a16z: Why DePIN Matters and How We Can Make It Work

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

a16z: Why DePIN Matters and How We Can Make It Work

By decentralizing these networks, we can not only create a freer society but also achieve a more efficient and prosperous one.

Author: Guy Wuollet

Compiled by: TechFlow

Existing physical infrastructure networks—such as telecommunications, energy, water, and transportation—are typically natural monopolies, where the cost of one company providing a product or service is far lower than what would be required to sustain competition. In most developed countries, these networks are governed by complex regulatory frameworks and government oversight. However, this model offers little incentive for innovation, let alone improvements in customer experience, user interface optimization, service quality, or response speed. Moreover, these networks are often inefficient and poorly maintained. Examples include California wildfires leading to PG&E's bankruptcy, or regulatory policies protecting incumbent telecom providers. In developing countries, the situation is even worse: many such services either don’t exist or are prohibitively expensive and scarce.

We can do better. Decentralized physical infrastructure networks offer an opportunity to move beyond these monopolistic systems and build stronger, more investable, and transparent networks. DePIN (Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks) protocols are user-owned and operated services through which anyone can contribute to running the core infrastructure underlying our daily lives. These protocols have the potential to become powerful democratizing forces, driving greater societal efficiency and openness.

In this article, I’ll explain what DePIN is and why it matters. I will also share a framework for evaluating DePIN protocols and explore key questions to consider when building them—especially around the critical issue of verification.

What Is DePIN?

A decentralized physical infrastructure network (DePIN) refers to any sufficiently decentralized network that uses cryptography and mechanism design to enable clients to request physical services from a set of providers, thereby breaking natural monopolies and unlocking the benefits of competition (which we'll explore in detail below). Clients are typically end users, but may also be applications acting on their behalf. Service providers are usually small businesses, though depending on the network, they might include gig workers or even large traditional companies. Here, “decentralization” refers to the decentralization of power and control—not merely physical distribution or data structure decentralization—as discussed in The Four Horsemen of Centralization.

If well-designed, DePIN protocols can encourage participation from users and small enterprises in physical infrastructure networks, enabling collective governance over time and offering transparent incentives for contributions. Just as the internet is dominated by user-generated content, DePIN opens the door for user-generated services in the physical world. More importantly, just as blockchains are disrupting the “attract-extract” cycle of monopolistic tech firms described here, DePIN protocols can help break utility monopolies in the physical world.

DePIN in Practice: The Energy Grid

Take energy as an example. Even outside crypto, the U.S. electrical grid is already moving toward decentralization. Transmission bottlenecks and long delays in connecting new generation capacity have created demand for decentralized generation. Homes and businesses can deploy solar panels to generate electricity at the grid edge or install batteries to store power. This means they not only buy energy from the grid but can also sell it back.

As edge-based generation and storage become widespread, many devices connected to the grid are no longer owned by utilities. These user-owned devices could greatly benefit the grid by storing and releasing energy at critical moments—so why aren’t they being fully utilized? Existing utilities lack effective access to real-time status data from these devices and cannot purchase temporary control rights over them. Daylight Protocol is addressing this fragmentation in the energy sector. Daylight is building a decentralized network that allows users to sell status data from their grid-connected devices while enabling energy companies to pay for temporary control. In short, Daylight is creating a decentralized virtual power plant.

The result could be a more resilient and efficient energy grid—leveraging user-owned generation capacity, improved data access, and fewer trust assumptions than centralized monopolies. This is precisely the promise of DePIN.

Building DePIN: A Guide

DePIN protocols hold immense potential to improve the core physical infrastructure we interact with every day. But realizing this potential requires overcoming at least three major challenges:

-

Determining whether decentralization is necessary in a given context;

-

Go-to-market strategy;

-

The verification problem—the most challenging of all.

I’ve intentionally omitted domain-specific technical hurdles. Not because they’re unimportant, but because they vary significantly across sectors. Instead, this article focuses on abstract principles for building decentralized networks and offers guidance applicable to all DePIN projects across physical industries.

