In-Depth Investigation of Rug Pull Cases: Exposing the Chaos in Ethereum's Token Ecosystem

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

In-Depth Investigation of Rug Pull Cases: Exposing the Chaos in Ethereum's Token Ecosystem

Stay vigilant against the ever-emerging scams and take timely preventive measures to safeguard your assets.

Author: CertiK

Introduction

In the Web3 world, new tokens emerge constantly. Have you ever wondered how many new tokens are issued each day? And are these newly launched tokens safe?

These questions are not unfounded. Over recent months, the CertiK security team has detected a large number of Rug Pull transactions. Notably, all tokens involved in these cases were freshly deployed on-chain.

CertiK conducted an in-depth investigation into these Rug Pull incidents and discovered organized criminal groups behind them, identifying patterned characteristics of such scams. By analyzing their operational methods, CertiK uncovered a potential promotional channel used by these fraudsters: Telegram groups. These groups leverage "New Token Tracer" features within tools like Banana Gun and Unibot to lure users into purchasing scam tokens, enabling the perpetrators to profit via Rug Pulls.

CertiK analyzed token announcement data from these Telegram groups between November 2023 and early August 2024, finding that they promoted 93,930 new tokens during this period—of which 46,526 (49.53%) were linked to Rug Pulls. According to statistics, the total investment cost for these scam operations amounted to 149,813.72 ETH, generating illicit profits of 282,699.96 ETH at a return rate of 188.7%, equivalent to approximately $800 million USD.

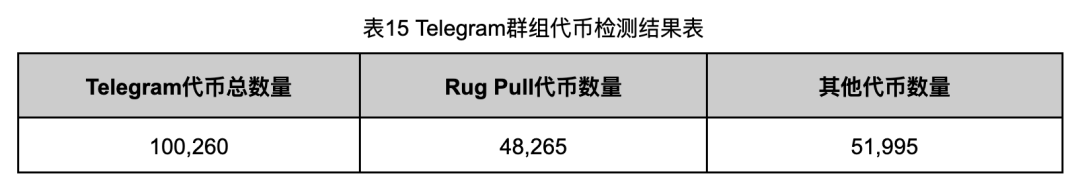

To evaluate the proportion of Telegram-promoted tokens among all new tokens on the Ethereum mainnet, CertiK collected issuance data for the same timeframe. The data shows that 100,260 new tokens were launched on Ethereum during this period, with 89.99% of them being advertised through Telegram groups. On average, about 370 new tokens are created daily—far exceeding reasonable expectations. After extensive investigation, we uncovered a disturbing truth: at least 48,265 of these tokens (48.14%) were fraudulent. In other words, nearly one out of every two newly issued tokens on the Ethereum mainnet is part of a scam.

Furthermore, CertiK has identified even more Rug Pull cases across other blockchain networks, indicating that the security situation within the broader Web3 token launch ecosystem is far worse than anticipated. Therefore, CertiK has published this research report to help all Web3 participants enhance their awareness, remain vigilant against ever-evolving scams, and take timely preventive measures to protect their assets.

ERC-20 Tokens

Before diving into the report, let's review some fundamental concepts.

ERC-20 is one of the most common token standards on blockchains. It defines a set of rules enabling interoperability between different smart contracts and decentralized applications (dApps). The ERC-20 standard specifies core functionalities such as transferring tokens, checking balances, and authorizing third parties to manage tokens. Thanks to this standardized protocol, developers can issue and manage tokens more easily, streamlining both creation and usage processes. Indeed, any individual or organization can issue their own token based on the ERC-20 standard and raise initial funding through token presales. Due to its widespread adoption, ERC-20 has become foundational for many ICOs and DeFi projects.

Familiar tokens like USDT, PEPE, and DOGE are all ERC-20 tokens, purchasable via decentralized exchanges (DEXs). However, malicious actors may also deploy ERC-20 tokens embedded with backdoors, list them on DEXs, and trick users into buying them.

Typical Rug Pull Scam Case

Here, we examine a real Rug Pull case to understand how malicious token scams operate. First, it’s important to clarify that “Rug Pull” refers to a type of fraud where project founders abruptly withdraw funds or abandon a DeFi project, causing massive losses to investors. A “Rug Pull token” is specifically created to carry out such fraudulent activities.

The Rug Pull tokens discussed in this article are sometimes referred to as “Honey Pot tokens” or “Exit Scam tokens,” but we will uniformly refer to them as Rug Pull tokens throughout the following sections.

· Case Study

An attacker (Rug Pull gang) uses a Deployer address (0x4bAF) to deploy the TOMMI token, then creates a liquidity pool using 1.5 ETH and 100,000,000 TOMMI tokens. They use other addresses to actively buy TOMMI tokens to fabricate trading volume, attracting users and sniping bots to purchase the token. Once enough sniping bots have fallen for the trap, the attacker executes the Rug Pull using a dedicated Rug Puller address (0x43a9), dumping 38,739,354 TOMMI tokens into the liquidity pool and withdrawing approximately 3.95 ETH. The Rug Puller obtains these tokens through a malicious approve authorization built into the TOMMI contract—the contract grants the Rug Puller pre-approved transfer rights when initially deployed, allowing direct withdrawal from the liquidity pool.

· Related Addresses

-

Deployer: 0x4bAFd8c32D9a8585af0bb6872482a76150F528b7

-

TOMMI Token: 0xe52bDD1fc98cD6c0cd544c0187129c20D4545C7F

-

Rug Puller: 0x43A905f4BF396269e5C559a01C691dF5CbD25a2b

-

One of the fake user addresses used by Rug Puller: 0x4027F4daBFBB616A8dCb19bb225B3cF17879c9A8

-

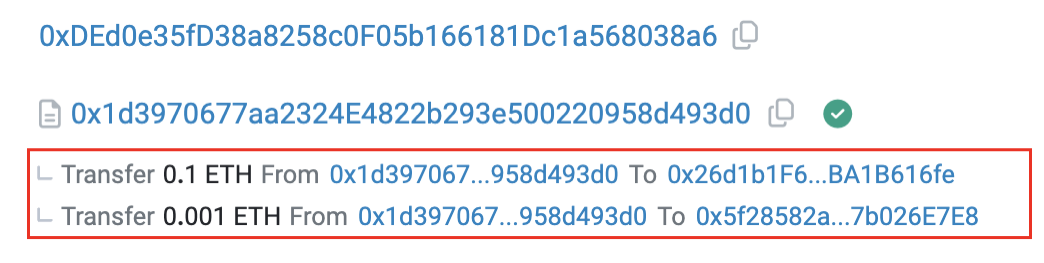

Funds relay address: 0x1d3970677aa2324E4822b293e500220958d493d0

-

Funds retention address: 0x28367D2656434b928a6799E0B091045e2ee84722

· Relevant Transactions

-

Deployer receives seed capital from centralized exchange: 0x428262fb31b1378ea872a59528d3277a292efe7528d9ffa2bd926f8bd4129457

-

Deploy TOMMI token: 0xf0389c0fa44f74bca24bc9d53710b21f1c4c8c5fba5b2ebf5a8adfa9b2d851f8

-

Create liquidity pool: 0x59bb8b69ca3fe2b3bb52825c7a96bf5f92c4dc2a8b9af3a2f1dddda0a79ee78c

-

Funds relay address sends money to one fake user: 0x972942e97e4952382d4604227ce7b849b9360ba5213f2de6edabb35ebbd20eff

-

Fake user purchases token (one example): 0x814247c4f4362dc15e75c0167efaec8e3a5001ddbda6bc4ace6bd7c451a0b231

-

Rug Pull execution: 0xfc2a8e4f192397471ae0eae826dac580d03bcdfcb929c7423e174d1919e1ba9c

-

Rug Pull proceeds sent to relay address: 0xf1e789f32b19089ccf3d0b9f7f4779eb00e724bb779d691f19a4a19d6fd15523

-

Relay address forwards funds to retention address: 0xb78cba313021ab060bd1c8b024198a2e5e1abc458ef9070c0d11688506b7e8d7

· Rug Pull Process

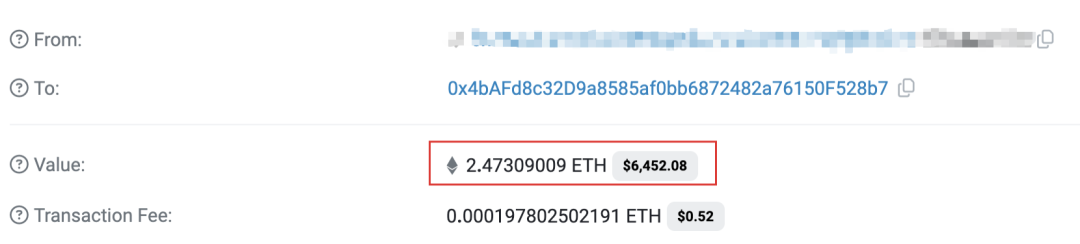

1. Prepare attack capital.

The attacker deposits 2.47309009 ETH from a centralized exchange to the Token Deployer address (0x4bAF) as startup capital for the Rug Pull.

