Is there still a chance for probation after being arrested in a case involving programmers and operating an online gambling platform using cryptocurrencies?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Is there still a chance for probation after being arrested in a case involving programmers and operating an online gambling platform using cryptocurrencies?

How can we better understand the psychology of case handlers?

Written by: Shao Shiwei, Manqin

Success Story

In criminal cases, many clients and their families assume that a lawyer's role is simply to "argue forcefully and eloquently." In reality, however, in cases with clear legal characterization and limited sentencing discretion, truly effective defense work often involves more than just confrontation. Instead, it hinges critically on the lawyer’s communication skills.

This is especially true under the current leniency system for plea bargaining, where the prosecution's sentencing recommendation often plays a decisive role in the final outcome. At this stage, whether a lawyer can understand the psychology of the case handlers—identifying what they genuinely care about in a specific case—and engage in professional dialogue based on shared ground, frequently determines the trajectory of the case.

In other words, a lawyer’s expertise lies not only in mastery of legal principles, but also in their ability to earn the trust of the case handlers. When a lawyer’s opinions are accepted, it often opens space to secure a more lenient sentence for the client.

So how can one better understand the mindset of case handlers? There is no standard answer—it largely depends on accumulated experience—but it’s not entirely without guidance. This article illustrates such strategies through a case handled by attorney Shao Shiwei involving virtual currency settlements and charges of operating a gambling site.

A Programmer Accused of Operating a Gambling Site via Virtual Currency Settlements

