Salt Tickets and Bitcoin, A Game of Power

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Salt Tickets and Bitcoin, A Game of Power

The contest between state and market is a clash of credibility, a struggle for institutional supremacy.

By Liu Honglin

The Summer of Yanchi

That summer in the 42nd year of Qianlong, the surface of Yuncheng's salt lake had lost its usual emerald hue. Layer upon layer of blinding salt crust lay exposed, as if the earth had shed its old skin beneath the scorching sun.

Cao Dehai stood at the gate of the salt yard, watching workers carry baskets of salt into storage. Yet his heart felt as dry as the cracked lakebed. Tomorrow was the day the Salt Transport Office would come to collect the salt tax. Without that half-foot-long salt ticket, all his stored salt was nothing but contraband—unable to pass checkpoints, unable to leave Yuncheng.

In the world of the salt lakes, a salt ticket was a pass, a key to wealth, and also the government’s chain. Made of hemp paper and stamped with the crimson seal of the Hedong Salt Transport Office, inscribed on the back with merchant name, ticket number, and tax payment, it seemed light in hand but determined a salt merchant’s survival for the entire year.

Historical records show that Yuncheng’s salt lake produced nearly five million dan of salt annually, accounting for about one-tenth of the nation’s total output. The salt tax from Hedong contributed thirty percent of Shanxi Province’s fiscal revenue (Volume V, *Collected Historical Materials on Qing Dynasty Salt Administration*). The salt from this lake was not merely seasoning on people’s dining tables—it funded military payrolls and sustained the empire’s very lifeline.

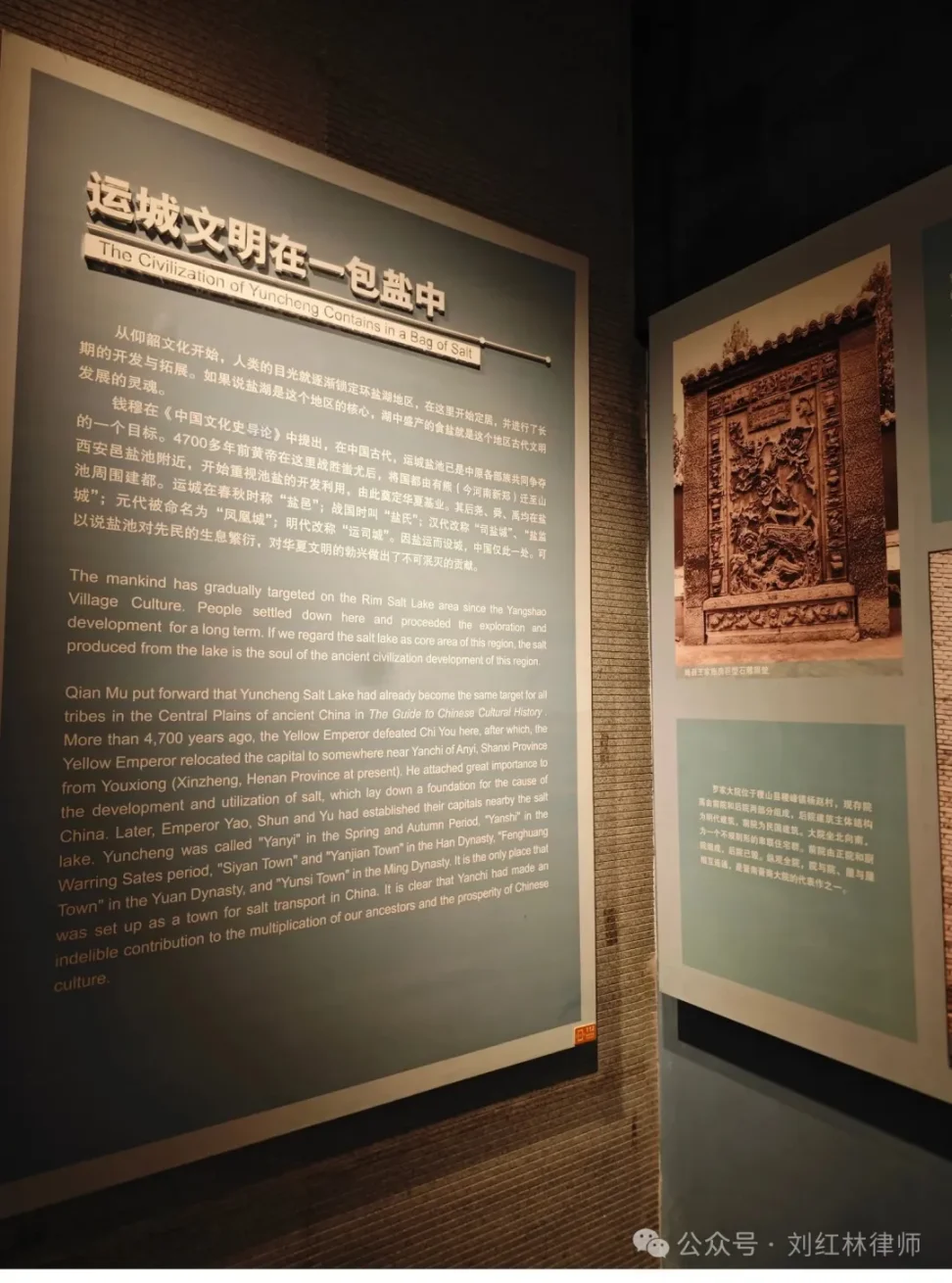

Qian Mu wrote in *An Introduction to Chinese Cultural History*: "The Yuncheng salt lake had already become a shared target of contention among various tribes in central China." Over 4,700 years ago, after defeating Chiyou, the Yellow Emperor moved his capital near Anyi’s salt lake, initiating the development and utilization of lake salt and laying the first cornerstone of Chinese civilization. Yao, Shun, and Yu later established their capitals here. During the Spring and Autumn period it was called "Yanyi," in the Warring States era "Yanshi," during the Han dynasty "Siyancheng" or "Yanjiancheng," in the Yuan dynasty "Fenghuangcheng," and in the Ming dynasty "Yunsicheng." A city built around salt transport—this is unique in all of China.