Figure 1: Transaction details showing Deployer receiving funds from exchange

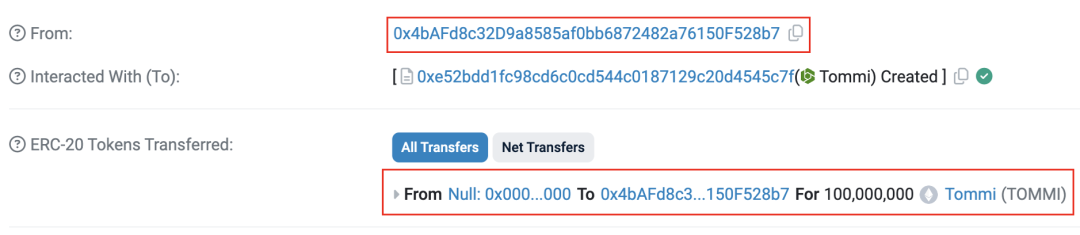

2. Deploy a backdoored Rug Pull token.

The Deployer creates the TOMMI token, pre-mining 100,000,000 tokens and allocating them to itself.

Figure 2: Transaction details showing TOMMI token deployment

3. Create initial liquidity pool.

The Deployer establishes a liquidity pool with 1.5 ETH and all pre-mined tokens, receiving approximately 0.387 LP tokens.

Figure 3: Capital flow diagram for Deployer creating the liquidity pool

4. Burn all pre-mined token supply.

The Token Deployer sends all LP tokens to the zero address for destruction. Since the TOMMI contract lacks a mint function, the Deployer theoretically loses the ability to perform a Rug Pull (a key tactic to deceive sniping bots—some bots check whether deployers retain minting or ownership control). The Deployer also sets the contract owner to the zero address to further bypass bot-based anti-scam checks.

Figure 4: Transaction details showing LP token burn

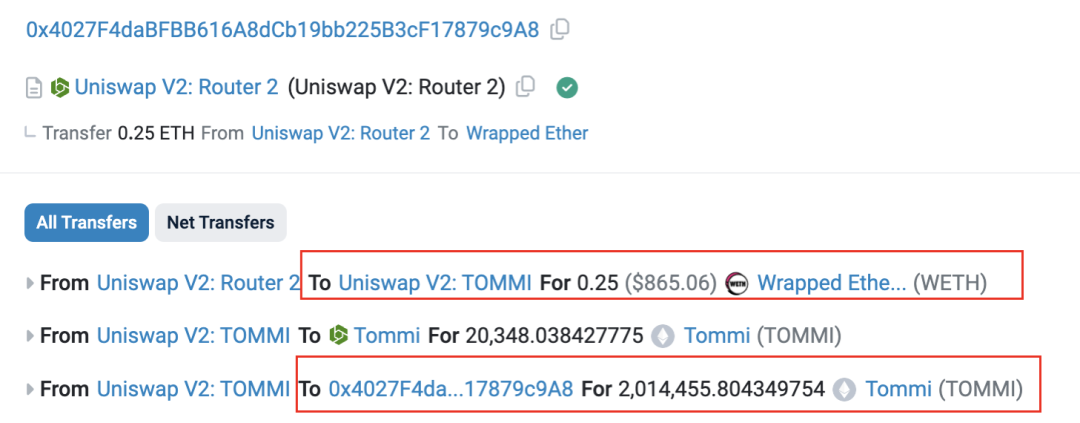

5. Fabricate trading volume.

The attackers use multiple addresses to actively buy TOMMI tokens from the liquidity pool, inflating trading volume and luring sniping bots. Evidence that these are attacker-controlled addresses lies in their shared funding origin—the historical fund-relay address used by the Rug Pull gang.

Figure 5: Transaction and fund flow details of attacker addresses purchasing TOMMI

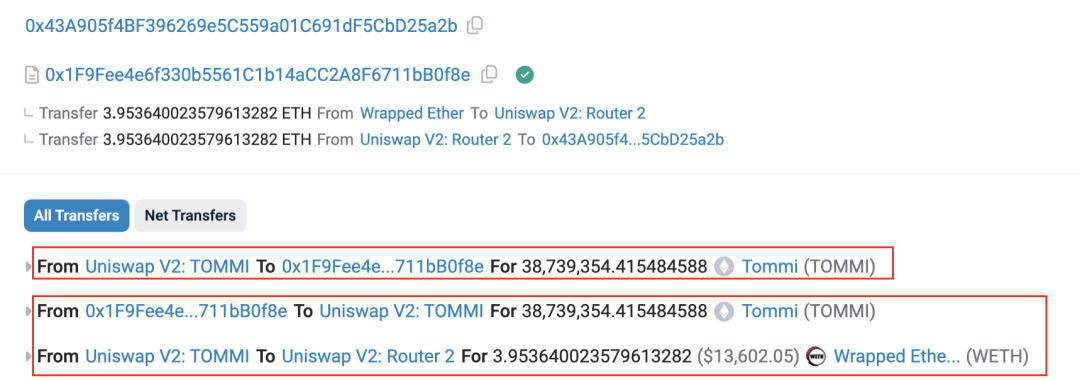

6. The attacker executes the Rug Pull via the Rug Puller address (0x43A9), exploiting the backdoor to directly withdraw 38,739,354 TOMMI tokens from the liquidity pool, then dumps them to extract ~3.95 ETH.

Figure 6: Rug Pull transaction and fund flow

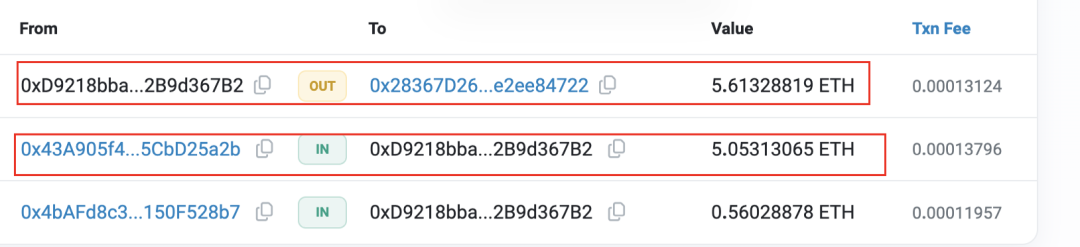

7. The attacker transfers the stolen funds to the relay address 0xD921.

Figure 7: Transaction showing Rug Puller sending proceeds to relay address

8. Relay address 0xD921 forwards funds to retention address 0x2836. This marks the final stage: after the Rug Pull, funds are consolidated into long-term storage addresses. Retention addresses serve as aggregation points observed across numerous Rug Pull cases. Most of the received funds are split and reused for future scams, while smaller portions are cashed out via centralized exchanges. We've identified several such retention addresses, with 0x2836 being one.

Figure 8: Fund transfer from relay address

· Rug Pull Code Backdoor

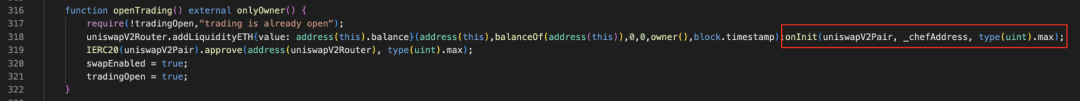

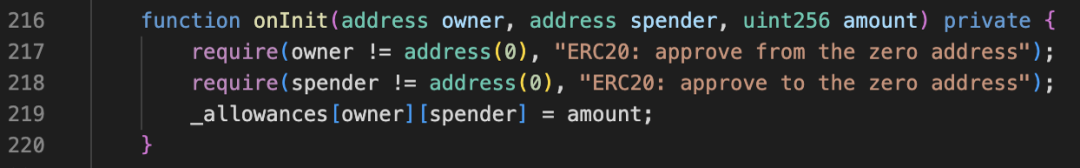

Although the attacker appears to eliminate Rug Pull capability by burning LP tokens, the TOMMI contract contains a malicious approve backdoor inside the openTrading function. During liquidity pool creation, this backdoor grants the Rug Puller address unlimited approval to transfer tokens directly from the pool.

