Class, Capital, and Trendy Toys: Decoding Pop Mart's Unreplicable Business Empire

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Class, Capital, and Trendy Toys: Decoding Pop Mart's Unreplicable Business Empire

Prejudice and misunderstanding are Pop Mart's致富经.

Author: Tastingo.eth/.sol Talin

On June 13, 2025, Pop Mart reached a market capitalization of $46 billion, with Wang Ning and his wife's combined wealth surpassing $20 billion, successfully entering the global billionaire top 100. All this was achieved rapidly within just two years, delivering investment returns far exceeding mainstream assets such as gold and Bitcoin.

As someone who has personally experienced the development of the designer toy industry since 2017, I’ve seen many popular science articles and analyses about Pop Mart—but most only scratch the surface, lacking genuine insight into real conditions.

This article will present another side of Pop Mart from the perspectives of capital and frontline operations. Thanks to all friends who liked and supported my work—your encouragement fuels my writing motivation. The views expressed here are based on insider observations and logical analysis of public information, which may contain biases and do not constitute investment advice. Copyright belongs to me and is exclusively published on X.com; unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited.

First, let me briefly share my journey in designer toys:

In 2016, shortly after graduation, I was working in venture capital. At that time, I noticed Pop Mart had opened stores in several Beijing commercial districts. But when I realized it was merely distributing the Japanese IP Sonny Angel, it didn’t leave a strong impression. In investor logic, only owning proprietary IPs truly unlocks expansive business potential.

Back then, the founder was obsessed with OFO, and I focused on hunting for sharing economy projects—thus missing Pop Mart entirely.

I didn’t pay attention again until late 2017, when Molly’s massive success drew my focus back—but by then it was too late.

By that point, Pop Mart had already received investments from multiple institutions, and its valuation was rising quickly. I shifted to pursuing the "second place"—52TOYS, which later went public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. At the end of 2017, I strongly advocated for our fund to invest in its Series A round at around 200 million RMB.

In 2019, I personally joined 52TOYS, responsible for signing and incubating designer IPs, serving over 500 designers, and leading or collaborating on exhibitions, e-commerce platforms, media matrices, and industry competitions. I was subsequently recommended by Qiming Venture Partners and successfully made the Forbes China 30 Under 30 list.

In 2021, with the rise of NFTs, I left to start my own company focused on NFT IP issuance. More details can be found on my personal website—I won’t elaborate further here.

As an industry practitioner, I once competed directly with Pop Mart at the designer level, vying for the same market attention and creative resources, accumulating substantial insider perspectives and hands-on experience. As a serial entrepreneur, I’m also accustomed to understanding business phenomena from the angles of entrepreneurs and capital operators.

TL;DR Summary

1) Pop Mart is a rare, non-replicable asset whose success required a uniquely supportive and patient environment—both in terms of capital availability and optimistic consumer sentiment—conditions unlikely to reappear today.

2) Pop Mart built its stores using a “luxury + Disney” model, binding designers and capturing user mindshare through an incubation mechanism, creating a high-error-tolerance moat. It’s not about individual IPs—it’s about the enduring strength of Pop Mart itself.

3) The ceiling moment for Pop Mart arrives when its audience expands so broadly that upper-class consumers reject it simply because “those people” now own it too. That’s when it stops being cool.

(I)

Pop Mart cannot be replicated—it emerged during China’s golden startup era defined by abundant liquidity, a period now irreversibly gone.

In winter 2010, Wang Ning arrived in Zhongguancun Ommi Center, Beijing, with 200,000 RMB earned from running variety stores in Zhengzhou, opening Pop Mart’s first physical store.

Initially, Pop Mart followed a Miniso-like retail model—selling a bit of everything. But this lack of focus meant users saw it merely as a general merchandise shop, resulting in weak brand premium, low profitability, cycles of expansion and contraction, and years of strategic trial and error.

If Wang Ning were starting today in 2025, he would likely have failed. Fortunately, between 2011 and 2014, several then-second-tier Chinese angel investors and VC firms became early backers, continuously funding him through experimentation. This allowed Wang Ning to open over ten quality stores, giving him crucial leverage in negotiations to secure exclusive distribution rights for Japanese designer toys in China during 2014–2015.

