Will Layer 2 networks be the endgame for Bitcoin scaling?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Will Layer 2 networks be the endgame for Bitcoin scaling?

A comprehensive guide to Layer 2 solutions such as sidechains, Lightning Network, RGB, and Rollups, as well as popular Bitcoin core community proposals like Drivechain and Spacechain.

Author: Chakra Research

In addition to the native scaling solutions covered in the first part, another approach to scaling Bitcoin involves building an additional protocol layer on top of Bitcoin, known as Layer 2. There are two critical aspects to Layer 2 solutions: secure two-way bridging and inheriting Bitcoin’s consensus security.

Sidechains

The concept of sidechains originated as early as 2014 with Blockstream's paper "Enabling Blockchain Innovations with Pegged Sidechains," proposing a relatively straightforward scaling solution.

How It Works

A sidechain is a blockchain that operates completely independently from the main chain, with its own consensus protocol, serving as an experimental ground for innovation on the main chain. If malicious events occur on the sidechain, the damage remains confined to the sidechain itself, without affecting the main chain. Sidechains can adopt consensus protocols with higher TPS and enhanced programmability to extend BTC functionality.

Sidechains can transfer Bitcoin between blockchains using either a two-way peg or one-way peg. In reality, BTC can only exist on the Bitcoin network, so an anchoring mechanism is required to link BTC on the sidechain with BTC on the Bitcoin network.

With a one-way peg, users send BTC from the mainnet to an unusable address for destruction, receiving an equivalent amount of BTC on the sidechain—but this process is irreversible. A two-way peg improves upon the one-way peg by allowing BTC to move back and forth between the main chain and sidechain. Instead of destroying BTC via sending to an unusable address, the two-way peg locks BTC using multisig or other control scripts, then mints new BTC on the sidechain. When users wish to return to the mainnet, they burn the BTC on the sidechain and unlock the originally locked BTC on the mainnet.

Implementing a one-way peg is significantly simpler than a two-way peg because it does not require managing states on the Bitcoin network. However, assets generated through a one-way peg may be worthless due to the lack of a reverse anchoring mechanism.

Verification of locking transactions on the main chain and burning transactions on the sidechain varies in approach and security level. The simplest method uses external validation by multisig participants, but carries high centralization risk. A better alternative is using SPV Proofs for decentralized verification. However, due to Bitcoin's limited programming capabilities, SPV verification cannot be performed directly on-chain, making multisig custody the usual choice.

Problems and Approaches

Two major criticisms of sidechains are:

Dependence on verifiers for cross-chain asset transfers: Since Bitcoin lacks smart contract functionality, trustless contract logic cannot handle cross-chain transfers. Returning BTC from a sidechain to Bitcoin requires reliance on a group of validators, introducing trust assumptions and fraud risks.

Sidechains cannot inherit main chain security: As sidechains operate independently, they do not inherit the main chain's security and may suffer malicious reorganizations.

To address these issues, various approaches have been proposed: relying on authorities (federated models), economic security (PoS), merged mining with decentralized Bitcoin miners, or hardware security modules (HSM). Custody of funds on Bitcoin and block production on the sidechain can be separated among different roles, enabling more complex security mechanisms.

Case Studies

Liquid

The earliest form of sidechain was the federated sidechain, where pre-selected entities serve as validators responsible for both mainnet fund custody and sidechain block production.

Liquid is a representative federated sidechain, with 15 participating parties acting as validators. Private key management methods are not publicly disclosed, and validation requires 11 signatures. Block production on the Liquid sidechain is also maintained collectively by these 15 parties. This low-node-count consortium chain achieves high TPS, fulfilling scalability goals, primarily targeting DeFi applications.

However, the federated model poses significant centralized security risks.

Rootstock (RSK)

RSK also uses 15 nodes for mainnet fund custody, requiring only 8 signatures for validation. Unlike Liquid, RSK manages multisig keys through Hardware Security Modules (HSM), which sign peg-out instructions based on PoW consensus, preventing key-holding validators from directly manipulating custodied funds.

For sidechain consensus, RSK employs Merged Mining, leveraging mainnet hash power to secure transactions on the sidechain. When merged mining accounts for a large proportion of total hash rate, double-spending attacks on the sidechain can be effectively prevented. RSK has improved Merged Mining to maintain security even under low hash rates, using a fork-aware method with off-chain consensus intervention to reduce double-spend probabilities.

Nevertheless, Merged Mining alters miner incentives and increases MEV risks, potentially undermining system stability. In the long term, it could lead to increased mining centralization.