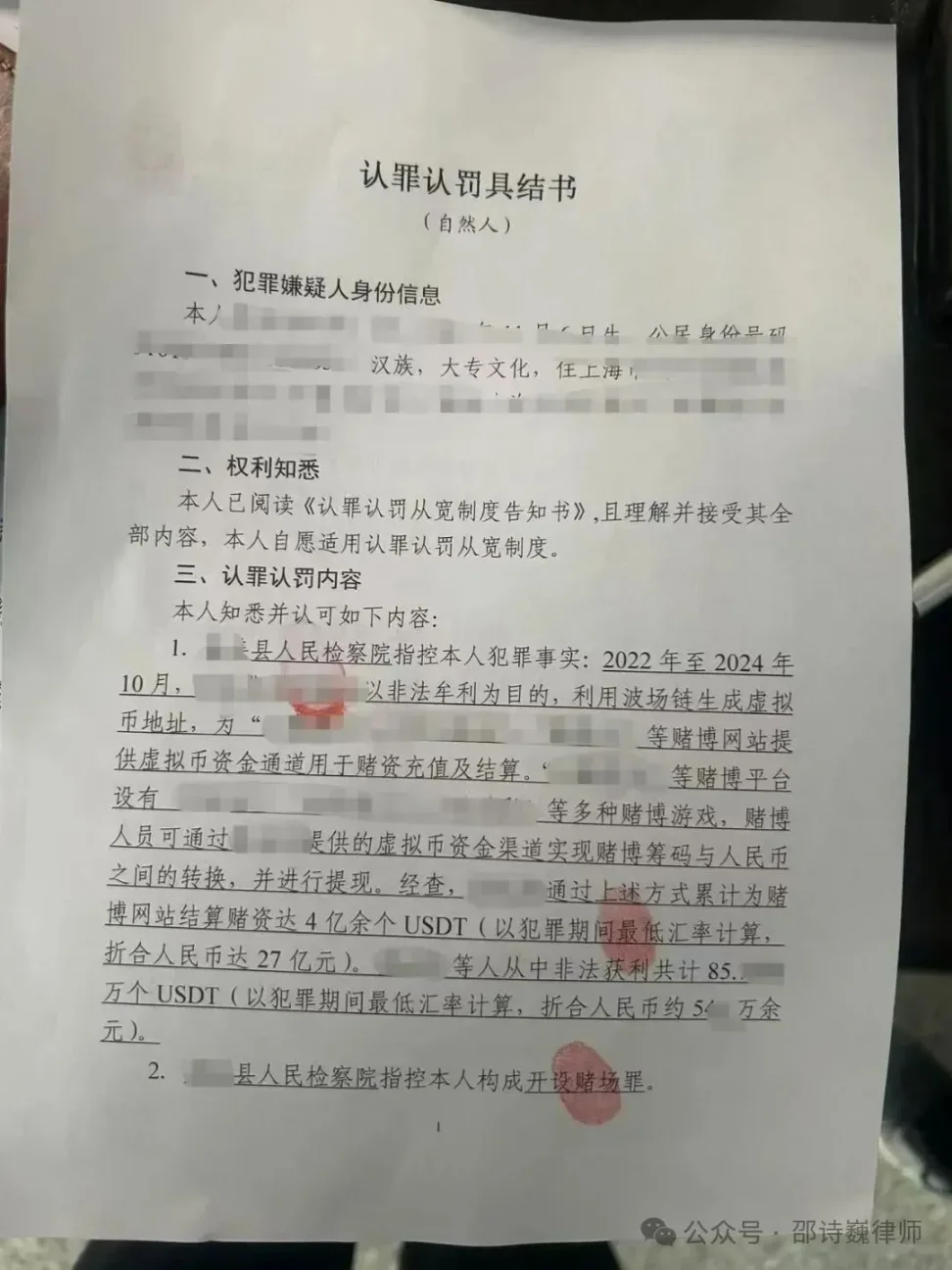

Several months ago, I took on a case involving the charge of operating a gambling site: my client was a programmer accused of providing virtual currency settlement services for multiple overseas gambling websites.

According to the public security authorities, over the past two years, the programmer had facilitated settlement of over 400 million USDT in gambling funds—equivalent to approximately 2.7 billion RMB—for several gambling platforms, personally profiting over 900,000 USDT (about 6 million RMB).

Under Article 303 of the Criminal Law, cumulative gambling funds exceeding 300,000 RMB or illegal gains over 30,000 RMB constitute “serious circumstances,” typically punishable by five to ten years’ imprisonment.

Facing a case with such clear characterization, solid data, and massive amounts, what could a lawyer possibly do? Where was the room for defense?

An Evidence Deadlock: “No One Left to Confirm the Truth”

When I took over the case, the police investigation had already concluded, all evidence collected, and the file transferred to the procuratorate for review and prosecution.

This article focuses on the lawyer’s communication efforts during the prosecutorial phase, as since the implementation of the leniency system, the prosecutor’s sentencing recommendation has become pivotal to the final sentence imposed by the court.

From initial discussions with the family, I learned that the client actually had two other partners; the three operated as a team, independently contacting gambling platforms to provide services. However, one partner had passed away, and the other disappeared after the incident. The client himself was arrested at the airport upon returning home, apprehended immediately by waiting officers.

From a defense perspective, understanding the division of labor among the three—and how the 900,000+ USDT profits were distributed—was crucial. Since the client was caught unexpectedly at the airport, he couldn’t claim self-surrender. Beyond typical arguments around the amount of gambling funds and profits, the only viable path to reduce his sentence below five years was securing recognition as an accomplice.

Yet this was a classic “no one left to confirm the truth” scenario. As the case handler once bluntly told the client during interrogation: “Who knows if what you’re saying is true? All we see is that you built the smart contract logic, and you’re the one communicating with the gambling platforms on Telegram. You say you have two partners—A hasn’t left a trace, and B has been dead for years. So how do we know you didn’t do it all yourself? Every piece of evidence points only to you!”

To be honest, even now, I don’t know for sure whether the other two partners ever existed. But from a defense standpoint, the absolute truth isn’t the point—the key is leveraging existing evidence to secure a lighter sentence for the client.

Can Researching Past Local Cases Help?