Figure 9: openTrading function in TOMMI token contract

Figure 10: onInit function in TOMMI token contract

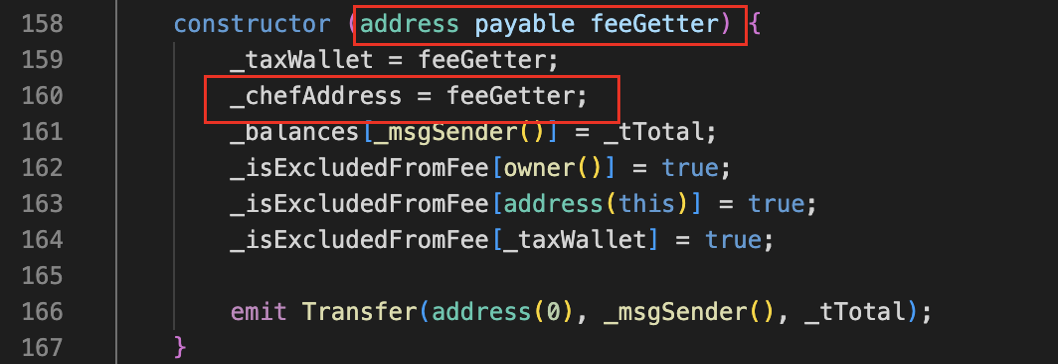

The openTrading function (Figure 9) primarily creates a new liquidity pool, but secretly calls the backdoor function onInit (Figure 10), granting uniswapV2Pair (the pool address) unlimited approval to transfer tokens to _chefAddress (the Rug Puller address). _chefAddress is predefined during contract deployment (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: Constructor in TOMMI token contract

· Patterned Modus Operandi

From analyzing the TOMMI case, we identify four recurring patterns:

1. Deployer acquires funds via centralized exchanges: Attackers first obtain capital through CEX withdrawals to the Deployer address.

2. Deployer creates liquidity pool and burns LP tokens: After deploying the malicious token, the attacker immediately creates a liquidity pool and burns LP tokens to boost credibility and attract investors.

3. Rug Puller dumps large amounts of tokens for ETH: The Rug Puller address uses excessive tokens (often exceeding total supply) to drain ETH from the pool. In other cases, attackers remove liquidity entirely.

4. Rug Puller transfers stolen ETH to retention addresses: Proceeds are moved to long-term storage, sometimes via intermediate relay addresses.

These patterns are consistently observed across captured cases, indicating highly systematic behavior. Furthermore, funds often converge into specific retention addresses, suggesting seemingly isolated incidents may be orchestrated by the same or interconnected criminal groups.

Based on these traits, we extracted a behavioral model to scan monitored cases and build potential perpetrator profiles.

Rug Pull Criminal Groups

· Identifying Fund Retention Addresses

As previously noted, Rug Pull schemes typically consolidate illicit gains into fund retention addresses. Leveraging this pattern, we selected several highly active retention addresses with clearly identifiable modus operandi for deeper analysis.

We focused on seven such addresses, collectively linked to 1,124 Rug Pull cases successfully detected by our on-chain attack monitoring system (CertiK Alert). After executing scams, gangs funnel proceeds into these addresses. The retained funds are later fragmented and recycled for launching new scams—including deploying fresh tokens and manipulating liquidity pools. A small portion is cashed out through centralized exchanges or swap platforms.

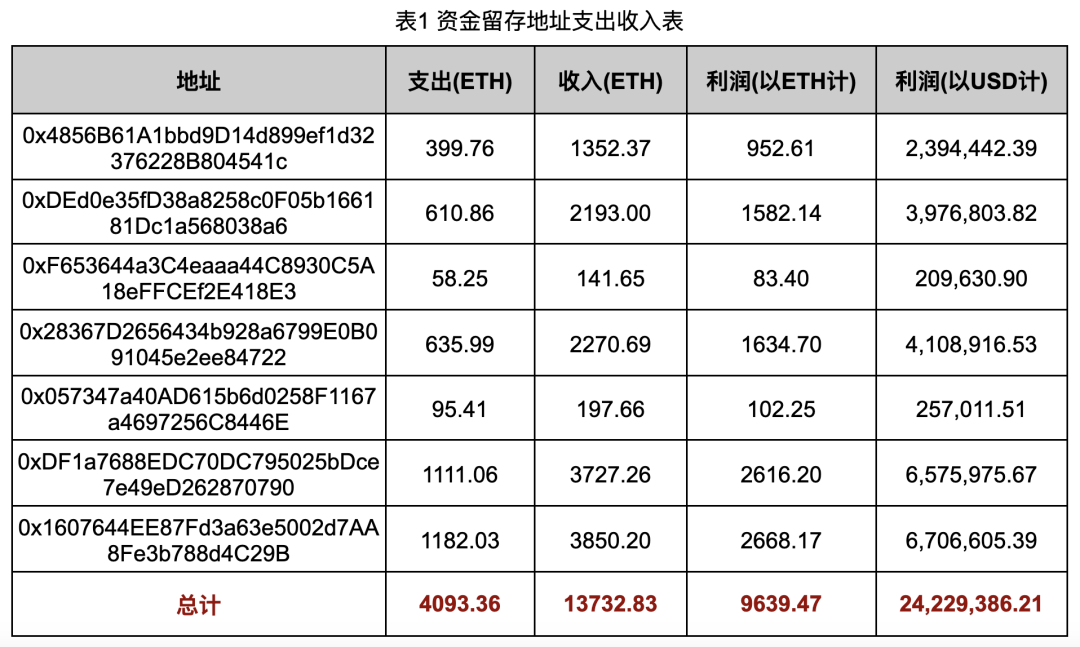

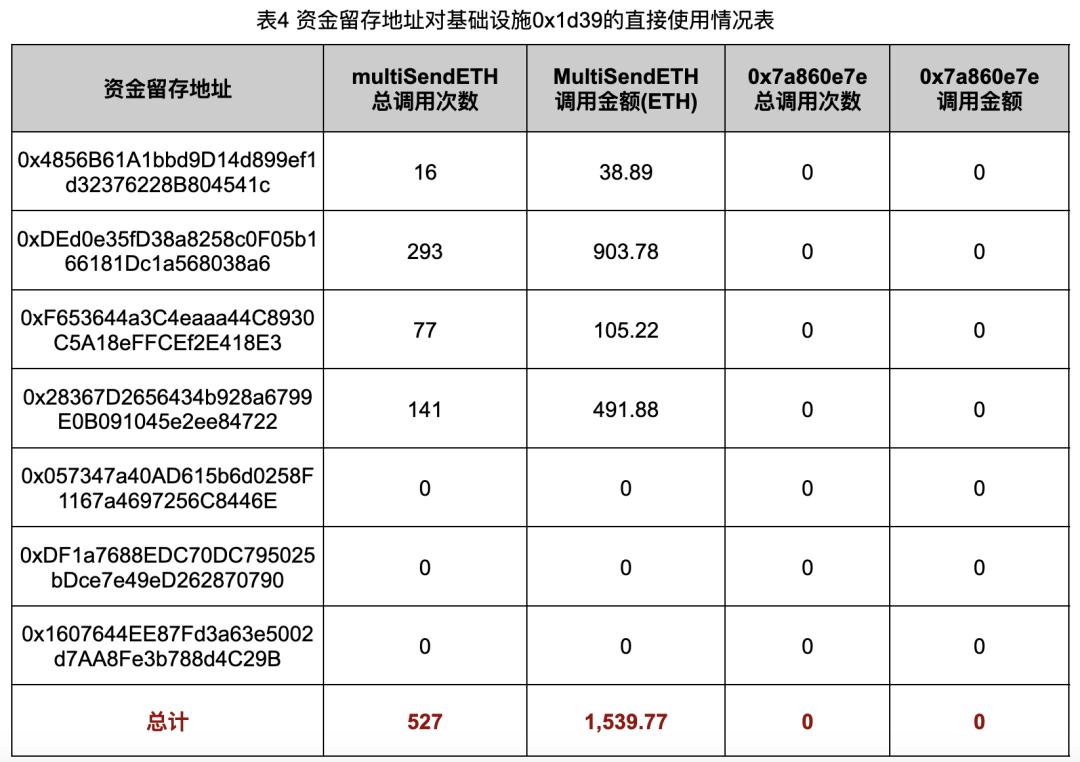

Fund data for these retention addresses is summarized in Table 1:

By aggregating costs and revenues across all associated scams, we derived the figures shown in Table 1.

In a typical Rug Pull operation, the gang uses one address as the token Deployer, obtaining seed capital via CEX withdrawals to deploy the malicious token and establish a liquidity pool. Once sufficient victims or sniping bots have purchased the token using ETH, another address (the Rug Puller) executes the exit, transferring proceeds to a retention address.

We define the cost as either the ETH obtained by the Deployer from the exchange or the ETH contributed to the liquidity pool (depending on Deployer behavior). Revenue is defined as the ETH transferred by the Rug Puller to the retention (or relay) address post-Rug Pull. USD profit was calculated using an ETH price of $2,513.56 (as of August 31, 2024).

