Analyzing RWA Tokenized Securities: A Horizontal Comparison of Global Regulatory Landscapes

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Analyzing RWA Tokenized Securities: A Horizontal Comparison of Global Regulatory Landscapes

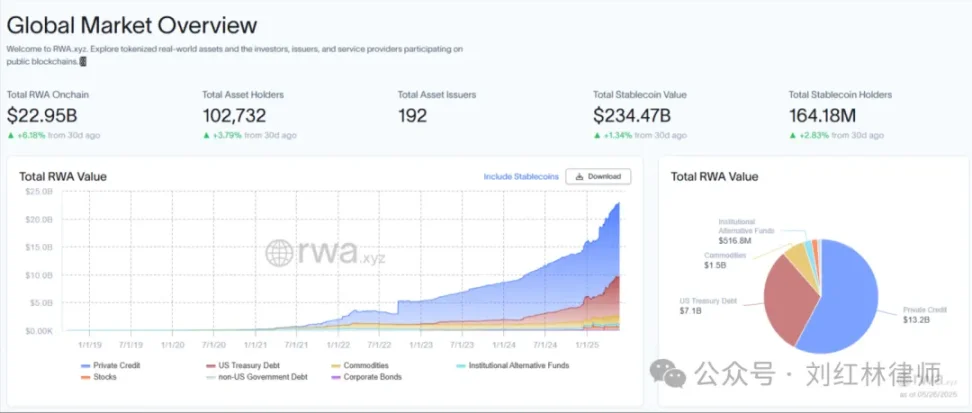

The Hong Kong stablecoin draft, the U.S. GENIUS proposal, and the adoption of MiCA in Europe and legislation in Southeast Asia undoubtedly represent significant progress for RWA applications.

Authors: Li Zhongzhen, Song Zeting

What is RWA?

RWA (Real World Assets) refers to the process of tokenizing real-world physical assets—such as real estate, gold, and artwork—or financial rights—including debt, revenue interests, fund shares—into digital tokens that can circulate on a blockchain. This innovative model enables asset divisibility, transparent ledgers, free transferability, and automated management. It relies technically on blockchain’s immutability and smart contracts’ automatic execution, while also requiring legal frameworks to ensure consistency between on-chain rights and underlying assets. In simple terms, RWA closely resembles traditional financial asset securitization but is more advanced and flexible.

For example, suppose you own a house worth 3 million yuan. To sell it in the traditional way, you might list it with real estate agents or platforms like Anjuke, spend time showing the property to multiple potential buyers, negotiate prices, and eventually find a buyer who must pay the full amount upfront. The transaction cycle is long and involves complex procedures. But if you tokenize this house using blockchain technology into a digital token called "house," dividing the ownership of the 3-million-yuan property into 30,000 house tokens—each valued at 100 yuan—then each token represents one-thirtieth-of-a-millionth ownership stake. Anyone could buy a fraction of the property for just 100 yuan and freely trade these tokens at any time—that's RWA.

However, we all know that in mainland China, changes in real estate ownership require formal title transfers at a real estate registration center. If such a house were actually tokenized and issued as house tokens on-chain, would owning a house token legally confer property rights? Clearly not—it directly conflicts with Chinese law.

In fact, the essence of RWA isn't moving the physical asset onto the blockchain (houses can't be moved, nor can equity), but rather tokenizing the “proof of ownership” — legal instruments such as stocks, bonds, or title deeds — converting them into on-chain tokens. That is, the nature of an asset is its “rights,” and those rights are embodied in “legally recognized documents.” What RWA does is repackage these legally protected instruments using blockchain technology to make their circulation more efficient and transparent—but only after the legal rights exist first, followed by the issuance of on-chain tokens.

Of course, from this perspective, the first step of RWA is tokenization—issuing RWA project tokens.