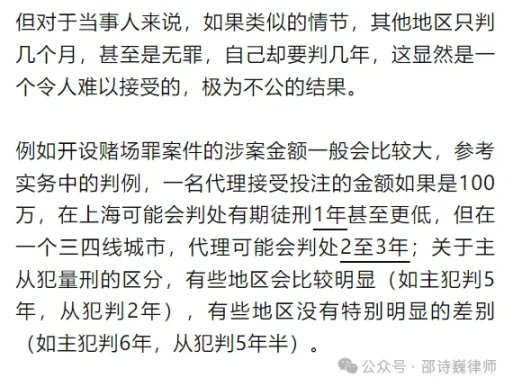

Beyond statutory law, prior local judgments are vital in shaping defense strategy. As I discussed in my previous article, “Different Judgments for Similar Cases? A Study on Territorial Jurisdiction in Criminal Cases” (shown below), even identical charges can result in divergent outcomes across regions—a not-uncommon phenomenon.

I conducted thorough research into past local cases involving “operating a gambling site” with “virtual currency settlements,” but the results were discouraging. For example:

In the case of Chen et al., defendants who provided financial settlement services for gambling platforms, handling over 90 million RMB, were all sentenced to actual prison terms;

In Fang’s case, despite returning 10 million RMB in illicit gains, the defendant still received a sentence exceeding five years;

Additionally, based on our team’s experience, some investigators consider the use of cryptocurrency transactions as an aggravating factor, per internal court guidelines.

This research reinforced my realization: in this jurisdiction, convictions for operating gambling sites almost invariably result in actual imprisonment. Worse, given the evidence, defending under the charge of aiding information network criminal activities (“Helping Information Network Crime Activity”—Bangxin crime) wasn’t viable—the client wasn’t an employee, and both intent and collaboration were clearly established, ruling out a secondary or auxiliary role.

Time was running short—by the time I received the case file, the review period was already well advanced. No time for hesitation. I dove straight into document review and began working.

Two Core Challenges

Nearly a thousand pages of case files and dozens of gigabytes of electronic data took me five full days to preliminarily sort through.

I identified two major difficulties:

First, the co-defendants were “unverifiable”—how could we establish the client’s role within the group? The police report made no mention of principal or accessory roles, nor any team structure. Every act—liaising with gambling platforms, building contract logic, Telegram communications, wallet control—was attributed solely to the client. Even no staff from the gambling sites had been apprehended, further reinforcing the impression that he acted alone.

Second, on-chain transaction data. Such data is inherently transparent and objective. Even if there were minor errors in the police tally, how much could realistically be deducted from 2.7 billion RMB in gambling funds and over 6 million RMB in profits?

Could we recommend arresting the other partners or platform personnel? We could suggest it, certainly. But these individuals had strong counter-investigation capabilities and were likely abroad. Given the mechanisms of criminal investigations, cross-border evidence collection and arrests of this nature are rarely feasible. Authorities typically won’t initiate complex international cooperation procedures for such requests.

So I needed to carefully plan my communication strategy: What should I say to the prosecutor? How should I say it? And how could I negotiate a reduced sentence?

How to Communicate? Is “Hardline Confrontation” Effective?

In practice, some lawyers adopt what we in the field call the “hardline” approach. These attorneys often display intense adversarial behavior, fiercely contesting legal issues, clashing directly with investigators, and sometimes using media exposure and public opinion to pressure the system toward favorable outcomes.

This style can be effective in high-profile, controversial acquittal-seeking cases. But in cases like this—where the charge is clear and the dispute centers on sentencing range—such confrontation is often ineffective, even counterproductive. From the judiciary’s perspective, poor cooperation and negative attitude may lead to harsher sentences—a common occurrence we’ve seen repeatedly.

Does this mean that for clear-cut cases like this, we should just “go through the motions” and accept the plea deal? Absolutely not. Even when guilt is undisputed, effective mitigation strategies can still secure lighter penalties.