Note: Attackers often self-purchase their scam tokens to simulate organic trading activity and lure bots. This additional cost was excluded from calculations, meaning actual profits are likely lower than reported.

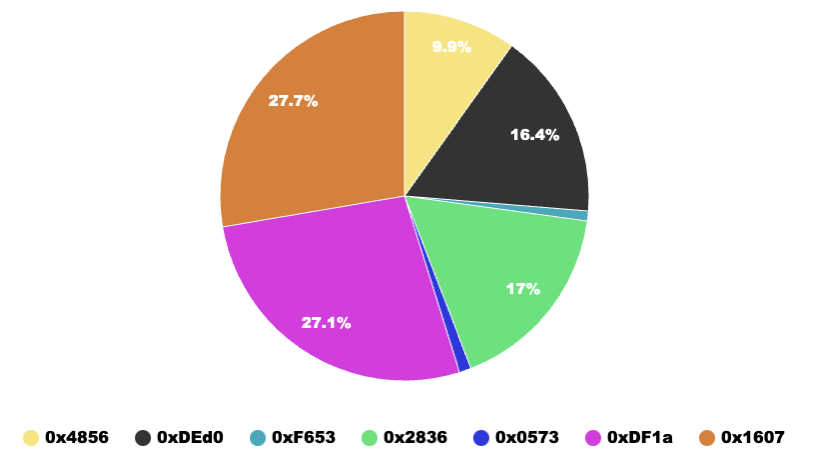

Figure 12: Pie chart showing profit distribution among retention addresses

Using Table 1 data, we generated the profit share pie chart (Figure 12). The top three contributors are 0x1607, 0xDF1a, and 0x2836. Address 0x1607 earned the highest profit (~2,668.17 ETH), accounting for 27.7% of total profits.

Despite funds flowing into different retention addresses, strong similarities in scam mechanics (e.g., backdoor implementation, cash-out paths) suggest they may belong to the same overarching group.

So, do these retention addresses share any direct connections?

· Linking Retention Addresses

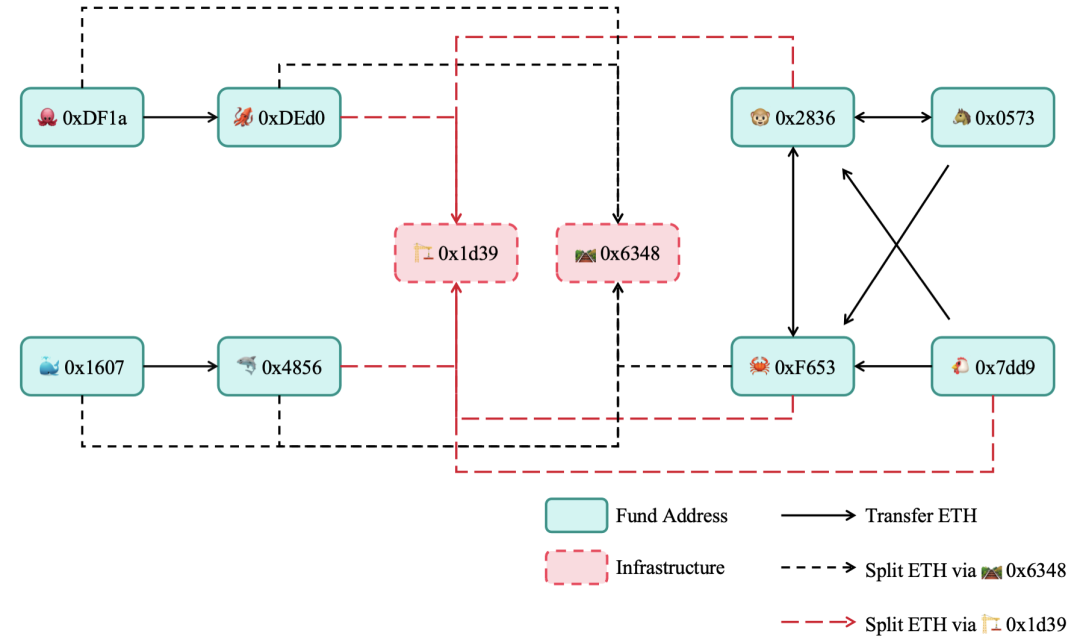

Figure 13: Fund flow diagram among retention addresses

A key indicator of interconnection is direct fund transfers between addresses. To verify relationships, we crawled and analyzed historical transaction records.

In most prior cases, each Rug Pull’s proceeds go to only one retention address, making it difficult to link addresses via revenue trails. Instead, we examined direct fund flows between retention addresses, revealing the structure shown in Figure 13.

Note: Addresses 0x1d39 and 0x6348 in Figure 13 are shared infrastructure contracts used by all retention addresses. These contracts split funds and distribute them to various addresses, which then generate fake trading volume for scam tokens.

Based on direct ETH transfers, we cluster the seven retention addresses into three groups:

1. 0xDF1a and 0xDEd0;

2. 0x1607 and 0x4856;

3. 0x2836, 0x0573, 0xF653, and 0x7dd9.

Addresses within each group exhibit direct transfers, but no cross-group transactions exist. Thus, they could represent three separate gangs. However, all three groups rely on the same two infrastructure contracts for fund splitting and subsequent attacks, effectively linking them into a unified network. Could this imply a single coordinated operation behind all these addresses?

We leave this question open for readers to ponder.

· Shared Infrastructure Analysis

The two primary shared infrastructure addresses are:

0x1d3970677aa2324E4822b293e500220958d493d0 and 0x634847D6b650B9f442b3B582971f859E6e65eB53.

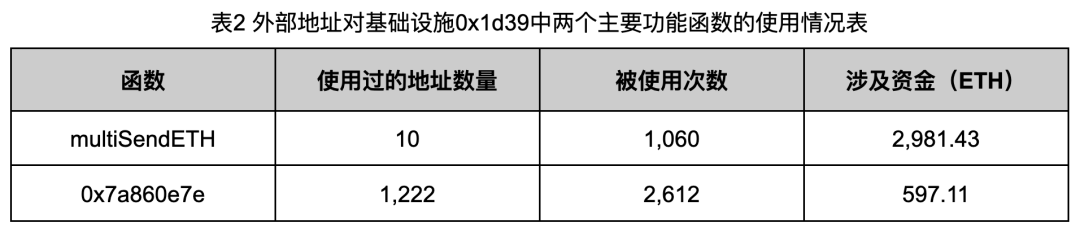

Infrastructure address 0x1d39 includes two main functions: "multiSendETH" and "0x7a860e7e". The "multiSendETH" function enables bulk fund distribution—retention addresses use it to split capital across multiple accounts to simulate trading activity, as seen in Figure 14.

This technique enhances perceived token activity, making scams more convincing and increasing victim acquisition. It significantly raises the complexity and deception level of these frauds.

Figure 14: Transaction details showing fund splitting via 0x1d39

The "0x7a860e7e" function allows direct purchase of scam tokens. After receiving split funds, fake user addresses either interact directly with Uniswap Router or call this function via 0x1d39 to buy tokens and inflate volume.

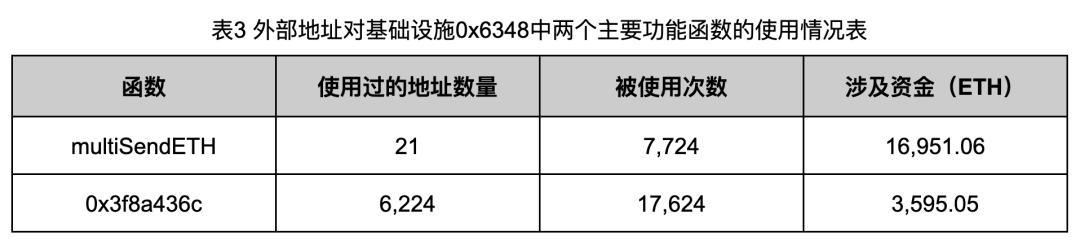

Address 0x6348 offers similar functionality, differing only in function name ("0x3f8a436c" instead of "0x7a860e7e"), so we won’t elaborate further.

To better understand usage patterns, we analyzed transaction histories of 0x1d39 and 0x6348, tabulating external address usage frequency of both functions (Tables 2 and 3).

Data from Tables 2 and 3 reveals clear patterns: attackers use few retention or relay addresses to distribute funds but employ thousands of secondary addresses to generate fake volume. For instance, up to 6,224 distinct addresses used 0x6348 to simulate trades—a scale that greatly complicates distinguishing attackers from victims.

It should be noted that volume manipulation isn't limited to these infrastructures; some attackers directly trade via exchanges.

