Global Regulatory Similarities and Differences: Interpreting Four Bottom Lines and Three Key Divisions in the Crypto World

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Global Regulatory Similarities and Differences: Interpreting Four Bottom Lines and Three Key Divisions in the Crypto World

This article aims to provide institutional crypto asset players and compliance researchers with detailed information to help them understand the regulatory "red lines," minimum requirements, and differences across jurisdictions, thereby better managing compliance risks in cross-border operations.

Author: Yang Huiping (Northwest University of Political Science and Law)

01 Introduction

The cross-border liquidity of blockchain and crypto assets presents regulators worldwide with the challenge of balancing financial innovation against systemic risk. In this context, different jurisdictions are gradually outlining several non-negotiable "regulatory red lines" to govern public chain asset transactions and protect investor rights. For example, anti-money laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) requirements have almost become global consensus, with major jurisdictions generally incorporating virtual asset service providers (VASPs) into their AML legal frameworks[1]. Similarly, the independent custody and segregation of customer assets by trading platforms—ensuring that customer assets are not exposed to third-party creditors in the event of bankruptcy—is also regarded as a regulatory baseline requirement. Additionally, preventing market manipulation, curbing insider trading, and avoiding conflicts of interest between exchanges and affiliated parties have become common goals among regulators globally for maintaining market integrity and investor confidence[2][3].

Despite regulatory convergence in these key areas, significant divergence remains across jurisdictions on certain emerging issues. Stablecoin regulation is a typical case: some countries restrict stablecoin issuance to licensed banks and impose strict reserve requirements, while others remain in the legislative exploration phase[4][5]. Regarding crypto derivatives, a few jurisdictions (e.g., the UK) directly ban retail sales of such high-risk products[6], whereas others regulate trading through licensing systems and leverage limits. The legal status of privacy coins (anonymous cryptocurrencies) also varies widely: some nations explicitly prohibit exchanges from supporting privacy coin trading, while other regions have not legislated outright bans but indirectly suppress their circulation through stringent compliance controls[7]. Moreover, approaches to regulating real-world asset tokenization (RWA) and decentralized finance (DeFi) differ significantly: some jurisdictions actively establish sandbox trials and specialized regulations to bring such innovations under supervision, while others prefer to incorporate them into existing securities or financial regulatory frameworks.

To systematically analyze these convergences and divergences, this article selects representative jurisdictions in the United States, the European Union/United Kingdom, and East Asia for a cross-jurisdictional comparison of regulatory systems. Chapters Two through Five focus respectively on specific topics of regulatory red line consensus and institutional divergence, clarifying regulatory provisions across jurisdictions by citing actual regulation numbers, official documents issued by regulators, and notable institutional practices or cases[2][8]. Chapter Six summarizes similarities and differences in regulatory experiences across jurisdictions and discusses the implications and impacts of this regulatory landscape on the global crypto asset market. The concluding section offers reflections on future international regulatory coordination and industry compliance development.

Through this research, this article aims to provide detailed informational references for crypto asset institutions and compliance researchers, helping them understand the minimum thresholds and differences in regulatory “red lines” across jurisdictions, thereby better managing compliance risks in cross-border operations. It also offers policymakers a comparative perspective to explore potential pathways toward advancing regulatory coordination at the global level.

02 Regulatory Red Line Consensus: Fund Compliance and Asset Security

This chapter explores the two most consistently enforced global regulatory baselines: anti-money laundering (KYC/AML) and client asset segregation. While overall directions align, notable differences exist in specific implementation details.

