Viewing the Technological Competition Between FHE, TEE, ZKP, and MPC Through Sui's Sub-Second MPC Network lka

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Viewing the Technological Competition Between FHE, TEE, ZKP, and MPC Through Sui's Sub-Second MPC Network lka

From a functional perspective, Ika is building a new security verification layer: serving as a dedicated signing protocol for the Sui ecosystem while also providing standardized cross-chain solutions for the entire industry.

Author: YBB Capital Researcher Ac-Core

1. Ika Network Overview and Positioning

Image source: Ika

The Ika network, receiving strategic support from the Sui Foundation, has recently unveiled its technical positioning and development direction. As an innovative infrastructure based on multi-party computation (MPC) technology, its most notable feature is sub-second response speed—an unprecedented achievement among peer MPC solutions. Ika’s compatibility with the Sui blockchain is particularly strong, as both share highly aligned foundational design principles such as parallel processing and decentralized architecture. In the future, Ika will be directly integrated into Sui’s developer ecosystem, offering plug-and-play cross-chain security modules for Sui Move smart contracts.

In terms of functional positioning, Ika is building a new security verification layer—acting both as a dedicated signature protocol for the Sui ecosystem and providing standardized cross-chain solutions across industries. Its layered design balances protocol flexibility with development convenience, making it a likely candidate to become a significant case study for large-scale MPC adoption in multi-chain scenarios.

1.1 Core Technology Breakdown

Ika's technical implementation centers on high-performance distributed signing. Its innovation lies in combining a 2PC-MPC threshold signature protocol with Sui’s parallel execution and DAG consensus, achieving true sub-second signing speeds while enabling large-scale decentralized node participation. By integrating 2PC-MPC, parallelized distributed signing, and tight alignment with Sui’s consensus structure, Ika aims to build a multi-signature network that simultaneously meets extreme performance and rigorous security demands. The core innovation involves introducing broadcast communication and parallel processing into threshold signature protocols. Below is a breakdown of key functionalities.

2PC-MPC Signature Protocol: Ika adopts an improved two-party MPC scheme (2PC-MPC), effectively splitting user private key signing operations between two roles: the “user” and the “Ika network.” This transforms the traditionally complex pairwise node communication process (similar to everyone in a group chat messaging each other individually) into a broadcast model (like a group announcement). As a result, computational and communication overhead for users remains constant regardless of network size, keeping signature latency within sub-second ranges.

Parallel Processing – Splitting Tasks for Simultaneous Execution: Leveraging parallel computing, Ika breaks down each signing operation into multiple concurrent subtasks executed simultaneously across nodes to dramatically increase speed. This approach integrates Sui’s object-centric parallel model, eliminating the need for global transaction ordering consensus. Multiple transactions can be processed concurrently, boosting throughput and reducing latency. Sui’s Mysticeti consensus uses a DAG structure to eliminate block confirmation delays, allowing immediate block submission, which enables Ika to achieve sub-second finality on Sui.

Large-Scale Node Network: Traditional MPC schemes typically support only 4–8 nodes, whereas Ika scales to thousands of nodes participating in signing. Each node holds only a fragment of the private key; even if some nodes are compromised, the full private key cannot be reconstructed. A valid signature can only be generated when both the user and network nodes participate together—neither party alone can operate or forge signatures. This distributed node model is central to Ika’s zero-trust architecture.

Cross-Chain Control and Chain Abstraction: As a modular signature network, Ika allows smart contracts on other chains to directly control accounts within the Ika network (called dWallets). For example, if a smart contract on another chain (e.g., Sui) needs to manage a multi-signature account on Ika, it must first verify the state of that chain within the Ika network. Ika achieves this by deploying lightweight clients (state proofs) of the respective chains on its own network. Currently, Sui state proofs have been implemented first, enabling Sui-based contracts to embed dWallets into their business logic and use the Ika network to sign and operate assets on other chains.

1.2 Can Ika Empower the Sui Ecosystem in Return?

Image source: Ika

After launch, Ika could expand the capability boundaries of the Sui blockchain and provide infrastructural support to the broader Sui ecosystem. Sui’s native token SUI and Ika’s token $IKA will work in tandem, with $IKA used to pay for Ika network signing services and serve as staking collateral for nodes.