Pop Mart was a welcome surprise born from collaboration among second-tier domestic VCs of that era

Between 2015, Pop Mart’s distribution of the Japanese toy Sonny Angel exploded in popularity in China, accounting for over one-third of revenue.

Wang Ning and team finally recognized the power of combining this product category with their retail footprint—and decided to go all-in on designer toys.

But good times didn’t last. The Japanese partner soon revoked Pop Mart’s exclusive agency rights. This served as a wake-up call: relying on others’ IPs was unsustainable. They needed their own.

Wang Ning immediately posted a survey on Weibo: “Besides Sonny Angel, what other designer toys are you collecting?” Nearly half the replies mentioned “Molly.”

He flew to Hong Kong immediately to meet Kenny Wong, Molly’s creator, demonstrating unprecedented determination in “IP scouting.” At the time, few companies in the industry would fly out just to negotiate with a single artist. This sensitivity to “creator value” became the blueprint for all future IP operations at Pop Mart.

Early cooperation with Japanese IPs gave Pop Mart the confidence to fully commit to the designer toy space

Months later, the “Molly Zodiac” blind box series launched and sold out instantly, with hidden figures reselling for up to 10x on secondary markets. With Molly’s breakout success, Wang Ning realized owning IPs meant owning control. He aggressively signed artists like Pucky, Dimoo, Skullpanda, The Monsters, Bunny, and Yuki—each with distinct styles.

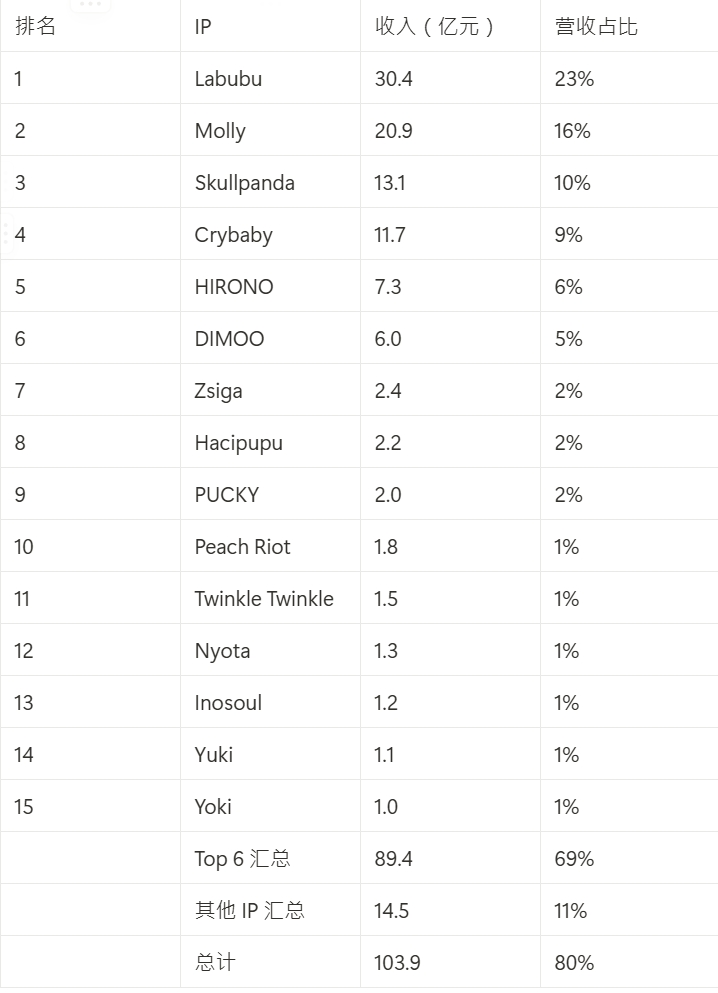

To date, Pop Mart has signed over 100 in-house designers. While top IPs rotate frequently, Pop Mart remains dominant, growing at lightning speed year after year.

The IP roster flows, but Pop Mart stands firm

Why could Wang Ning confidently shoulder 100% of the upfront costs (starting around 1–2 million RMB) for Molly’s blind box production and keep investing heavily in new designers?

Because he knew he could earn more → because market research revealed a viable Sonny Angel alternative → because he’d previously profited ~30 million RMB from Sonny Angel → because he had numerous stores ensuring sales and secured Japanese distribution rights → because despite repeated failures, he survived due to continuous support from patient capital and a growing base of willing consumers → because he operated in an era of abundant liquidity and sustained optimism.