1. Why Build DePIN?

Two common motivations for building DePIN protocols are: reducing capital expenditure (Capex) for hardware deployment, and aggregating fragmented resource capacity. Additionally, DePIN protocols can create neutral developer platforms atop physical infrastructure, unlocking permissionless innovation—such as open energy data APIs or neutral ride-hailing markets. Through decentralization, DePIN protocols achieve censorship resistance, eliminate platform risk, and foster permissionless innovation—features whose composability and openness fueled the rise of Ethereum and Solana. Traditionally, deploying physical infrastructure has been prohibitively expensive, requiring centralized entities. DePIN distributes both cost and control via decentralized ownership.

1.1 Capital Expenditure (Capex)

Many DePIN protocols reduce the massive—or even prohibitive—capital expenditures typically borne by centralized companies by incentivizing users to purchase hardware and participate in network operations. High Capex is one reason many infrastructure projects are considered natural monopolies; lowering it gives DePIN protocols a structural advantage.

Consider telecommunications. Adoption of new network standards often stalls due to the high upfront costs of hardware deployment. For instance, one analysis estimates that deploying 5G cellular networks in the U.S. alone could require up to $275 billion in private investment.

In contrast, the DePIN network Helium successfully deployed the world’s largest long-range, low-power network (LoRaWAN) without any single entity making large upfront hardware investments. LoRaWAN is ideal for Internet of Things (IoT) use cases. Helium partnered with hardware manufacturers to develop LoRaWAN routers, allowing users to purchase them directly. These users then became owners and operators of the network, providing connectivity to clients who need LoRaWAN and earning rewards in return. Today, Helium is expanding into 5G cellular coverage.

Deploying an IoT network like Helium traditionally involves massive upfront Capex risk—betting that enough customers will eventually adopt the new network. As a DePIN protocol, however, Helium validated supply-side demand in a decentralized way and dramatically reduced its cost structure.

1.2 Resource Capacity

In some cases, vast latent capacity exists within physical resources but remains underutilized due to complexity. Take unused hard drive space: individually too small to interest cloud providers like AWS. Yet when aggregated via DePIN protocols like Filecoin, this fragmented storage becomes a viable cloud service. DePIN leverages blockchain technology to coordinate ordinary users’ resources, enabling broad contributions to large-scale networks.

1.3 Permissionless Innovation

The most transformative capability unlocked by DePIN is permissionless innovation: anyone can build on top of the protocol. This stands in stark contrast to monopolistic infrastructure like local utility grids. Compared to reducing Capex or aggregating capacity, the potential of permissionless innovation is often underestimated.

Permissionless innovation enables physical infrastructure to evolve at software speed. We often hear that digital domains (“bits”) innovate rapidly, while physical domains (“atoms”) lag behind. DePIN provides a crucial path to make “atoms” behave more like “bits.” When anyone with internet access can propose novel ways to organize and coordinate the physical systems powering our world, creative minds will inevitably invent better solutions than those currently available.

1.4 Composability

The reason permissionless innovation accelerates the shift from atoms to bits lies in composability. Composability allows developers to focus on building best-in-class point solutions that can be easily integrated. We’ve seen this power in action with DeFi’s “money legos.” Similarly, DePIN enables “infrastructure legos” to achieve comparable impact.

2. Go-to-Market: Opportunities and Challenges

Building a DePIN protocol is harder than building a blockchain—it must simultaneously solve challenges faced by both decentralized protocols and traditional businesses. Bitcoin and Ethereum launched largely independent of legacy finance and cloud computing, whereas most DePIN protocols are deeply intertwined with existing physical-world problems.

From day one, most DePIN projects must interact with entrenched centralized systems. Think utilities, cable companies, ride-hailing platforms, and ISPs—incumbents often protected by regulation and strong network effects. New entrants struggle to compete. Just as decentralized networks are the natural antidote to internet monopolies, DePIN networks are the natural remedy for physical infrastructure monopolies.