Of course, the approach must be tailored to each case, considering not only the evidence but also the procedural stage, the individual investigator’s personality and working style, and their interpretation of laws and facts. Sometimes, the same case can take vastly different paths depending on who handles it.

The Initial Exchange with the Prosecutor

One morning, I met the assigned prosecutor. Arriving early, I waited outside before entering his office—a space overwhelmed by towering stacks of case files.

He looked extremely busy, phone ringing constantly, barely pausing between calls. I sat silently across from him, waiting for the right moment to speak.

Finally, the phone quieted. He looked up, briskly stating: “This case has no real disputes. Just wrap up the plea agreement soon—the timeline’s tight. We’ve got too many cases; the office wants to indict quickly.”

I seized the opening: “What’s your current thinking on sentencing?”

Flipping through the file, he replied impatiently: “He says the code was written by two partners? B’s been dead for years—how could B write it? And A? Not a single trace in the entire file. We don’t even know if A exists—probably made up. With this amount, judging from similar cases we’ve handled, he’s looking at seven to eight years at least.”

In that moment, I sensed his firm bias—he aligned completely with the police narrative.

Frankly, based solely on the file, it was understandable: he contacted the platforms; he built the contracts; he controlled the wallets (and not multi-signature ones); Telegram chats showed only him communicating. Though he claimed a fixed salary, he couldn’t explain profit splits, and never mentioned partners in early statements.

Under these circumstances—forget prosecutors—even an ordinary person would likely jump to the same conclusion.

How to Achieve Effective Communication?

Prior to the meeting, I had meticulously reviewed every key piece of evidence—my discussion was purposefully structured.

His initial reaction wasn’t surprising. For straightforward plea-bargaining cases with clear data, investigators often default to procedural processing.

But then I asked: “If the prosecution doesn’t return the case for further investigation and proceeds straight to indictment, do you think the judge might later demand additional evidence?”

That gave him pause. He stopped, put down his pen, and began taking notes.

Though the charge seemed uncontested, the case had numerous procedural and substantive flaws: virtual currency asset disposal procedures, methods of calculating涉案 amounts, and evidentiary standards. Moreover, hastily labeling the client as the principal offender could create downstream complications. If the defense insisted on remanding for reinvestigation, it would trouble the prosecutor—already handling his first crypto-related case. Most available evidence had already been collected; returning the case wouldn’t yield significant new material.

I watched his expression grow increasingly serious as he wrote. Good—he was taking me seriously.

We talked for two to three hours. Finally, he said: “Alright, your points make sense. I’ll note them down. I need to discuss with my superiors and verify some details with the police before getting back to you.”

I knew I’d achieved my goal.

In the following days, I maintained steady online communication, discussing key issues point by point.