2.1 Global Benchmark for Customer Identification and Anti-Money Laundering (KYC/AML)

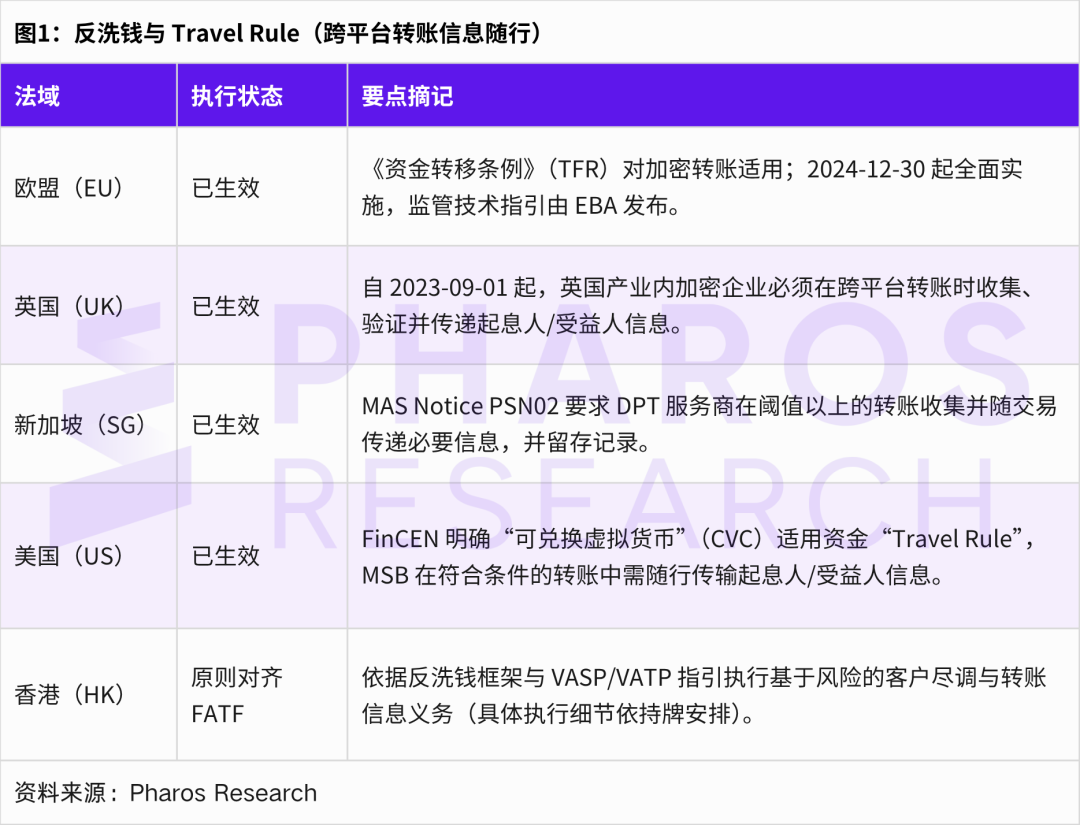

Since 2018, the extension of anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CFT) requirements to the crypto asset sector has become a global regulatory consensus. At the international level, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) revised Recommendation 15 in 2019, bringing virtual asset service providers (VASPs) under AML/CFT obligations equivalent in rigor to traditional financial institutions[1]. FATF also introduced the "Travel Rule," requiring VASPs to collect and transmit identity information of both senders and recipients during large-value crypto transactions[13]. This global standard has served as a benchmark for domestic legislation worldwide. As of 2025, the vast majority of major jurisdictions have incorporated VASPs into their national AML regulatory systems, establishing KYC procedures and suspicious transaction reporting mechanisms. According to the latest FATF report, 99 jurisdictions globally have enacted or advanced legislation to implement the Travel Rule, enhancing transparency in cross-border virtual asset transactions[14].

In the United States, AML obligations are primarily established under the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA, 1970) and its implementing regulations. The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), under the Treasury Department, has since 2013 clearly determined that most cryptocurrency exchanges fall within the definition of "money services businesses" (MSBs), mandating registration with FinCEN and compliance with BSA requirements[2]. Specific obligations include: implementing written Customer Identification Programs (CIP), collecting and verifying basic personal information such as name, address, and ID number; conducting Customer Due Diligence (CDD), identifying beneficial owners of corporate clients and understanding the purpose of transactions[15]; maintaining transaction records, and reporting suspicious activities (SARs) to authorities. Furthermore, the U.S. 2021 Infrastructure Act added tax reporting obligations for crypto transactions, and there are ongoing considerations to legislate enhanced information collection for non-custodial wallet transactions. On enforcement, U.S. authorities have repeatedly brought lawsuits and penalties against crypto firms violating AML rules: for instance, the prominent derivatives exchange BitMEX was deemed a "money laundering platform" for failing to implement KYC/AML controls, resulting in its founders pleading guilty to BSA violations and paying a $100 million fine[16][17]; another case involved a former Coinbase employee criminally charged with "bypassing KYC regulations for profit" via insider trading, highlighting regulators' intensified efforts against money laundering and fraud in the crypto industry.

The EU began including cryptocurrency exchanges and custodial wallet providers under AML supervision with the adoption of the Fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (5AMLD) in 2018, mandating licensing and KYC/AML compliance[18]. Member states subsequently revised domestic laws (such as Germany’s Anti-Money Laundering Act and France’s Monetary and Financial Code) to enforce identity verification and suspicious activity reporting for crypto service providers. In 2023, the EU formally adopted the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA, Regulation (EU)2023/1114), establishing a unified authorization regime for crypto-asset service providers (CASP)[19]. While MiCA primarily focuses on market conduct and investor protection, parallel developments include the 2024 agreement on the Anti-Money Laundering Regulation (AMLR) and the Sixth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (6AMLD) amendments, which impose higher due diligence and beneficial ownership identification requirements on obligated entities including CASPs[20]. Additionally, the EU plans to establish a dedicated Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA) to strengthen cross-border supervisory coordination. This means every crypto exchange operating within the EU must implement rigorous KYC procedures, continuously monitor customer transactions, and cooperate with law enforcement to combat money laundering, or face penalties including license revocation and substantial fines.

Asian financial centers have likewise followed international standards, establishing AML institutional frameworks for crypto assets. Regulators in Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, and other Asian jurisdictions emphasize that whether centralized exchanges or other types of VASPs, all must establish comprehensive AML compliance mechanisms and must not become conduits for money laundering or illicit fund flows.

Hong Kong amended its Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance (AMLO) in 2022, implementing a mandatory licensing regime for virtual asset service providers (VASPs) effective June 2023[21]. Under this ordinance and SFC guidance, platforms must strictly enforce measures such as customer identification, risk assessment, transaction monitoring, and periodic reviews, and comply with Travel Rule requirements by promptly transmitting customer and transaction information to counterparties[21].

Singapore brought digital payment token service providers under regulation via the 2019 Payment Services Act (PSA), with the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) issuing Notices (PSN02) detailing AML/CFT requirements, including applying the Travel Rule to virtual asset transfers exceeding 1,500 SGD and imposing enhanced due diligence on non-custodial wallet transactions[22].

Japan revised its Funds Settlement Act and Act on Prevention of Transfer of Criminal Proceeds (POTA) as early as 2017, requiring crypto asset exchange operators to register with the Financial Services Agency (FSA) and fulfill KYC and anti-money laundering obligations[23]. Japanese law mandates verification of customers’ names, addresses, and other details upon account opening, transaction monitoring, and additional scrutiny for transactions exceeding certain thresholds (e.g., 100,000 JPY)[23]. Notably, Japan is one of the proactive supporters of the Travel Rule, having incorporated it into domestic law, requiring transmission of sender and recipient information for virtual asset transfers exceeding 100,000 JPY[24].

From the above comparisons, it is evident that KYC/AML regulation has become a foundational "bottom-line" consensus in the global crypto asset trading domain: although legislative techniques and enforcement intensities vary slightly across jurisdictions, all recognize that strengthening customer identity verification and transaction transparency is essential to safeguarding the financial system from criminal abuse[1]. This consensus has created a de facto uniform compliance threshold for cross-border crypto operations—global institutions must meet KYC standards across jurisdictions and cooperate with suspicious funds monitoring, or they will struggle to obtain operational licenses. However, differences in enforcement intensity and specific rules persist (e.g., the U.S. pursuing criminal liability for violators, the EU emphasizing harmonized regulation, and Asian regions focusing on licensing oversight), requiring enterprises to carefully consider local regulatory nuances when formulating global compliance strategies.