Ika’s greatest impact on the Sui ecosystem is bringing cross-chain interoperability. Its MPC network enables assets from chains like Bitcoin and Ethereum to be connected to Sui with low latency and high security, facilitating cross-chain DeFi operations such as liquidity mining and lending, thereby enhancing Sui’s competitiveness in this area. Due to its fast confirmation speed and strong scalability, Ika has already been adopted by several Sui projects, contributing to ecosystem growth.

In terms of asset security, Ika offers a decentralized custody mechanism. Users and institutions can manage on-chain assets via its multi-signature approach, which is more flexible and secure than traditional centralized custodianship. Even off-chain transaction requests can be securely executed on Sui.

Ika also introduces a chain abstraction layer, enabling Sui smart contracts to directly operate accounts and assets on other chains without going through cumbersome bridging or asset wrapping processes—significantly simplifying cross-chain interactions. Native Bitcoin integration further allows BTC to directly participate in DeFi and custody operations on Sui.

Lastly, Ika provides a multi-party validation mechanism for AI automation applications, preventing unauthorized asset operations and improving the security and trustworthiness of AI-driven transactions, potentially paving the way for Sui’s future expansion into AI.

1.3 Challenges Facing Ika

Although Ika is tightly coupled with Sui, to become a “universal standard” for cross-chain interoperability, it must gain acceptance from other blockchains and projects. The market already hosts numerous cross-chain solutions such as Axelar and LayerZero, widely used in different scenarios. For Ika to stand out, it must strike a better balance between “decentralization” and “performance” to attract more developers and encourage greater asset migration.

MPC itself also faces ongoing controversy, particularly around the difficulty of revoking signing permissions. Like traditional MPC wallets, once a private key is split and distributed, even after re-sharding, those holding old fragments might theoretically still reconstruct the original private key. Although the 2PC-MPC model enhances security by requiring continuous user participation, there remains no fully mature mechanism for securely and efficiently replacing nodes—a potential risk factor.

Ika also depends heavily on the stability of the Sui network and its own operational health. If Sui undergoes major upgrades—such as updating its Mysticeti consensus to MVs2—Ika will need to adapt accordingly. While Mysticeti’s DAG-based consensus supports high concurrency and low fees, the lack of a mainchain structure may complicate network paths and make transaction ordering harder. Additionally, being asynchronous, it brings new challenges in transaction sorting and consensus security. Moreover, the DAG model strongly relies on active user participation; low network usage can lead to delayed confirmations and reduced security.

