiat currencies, violating fungibility and non-pegging requirements), virtual collectibles like CryptoKitties (non-fungible), game credits or virtual currencies restricted to specific environments, and loyalty points or rewards issued by retailers or platforms that can only be redeemed for specific goods or services—none of which function as broad public exchange media.

Some cases resemble DPTs at first glance but are excluded under certain conditions. For example, StoreY token was initially designed solely for purchasing distributed file storage services, but after exercising that specific right, it loses its function as a medium of exchange and thus no longer qualifies as a DPT.

For more detailed rules, characteristics, and illustrative examples, refer to Section 5 of the guide (particularly paragraphs 5.2–5.13 and accompanying examples).

2. General Transaction Rules for Digital Payment Tokens

When a DPT is used to pay for goods or services (excluding conversion into fiat currency or another DPT), the act of payment itself is not considered a "supply" and therefore not subject to GST. The payer does not incur GST when using DPTs, but if the recipient is GST-registered, they must account for output tax on the supplied goods or services, unless the supply is exempt, zero-rated, or outside the scope of GST. For example, if GST-registered Company A purchases software using Bitcoin, A does not pay GST on the Bitcoin transferred, but Seller Company B, if GST-registered, must charge GST on the software supply.

Second, exchanges between DPTs and fiat currencies, or between one DPT and another, are treated as exempt supplies and are not subject to GST. However, businesses must still report these transactions as exempt supplies in their GST filings and disclose any net realized gains or losses. For example, if Company C exchanges Bitcoin for Ether, neither party pays GST, but the transaction must be recorded as an exempt supply in their reports.

Additionally, if a GST-registered company issues DPTs through an ICO in exchange for fiat currency, the proceeds are also treated as an exempt supply and must be declared as such in the GST return. For example, if Company E issues DPTs and sells them to the public for Singapore dollars, the SGD proceeds are reported as exempt supply income.

Finally, loans, advances, or credit arrangements involving DPTs are also considered exempt supplies. Interest income generated from such arrangements is not subject to GST but must be reported as exempt income in GST filings. For example, if Company F lends DPTs and earns interest, the interest is listed as an exempt supply in the GST return.

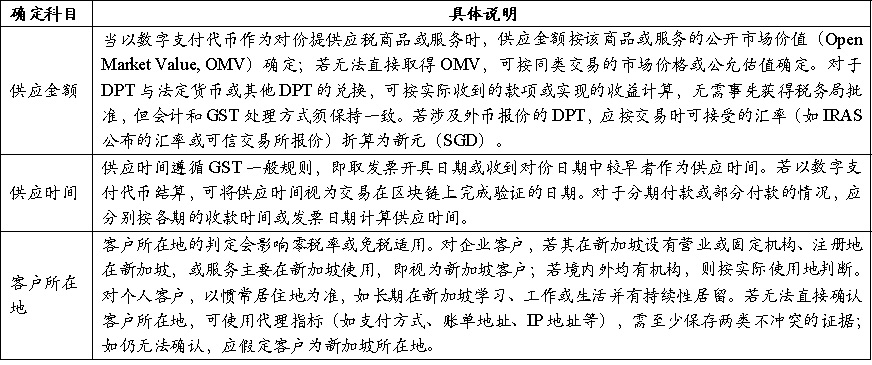

Table 4 outlines the specific rules for determining supply amount, timing of supply, and customer location in transactions involving digital payment tokens.

Table 4: Determination of Accounting Elements

3. Special Business Scenarios

(1) Mining

In general mining activities, miners provide computational power or validation services to the blockchain network but have no direct relationship with the parties involved in the transactions being validated, and the entity distributing block rewards or miner fees is unidentifiable. Therefore, receiving digital payment tokens from mining (e.g., block rewards) does not constitute a "supply" under GST and is not subject to GST.

However, if a miner provides compensated services to identifiable counterparties (e.g., charging commissions, transaction fees, or rental fees for computing power), this constitutes a taxable supply of services. If the miner is GST-registered, standard GST rates apply unless zero-rating conditions are met. If the location of the counterparty cannot be reasonably determined, standard GST rates apply.

Subsequent disposal of mined tokens: From January 1, 2020, selling or transferring mined digital payment tokens to customers in Singapore is an exempt supply. If a miner uses mined tokens to purchase goods or services, this is not treated as a "supply of tokens," so no GST is charged on the token portion (the supplier of goods/services still accounts for GST under normal rules).

(2) Intermediation

Services provided by intermediaries related to digital payment tokens remain taxable supplies, even if they involve token transactions. Whether a GST-registered intermediary must report token sales in its GST filing depends on whether it acts as a "principal" or "agent" in the transaction. If acting as a principal and selling tokens, the sale must be reported as its own supply subject to GST. If acting as an agent facilitating a client’s token sale, the sale amount should not be included in its own supply; only fees or spreads earned should be reported as taxable supplies (unless eligible for zero-rating). Institutions must self-assess their role based on indicators such as contractual liability, risk assumption, payment obligations, pricing authority, and token ownership.