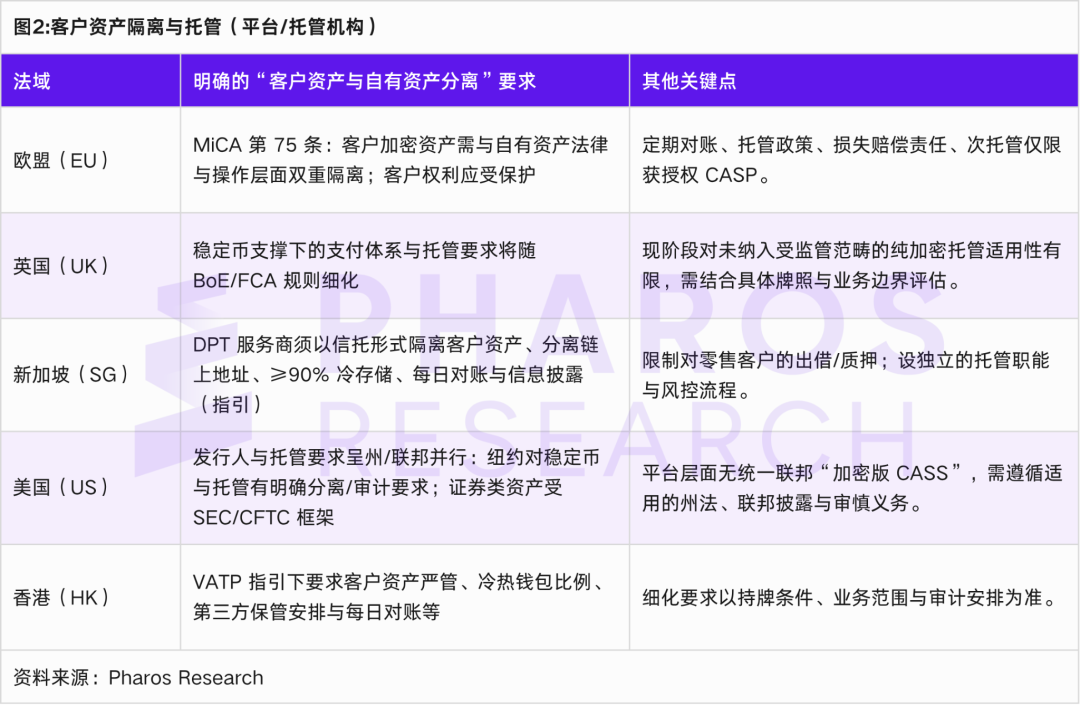

2.2 Independent Custody and Segregation of Client Assets

Client asset segregation is one of the core institutional safeguards in financial regulation designed to protect investor interests and prevent the spillover of institutional bankruptcy risks. In traditional securities and futures markets, mature rules already exist across jurisdictions (e.g., SEC customer fund protection rules in the U.S., FCA's Client Asset Rules in the UK) ensuring brokers keep client funds separate from proprietary funds. For crypto asset exchanges, recent events—including the collapse of a major global exchange in late 2022 due to misuse of customer funds—have underscored the critical importance of asset segregation. Regulators universally recognize that platforms must not commingle users’ entrusted digital assets with their own, nor should they be allowed to unilaterally use customer assets for lending or investment, as doing so would severely harm investors in the event of financial distress. This has become one of the key regulatory red lines across major jurisdictions.

The EU’s Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA) sets clear requirements for the custody and segregation of client crypto assets. MiCA stipulates that authorized crypto-asset service providers (CASP) holding crypto assets on behalf of clients must legally and operationally segregate those client assets from their own[3]. Specifically, CASPs must clearly identify client assets on the distributed ledger and ensure accounting records distinguish tokens held by clients from those owned by the company[3]. MiCA further emphasizes that client assets are legally independent of the CASP’s property, meaning that even in the event of insolvency, creditors cannot claim against the crypto assets held in trust for clients[25]. In other words, clients retain ownership or beneficial rights over their entrusted assets, which do not convert into general claims upon platform failure. This provision aligns with existing EU principles for investor asset segregation in securities markets. The formal text of MiCA published in June 2023 (Regulation (EU) 2023/1114), particularly Articles 67 and 68, details CASP custody obligations and asset segregation measures, including maintaining separate accounting for client and proprietary assets at technical and operational levels, and establishing internal controls and audit mechanisms to ensure effective segregation[26][27]. The EU aims to draw lessons from past crypto platform failures, eliminate legal uncertainty regarding asset ownership, and provide investors with bankruptcy remoteness protections similar to those in traditional finance.

At the U.S. federal level, there is currently no unified legal code specifically governing crypto asset custody, though some states and regulatory agencies have taken action. Notably, New York State Department of Financial Services (NYDFS), known for its strict oversight, issued guidance in January 2023 for institutions holding crypto custody licenses (i.e., those with a New York BitLicense or trust charter). NYDFS explicitly requires crypto custodians to “separately account for and segregate customer virtual currency from their own.” This can be achieved by creating individual wallets per customer, using internal classified ledgers, or placing all client assets into a pooled account strictly segregated from proprietary funds. Regardless of method, custodians must ensure customer assets are not included on their balance sheets and cannot be used for any purpose beyond secure custody. NYDFS also reaffirmed that custodians must not misuse, lend, or encumber customer assets without explicit client instructions. This guidance is seen as NYDFS’s regulatory response to recent industry scandals (such as the Celsius and FTX cases), where courts debated whether deposited crypto assets belonged to customers or became part of bankruptcy estates, resulting in investor losses. NYDFS’s rule establishes the priority of customer assets over other creditor claims. Although applicable only to entities with business ties to New York, given the state’s influential role in crypto regulation, this guidance is widely viewed as a benchmark for client asset segregation in U.S. practice. Other states like Wyoming have similar provisions in their Digital Asset Acts, recognizing the legal nature of entrusted digital assets as client-owned, thereby providing bankruptcy remoteness protection.

The Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission (SFC), in its 2023 "Guideline on Virtual Asset Trading Platform Operators," lists “proper asset custody” as one of the core principles that licensed platforms must follow[5]. According to the guideline, platforms must take measures to ensure the safekeeping of client virtual assets, including storing the vast majority of client assets in high-security cold wallets and setting strict withdrawal limits and multi-signature permissions for hot wallets. Additionally, the guideline mandates “holding client assets separately,” meaning platforms must clearly distinguish clients’ virtual assets from their own. In practice, licensed Hong Kong platforms typically deposit client fiat funds into separate trust accounts and store client crypto assets in dedicated wallet addresses or custodial accounts to achieve legal and operational isolation. For example, some platforms state that 98% of client assets are stored in cold wallets managed by independent custodians, with only 2% available for daily withdrawals, and regularly report asset reserves to regulators. These measures aim to prevent platforms from misappropriating client assets for proprietary trading or other uses and to minimize investor losses in extreme scenarios such as platform bankruptcy or hacking. By year-end 2023, the SFC further issued a notice emphasizing strong governance and auditing of client asset custody, requiring senior management to regularly review custody arrangements and private key management processes and introducing external audits to verify client asset holdings, enhancing transparency. These requirements highlight Hong Kong regulators’ emphasis on client asset security, aiming to avoid repeating overseas platform collapses and uphold Hong Kong’s reputation as a compliant crypto market.

Singapore’s MAS similarly evaluates applicants’ custody solutions and internal controls during the licensing process for digital payment token service providers, ensuring client assets are not misused. While Singapore has not yet enacted specific client asset segregation legislation, MAS guidance recommends that licensed institutions store client tokens in separate on-chain addresses, apart from operational funds, and establish daily reconciliation and proof-of-reserves mechanisms. In Japan, the FSA urged crypto exchange operators as early as 2018 to implement “trustification” of client assets—entrusting client fiat deposits to third-party trust institutions—while requiring at least 95% of client crypto assets to be stored offline. The 2019 amendment to Japan’s Financial Instruments and Exchange Act formally classified crypto assets as financial instruments and mandated daily reconciliation of client assets to ensure holdings meet required levels, with immediate regulatory reporting if shortfalls occur. This effectively establishes a client asset reserve regime—a unique form of segregation requirement.

In summary, client asset segregation has become a shared regulatory baseline across jurisdictions. Whether in Europe, the Americas, or the Asia-Pacific region, regulators require crypto asset trading platforms—through explicit laws or administrative guidance—to independently hold and separately account for client assets, prohibiting their treatment as corporate property or unauthorized use[25]. Implementing this requirement helps protect investors from insider appropriation or creditor seizure, enhancing market confidence. Nevertheless, institutions operating across jurisdictions must still pay attention to specific compliance variations. For example, some regions require third-party independent custodians, while others allow self-custody provided capital adequacy or insurance requirements are met. These differences will be discussed in later sections. Regardless, “not misusing client assets” is a red line among red lines—any deviation may invite severe regulatory sanctions or even criminal liability.

03 Regulatory Red Line Consensus: Combating Market Manipulation and Preventing Conflicts of Interest

This chapter examines two market fairness-related baselines: anti-market manipulation and conflict of interest prevention.

3.1 Anti-Market Manipulation: Market Integrity and Fraud Prevention

The price volatility of crypto asset markets and their relative lack of traditional market infrastructure make them vulnerable to manipulative behaviors, including wash trading, pump-and-dump schemes, insider trading, and market hype. If left unchecked, rampant market manipulation not only harms investor interests but could also undermine market pricing functions and erode public trust in crypto markets. Therefore, major jurisdictional regulators generally treat combating market manipulation and insider trading as regulatory red lines, requiring trading platforms and related intermediaries to implement measures to monitor and prevent suspicious trading activities and report to regulators when necessary, ensuring fair and orderly markets[4]. Legally, many countries classify serious market manipulation as criminal offenses, subject to penalties consistent with those in traditional financial markets.

In the United States, anti-manipulation laws for securities and derivatives markets are well-developed. For digital tokens classified as securities, Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and SEC Rule 10b-5 prohibit any market manipulation or securities fraud; insider trading is also prohibited and penalized under federal securities law and case law. For digital assets deemed commodities (such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, as classified by U.S. regulators), the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) empowers the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to oversee derivative markets and take enforcement actions against fraudulent manipulation in spot markets. In recent years, U.S. enforcement agencies have actively used these laws to crack down on illegal behavior in crypto markets: for example, in 2021, the U.S. Department of Justice prosecuted an insider trading case involving cryptocurrency, charging an exchange employee with profiting by purchasing tokens ahead of listing announcements; simultaneously, the SEC filed parallel securities fraud charges, asserting the relevant tokens were securities. This marked the first enforcement action for “insider trading” in the crypto space, demonstrating that the U.S. will not relax penalties for unfair trading based on asset form. Notably, the CFTC sued executives of a crypto trading platform in 2021, accusing them of tacitly allowing users to inflate trading volume, creating false liquidity to mislead the market, and pursued liability under anti-manipulation clauses in the Commodity Exchange Act. Although the U.S. lacks dedicated legislation targeting manipulation in the crypto spot market, regulators have conducted multiple enforcement actions leveraging existing laws (securities law, commodity law, and anti-fraud provisions). Meanwhile, state attorneys general, such as New York’s, have used broad anti-securities fraud authorities like the Martin Act to investigate suspected manipulation on trading platforms (e.g., the 2018 NYAG investigation into volume falsification by multiple exchanges). Overall, the U.S. emphasizes the principle of “regulatory neutrality”—even for emerging crypto assets, manipulation similar to that in traditional securities/commodities may trigger corresponding legal sanctions.