Cao Dehai remembered his father’s final words: "We’re not in the salt business—we’re in the salt ticket business. Without the ticket, carrying salt is like carrying knives."

Salt Merchants and the Trade in Salt Tickets

The origin of the salt ticket traces back to the "Kai Zhong System" of the early Ming dynasty. From that time onward, the state held tightly in its grasp the wealth of the salt lakes through a single piece of paper.

The salt ticket served both as a circulation permit and as a receipt for imperial salt taxes—a vital artery of state finance. Yet during the Qianlong era, with the rise of native banks and flourishing postal roads, the nature of the salt ticket quietly shifted: no longer merely a voucher for salt redemption, it became an object of trade among merchants.

Salt merchants learned a new game: obtain a ticket, then resell it instead of redeeming the salt immediately, profiting from the price difference. Through flipping, consolidating, and transferring tickets, these slips changed hands in teahouses and taverns, evolving into a kind of gray-market "financial instrument."

*Collected Historical Materials on Qing Dynasty Salt Administration* records: "The practice of ticket speculation has deepened over time, leading even to exchanges between silver notes and salt tickets, resulting in repeated losses of government tax revenue." The salt ticket—originally a tool for state control—grew side branches within market gaps. In the 37th year of Qianlong, a major scandal erupted over ticket speculation at Yuncheng’s salt lake, implicating even officials from the Salt Transport Office. One memorial stated: "The ticket-flipping case involved dozens of officials and hundreds of merchants; salt tax collection collapsed, and treasury silver ran short." (*Selected Archives on Qing Dynasty Salt Policy*, Volume 32)

But the government never stopped calculating.

Speculation disrupted the market, yet it also became a lubricant for public finances. The "handling fees" from ticket trades and kickbacks to officials turned into hidden sources of local salt revenue. In a memorial submitted in the 42nd year of Qianlong, the Hedong Salt Intendant wrote: "Though ticket speculation is a malpractice, tax revenues can still be collected. Strict prohibition might cause a complete halt, risking the discontinuation of salt tickets altogether."

Thus, under the red seal of the salt ticket, the state and the market repeatedly tested each other. The state used salt tickets to sustain military funding and bureaucratic operations; salt merchants used flipping and consolidation to turn red slips into flowing silver. The credit of the salt ticket ultimately rested on the authority of official seals and the presence of salt police—but market forces always found ways to slip through the cracks of that authority.

Those porters and bankers caught between the folds of the system perhaps understood best: in this world, there has never been pure freedom, nor absolute prohibition.

The Co-opted Cryptocurrency

Some say cryptocurrency is decentralized—the ultimate challenge to national monetary sovereignty. Algorithmic consensus, distributed ledgers, anonymous wallets—these seem to have freed wealth from the chains of the state, letting it flow freely like the wind across the salt lakes.

Yet history has already written the answer. Ticket speculation was once seen as a disease undermining state monopoly, yet ended up becoming a lubricant in the government’s books. The red stamp on the salt ticket was both restriction and permission. Behind every ideal of decentralization, the state’s touch and shadow remain.

People once believed cryptocurrency was the final challenge to state-issued money. But today, embracing regulation has become the dominant theme. KYC, AML, exchange compliance, tax transparency—these terms drift like salt crystals in the wind, layering over the word "decentralized."

The state’s calculations always find a way to absorb ideals of freedom into institutional frameworks.

In 2025, at the Bitcoin Conference, U.S. Vice President Vance spoke bluntly: "Bitcoin is a tool to fight bad policy, regardless of which party makes it. China doesn’t like Bitcoin… Since China is stepping away from Bitcoin, perhaps America should step toward it. We’ve established a National Bitcoin Reserve, making Bitcoin a strategic asset for the U.S. government. Dollar-backed stablecoins won’t weaken the dollar—they’ll be force multipliers of American economic power."

Just as the salt ticket once controlled the flow of salt through red stamps and bureaucratic pen, today’s regulators use compliance licenses and blockchain monitoring to hold the direction of wealth in their digital fingertips. The state may have lost its monopoly on paper notes, but through laws, licenses, and on-chain surveillance, it has rebuilt an invisible wall. Regulatory hands now reach into every wallet address; the openness of blockchain data has ironically become the state’s new weapon.

The state’s grip on the reins of wealth has never truly loosened.

The Game of Power

The story of the salt lake has faded into the past; salt tickets are now yellowed pages in history books. Yet on those aging sheets of hemp paper, traces of collusion between state and market remain visible. The flow of wealth has never been mere commodity exchange—it is always a博弈 between state and market, a contest of credibility, a play of institutional power.

The credit of the salt ticket ultimately rested on state authority; the credit of cryptocurrency, though seemingly decentralized, still lingers in the shadow of national law. Without regulatory approval, without tax channels, no matter how many nodes a cryptocurrency has, it can only drift in the liminal space between gray and white.

Standing by the edge of Yuncheng’s salt lake, gazing at the layers of dried salt crust, I seem to see the true color of wealth: half the desire of the market, half the枷锁 of institutions. Salt tickets, paper money, Bitcoin—their forms change, but the essence of power remains unchanged.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News