Outcome Achieved

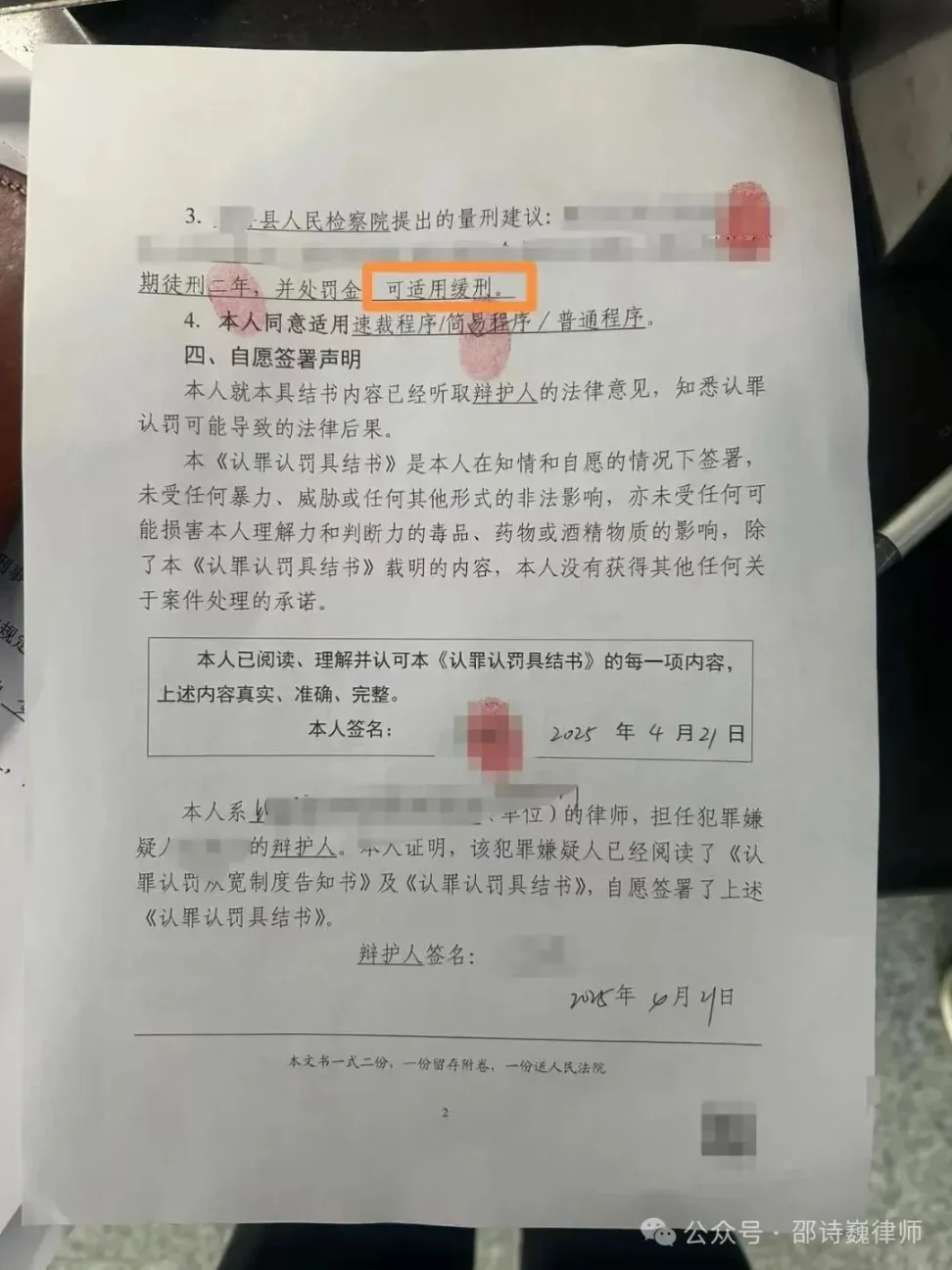

Ultimately, the sentencing recommendation dropped steadily—from the initial “at least seven or eight years,” to below five years, then to three years’ imprisonment, then suspended sentence of three years with a three-year probation, and finally settling at a result satisfying both me and the client: two years’ imprisonment, suspended with three years’ probation.

To outsiders, this might seem miraculous.

But for me, each adjustment, each persuasion, each communication rhythm followed my planned strategy. Due to length constraints, I’ll share more detailed tactics and dialogue with prosecutors another time.

When I finalized the result over the phone with the prosecutor, he said:

“The leadership agreeing to this outcome really reflects your legal work. Your defense was thorough and convincing—we acknowledge your arguments were sound.”

Honestly, after eight years of practice, this was the first time I’d heard such words from a prosecutor. As insiders know, while we speak of a “professional community,” genuine mutual respect between lawyers and case handlers remains rare.

The client was thrilled with the outcome and promptly signed the plea agreement. The case moved to court—but not without turbulence.

Shortly after filing, my colleague Attorney Ding received a call from the judge:

“How did the prosecution arrive at this sentencing recommendation? At most, it should be under five years—how could probation possibly apply?”