Securitization of RWA Tokens

(1) Classification of Tokens

To understand the securitization of RWA tokens, one must first grasp the classification of cryptocurrencies. However, since there is no globally unified standard among countries, regions, or organizations, cryptocurrency categorization remains fragmented. Below are current classifications across major jurisdictions:

1. Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission (SFC), jointly with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), classifies tokens into two categories: security tokens and non-security tokens. Security tokens are regulated under the Securities and Futures Ordinance, while non-security tokens fall under the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance.

2. Singapore

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) divides cryptocurrencies into three types: utility tokens, security tokens, and payment tokens. However, on March 27, 2025, MAS released a consultation paper titled *Consultation Paper on the Prudential Treatment of Cryptoasset Exposures and Requirements for Additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 Capital Instruments for Banks*, aiming to align cryptoasset classification with Basel standards.

3. United States

The U.S. classifies tokens as either commodities or securities, without further detailed distinctions. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has clearly categorized Bitcoin and Ethereum as commodities. Meanwhile, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) uses the Howey Test to determine whether an asset qualifies as a security. There is ongoing regulatory conflict between the SEC and CFTC over whether cryptocurrencies should be treated as "securities" or "commodities."

The Howey Test is the legal framework used by the SEC and courts to assess whether a transaction constitutes a "security"—specifically an "investment contract."

Under the Howey Test, a transaction is considered a security—and thus subject to U.S. securities laws—if it meets all four criteria:

a) An investment of money

b) In a common enterprise

c) With an expectation of profits

d) Derived from the efforts of others (e.g., promoters or third parties)

In 2019, the SEC ruled that Bitcoin did not meet the Howey Test. According to the ruling, Bitcoin only satisfies the first criterion—an investment of funds. However, because there is no central entity controlling Bitcoin, the SEC concluded it fails the other prongs: investors do not pool resources into a "common enterprise," and Bitcoin’s value does not rely on the efforts of a third party (such as developers).

4. European Union

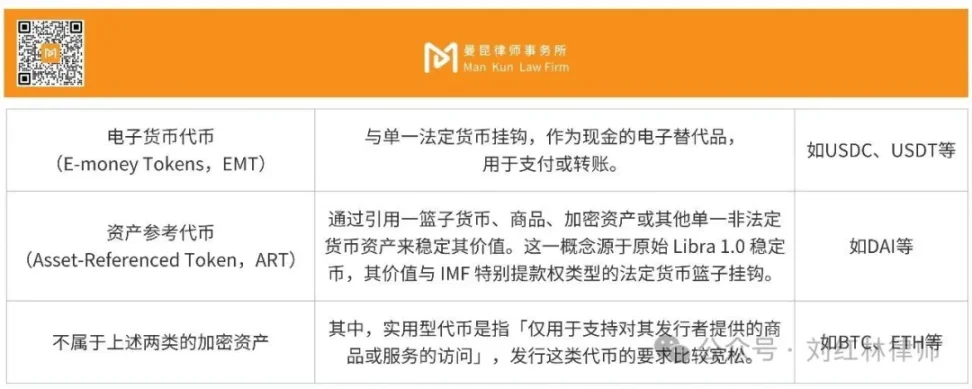

The EU’s Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation categorizes crypto-assets into electronic money tokens (EMTs), asset-referenced tokens (ARTs), and other crypto-assets. Notably, stablecoins commonly referred to in the market are split into EMTs and ARTs under MiCA.

5. Basel Committee

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) serves as the primary global standard-setter for prudential banking regulation and provides a platform for regular cooperation among regulators. Its 45 members represent central banks and supervisory authorities from 28 jurisdictions. The Basel Framework comprises a comprehensive set of standards adopted by BCBS members for application to internationally active banks within their jurisdictions. Under its SCO60 guidance on cryptoasset exposures, BCBS classifies cryptoassets into the following categories:

(2) Why Securitize RWA Tokens?

As previously noted, although there is no global consensus on token classification, most major jurisdictions—including Hong Kong, Singapore, and the U.S.—recognize the category of security tokens.

So, which category do RWA tokens belong to?

Actually, RWA token classification should depend on the nature of the underlying real-world asset:

-

A small portion of RWA tokens are non-security tokens. For instance, USDT and USDC—dominant players in the stablecoin market—are tokenized versions of fiat currency (the U.S. dollar). While they qualify as RWAs, they clearly do not constitute security tokens.