Yet DePIN builders must first identify valuable entry points and gradually expand from there to challenge the entire incumbent system. Choosing the right entry point is critical for long-term success. Builders must also understand how their network will interface with existing alternatives. Most traditional companies resist running full blockchain nodes and find self-custody or on-chain transactions difficult. They often don’t grasp the significance or value of crypto.

One approach is to demonstrate the value of the DePIN protocol—without mentioning it runs on crypto. When incumbents begin to see tangible benefits or integration opportunities, they become more receptive to adopting cryptographic components. More broadly: developers should tailor the protocol’s value proposition to different audiences and craft narratives that resonate emotionally.

Tactically, interfacing with existing networks often requires early intermediation and careful entity structuring—highly dependent on the specific physical domain targeted by the protocol.

Enterprise sales pose another challenge for DePIN. It’s typically a “white-glove,” time-consuming process requiring customization. Customers want a clear point of accountability. But in a DePIN network, no single individual or company represents the whole network or manages enterprise sales workflows.

One solution is to partner with centralized companies as initial distributors who resell the service. For example, a centralized telecom provider could sell services directly to consumers in USD, while the underlying service is delivered via a decentralized telecom network. This abstracts away complex wallet setups and self-custody issues, hiding the “crypto” aspect. This model—where centralized entities distribute DePIN-powered services—is sometimes called a “DePIN mullet,” analogous to the popular “DeFi mullet” pattern in financial services.

3. The Hard Part: Verification

The most difficult aspect of building a DePIN protocol is verification. Verification is essential: it’s the only clear way to ensure customers receive the services they pay for and that providers are fairly compensated for their work.

3.1 Peer-to-Pool vs. Peer-to-Peer

Most DePIN projects adopt a **peer-to-pool** model. In this setup, clients send requests to the network, which assigns a provider to fulfill the request. Crucially, clients pay the network, and the network pays the provider.

An alternative is the peer-to-peer (P2P) model, where clients directly request services from providers. This requires clients to discover a set of providers and select one to work with, paying them directly.

Verification is more critical in peer-to-pool models. In P2P models, although either party might lie, since payment flows directly from client to provider, both can detect fraud independently and simply stop transacting—without needing the network to adjudicate. In peer-to-pool models, however, the network needs a mechanism to resolve disputes between clients and providers. Providers typically agree to serve any client assigned by the network, so preventing or resolving disputes requires some form of decentralized verification.

There are two main reasons DePIN projects choose peer-to-pool designs. First, it makes subsidization via native tokens easier. Second, it improves user experience (UX) and reduces the off-chain infrastructure needed to use the network. A similar distinction exists outside DePIN: compare pool-based DEXs like Uniswap with peer-to-peer DEXs like 0x.

Tokens matter because they help solve the cold start problem when building networks. Whether Web2 or Web3, projects often offer strong value via subsidies to bootstrap network effects. These may take the form of direct economic incentives (e.g., lower costs) or non-scalable value-added services. Tokens often provide economic subsidies while helping build community and giving users a voice in the network’s evolution.

The peer-to-pool model allows clients to pay X while providers receive Y, where X < Y. This gap is typically bridged using the project’s native token, which rewards providers. Because speculators buy the token and assign it a market price higher than its initial (often near-zero) value when usage is low, reward Y can exceed payment X.

The ultimate goal is that as providers improve efficiency, the DePIN project achieves X > Y through network effects, turning the difference into protocol revenue.

In contrast, implementing token-based subsidies in peer-to-peer models is much harder. If clients pay X and providers receive Y, with X < Y, and if clients and providers interact directly, providers could engage in “self-dealing”—pretending to be clients buying services from themselves. This behavior is difficult to prevent in a decentralized DePIN protocol unless some level of centralization is introduced or a peer-to-pool model adopted.

3.2 Self-Dealing

Self-dealing occurs when a user acts as both client and provider, attempting to extract value from the network by transacting with themselves. This is clearly harmful, so most DePIN projects aim to prevent it.