Our hearts sank. After all, the prosecution’s recommendation was merely advisory; the judge held final authority.

The twists and turns that followed aren’t worth detailing. In the end, the court adopted the prosecution’s recommendation: two years’ imprisonment, suspended with three years’ probation.

As a side note, the judge later quietly asked us: “How did you get the prosecutor to agree to this? They usually don’t even talk to us.” (His exact words.)

Reflection: Finding Hope in the Cracks

I often say criminal defense work is about finding hope in the cracks.

The successful outcome stemmed from meticulous litigation strategy and consistent, well-timed communication with case handlers. Every step required precise timing and careful judgment.

The case had clear charges, high amounts, and a client who admitted guilt and accepted factual allegations—including the figures provided by authorities. It appeared utterly hopeless. Yet I believe: as long as no final verdict has been issued, there is always room for negotiation and adjustment. The challenge isn’t denial, but identifying breakthrough points—leveraging the existing evidentiary framework to guide authorities toward a more favorable assessment.

The breakthrough here wasn’t challenging established facts, but accurately identifying the case handlers’ underlying concerns—finding the risks they found most unacceptable—and using those to shift the case outcome.

Throughout the defense, we didn’t downplay the severity, nor blindly challenge the charges. Instead, we designed a strategy focused on ensuring the case progressed smoothly while keeping punishment within a reasonable range. Ultimately, empathizing with the case handlers’ position and offering persuasive, well-grounded arguments was key to achieving a favorable result.

Gratitude for Peer Trust

This case came to me through a referral from Attorney Ding Yue of Shanghai SK Legal.

To be honest, over the years, many of my cases have come via peer referrals. But such trust isn’t easily earned—referrals represent professional endorsement. If the recommended lawyer fails, the referrer loses face. Especially in a complex, high-stakes case like this, it posed significant challenges for any attorney.

Yet Attorney Ding didn’t hesitate. She immediately recommended me, telling the family: “Attorney Shao has extensive experience with cryptocurrency and gambling-related cases. I hope he can join this defense.”

I was deeply moved. We’d never met, yet she sincerely recommended me without personal ties—placing the client’s interests above all.

Throughout the process, our collaboration was seamless—strategy discussions, family communication, document preparation—all perfectly coordinated. I also deeply respect her professionalism, sincerity, kindness, and unwavering responsibility toward clients and families.

Afterword

After finishing this piece, I’d like to add a few thoughts—not directly related to the case, but touching on the oft-repeated question: Why do lawyers defend the “guilty”?

Some might say: What’s there to defend? Gambling destroys families—these people deserve harsh punishment! Lawyers just help criminals escape justice, turning black into white!

But having handled hundreds of criminal cases, I’ve come to see that as criminal defense attorneys, we don’t face abstract “crimes”—we face real people, each carrying the weight of one or more families.

Even when someone’s actions are ultimately deemed criminal, there are often understandable reasons behind their choices.

In this case, the client had worked abroad for years seeking livelihood. An experienced crypto trader and skilled coder, he was introduced to “handling fund settlements for platforms.” It was a wrong decision—but his motivation was simple: to earn more money and provide a better life for his family.

While he did earn significantly over the past two years, he lived frugally. That’s why the funds in his exchange account remained largely untouched—only occasionally cashing out small amounts to send home for family expenses. The rest he saved for his child’s future education and living costs. He knew his illness might prevent him from seeing his child attend university—so he worked hard to leave something behind while still alive.

Yes, he broke the law and has already paid the price—detained for over half a year, surrendering illicit gains and paying fines. But if he were to remain imprisoned long-term, his family would fall into deeper crisis.

We never deny the harm of crime. But often, a defense lawyer isn’t just advocating for an accused individual—they’re helping save a family already on the brink of collapse. Perhaps this is one of the deepest meanings of criminal defense.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News