-

The majority of RWA tokens are security tokens. Take BlackRock’s tokenized fund BUIDL as an example: when investors contribute $1,000 to BUIDL, the fund promises each token maintains a stable value of $1 while generating returns through investment activities, offering yield to holders.

Given that most RWA tokens likely fall under the security token category, they must undergo securitization (i.e., be legally recognized as securities). This means such RWA tokens must comply with securities regulations in their respective markets. Failure to do so may result in severe consequences, ranging from heavy fines to criminal liability.

Global Regulatory Landscape for RWA Tokens

Currently, there are no specific regulations exclusively targeting RWA tokens. Since RWA tokens are fundamentally a form of cryptoasset, they are governed by existing regional cryptoasset regulations and legal frameworks.

(1) Hong Kong

Hong Kong formally passed its RWA stablecoin regulatory draft on May 21, 2025, outlining an eight-point compliance framework and regulatory approach for RWA-backed stablecoins:

1. Licensing system and entry thresholds

2. Reserve asset requirements

3. Transparency and information disclosure

4. Anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorism financing (CFT)

5. Legal enforcement powers of regulators

6. Cross-border coordination and enforcement authority

7. Investor protection mechanisms

8. Technological advancement and sustainable regulation

Under the Draft Stablecoin Ordinance, any entity engaging in fiat-backed stablecoin issuance, promotion, or related activities in Hong Kong must meet certain conditions—such as obtaining a license from the HKMA, meeting corporate qualification standards, demonstrating legitimate issuance purposes, conducting customer due diligence, implementing AML measures, and complying with ongoing supervision post-licensing. Potential tensions include balancing innovation with regulatory oversight. Overly stringent licensing requirements could stifle market innovation.

The reserve asset requirement emphasizes holding "high-quality, highly liquid assets," including cash, short-term government bonds, repurchase agreements, and near-cash equivalents. These assets share two core characteristics: low volatility and high liquidity, enabling quick conversion into cash during market stress or mass redemptions to maintain the stablecoin’s peg. Based on the Stored Value Facilities (SVF) license framework, licensed institutions must deposit a guarantee of HK$25 million or 5% of total assets, whichever is higher. By analogy, issuing a HK$10 billion stablecoin would require reserves ≥ HK$10 billion in fiat currency to ensure redeemability at par and mitigate bank-run risks.

Transparency and information disclosure are critical to market safety and confidence. In traditional finance, investor trust determines market efficiency and capacity. This explains why public companies must regularly disclose financial results (e.g., SEC filings like 10-K, 10-Q, 8-K, 13-F) and operational updates—to build investor confidence and ensure capital certainty and security.

The draft also addresses concerns about misuse: due to anonymity and cross-border mobility, stablecoins may be exploited for money laundering or terrorist financing. Therefore, targeted rules aim to ensure transparency and legality in transactions. Key safeguards include Know Your Customer (KYC) checks, traceability of funds, and recordkeeping. Hong Kong intends to align with international standards such as FATF’s *Guidance on Virtual Assets*. As long as reasonable transparency and privacy boundaries are maintained, these risks can be mitigated.

Additionally, the Draft Stablecoin Ordinance grants strong enforcement powers to the Monetary Authority. For example, if a stablecoin issuer is suspected of misappropriating reserves, the regulator can directly access financial records and transaction data. When necessary, it may appoint third parties (e.g., accounting firms) to assist investigations or even hire international experts to unravel cross-border money laundering networks.

In a globalized context, the ordinance establishes a worldwide regulatory network through cross-border coordination and robust enforcement. For instance, if an overseas stablecoin issuer is involved in money laundering, the HKMA can request assistance from local regulators (a practice sometimes dubbed “long-arm jurisdiction”). Through extraterritorial supervisory rights, emergency intervention powers, and cross-border applicability of civil and criminal sanctions, Hong Kong paves the way for globally compliant stablecoin operations.