The EU has established a comprehensive ban on insider trading and market manipulation through the Market Abuse Regulation (MAR) in traditional securities markets. However, MAR applies mainly to regulated financial instruments and does not directly cover most crypto assets. To fill this gap, the EU introduced market integrity obligations for crypto assets in MiCA. Provisions such as Article 80 of MiCA prohibit anyone engaged professionally in crypto trading from using inside information or engaging in manipulative behavior. Additionally, MiCA requires CASPs operating trading platforms to establish market surveillance mechanisms capable of detecting and addressing market abuse[4]. Specific measures include: embedding monitoring algorithms in trading systems to detect signs of possible manipulation, such as unusually large orders or frequent order cancellations; maintaining orderly trading during sharp price fluctuations to prevent market manipulation; setting price fluctuation or volume thresholds to automatically reject out-of-range orders; and promptly reporting suspicious manipulation or insider trading to competent authorities. Moreover, MiCA mandates continuous public disclosure of bid/ask quotes and depth information, along with timely release of trade data, to enhance market transparency and reduce opportunities for opaque operations. These provisions effectively borrow from EU securities market experience, applying the principle of “same business, same risk, same rules” to crypto asset trading. In 2025, the EU is considering, within a new AMLR proposal, banning anonymous transactions and privacy coins (see below)—a move aimed at preventing dark pool manipulation by increasing traceability. On enforcement, as MiCA takes effect, national securities regulators (such as France’s AMF and Germany’s BaFin) will have clear authority to investigate manipulation in crypto markets. For example, someone promoting coordinated buying of a token in a Telegram group to inflate prices before selling for profit could be found in violation of market manipulation prohibitions and penalized. Thus, the EU is progressively extending market abuse regulation into the crypto domain, achieving regulatory continuity and consistency.

The Hong Kong SFC requires licensed virtual asset trading platforms to establish market surveillance departments or systems to monitor abnormal trading in real time. According to SFC guidelines, platforms must promptly identify and block attempts to manipulate the market, such as matched trades across linked accounts or false order submissions, and retain logs for regulatory inspection. Upon detecting significant suspicious manipulation, platforms must report to the SFC and law enforcement. While Hong Kong has not yet included crypto assets under market manipulation offenses in the Securities and Futures Ordinance (as most crypto assets are not defined as securities), licensed platforms still have compliance obligations to ensure market fairness. This represents a “licensing condition-based regulatory approach.” In Singapore, MAS applies market manipulation and insider trading provisions under the Securities and Futures Act (SFA) to digital tokens listed on regulated markets (e.g., recognized exchanges) if they are deemed securities or derivatives. For pure crypto asset trading not falling under financial instrument definitions, Singapore currently relies mainly on industry guidelines urging self-monitoring by traders. However, MAS has repeatedly warned about money laundering and manipulation risks in crypto markets, cautioning investors. In 2025, Singapore is considering amending relevant laws to bring certain token trading activities affecting public interest under the Financial Markets Conduct Act, such as prohibiting dissemination of false or misleading information influencing token prices, to address insufficient enforcement basis.

Notably, to assist regulators and platforms in fulfilling monitoring duties, specialized blockchain analytics companies and regtech solutions are increasingly applied to anti-manipulation efforts. Some trading platforms use on-chain analysis tools to monitor fund rotations across multiple accounts to detect “multi-account collusive manipulation”; others have developed AI models capable of identifying anomalous price patterns and order book behavior. Regulators are also increasingly relying on such technologies to improve monitoring efficiency. For example, the U.S. SEC has established a dedicated crypto asset task force using big data analytics to examine exchange trading records, detect unusual volatility, and investigate potential artificial manipulation. ESMA and national regulators in the EU are exploring the creation of cross-platform crypto transaction reporting repositories to identify cross-market manipulation.

In conclusion, combating market manipulation and insider trading is a shared regulatory red line across jurisdictions, differing only in execution methods due to varying regulatory scopes and legal authorizations. The trend suggests that as crypto markets integrate more deeply with traditional finance, countries will increasingly seek to bring crypto trading under existing market regulatory frameworks for equal constraints. For example, the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB) 2023 recommendations emphasize that countries should ensure “effective regulation and supervision of crypto asset markets to maintain market integrity,” including equipping themselves with sufficient enforcement tools to curb manipulation and fraud. This global guiding principle is expected to translate into more explicit regulatory requirements across jurisdictions, meaning that manipulating crypto markets in New York, London, or Singapore will carry legal consequences. For market participants, this implies a fairer and more transparent trading environment—an essential condition for long-term industry health.

3.2 Conflict of Interest Prevention: Business Separation and Internal Governance

Conflict of interest prevention is a fundamental requirement to ensure financial institutions fulfill fiduciary duties and protect client interests. In crypto asset trading, potential conflicts include: platforms acting simultaneously as market operators and engaging in proprietary trading or controlling affiliated market makers, possibly profiting from client order information; platforms issuing and listing their own tokens, creating price support and information asymmetry issues; and executives or employees using sensitive market information for personal trading (insider trading). Without proper regulation, these conflicts can harm client interests and market fairness, potentially triggering systemic risks (as seen when certain exchanges collapsed due to affiliate high-risk trading consuming customer assets). Consequently, regulators worldwide regard preventing and managing conflicts of interest as a red line, requiring crypto asset service providers to establish internal controls and institutional arrangements to identify, mitigate, and disclose potential conflicts.

MiCA imposes clear and mandatory requirements on CASPs regarding conflict of interest management. Under MiCA Article 72[28], crypto-asset service providers must establish and maintain effective policies and procedures to identify, prevent, manage, and publicly disclose potential conflicts of interest. These conflicts may arise between: (a) the service provider and its shareholders, directors, or employees; (b) different clients; or (c) the provider and its affiliates performing multiple business functions. MiCA requires service providers to assess and update their conflict of interest policies at least annually and take all appropriate measures to resolve identified conflicts. Additionally, service providers must prominently disclose on their websites the nature, sources, and mitigation steps for general conflicts of interest, informing clients. For CASPs operating trading platforms, MiCA further stipulates special procedures to avoid conflicts of interest between themselves and clients in trading, including preventing matching against proprietary orders in the order-matching system and restricting staff from trading based on non-public information. MiCA also authorizes technical standards to detail disclosure formats, indicating the EU views conflict of interest as a domain requiring strong regulatory intervention. One motivation behind MiCA was learning from past risks arising from proprietary and affiliate trading on exchanges, ensuring “fair play”: platforms cannot act as both casino operators and gamblers while deceiving other players. Notably, MiCA not only requires service providers to manage their own conflicts but also includes similar provisions for issuers of asset-referenced stablecoins (e.g., requiring disclosure of potential conflicts arising from managing reserve assets), reflecting the EU’s regulatory demand for all entities to establish conflict-of-interest firewalls.