The simplest solution is to avoid subsidies or token incentives altogether—but this makes solving the cold start problem much harder.

Self-dealing is especially dangerous when the cost of self-provisioning is zero—which is often the case. One common mitigation is requiring providers to stake tokens (usually the native token), with client requests allocated based on staking weight.

While staking helps, it doesn’t fully solve the problem. Large providers (those with significant stakes) can still profit from partially self-assigned requests. For example, if a provider’s reward is five times the client’s cost, a provider staking 25% of total tokens gains five tokens for every four spent.

This assumes zero cost for self-provisioning and no gain from requests assigned to others. If self-dealers can extract partial value from other providers’ assigned requests, they may extract even more value under certain cost-to-reward ratios.

3.3 Verification Mechanisms

Having established why verification is critical, let’s examine the different mechanisms DePIN projects can consider.

Consensus

Most blockchains rely on consensus mechanisms (often combined with Sybil-resistance techniques like Proof-of-Work PoW or Proof-of-Stake PoS). Reframing “consensus” as “re-execution” can clarify its function: each node forming consensus typically re-executes every computation processed by the network. (This doesn’t fully apply to modular blockchains separating consensus, execution, and data availability.)

Re-execution is necessary because each node is assumed potentially Byzantine (Byzantine behavior). Nodes must verify each other’s work due to mutual distrust. When a new state change is proposed, every validating node must execute it—resulting in massive redundancy. For example, at the time of writing, Ethereum has over 6,000 nodes.

Re-execution is usually transparent unless the blockchain uses Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs, also known as hardware or secure enclaves) or Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE). See below for details on these technologies.

Proof of Correct Execution (e.g., Validity Rollups, ZEXE)

Instead of requiring every node to re-execute every state change, a single node can execute a given change and generate a proof of correct execution. Verifying this proof is faster than re-executing the computation—a property known as succinctness. The most common forms are SNARKs (Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge) and STARKs (Succinct Transparent Arguments of Knowledge). These are often extended to Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs), proving a statement without revealing any information about it. Thus, SNARKs/STARKs and ZKPs are frequently conflated when used to compress computational proofs.

The best-known blockchains using Proof of Correct Execution are Zero-Knowledge Rollups (ZKRs). A ZKR is a Layer-2 blockchain inheriting security from a base Layer-1 chain. It batches transactions, generates a proof of correct execution, and posts the proof to L1 for verification.

These proofs are primarily used to enhance blockchain scalability and performance, privacy, or both. zkSync, Aztec, Aleo, and Ironfish are notable examples. They're also being applied beyond blockchains—for instance, Filecoin uses ZK-SNARKs in its Proof of Storage. Recently, Proof of Correct Execution has entered machine learning inference (ML inference), training (ML training), and identity verification.

Random Sampling / Statistical Measurement

Another approach to verification in DePIN is randomly sampling providers and measuring their response accuracy to client requests. These “challenge requests” are typically distributed proportionally to a provider’s stakeweight, aiding both verification and self-dealing prevention.

Since many DePIN projects offer high availability rewards (often exceeding per-request rewards), random sampling ensures providers remain truly available. The network occasionally sends challenge requests; if a provider responds correctly and the request hash exceeds a difficulty threshold, they earn a block-like reward. This incentivizes rational providers to respond honestly to all requests, as they cannot distinguish regular from challenge requests.

Versions of random sampling are widely used in DePIN projects focused on network functions, such as Nym, Orchid, and Helium.

Compared to consensus, random sampling scales better, as the number of samples can be far smaller than the volume of state changes.

Trusted Hardware

Trusted hardware isn't just useful for privacy (as noted above)—it can also verify sensor data. A major challenge for DePIN is the oracle problem: how to bring real-world data onto blockchains in a trust-minimized way. Trusted hardware allows networks to adjudicate disputes between clients and providers based on physical sensor outputs.