In summary, the draft constructs a six-pillar investor protection “firewall” based on standardized准入 screening, risk isolation, transparent disclosures, tiered sales, rapid compensation, and strict penalties for violations. Its core logic includes:

-

Prior to launch: Strict issuer qualification controls to prevent fraud;

-

During operation: Mandatory transparency to deter manipulation;

-

Post-incident: Accessible remedies to reduce维权 costs.

This framework not only lays a solid foundation for Hong Kong’s stablecoin market but also sets a benchmark for global investor protection—embracing innovation while safeguarding retail investors from financial speculation. Serious violations such as unlicensed issuance, false advertising, or fraud will incur penalties including fines up to HK$5 million and seven years’ imprisonment, escalating to HK$10 million and ten years for aggravated cases.

Looking ahead, Hong Kong may explore embedding compliance rules directly into smart contracts, leveraging blockchain for automated regulation—meeting regulatory needs while preserving user privacy. Centered on “controllable risk and orderly innovation,” this approach injects compliance DNA into Hong Kong’s virtual asset ecosystem and contributes Eastern wisdom to global financial governance. While maintaining safety as a baseline, Hong Kong embraces fintech’s future with openness, aspiring to become a “super connector” in virtual asset regulation and innovation.

(2) U.S. GENIUS Act

On May 19, 2025, the U.S. Senate passed a procedural vote on the *Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act* (GENIUS Act), with 66 votes in favor and 32 opposed. The bill defines stablecoins precisely, specifies eligible issuers, and outlines issuance requirements—with particular emphasis on reserve adequacy.

The act mandates that all U.S.-compliant stablecoins must maintain 100% reserves matching the issued supply, held in cash, cash equivalents, or short-term bills and CDs. Reserves must undergo regular audits and public disclosures. Issuers have 18 months to adjust their liquidity structures to meet the new legal requirements. Currently, the USD1 stablecoin traded on exchanges operates in full compliance.

The GENIUS Act also indicates that algorithmic stablecoins will gradually phase out and some will be banned. Following the 2022 Terra/Luna collapse—which exposed fatal flaws and inherent instability in algorithmic models—the legislation calls for stricter controls to prevent recurrence. It strengthens anti-money laundering (AML) provisions, resolves conflict-of-interest issues, and prohibits U.S. government officials from issuing stablecoins. By providing legal legitimacy to Web3.0 and promoting sustained public education, the act aims to reduce fraud, money laundering, and cybersecurity threats.

(3) Singapore

On January 14, 2019, Singapore enacted the *Payment Services Act 2019 (PSA)*, subsequently amended to serve as a forward-looking and flexible framework regulating payment systems and service providers. It replaced the former *Payment Systems (Oversight) Act* and *Money-changing and Remittance Businesses Act*. Additionally, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) issued Notice PSN01 (*Prevention of Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism – Designated Payment Services*) under the PSA, imposing AML/CFT obligations on regulated payment service providers. Compliance requires the following measures:

-

Risk assessment and mitigation

-

Customer due diligence

-

Reliance on third parties

-

Correspondent accounts and wire transfers

-

Record keeping

-

Suspicious transaction reporting

-

Internal policies, compliance, auditing, and training

On March 27, 2025, MAS published a consultation paper titled *Consultation Paper on the Prudential Treatment of Cryptoasset Exposures and Requirements for Additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 Capital Instruments for Banks*, aiming to implement updated prudential standards from the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) regarding cryptoasset risks. It proposes classifying qualifying cryptoassets into Group 1a (tokenized versions of traditional assets) or Group 1b (cryptoassets designed to maintain a stable value linked to predefined reference assets via effective stabilization mechanisms).

For Group 1b cryptoassets, BCBS prescribes a redemption risk test to ensure reserves are sufficient to allow redemption at face value at any time. To pass this test, banks must verify that reserve assets meet requirements concerning value, composition, and asset management practices.

(4) European Union

In June 2023, the EU officially launched the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA), which regulates two main categories:

1) Crypto-asset issuers, including stablecoin issuers and other crypto-asset issuers.