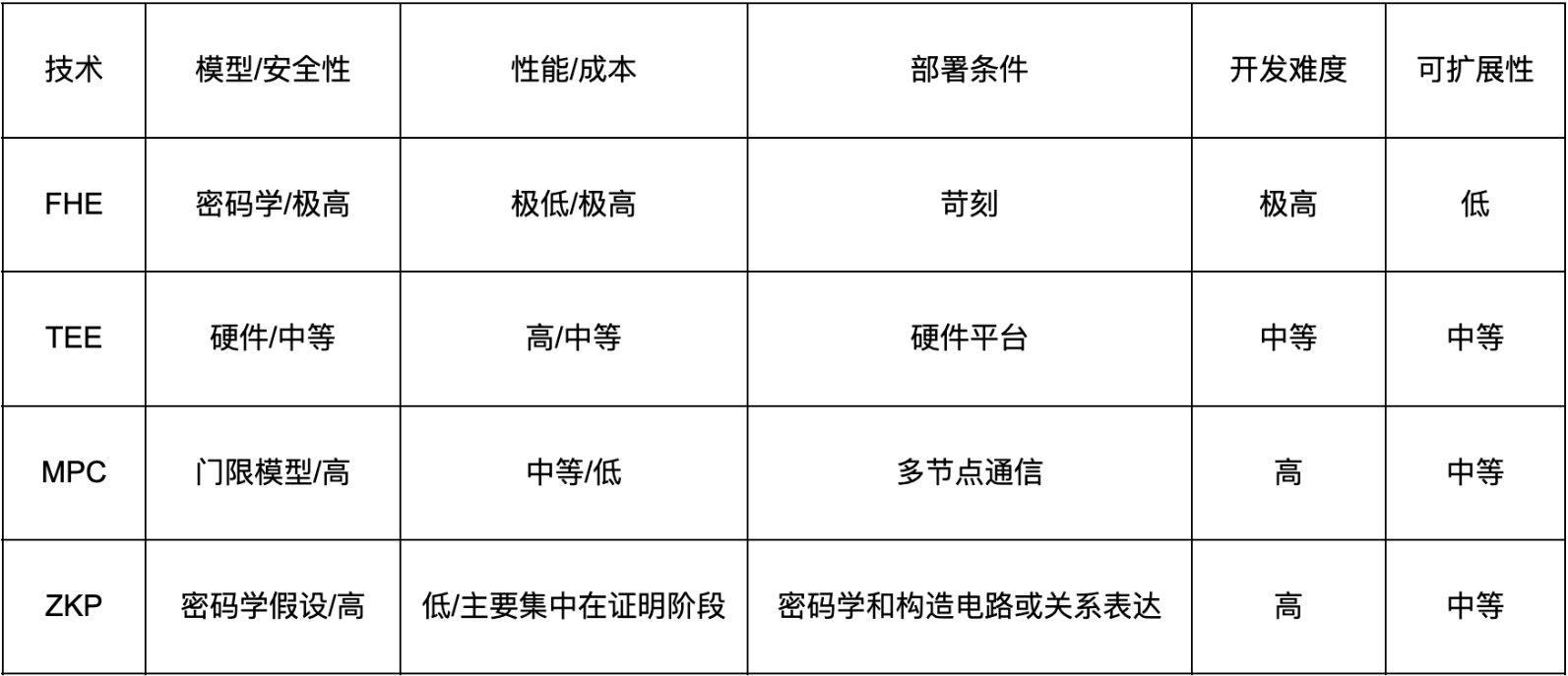

2. Comparison of Projects Based on FHE, TEE, ZKP, or MPC

2.1 FHE

Zama & Concrete: Beyond a general-purpose compiler based on MLIR, Concrete employs a “layered bootstrapping” strategy, breaking large circuits into smaller encrypted segments and dynamically stitching results, significantly reducing per-bootstrapping latency. It also supports “hybrid encoding”—using CRT encoding for latency-sensitive integer operations and bit-level encoding for highly parallel Boolean operations—balancing performance and parallelism. Additionally, Concrete features a “key packing” mechanism, allowing multiple homomorphic operations after a single key import, reducing communication overhead.

Fhenix: Built on TFHE, Fhenix includes custom optimizations tailored for the Ethereum EVM instruction set. It replaces plaintext registers with “ciphertext virtual registers,” automatically inserting micro-bootstrapping operations before and after arithmetic instructions to restore noise budgets. Fhenix also includes an off-chain oracle bridge module that checks proofs before interacting with on-chain ciphertext states and off-chain plaintext data, reducing on-chain verification costs. Compared to Zama, Fhenix emphasizes EVM compatibility and seamless integration with on-chain contracts.

2.2 TEE

Oasis Network: Building on Intel SGX, Oasis introduces a “layered root of trust,” using the SGX Quoting Service at the hardware level to verify authenticity, a lightweight microkernel at the mid-layer to isolate suspicious instructions and reduce SGX side-channel attack surfaces. ParaTime interfaces use Cap’n Proto binary serialization for efficient cross-ParaTime communication. Additionally, Oasis developed a “durability log” module that records critical state changes into trusted logs to prevent rollback attacks.

2.3 ZKP

Aztec: Beyond Noir compilation, Aztec incorporates “incremental recursion” in proof generation, recursively bundling multiple transaction proofs over time and generating a single compact SNARK. The proof generator uses a Rust-written, parallelized depth-first search algorithm, achieving linear acceleration on multi-core CPUs. To reduce user wait times, Aztec offers a “light node mode,” where nodes download and verify only zkStreams instead of full proofs, further optimizing bandwidth usage.