Traditional financial markets in the U.S. have long-standing conflict-of-interest frameworks (e.g., separation of exchange and broker-dealer proprietary trading, bank firewall rules). For the crypto sector, there is currently no dedicated regulation mandating business separation or banning proprietary trading, but regulators have repeatedly expressed concerns about vertical integration risks. For example, a CFTC commissioner stated publicly in 2024 that integrated structures like FTX—combining exchange, brokerage, market-making, and custody roles without external oversight—created massive conflicts of interest and risk, urging regulators to set rules limiting such vertically integrated structures. The statement noted that the FTX collapse “highlighted the serious harm caused by the absence of conflict-of-interest regulation.” Although FTX was not fully regulated in the U.S., its failure prompted reflection among lawmakers and regulators: should rules similar to the “separation of trading and advisory businesses” in securities law be established for crypto exchanges? Currently, some congressional proposals (e.g., the 2022 draft Digital Commodities Consumer Protection Act) have considered prohibiting crypto exchanges from engaging in activities conflicting with client interests, such as banning the lending of customer assets or restricting affiliate participation in platform trading, though these bills have not passed. Meanwhile, U.S. regulators have promoted conflict-of-interest prevention through enforcement. For example, the SEC has cautioned platforms like Coinbase that allowing executives to sell tokens early or investing in listed projects may constitute conflicts of interest harmful to investors, necessitating full disclosure and control. Similarly, the DOJ has prosecuted individuals for allegedly profiting from non-public listing information, punishing insider conflict behaviors. Additionally, at the licensing level, NYDFS requires BitLicense holders to submit conflict-of-interest policies detailing restrictions on personal trading by directors and executives and measures to mitigate potential conflicts from multiple business lines. These actions indicate that while the U.S. lacks MiCA-style comprehensive norms, enforcement and regulatory moves are gradually making conflict-of-interest prevention a focal point in crypto platform compliance.

Hong Kong SFC explicitly requires licensed platforms to avoid conflicts of interest in its "Virtual Asset Trading Platform Operator Guidelines." Specific measures include: platforms must not engage in any form of proprietary trading (i.e., not acting as "market makers"); if affiliated companies within the platform group engage in market-making, they must report to the SFC and ensure strict information barriers ("Chinese Walls") to prevent insider information leaks; personal crypto trading by platform executives and employees is restricted, requiring declaration and internal compliance approval. Additionally, if a platform intends to list tokens with which it has an interest (e.g., project tokens it has invested in or its native token), the SFC requires full disclosure and may deny listing approval to prevent “listing with one hand and harvesting with the other.” This approach aligns with Hong Kong’s securities market practices, such as separating broker-dealer proprietary trading from agency business to avoid conflicts. After the SFC began issuing licenses in 2023, Hong Kong’s first licensed platforms declared in public materials that they do not engage in proprietary trading or compete with clients, aiming to gain investor trust. This creates a regulatory red line: platforms serve solely as intermediaries, not as market counterparties, reducing conflicts of interest structurally.

International organizations also focus on this issue. The Financial Stability Board (FSB), in its July 2023 high-level recommendations on crypto regulation, explicitly stated that jurisdictions should “ensure that crypto asset service providers combining multiple functions are subject to appropriate regulatory oversight, including requirements for conflict of interest and functional separation”[26]. This calls globally for standardizing business models of crypto trading platforms, mandating the split of conflicting functions when necessary (e.g., separating trading from custody, brokerage from market-making), to prevent one entity from being both player and referee. FSB’s stance is supported by IOSCO: in its 2022 consultation report, IOSCO recommended regulators require crypto exchanges to disclose proprietary trading, restrict employee misconduct, and possibly draw from structural separation experiences in traditional finance to reduce conflicts. It is foreseeable that under FSB and IOSCO advocacy, the principle of “same risk, same function, same rules” will gradually apply to conflict-of-interest management, leading to unified international standards in the near future.

In sum, conflict-of-interest prevention has been incorporated into the basic regulatory requirements for the crypto asset industry across jurisdictions. From MiCA’s mandatory rules in the EU to licensing conditions in Hong Kong and Singapore, and from U.S. regulators’ statements to enforcement actions, a clear message is conveyed: intermediary platforms and similar entities must establish sound internal control mechanisms to prevent profiting from client-disadvantageous information, and must promptly disclose and stop such behavior when detected. Establishing this red line helps restore market confidence damaged by various scandals and promotes industry development toward greater transparency and integrity. For operating institutions, this means investing more resources in internal governance—such as appointing independent compliance officers to supervise trading, conducting regular conflict-of-interest risk assessments, and training employees on ethical standards—to meet regulatory expectations and maintain their reputations.

04 Regulatory Divergence: Stablecoin Regulatory Path Differences

Stablecoins—cryptographic tokens pegged to fiat currencies or other assets—have rapidly developed globally, attracting intense attention from regulators. On one hand, stablecoins may enhance payment efficiency and financial inclusion; on the other, their widespread use could threaten financial stability and monetary sovereignty, especially when issuance lacks adequate reserves or transparency, harboring collapse risks (e.g., the 2022 algorithmic stablecoin UST crash). Consequently, countries are exploring regulatory paths for stablecoins. However, due to differences in legislative philosophy and financial systems, stablecoin regulation has become one of the most divergent cross-jurisdictional issues. Key differences lie in: permitted issuers, reserve and capital requirements, investor protection measures, and usage restrictions.