MiCA imposes the following key requirements on stablecoin issuers:

-

Authorization prior to issuance

-

Fulfillment of disclosure obligations

-

Maintenance of minimum own funds and adequate reserve assets

Requirements for other crypto-asset issuers are relatively lighter:

-

Must establish a legal entity within the EU

-

Publication of a whitepaper

2) Crypto-asset service providers (CASPs). MiCA sets four main requirements for CASPs:

-

Licensing/authorization

-

Sound governance structure

-

Minimum capital requirements

-

Consumer protection and transparency obligations

Beyond Law: Underlying Challenges in RWA Practice

The passage of Hong Kong’s stablecoin draft, the U.S. GENIUS Act, the EU’s MiCA, and Southeast Asian legislation marks significant progress for RWA applications. Yet beyond regulation, several latent challenges remain unresolved by legal frameworks alone—such as RWA liquidity on centralized exchanges and Web3 anti-fraud education. These are less weaknesses of RWA than uncertainties inherent in early-stage innovation, solvable only over time.

While attention focuses on legal refinement, RWA faces multiple hidden hurdles in practice—its development path resembling a marathon more than a sprint.

(1) Liquidity Dilemma: The 'False Promise' of Centralized Platforms

Currently, RWA tokens exhibit stark liquidity polarization between centralized exchanges (CEXs) and their underlying assets in traditional financial markets. In Hong Kong, despite accelerating license approvals attracting institutional capital, certain funds—like BlackRock’s BUIDL treasury token—still suffer from visibly inadequate daily liquidity. This theory-practice gap stems from the heterogeneity of RWA assets themselves: securitized tokens require a nascent and complex custody-clearing infrastructure. More critically, the liquidity premium mechanism prevalent in traditional finance has yet to fully migrate on-chain. Identical real estate assets may be double-pledged across multiple platforms, while delays in synchronizing off-chain registries with public blockchain data hinder arbitrageurs from closing price gaps.

(2) Education Gap: Cognitive Misalignment Between Web3 Natives and the Real World

Anti-fraud education proves far more complex than basic risk warnings. Even in jurisdictions where RWA is legal, misconceptions persist. For example, some Web3 users in Singapore mistakenly view “RWA” as a new type of stablecoin, while European pension fund investors compare RWA tokenized bonds directly with traditional ABS yields. Such cognitive mismatches enable novel fraud schemes. One project, for instance, forged government digital signatures to market its bond as a “central bank-endorsed” RWA token, illegally raising funds on decentralized forums. Standardized disclosure templates mandated by regulators struggle to address such technically targeted deceptions.

(3) Technical Debt: Underestimated Off-Chain–On-Chain Coordination Costs

Most existing RWA solutions fall into the “oracle paradox.” For example, when a trust uses Chainlink oracles to report rental income, node operators may demand both offline and on-chain audit reports. This hybrid architecture leads to rising marginal costs. A European railway asset tokenization project was forced to delay the migration of €800 million in assets due to security disputes over a Polkadot-Cosmos cross-chain bridge. These friction points introduce wear and risk absent in traditional finance. Given such complexity and higher overhead compared to legacy systems, what incentives or solutions could drive broader adoption of RWA token systems?

Resolving these deep-seated contradictions demands solutions beyond pure technology or regulation. On liquidity, a dual-track “custody + oracle” model could allow traditional custodians to issue digital ownership certificates on-chain, as exemplified by Ondo Finance and its product suite. For education, Cyberport Hong Kong has launched an RWA sandbox simulator using gamified interfaces to demonstrate end-to-end risk points in asset tokenization. The true maturation of RWA may give rise to a “third infrastructure” bridging traditional finance and crypto-native ecosystems. As markets eagerly anticipate milestones like the $50 billion RWA market cap, greater attention should be paid to invisible costs excluded from financial statements. These undercurrents remind us that RWA’s pace of evolution ultimately hinges on how efficiently the real world integrates with digital-native systems—a long-term game demanding patience and wisdom.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News