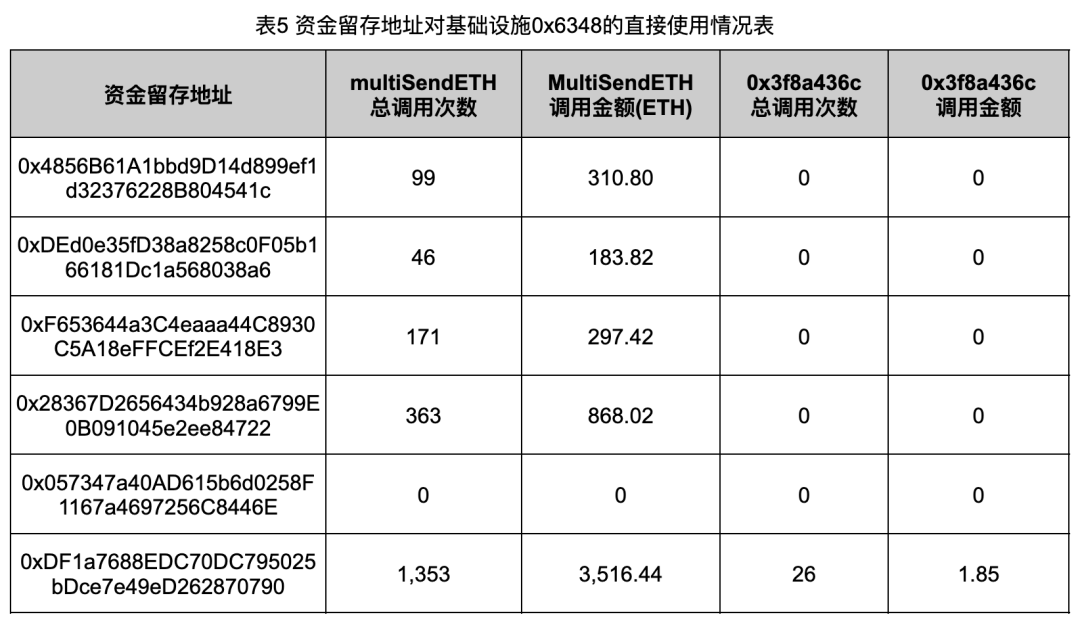

We also tracked usage of both infrastructure functions by the seven retention addresses, including ETH volumes involved (Tables 4 and 5).

Tables 4 and 5 show that infrastructures were used 3,616 times to split a total of 9,369.98 ETH. Except for 0xDF1a, all retention addresses exclusively used infrastructures for fund splitting, delegating token purchases to recipient addresses—indicating clear division of labor.

Address 0x0573 did not use infrastructure for fund splitting; its volume-manipulation funds came from elsewhere, suggesting stylistic differences among groups.

Through this analysis, we gain a comprehensive view of interconnections among retention addresses and their shared tools. These gangs operate with surprising professionalism and organization, pointing to coordinated criminal enterprises conducting systematic fraud.

· Tracing Funding Sources

Rug Pull gangs typically use new EOA addresses as Deployers, sourcing seed capital from CEXs or swap platforms. We analyzed funding sources for Deployers linked to prior retention addresses to uncover detailed patterns.

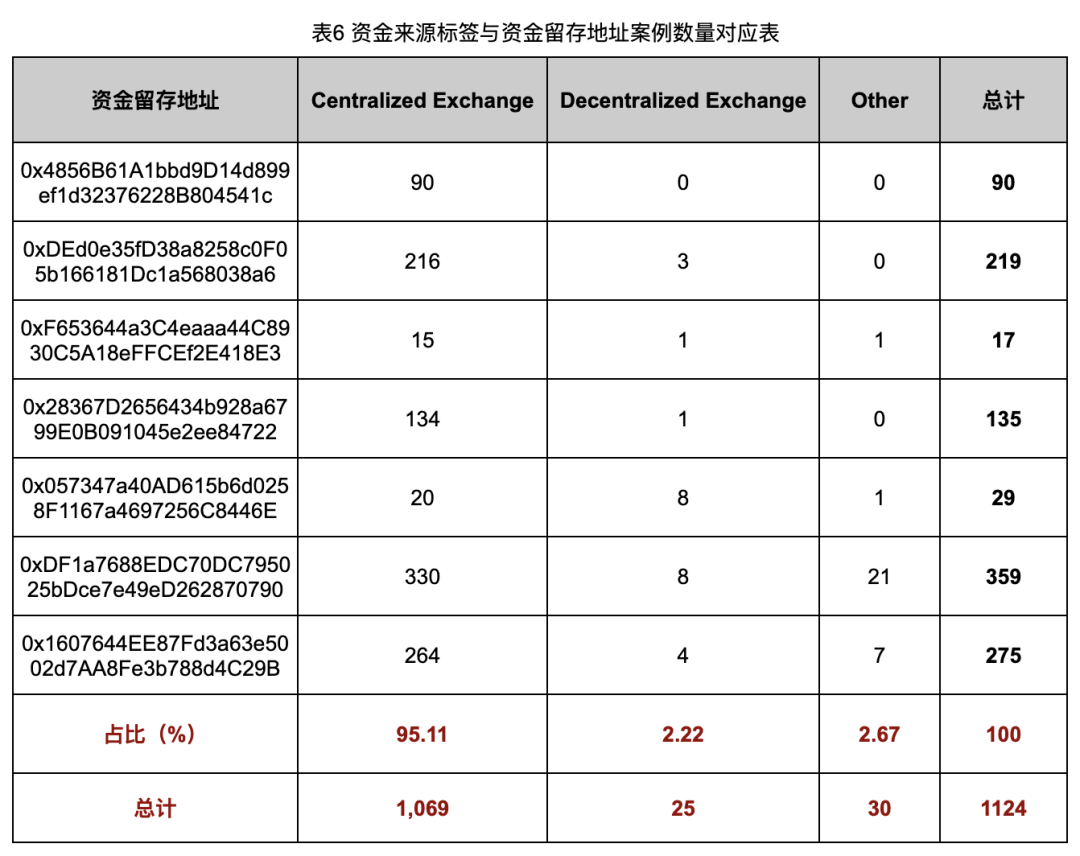

Table 6 shows label distribution of funding sources for Deployers across retention addresses.

Data shows most Deployer funds originate from centralized exchanges (CEXs). Among the 1,124 analyzed Rug Pull cases, 1,069 (95.11%) received funds from CEX hot wallets. This implies that in most cases, KYC data and withdrawal logs from exchanges could provide crucial investigative leads.

Further analysis revealed that gangs often source funds from multiple exchanges, distributing usage evenly—likely to increase financial independence across scams and complicate traceability.

Overall, our findings depict a well-trained, organized, and deliberate criminal network—highly professional and operating systematically.

Facing such sophisticated adversaries, we naturally question their promotion strategy: How do they get users to discover and buy these scam tokens? To answer this, we turned to victim addresses, seeking clues on how users are lured into these traps.

· Identifying Victim Addresses

Using fund linkage analysis, we compiled a blacklist of known attacker addresses and filtered victim addresses from liquidity pool transaction logs of Rug Pull tokens.