(3) Input Tax Credit and Reverse Charge Treatment

Businesses may claim input tax credits only for expenses incurred in making taxable supplies. Expenses related to exempt supplies (e.g., exchanging digital payment tokens for fiat currency or other tokens) are not eligible for credit. If an expense relates to both taxable and exempt supplies, or to general business operations, credit must be apportioned accordingly. Businesses engaged in both taxable and exempt supplies (e.g., partially involved in DPT exchanges) must allocate input tax credits similarly to other partially exempt entities, unless the de minimis rule applies. In certain cases, DPT supplies may be treated as incidental exempt supplies. Finally, as partially exempt businesses, they may still bear reverse charge obligations for services or low-value goods received from overseas suppliers and should follow IRAS guidelines accordingly.

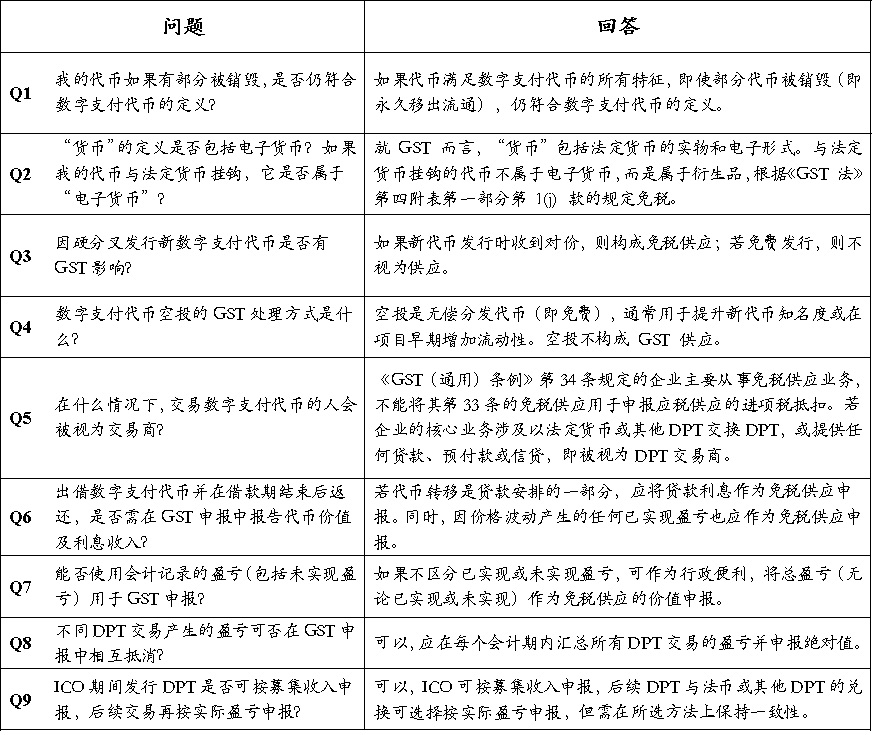

4. Common Questions

Table 5: Common Q&A

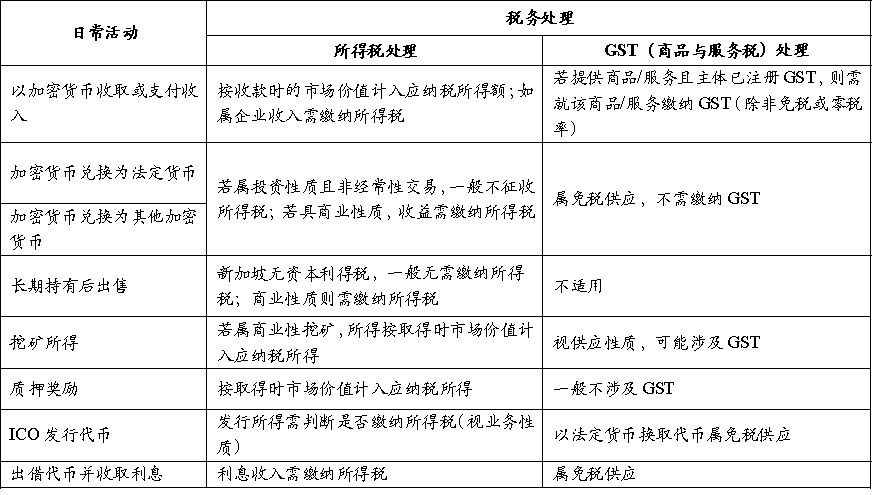

(iii) Classification by Usage Activities

Table 6: Taxability Classification by Daily Use Activities

(iv) Other Taxes

Globally, most countries classify cryptocurrencies as non-legal tender, so the main taxes involved are typically income tax, VAT, or consumption tax. The previous sections have comprehensively covered the primary tax treatment rules for cryptocurrencies in Singapore regarding everyday holding and usage. In comparison, other taxes have minimal relevance to daily crypto applications and will not be further discussed here.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News