4.1 Licensing and Limits for Fiat-Backed Stablecoins

The EU, under MiCA, divides stablecoins into two categories: electronic money tokens (EMT), pegged to a single fiat currency; and asset-referenced tokens (ART), pegged to baskets of assets or non-fiat values. MiCA imposes strict access and oversight on both. For EMT, issuers must obtain credit institution (bank) or electronic money institution licenses and issue tokens under regulatory approval. Issuers must hold highly liquid reserve assets (mainly corresponding fiat deposits or high-quality government bonds) equal in value to issued tokens to ensure 1:1 solvency. MiCA also prohibits paying interest on EMT holdings to prevent competition with deposits. Most distinctively, to prevent non-euro stablecoins from undermining monetary policy, MiCA introduces transaction usage caps: for stablecoins not pegged to the euro (e.g., USD-pegged USDT), daily transaction volume must not exceed 200 million euros or 1 million transactions; otherwise, issuers must restrict usage (including suspending issuance or redemption if necessary). This dual threshold of “200 million euros/day” and “1 million transactions/day” aims to prevent any single stablecoin from becoming overly dominant and replacing the euro in payments. This is a uniquely preventive EU regulatory measure, drawing significant industry attention (dubbed the “hard cap on stablecoin transactions”). Additionally, MiCA imposes stricter requirements on issuers deemed significant (Significant EMT/ART), including more frequent reporting, tighter liquidity management, and reserve custody rules. Starting in 2024, MiCA’s stablecoin provisions will take effect first, requiring full compliance after the transition period or barring provision of stablecoin services in the EU. This framework represents the world’s most comprehensive and stringent stablecoin regulation to date, aligned with traditional financial standards for electronic money institutions and banks issuing payment instruments.

Compared to the EU, the U.S. currently lacks federal-level dedicated stablecoin legislation, creating a major regulatory gap. In recent years, the U.S. Congress has produced multiple reports and draft bills on stablecoins. The 2021 President’s Working Group (PWG) report recommended restricting stablecoin issuance to regulated depository institutions (e.g., banks) and called for congressional legislation. Subsequently, proposals such as the Stablecoin Transparency and Protection Act and the Digital Commodities Stablecoin Act emerged but failed to pass due to political disagreements. As a result, under current law, stablecoin issuers rely on existing frameworks: some companies regulated under trust charters (e.g., Paxos, Circle via state trust licenses) issue stablecoins under state financial regulator oversight; others without licenses (e.g., Tether) operate outside U.S. regulation, constrained only partially due to their banking relationships falling under U.S. law. Federal regulators can only exert indirect pressure—for example, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) allowed national banks to issue stablecoins in 2021 under prudent conditions, while the Fed and FDIC warned banks to cautiously participate in stablecoin reserve activities. At the state level, NYDFS pioneered reserve and audit requirements for regulated stablecoins (e.g., BUSD, USDP approved by NYDFS); in 2022, NYDFS issued guidance requiring dollar-pegged stablecoins issued in New York to be backed 100% by cash or short-term U.S. Treasuries, redeemable daily with no interest. Wyoming allows digital asset reserve banks (SPDIs) and new stablecoin institutions to issue stablecoins via innovative laws, though no successful cases exist yet.

In the absence of unified rules, the U.S. stablecoin market is highly fragmented: large players like Tether and Circle voluntarily maintain high reserves and regularly publish proof-of-assets, but vulnerabilities remain (e.g., TerraUSD’s algorithmic coin grew under regulatory gaps before collapsing). This regulatory void has raised alarms among U.S. lawmakers, prompting renewed congressional efforts in late 2023 to advance a “Stablecoin Regulation Act,” aiming to establish a federal licensing system and grant the Fed supervisory authority over non-bank stablecoin issuers. However, the legislative process remains uncertain. In this context, U.S. authorities temporarily manage risks through enforcement: for example, the SEC has issued warnings to certain stablecoins suspected of being securities (e.g., a social media company’s dollar-pegged stablecoin), while the CFTC considers mainstream stablecoins as commodity assets and retains enforcement rights. Overall, U.S. stablecoin regulation remains in a state of “lagging legislation, fragmented state-level actions, and scattered federal guidance,” markedly different from the EU’s comprehensive legislative model.

Japan adopts a relatively conservative approach to stablecoin regulation. In June 2022, Japan’s Diet passed amendments to the Funds Settlement Act and related laws, formally defining stablecoins’ legal status and issuance qualifications. The new law classifies stablecoins as “electronic payment instruments,” permitting issuance only by regulated legal entities: registered banks, limited remittance service providers (requiring high capital), or trust companies in Japan[6]. This excludes general private enterprises, meaning entities like Tether cannot legally issue stablecoins in Japan. The law also stipulates that qualified stablecoins must be pegged to yen or other fiat currencies and be redeemable at par by holders. Additionally, it prohibits issuing algorithmic stablecoins or other unsecured forms. For reserves, a 100% fiat margin must be deposited with regulated institutions.

Moreover, Japan’s FSA is extremely cautious about foreign stablecoins entering the Japanese market; currently, major overseas stablecoins (like USDT) are largely unlisted on Japanese exchanges, while yen-pegged coins issued by trust companies (e.g., Mitsubishi UFJ Trust’s “Progmat Coin”) are under testing. In 2024, Japan is discussing further restrictions: for example, the FSA proposed disallowing ordinary banks from directly issuing stablecoins on public blockchains (deeming it high-risk, reserving issuance to trust banks), and requiring full application of KYC/Travel Rule to stablecoin transfers. Under Japan’s model, stablecoins resemble bank deposit substitutes, strictly governed by banking and payment regulations, reflecting a strong emphasis on financial stability and consumer protection. This model offers high security but risks suppressing non-bank innovation. Currently, no large-scale stablecoin circulation exists in Japan, but if major banks proceed with yen-pegged stablecoins, they will operate entirely under regulatory oversight, keeping risks relatively manageable.