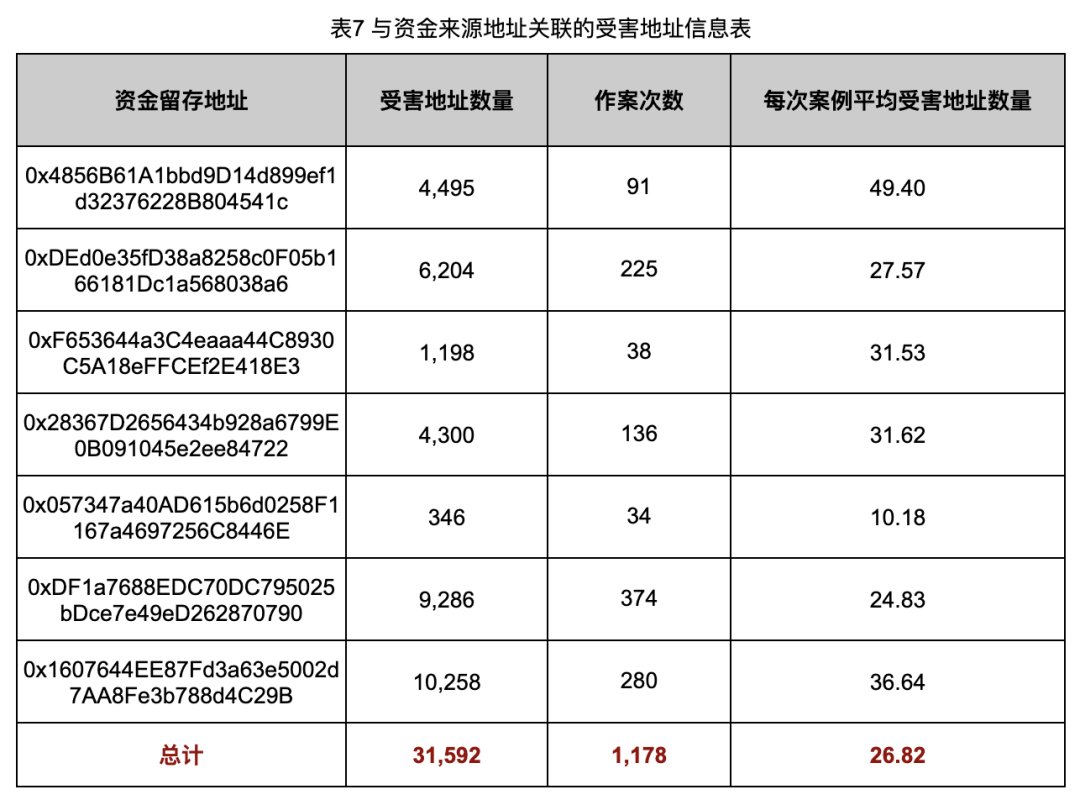

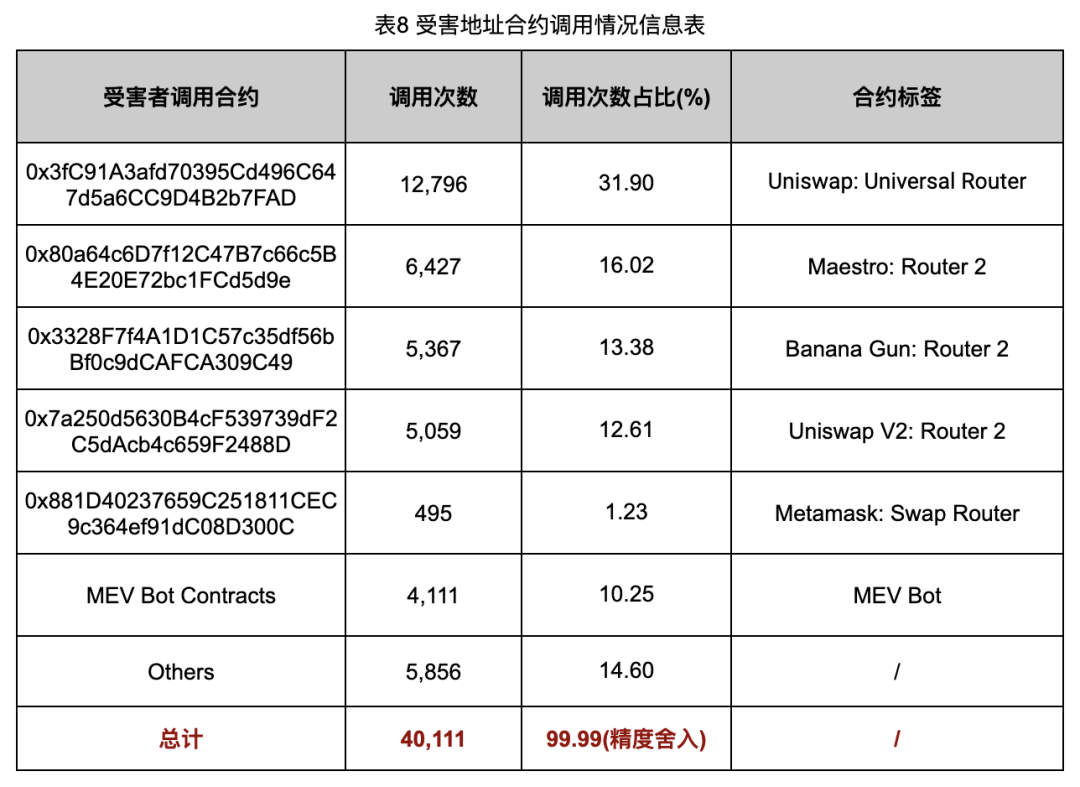

Analysis yielded victim data linked to retention addresses (Table 7) and contract interaction patterns (Table 8).

Table 7 shows an average of 26.82 victims per case—higher than expected, indicating broader harm than initially assumed.

Table 8 reveals that beyond standard platforms like Uniswap and MetaMask Swap, 30.40% of scam token purchases occurred via popular sniper bots such as Maestro and Banana Gun.

This suggests sniper bots are significant distribution channels. They enable rapid attraction of participants, especially those focused on new token launches. Hence, we shifted focus to these bots to understand their role in Rug Pull promotions.

Promotion Channels for Rug Pull Tokens

We surveyed the current Web3 launch ecosystem, studied sniper bot mechanics, and applied social engineering insights, ultimately identifying two likely advertising channels for Rug Pull gangs: Twitter and Telegram groups.

Importantly, these Twitter accounts and Telegram groups were not created by scammers themselves. Rather, they are legitimate components of the launch ecosystem—maintained by sniper bot teams or professional launch groups—to notify users of newly listed tokens. Unfortunately, they’ve become natural conduits for fraudsters to promote malicious tokens.

· Twitter Ads

Figure 15: Twitter ad for TOMMI token

Figure 15 displays a Twitter advertisement for the earlier-mentioned TOMMI token. The scammer leveraged Dexed.com’s new token alert service to expose their scam token and attract victims. Our investigation found that many Rug Pull tokens have corresponding ads on Twitter, posted by various third-party accounts.

· Telegram Group Ads

Figure 16: Banana Gun new token announcement group

Figure 16 shows a Telegram group maintained by the Banana Gun sniper bot team, dedicated to announcing newly launched tokens. The group shares basic token info and provides quick purchase buttons. Once users configure their Banana Gun Sniper Bot settings, clicking the “Snipe” button (highlighted in red) instantly buys the token.

Manual spot-checks of promoted tokens revealed a high proportion were Rug Pull scams. This reinforces our hypothesis that Telegram groups are major advertising vectors for fraudsters.

The critical question now is: What percentage of third-party-promoted tokens are actually scams? And what is the true scale of these criminal operations? To answer this, we decided to systematically scan and analyze token data from Telegram groups, aiming to quantify risk levels and assess the impact of these fraudulent activities.

Ethereum Token Ecosystem Analysis

· Analyzing Tokens Promoted in Telegram Groups

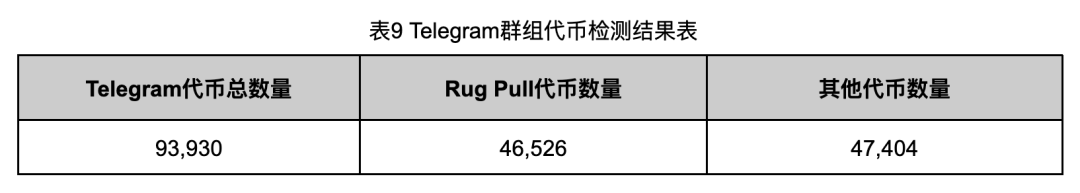

To determine the Rug Pull ratio among tokens promoted in Telegram groups, we used Telegram APIs to scrape new Ethereum token announcements from Banana Gun, Unibot, and other third-party token alert groups between October 2023 and August 2024. During this period, these groups promoted 93,930 tokens.

Based on our Rug Pull analysis, attackers typically create a Uniswap V2 liquidity pool with ETH and execute exits within 24 hours after attracting buyers.

We established the following detection rules to scan these 93,930 tokens and estimate the Rug Pull proportion:

1. No transfer activity in the last 24 hours: Post-exit, Rug Pull tokens usually go dormant;

2. Presence of a Uniswap V2 ETH liquidity pool: Scammers create ETH-based pools;

3. Total Transfer events ≤ 1,000 since creation: Scam tokens generally have low transaction counts;

4. Last 5 transactions include large liquidity removals or dumps: Final actions involve draining the pool.

Applying these rules yielded results shown in Table 10.

As shown in Table 9, among the 93,930 tokens promoted in Telegram groups, 46,526 (49.53%) were flagged as Rug Pulls—nearly half.

Some legitimate projects may legitimately withdraw liquidity upon failure, which shouldn’t be classified as Rug Pull fraud. While Rule 3 filters most such cases, false positives may still occur.