2.4 MPC

Partisia Blockchain: Its MPC implementation extends the SPDZ protocol, adding a “preprocessing module” that generates Beaver triples off-chain to accelerate online computation. Nodes within each shard communicate via gRPC over TLS 1.3 encrypted channels, ensuring secure data transmission. Partisia’s parallel sharding mechanism also supports dynamic load balancing, adjusting shard sizes in real-time based on node load.

3. Privacy Computing: FHE, TEE, ZKP, and MPC

Image source: @tpcventures

3.1 Overview of Different Privacy Computing Approaches

Privacy computing is a hot topic in blockchain and data security, with major technologies including Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE), Trusted Execution Environments (TEE), and Multi-Party Computation (MPC).

● Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE): An encryption scheme allowing arbitrary computations on encrypted data without decryption, keeping inputs, computations, and outputs fully encrypted. Security is based on complex mathematical problems (e.g., lattice problems), offering theoretically complete computational capability, but at extremely high computational cost. Recently, industry and academia have improved performance through algorithm optimization, specialized libraries (e.g., Zama’s TFHE-rs, Concrete), and hardware acceleration (Intel HEXL, FPGA/ASIC), though FHE remains a “slow but powerful” technology.

● Trusted Execution Environment (TEE): A trusted hardware module provided by processors (e.g., Intel SGX, AMD SEV, ARM TrustZone) that runs code in an isolated secure memory area, shielding execution data and state from external software and the operating system. TEE relies on hardware roots of trust, delivers near-native performance with minimal overhead, and provides confidential execution. However, its security depends on hardware implementation and firmware provided by manufacturers, posing risks of backdoors and side-channel attacks.

● Multi-Party Computation (MPC): A cryptographic protocol enabling multiple parties to jointly compute a function without revealing their private inputs. MPC eliminates single-point hardware trust but requires extensive interaction among participants, resulting in high communication overhead and performance constrained by network latency and bandwidth. Compared to FHE, MPC incurs much lower computational costs, though it is complex to implement and requires careful protocol and architectural design.

● Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP): A cryptographic technique allowing one party to prove the truth of a statement to another without revealing any additional information. A prover can convince a verifier they know a secret (e.g., a password) without disclosing it. Common implementations include elliptic curve-based zk-SNARKs and hash-based zk-STARKs.

3.2 What Are the Suitable Applications for FHE, TEE, ZKP, and MPC?

Image source: biblicalscienceinstitute

Different privacy computing technologies emphasize different strengths—the choice depends on specific application needs. Take cross-chain signing: it requires collaboration among multiple parties and avoids exposing a single private key, making MPC particularly practical. Threshold signatures, for instance, involve multiple nodes each holding a portion of the key, collectively signing so no individual controls the full private key. More advanced approaches, like Ika’s network, treat the user as one party and system nodes as another, using 2PC-MPC for parallel signing—capable of handling thousands of signatures simultaneously and scaling horizontally with more nodes increasing speed. TEE can also perform cross-chain signing by running signing logic inside an SGX chip, offering fast speed and easy deployment. However, if the hardware is compromised, the private key is exposed, placing full trust in the chip and manufacturer. FHE performs poorly here because signing doesn’t align well with its strength in “addition and multiplication” operations—while theoretically possible, the overhead is too great for practical use in real systems.

In DeFi scenarios like multi-sig wallets, treasury vaults, and institutional custody, multi-sig is inherently secure, but the challenge lies in how to store private keys and distribute signing risk. MPC is now the mainstream approach—service providers like Fireblocks split signatures across nodes so that no single breach compromises the entire key. Ika’s design is also interesting: its two-party model ensures “non-collusion” of private keys, reducing the risk of all parties conspiring maliciously, a known weakness in traditional MPC. TEE is also used here, such as in hardware or cloud wallets leveraging trusted environments to isolate signing operations, though it still hinges on hardware trust. FHE currently plays little direct role in custody, being more relevant to protecting transaction details and contract logic—for example, enabling private transactions where amounts and addresses remain hidden. But this doesn’t directly relate to private key custody. Thus, in this context, MPC focuses on decentralizing trust, TEE emphasizes performance, and FHE applies primarily to higher-level privacy logic.