Though trusted hardware often has vulnerabilities, it may serve as a pragmatic short-to-medium-term solution or an additional defense layer. Common Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) include Intel SGX, Intel TDX, and ARM TrustZone. Projects like Oasis, Secret Network, and Phala use TEEs, and SAUVE plans to as well.

Whitelisting and Auditing

The most practical and technically simple verification method is whitelisting specific physical devices to participate in the DePIN protocol and manually auditing logs and telemetry data to ensure providers serve clients correctly.

In practice, this often involves custom hardware with embedded signing keys, requiring all network participants to purchase devices from verified manufacturers. Manufacturers whitelist a set of embedded keys, and only data signed with whitelisted keys is accepted. This assumes extracting embedded keys is extremely difficult and that manufacturers accurately report which keys are embedded in which devices. To address risks, manual audits are typically conducted.

To further ensure correctness, DePIN protocols often elect a human “auditor” via governance to detect malicious behavior and report findings. Auditors, being human, can spot sophisticated attacks that automated protocols might miss—attacks that, once identified, may seem obvious. Auditors are usually empowered to propose penalties (like slashing stakes) to governance or trigger slashing directly. This assumes governance acts in the protocol’s best interest and acknowledges the human incentive challenges inherent in social consensus.

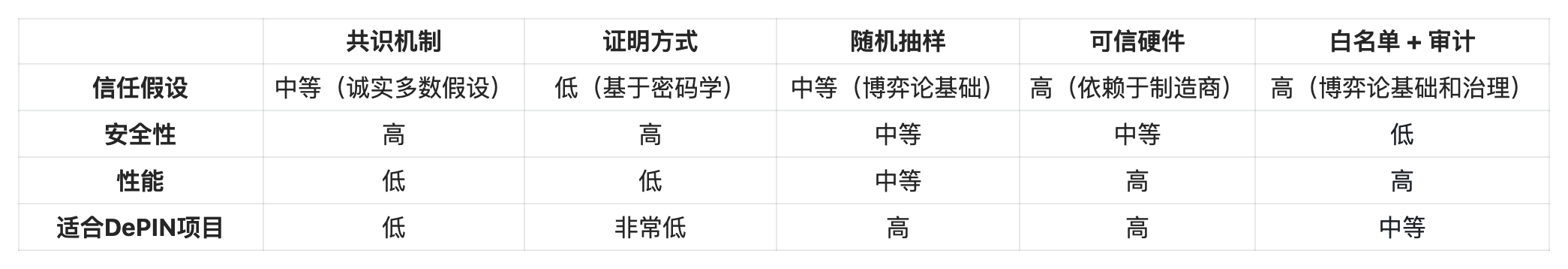

Which Approach Is Best?

Faced with multiple verification options, new DePIN protocols often struggle to choose.

Consensus and Proof of Correct Execution are generally infeasible for DePIN. These mechanisms offer strong guarantees only for computational (digital) state changes, not physical services. Using them in DePIN requires introducing oracles, which come with their own (often weaker) trust assumptions.

Random sampling is well-suited to DePIN: it’s efficient, game-theoretically sound, and works well for physical services. Trusted hardware and whitelisting are often the easiest starting points—though they are the most centralized and less likely to succeed long-term.

Why DePIN Matters

Cryptocurrency gained popularity from the desire to free money from state control. But arguably more important services—like basic internet access, electricity, and clean water—are concentrated in the hands of a few. By decentralizing these networks, we can create not only a freer society but also a more efficient and prosperous one.

A decentralized future means many—not just a privileged few—can contribute better solutions. This stems from the belief that human potential is universally distributed. If you’re excited about decentralized finance or decentralized developer platforms, consider extending that vision to other essential networked services we use every day.

About the Author

Guy Wuollet is a Partner at a16z Crypto, focusing on full-stack investments across the crypto landscape. Prior to a16z, Guy collaborated with Protocol Labs on independent research aimed at building decentralized network protocols and upgrading internet infrastructure. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Computer Science from Stanford University and was a varsity rower on the university crew team.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News