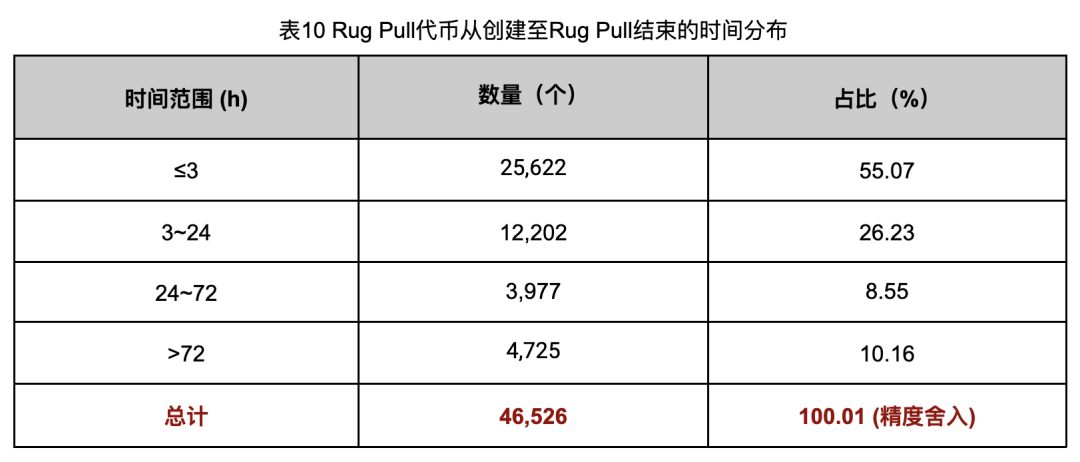

To assess potential false positive impact, we analyzed active durations of the 46,526 flagged tokens (Table 10). Duration helps distinguish genuine Rug Pulls from failed project wind-downs, enabling more accurate assessment.

Duration analysis showed 41,801 (89.84%) had active periods under 72 hours. Given that 72 hours is insufficient to judge project viability, we conclude these short-lived tokens reflect intentional fraud rather than honest exits.

Even assuming all remaining 4,725 tokens (active >72h) are false positives, our analysis remains robust due to the overwhelming majority (89.84%) fitting the fraud profile. In reality, the 72-hour threshold is conservative—sampling shows many >72h tokens still qualify as Rug Pulls.

Notably, 25,622 tokens (55.07%) were active for less than 3 hours, indicating extremely efficient, high-turnover operations with a “quick-in, quick-out” strategy.

We also assessed cash-out methods and contract interaction patterns to understand attacker preferences.

Cash-out method analysis tallied how many cases used each approach:

1. Dumping: Using pre-mined or backdoor-obtained tokens to drain ETH from the pool.

2. Removing liquidity: Withdrawing original deposited funds.

Contract interaction analysis examined target contracts used during Rug Pull execution:

1. DEX Router contracts: Direct pool manipulation.

2. Custom attack contracts: For complex fraud logic.

These assessments deepen our understanding of attacker tactics for improved detection and prevention.

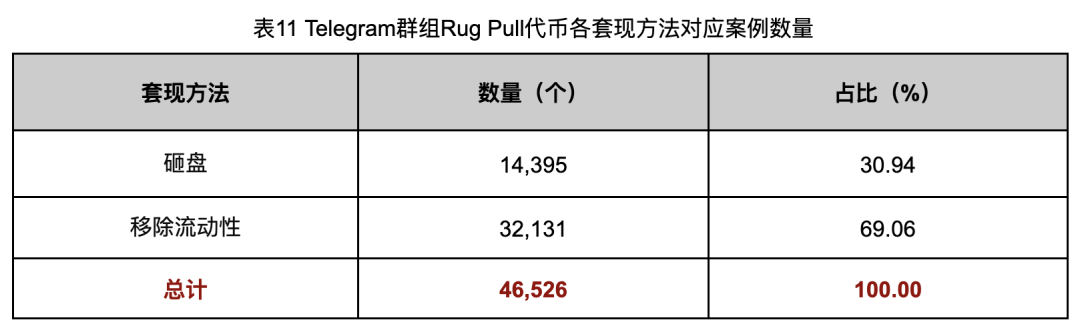

Cash-out method data is shown in Table 11.

Data shows 32,131 cases (69.06%) used liquidity removal for cash-out, suggesting preference for simplicity. In contrast, dumping requires pre-coded backdoors—more complex and risky—hence fewer instances.

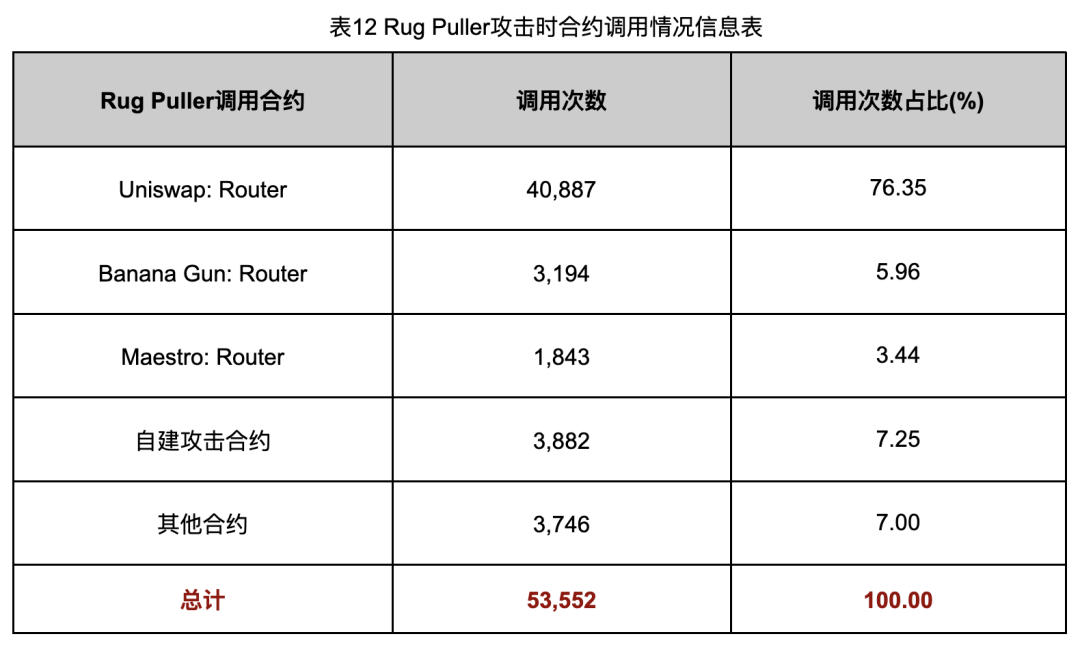

Contract interaction data is shown in Table 12.

Table 12 shows 40,887 (76.35%) Rug Pulls used Uniswap Router contracts. Total executions (53,552) exceed token count (46,526), indicating multiple pulls per case—possibly to maximize profit or stagger payouts.

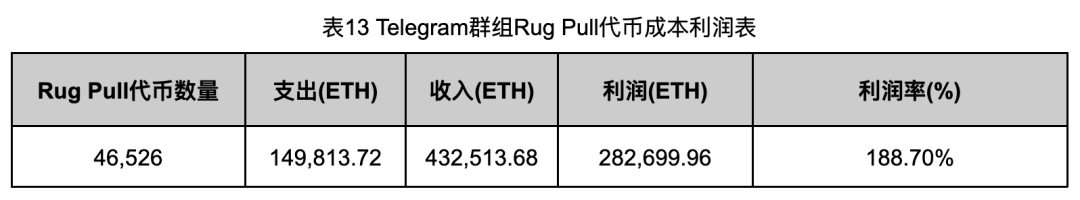

We also analyzed cost and revenue for the 46,526 Rug Pull cases. Costs are defined as ETH obtained by Deployers pre-deployment; revenues are ETH recovered during Rug Pulls. Self-generated volume costs were excluded, so actual costs may be higher.

Cost and revenue data is presented in Table 13.

Total profit reached 282,699.96 ETH (188.70% ROI), roughly $800 million. Actual profits may be slightly lower, but the scale remains staggering.

Telegram group data reveals a rampant presence of Rug Pull tokens in Ethereum’s ecosystem. But a key question remains: Do these groups cover all mainnet token launches? If not, what proportion do they represent?

Answering this will give us a holistic view of Ethereum’s token landscape. Thus, we proceed to analyze Ethereum mainnet token issuance to assess Telegram group coverage and better gauge the severity and influence of these promotion channels.

· Analyzing Mainnet-Issued Tokens

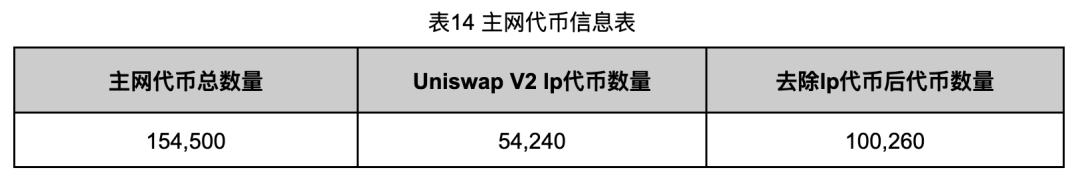

We scraped block data via RPC nodes for the same period (Oct 2023–Aug 2024), extracting newly deployed tokens (excluding proxy-based tokens, which rarely involve Rug Pulls). We captured 154,500 tokens, including 54,240 Uniswap V2 LP tokens—which we exclude from analysis.