In AI and data privacy, the situation differs. Here, FHE’s advantages become clearer. It allows data to remain encrypted end-to-end—for instance, uploading medical data for AI inference, where FHE enables models to make judgments without seeing plaintext, outputting only encrypted results. This “computation on encrypted data” capability is ideal for sensitive data processing, especially in cross-chain or inter-institutional collaborations. Mind Network, for example, explores letting PoS nodes use FHE to validate votes without knowing others’ choices, preventing vote copying and ensuring privacy. MPC can also enable federated learning—multiple institutions train models collaboratively while keeping local data private, exchanging only intermediate results. But as participant numbers grow, communication costs and synchronization become bottlenecks, limiting current use mostly to experimental projects. TEE can run models directly in protected environments and is used in some federated learning platforms for model aggregation, but faces constraints like limited memory and side-channel vulnerabilities. Hence, in AI-related use cases, FHE’s “end-to-end encryption” stands out, while MPC and TEE serve as auxiliary tools requiring tailored integration.

3.3 Differences Among the Approaches

Performance and Latency: FHE (Zama/Fhenix) suffers from high latency due to frequent bootstrapping, yet offers the strongest data protection under encryption; TEE (Oasis) has the lowest latency, close to normal execution, but requires hardware trust; ZKP (Aztec) maintains controllable latency in batch proofs, with individual transaction delay between the two; MPC (Partisia) has medium-to-low latency, most affected by network communication.

Trust Assumptions: FHE and ZKP rely on mathematical hardness assumptions, requiring no third-party trust; TEE depends on hardware and manufacturers, vulnerable to firmware exploits; MPC assumes semi-honest behavior or at most t faulty parties, sensitive to assumptions about participant count and behavior.

Scalability: ZKP rollups (Aztec) and MPC sharding (Partisia) naturally support horizontal scaling; FHE and TEE scaling depend on computational resources and hardware node availability.

Integration Difficulty: TEE has the lowest entry barrier, requiring minimal changes to programming models; ZKP and FHE require specialized circuits and compilation flows; MPC demands protocol stack integration and cross-node communication setup.

4. Market Perception: Is “FHE Superior to TEE, ZKP, or MPC”?

It appears that whether FHE, TEE, ZKP, or MPC, all face a kind of impossibility triangle in real-world applications: “performance, cost, security.” While FHE offers compelling theoretical privacy guarantees, it does not outperform TEE, MPC, or ZKP in every aspect. Its poor performance makes widespread adoption difficult, as its computation speed lags far behind other approaches. In applications sensitive to real-time performance and cost, TEE, MPC, or ZKP are often more feasible.

Trust models and applicability also differ: TEE and MPC offer distinct trust frameworks and deployment convenience, while ZKP focuses on verifying correctness. As industry perspectives suggest, each privacy tool has strengths and limitations—there is no “one-size-fits-all” optimal solution. For example, ZKP efficiently verifies complex off-chain computations; MPC is more direct for scenarios where multiple parties need to jointly compute over private states; TEE provides mature support in mobile and cloud environments; and FHE suits highly sensitive data processing but currently requires hardware acceleration to be viable.

FHE is not universally superior. The choice of technology should depend on application requirements and performance trade-offs. Future privacy computing will likely involve complementary integration of multiple technologies rather than dominance by a single approach. For instance, Ika focuses on key sharing and signature coordination (users always retain part of the key), with its core value being decentralized asset control without custody. In contrast, ZKP excels at generating mathematical proofs for on-chain verification of states or computation results. They are not simply substitutes or competitors, but rather complementary: ZKP can verify the correctness of cross-chain interactions, reducing trust in bridges, while Ika’s MPC network provides the foundational layer for “asset control,” combinable with ZKP to build more complex systems. Furthermore, Nillion is beginning to fuse multiple privacy technologies to enhance overall capabilities, seamlessly integrating MPC, FHE, TEE, and ZKP in its blind computing architecture to balance security, cost, and performance. Thus, the future of privacy computing will lean toward modular solutions built from the most suitable technological components.

References:

(2)https://blog.sui.io/ika-dwallet-mpc-network-interoperability/

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News