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) issued a discussion paper in 2022, explicitly disallowing algorithmic stablecoins and planning to focus on regulating fiat-referenced payment stablecoins. The draft “Stablecoin Ordinance” was completed in 2023 and will take effect in August 2025[7]. The ordinance requires issuers of fiat-pegged stablecoins circulating or issued in Hong Kong to obtain a license from the HKMA. Applicants must meet strict conditions: establishing a physical entity in Hong Kong, possessing minimum statutory capital, and implementing risk management and technical audits. The ordinance mandates 100% reserve assets (limited to highly liquid assets) and par-value redemption upon holder request. It also grants the HKMA inspection powers to review reserve status and operations. Hong Kong’s distinctive feature is not limiting issuance to banks but ensuring all issuers undergo prudential regulation akin to banks. This may leave room for non-bank fintech companies to issue stablecoins, albeit with high regulatory costs. Hong Kong plans to complete initial licensing by 2024–25, emphasizing a gradual, small-scale rollout. Notably, the ordinance brings stablecoins under AML law, requiring issuers and distributors to fulfill KYC/AML obligations. This positions Hong Kong as another Asian financial center setting a stablecoin regulatory benchmark, differing from Singapore’s current reliance on guidance without legislation. For the market, Hong Kong’s framework offers a compliant path for stablecoin issuance and operation, likely attracting licensed-oriented issuers.

4.2 Capital and Reserve Requirements for Non-Fiat-Backed Stablecoins (Asset-Referenced Tokens)

Besides single-fiat-pegged stablecoins, some are backed by baskets of fiat, commodities, or crypto assets (e.g., the original Libra concept, pegged to multiple reserve assets) or maintain pegs via algorithmic plus collateral mechanisms. These “asset-referenced tokens” (ART) have more complex value stabilization mechanisms and higher risks. Regulators generally view ART with greater caution. Especially after the Libra project (later renamed Diem) triggered global regulatory backlash in 2019, most jurisdictions clearly stated such multinational basket coins might threaten financial sovereignty and stability and should face strict controls.

The EU’s MiCA brings asset-referenced tokens (ART) under regulation, requiring issuers to obtain licenses and comply with a series of requirements similar to EMT, including whitepaper disclosures, reserve custody, capital, and liquidity planning. However, given ART’s non-single-fiat peg, MiCA imposes stricter rules: first, ART issuers must hold higher minimum capital (at least €350,000 or 2% of reserve value), exceeding EMT issuer requirements. Also, ART issuers must establish clear reserve asset custody policies, ensuring reserves are fully isolated from issuer-owned assets and cannot be misappropriated. MiCA allows reserves to be held by qualified custodians (e.g., licensed CASP custodians or banks) and requires high diversification to reduce correlation risks. Additionally, ART issuers must establish regular audit mechanisms, disclosing reserve composition and audit reports quarterly to enhance transparency. For significant ART, MiCA authorizes regulators to impose additional requirements, such as limiting business scale or demanding more detailed risk analyses. MiCA also prohibits ART issuers from offering any profit incentives to holders, aiming to prevent ART from becoming de facto investment products. Overall, MiCA’s ART requirements span governance, risk management, and user protection, aiming to contain risks at controllable levels.

After the Libra incident, multiple U.S. agencies jointly pressured the project, forcing design changes and eventual termination. Though no dedicated law exists, it can be inferred that if a Libra-like ART emerged, the U.S. might use Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act (systemically important payment tools) or securities law to regulate it. For example, if an ART involves a basket of securities as reserves, the SEC might classify it as an ETF share requiring registration; if it involves significant payment functionality, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) might designate the issuer as systemically important, subject to Fed oversight. Currently, no large-scale ART operates in the U.S. market (mainstream stablecoins are mostly single-currency pegged), so regulatory divergence mainly reflects differing stances. Federal Reserve officials have stated that multi-currency stablecoins might require special central bank review. Some U.S. think tanks suggest treating such stablecoins as “shadow bank money,” requiring issuers to follow strict portfolio limits and reserve requirements like money market funds. But lacking practical cases, the U.S. has not formed a fixed path. In enforcement, if an ART causes investment losses, regulators might invoke commodity or securities laws. For example, Ampleforth’s algorithmic stablecoin was investigated by the SEC for potentially selling securities via ICO, showing algorithmic designs don’t exempt securities law. This illustrates U.S. regulation’s “principle-driven” nature: no dedicated law, but flexible application of relevant laws case by case.

Singapore consulted the public on stablecoins in 2022, proposing rules for single-currency stablecoins (e.g., reference currency must be G10, minimum reserve quality), but leans against encouraging multi-asset-backed stablecoins. MAS’s approach is to first regulate single-currency stablecoins well, then decide on complex structures based on international consensus. Hong Kong’s current ordinance mainly targets fiat-pegged coins, directly excluding non-fiat-pegged tokens (e.g., algorithmic, commodity-backed) from licensing consideration. Korea’s FSC declared in 2023 that exchanges cannot trade algorithmic stablecoins and holds negative views on any yield-bearing or complex-mechanism stablecoins. Japan, allowing only fiat-pegged issuance, naturally has no ART space. Overall, stablecoin regulation differs greatly between Europe and the U.S.: the EU has built a detailed framework via MiCA, especially setting clear requirements for international basket coins; the U.S. remains in discussion, focusing short-term on single-currency stablecoin legislation. Major Asian economies are mostly cautious and restrictive. This divergence means stablecoin businesses face vastly different compliance demands globally. Operating in the EU requires licensing and daily transaction volume monitoring; in the U.S., despite no clear licensing, firms face uncertain regulatory risks and potential enforcement; in Japan or Hong Kong, direct licensing restrictions or bans may apply. Thus, regulatory divergence here is especially pronounced and remains a key challenge for future international coordination.

05 Regulatory Divergence: Market Access and Innovation Boundaries

This chapter discusses three areas with significant cross-jurisdictional regulatory differences: crypto derivatives trading regulation, privacy coin legality, and regulatory exploration of real-world asset tokenization (RWA) and decentralized finance (DeFi). These areas involve investor protection, criminal enforcement, technological anonymity, and financial innovation boundaries, leading to diverse national strategies without unified international standards.

5.1 Market Access and Investor Protection for Crypto Derivatives

Crypto derivatives refer to contract products like futures, options, and contracts for difference (CFDs) based on crypto asset prices. These products enable hedging and speculation, amplifying both gains and risks. High leverage and volatility make them extremely dangerous for ordinary investors. Traditional financial

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News