After filtering LP tokens, we obtained 100,260 tokens. Details in Table 14:

We applied Rug Pull detection rules to these 100,260 tokens, results in Table 15:

Among 100,260 tokens, 48,265 (48.14%) were Rug Pulls—very close to the Telegram group ratio.

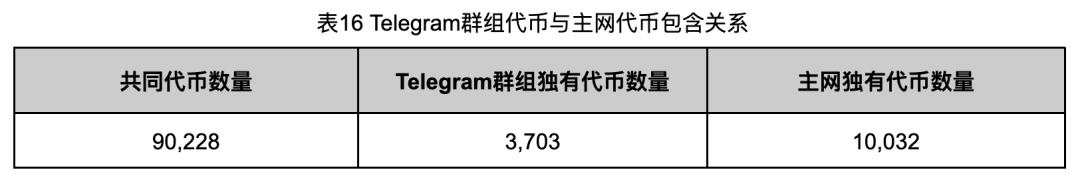

To analyze overlap between Telegram-promoted and mainnet tokens, we compared both datasets (Table 16):

Intersection: 90,228 tokens (89.99% of mainnet tokens). The 3,703 Telegram-only tokens are mostly proxy-based, excluded from our mainnet crawl.

The 10,032 mainnet tokens not promoted in Telegram groups may have been filtered due to low attractiveness or failing promotion criteria.

We separately tested the 3,703 proxy-based tokens and found only 10 Rug Pulls. Thus, proxy tokens minimally affect Telegram group analysis, confirming consistency between Telegram and mainnet Rug Pull rates.

The 10 proxy-based Rug Pull addresses are listed in Table 17 for reference.

Now we can answer: Do Telegram groups cover all mainnet token launches? If not, what’s their share?

Answer: Telegram groups promote ~90% of mainnet tokens, with near-identical Rug Pull ratios. Thus, Telegram data accurately reflects the overall Ethereum mainnet token ecosystem.

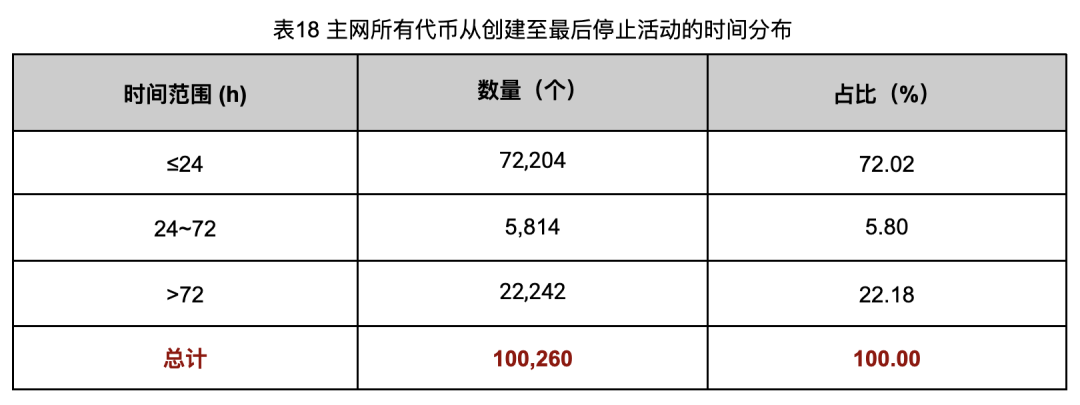

Earlier, we noted a 48.14% Rug Pull rate on Ethereum. But what about the remaining 51.86% non-Rug Pull tokens? Even excluding scams, 51,995 tokens remain unclassified—far exceeding reasonable expectations. So, we analyzed token lifespan (creation to final activity) across all mainnet tokens (Table 18):

Extending analysis to the full mainnet, 78,018 tokens (77.82%) had lifespans under 72 hours—significantly more than detected Rug Pulls. This indicates our detection rules don’t capture all scams. Sampling confirmed undetected Rug Pulls. It also suggests other fraud types exist—such as phishing or Ponzi schemes (“Pi Xiu” pools)—requiring further exploration.

Still, 22,242 tokens lasted over 72 hours. Though not our focus, they may include failed projects or legitimate ones lacking long-term support—each with complex underlying dynamics.

The Ethereum token ecosystem is far more intricate than imagined, with intertwined short- and long-term projects and endless scam variants. This report aims to raise awareness: unknown threats are always emerging. We hope this sparks further research to strengthen blockchain security.

Reflections

The 48.14% Rug Pull rate among newly issued Ethereum tokens is alarming. It means nearly every second new token is a scam, reflecting chaos and disorder in the current Ethereum ecosystem. Yet, the concern extends beyond Ethereum. Our monitoring systems have detected even more Rug Pull cases on other blockchains—what does their token landscape look like? This warrants deeper study.

Moreover, even excluding the 48.14% scam tokens, Ethereum still sees ~140 new tokens daily—well above sustainable levels. Are there hidden risks among these non-scam tokens? These questions demand deeper reflection.

Additionally, several key areas require further exploration:

1. How to efficiently identify the number and connections among Rug Pull gangs in the Ethereum ecosystem?

Given the volume of detected cases, how can we determine how many independent gangs exist and whether they’re interconnected? This may require combining fund flow and shared-address analysis.

2. How to more accurately distinguish victim addresses from attacker addresses in Rug Pull cases?

Distinguishing victims from attackers is crucial, yet boundaries are often blurred. Improving precision here is a critical research area.

3. Can Rug Pull detection be moved forward to real-time or pre-attack stages?

Current detection relies on post-mortem analysis. Can we develop real-time or predictive models to flag risks before exit events? Such capabilities would reduce losses and enable proactive intervention.

4. What are the Rug Pull gangs’ profit strategies?

Understanding thresholds for pulling the plug (e.g., average profit targets) and mechanisms ensuring profitability can help predict and prevent such attacks.

5. Beyond Twitter and Telegram, are there other promotion channels?

This report focuses on Twitter and Telegram, but could forums, social media, or ad platforms also be exploited? Do they pose similar risks?

These issues merit deep discussion. As Web3 evolves rapidly, ensuring its security requires not just technological advances but also comprehensive monitoring and rigorous research to counter evolving threats.

Recommendations

As highlighted, the current token launch ecosystem is rife with scams. Web3 investors must exercise extreme caution to avoid losses. As Rug Pull gangs and anti-fraud teams escalate their cat-and-mouse game, identifying malicious tokens grows increasingly difficult.

For investors interested in launch markets, our security experts offer the following guidance:

1. Prefer reputable centralized exchanges for new token purchases: Prioritize well-known CEXs, which enforce stricter project vetting and offer higher security.

2. When buying via DEXs, verify official websites and on-chain addresses: Ensure tokens come from verified contract addresses to avoid scams.

3. Before purchasing, confirm the project has an official website and active community: Projects lacking online presence are high-risk. Be especially cautious of tokens promoted via third-party Twitter or Telegram groups—most lack security validation.

4. Check token creation time; avoid tokens younger than 3 days: Technically capable users can inspect creation time via block explorers. Avoid tokens created less than 3 days ago, as Rug Pull tokens typically have very short lifespans.

5. Use third-party security scanning services: Where possible, leverage token audit tools from trusted security firms to assess safety.

Call to Action

Beyond the Rug Pull gangs studied here, growing numbers of criminals are exploiting Web3 infrastructure and mechanisms for illicit gain, worsening the ecosystem’s security crisis. We must start addressing commonly overlooked vulnerabilities to deny criminals opportunities.

As noted, Rug Pull funds eventually pass through major exchanges. But this visible flow is likely just the tip of the iceberg—the total volume of malicious funds traversing exchanges may be vastly underestimated. We strongly urge exchanges to implement stricter monitoring and actively combat fraud to safeguard user assets.

Third-party providers like launch promoters and sniper bots have inadvertently become enablers of fraud. We call on all such service providers to strengthen content and product security reviews to prevent misuse.

We also urge victims—including MEV searchers and retail users—to proactively use security scanning tools, consult authoritative project ratings, and publicly disclose malicious behaviors to expose industry wrongdoing.

As a professional security team, we call on all security practitioners to actively detect, identify, and confront malicious actors—speak up, and protect user assets.

In the Web3 space, users, projects, exchanges, MEV searchers, and third-party bot providers all play vital roles. We hope every participant contributes to building a safer, more transparent blockchain environment for sustainable growth.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News