Wang Ning might think I'm criticizing him by writing this. But I don't see it that way. On the contrary, consistently making sound strategic decisions grounded in business fundamentals is precisely what most founders lack—and this is Wang Ning’s strength. I've seen countless entrepreneurs squander excellent opportunities.

The pandemic in 2022 dealt Pop Mart a major blow, driving its stock price to a historic low. Patient capital and optimistic consumption sentiment vanished across the market. What no one—including myself—anticipated was that this environment would also completely destroy all competitors who hadn’t yet gone public but once harbored ambitions to replace Pop Mart.

Pop Mart thus became the undisputed leader, monopolizing the peak position in the designer toy industry. Why does capital race? Why must companies go public early? Pop Mart’s trajectory makes it clear.

After weathering the pandemic, Pop Mart leveraged its上市 cash reserves to aggressively expand overseas, achieving significant success in 2024—this time led by Labubu and Crybaby.

Crybaby (left), Labubu (right)

(II)

As the international expansion path becomes clearer, observers are recognizing the emergence of a new luxury model.

China has become a society where middle- and upper-class individuals widely consume luxury goods, propping up European luxury brands' valuations pre-pandemic. Even today, social media posts pairing “Labubu” most frequently appear alongside luxury items or limited-edition streetwear and footwear.

The Wang family clearly recognized this trend early. Their biggest strategic investments have consistently been in location selection, brand packaging, and store design—developing a unique aesthetic identity. Their stores sit at the intersection between luxury boutiques and Disney character merch shops, carving out a distinctive niche.

Pop Mart in France approaches the standard of luxury retail spaces

While others remained unaware before the pandemic, Wang Ning—the retailer at heart—had already cracked the growth flywheel:

Strong branding, prime locations, great products → high-end brand positioning and exposure → wealthy consumers begin noticing Pop Mart → limited and hidden editions gain value → blind boxes acquire financial/speculative attributes → regular consumers and scalpers enter the market → designers unlock wealth creation → talent meets demand → Pop Mart monopolizes top designer talent → affluent consumers reinforce spending

By the time others understood the game, the era had ended.

Many competitors attempted to challenge Pop Mart’s dominance but missed the core elements:

-

TOPTOY, under Miniso, opened decent stores but lacked taste in product curation and failed to secure exclusive access to top-tier designer talent

-

Finding Unicorn, backed by prominent VCs and featuring strong Korean IPs like FarmerBob, lacked the capability to open physical stores and couldn’t deliver the full experiential loop

-

Others like Coolfun Toys, AC TOYS, IP Station, and online players like Meichai each faced their own limitations.

TOPTOY spent heavily but failed to develop original hit IPs

In contrast, Alibaba’s KOITAKE (Jinli Naqu) achieved notable success with drama-themed blind boxes like “Empresses in the Palace”; 52TOYS strategically partnered with iconic IPs like Doraemon, Tom & Jerry, and pushed into male-oriented collectibles like Mighty Jaws, establishing solid footholds. Though far behind Pop Mart in overall IP influence, they continue steady growth by focusing on their strengths.

KOITAKE, under Alibaba Pictures, briefly gained viral fame with a “Country Love Story” blind box series

Monopoly breeds FOMO. Consequently, capital, affluent consumers, top designer talent, and prime retail locations increasingly concentrated around Pop Mart. Labubu’s overseas explosion was inevitable. With vast capital, superior site acquisition power, and deep IP reserves, Pop Mart simply waited for the right moment.

Lisa’s powerful collaboration officially brought Pop Mart into the global celebrity influencer circle. I don’t know how much Pop Mart paid Lisa’s team, but I believe she wouldn’t have delivered such a seamless, authentic partnership unless she genuinely loved the product. Without Pop Mart’s flagship stores in prime locations like Paris and Bangkok, such top-tier stars wouldn’t have taken notice.

Lisa enthusiastically promoted Labubu, sparking overseas buying frenzies

At this stage, even if Pop Mart releases no new IPs for three years, Labubu alone can sustain momentum long enough for the team to quietly identify and cultivate the next breakthrough character.

History proves Pop Mart’s consistent ability to discover new hits:

- Molly rose to prominence in 2016, though she’d existed for 10 years prior

- Skullpanda became a top performer in 2021, after flying under the radar for 3 years

- Labubu was crowned the new queen in 2024 (yes, Labubu is female), but she was signed in 2018—after her creator Long Jiasheng had nurtured the IP for another 3 years before that

The next Long Jiasheng will most likely sign with Pop Mart too, because the company has built something akin to a designer toy luxury empire. Without joining, creators can’t reach the wealthiest audiences.

So tell me—how could Pop Mart possibly lose?

(III)

Prejudice and misunderstanding are Pop Mart’s secret to wealth

Many people ask me: When should we short Pop Mart?

I say: Simple. The moment news about Pop Mart receives nothing but positive comments online, with zero criticism—that’s when it’s peaked.

Why does a designer toy IP typically stay hot for only 3–5 years? Because after that time, the rich realize their prized possessions are now owned by ordinary people who bought them secondhand at high prices. Subjectively, the elite refuse to accept that “those people” belong to their class. So they stop showcasing it—or abandon it altogether.

Once the upper class withdraws support, social media loses fresh content to fuel mass desire. In a forgetful world, attention shifts to the next trend—repeating the cycle endlessly.

Similarly, when Pop Mart gains universal acceptance across all demographics, the wealthy will de-fetishize it. Casual conversations will dismiss it with a shrug: “It’s not cool anymore.” That marks its death sentence.

It’s not that Pop Mart isn’t cool—it’s that it no longer offers the elite a sense of class superiority. There are no more dismissive remarks like “Can’t understand it—wouldn’t want it even if gifted!” to mock others with. When everyone loves Pop Mart, exclusivity vanishes. Then what’s left to love?

Finally, answering a few questions from readers:

1) Is it true Pop Mart has a secondary market maker team? What tactics do market makers use in the designer toy industry?

Yes! Especially in the early days, the key question is whether an IP can be strategically exposed to wider visibility, prompting discussion and collection within wealthy circles.

Key venues where the affluent gather: 1) Flagship stores in prime locations; 2) Annual large-scale exhibitions; 3) Fashion-influenced social circles. Hence you see long queues for limited signed editions, premium accounts on Xianyu (Idle Fish) showing豪spending to acquire rare pieces, and “toy whisperers” casually dropping hints at gatherings: “You haven’t heard of this figure? Really?”

To be honest, seeing someone like Aaron Kwok marry a woman from a “gold-digger training camp” reminds us how theatrical the world really is. We’re all human—no one is inherently superior. Just having more money means your brain gets washed just as easily.

2) I’m curious about how large-format items are sold. I only started following Pop Mart recently, but some second-generation wealthy friends (mostly nightlife crowd) were buying these things years ago. Back when most people still thought of them as blind boxes, they were already purchasing multi-thousand-dollar collector editions. Now their homes are filled with Labubus (and other brands’ IPs too). What drives their mindset?

You're referring to large-scale collectibles—limited releases often 1000% larger than standard blind boxes. These are typically part of a designer’s debut process. When a blind box version succeeds, it means the designer is already well-known. Blind box development is expensive, while small-batch large vinyl or resin figures are relatively cheaper and easier to produce.

For those embedded in various IP communities, getting early access to limited large-figure drops isn’t difficult. Similar to crypto, some insiders get early allocations, ride the hype, then sell these large figures for tens of times profit to collectors (“Bodhisattvas”). The next drop will be even better.

Their mindset? It’s play. If you enjoy designer toys and dive deep into the culture, that’s sufficient.

3) Compared to NFTs or meme coins, do designer toy market makers manipulate trading volume?

Yes, but it’s a supplementary tactic. Much simpler than NFTs. Teams batch-create accounts, trade controlled rare items at inflated prices to influence secondary market pricing for common figures. If prices deviate too much, they directly sweep floors to correct them. Since designer toys aren’t tokens, transactions lack transparency and verifiable records. From a recommendation algorithm perspective, it’s cheap to fabricate high transaction prices.

Still, this is auxiliary. If your product fails to catch the eye of the wealthy, no market-making effort will launch it, nor trigger mass distribution. Even if artificially pumped, disbelief persists until real trades expose the fraud. The IP may need to return to development, undergo continuous refinement and iteration, until it’s truly ready for full-scale deployment.

Otherwise, if mere market-making could create successful IPs, there would already be countless Labubus dominating the world, wouldn’t there?

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News