Stacks

Stacks enhances security by submitting its block hashes into Bitcoin blocks, anchoring Stacks' chain history to Bitcoin and achieving the same finality. Forks on Stacks can only result from Bitcoin forks, improving resistance to double-spending.

sBTC introduces a new token STX and a staking-based bridge model, allowing up to 150 mainnet validators. Validators must stake STX tokens to gain permission to approve deposits and withdrawals. The security of this staking bridge heavily depends on the value of staked assets. During sharp fluctuations in staked asset value, cross-chain BTC security may be compromised. If the value of staked assets falls below that of the bridged assets, validators have incentive to act maliciously.

Several other sidechain proposals are currently under active discussion within the community.

Drivechain

The most discussed proposal is Drivechain, introduced by Paul Sztorc in 2015. Its key technologies have been assigned BIP 300 (pegging mechanism) and BIP 301 (blind merged mining). BIP 300 defines the logic for adding a new sidechain, with activation similar to soft forks via miner signaling. BIP 301 allows Bitcoin miners to produce sidechain blocks without verifying transaction details.

Miners also control withdrawal approvals. They first propose a withdrawal transaction by creating an OP_RETURN output in their coinbase transaction. Other miners can then vote on this proposal—each mined block allows supporting or opposing the withdrawal. Once a withdrawal receives sufficient votes over a threshold (13,150 blocks), it is executed and confirmed on the Bitcoin main chain.

Effectively, miners have full control over funds on Drivechain. In case of theft, users would need to resort to UASF (User-Activated Soft Fork) for自救, which is extremely difficult to coordinate. Additionally, Drivechain grants miners unique power, exacerbating MEV risks—a problem already observed on Ethereum.

Spacechain

Spacechain takes a different approach, using Perpetual One-Way Peg (P1WP): users burn BTC to obtain tokens on Spacechain, bypassing fund security concerns entirely. These tokens are solely used to bid for block space on Spacechain and hold no value storage function.

To ensure sidechain security, Spacechain uses blind merged mining. Other users compete via ANYPREVOUT (APO) to win the right to build blocks, while Bitcoin miners only commit to Spacechain block headers without validating sidechain blocks. However, launching Spacechain requires support for Covenants, and the Bitcoin community is still debating whether to add Covenant opcodes via soft fork.

Overall, Spacechain leverages Bitcoin-based bidding for block construction to create a sidechain with Bitcoin-level decentralization, censorship resistance, and greater programmability.

Softchain

Softchain is a 2wp sidechain proposal by Ruben Somsen, author of Spacechain, using PoW FP consensus to secure the sidechain. Under normal conditions, Bitcoin full nodes only download Softchain block headers and verify proof-of-work. During forks, orphaned blocks and corresponding UTXO set commitments are downloaded to validate block validity.

For the 2wp mechanism, a deposit transaction is created on the main chain during peg-in, and the Softchain references this transaction to receive funds. For peg-out, a withdrawal transaction is created on Softchain, and the main chain references it to reclaim BTC—this process requires a long challenge period before completion. Specific peg-in and peg-out mechanisms require soft fork support, hence the name Softchain.

The Softchain design imposes additional validation costs on Bitcoin full nodes. Consensus splits on Softchain could potentially affect mainnet consensus, posing a possible attack vector against Bitcoin.

Lightning Network

Introduced in a whitepaper in 2015 and launched in 2018, the Lightning Network is a peer-to-peer payment protocol operating as a Layer 2 solution on Bitcoin. It aims to move numerous small, frequent transactions off-chain and has long been considered the most promising scalability solution for Bitcoin.

Core Components

The implementation of the Lightning Network relies on several key features in Bitcoin, all contributing to its transaction security.

First is pre-signed transactions. These became secure and usable only after the SegWit upgrade. By separating signatures from other transaction data, SegWit resolved potential circular dependencies, third-party transaction tampering, and second-party tampering. The security of off-chain computations in Lightning is guaranteed by irrevocable commitments from counterparties, implemented through pre-signed transactions. Upon receiving a counterparty’s pre-signed transaction, a user can broadcast it on-chain at any time to enforce the commitment.

Second is multi-signature. Frequent off-chain fund transfers require a shared vehicle where both parties retain some control—typically achieved with 2-of-2 multisig, ensuring that fund transfers require mutual agreement.

However, 2-of-2 multisig introduces liveness issues—if one party refuses to cooperate, the other cannot retrieve funds from the multisig address, risking loss of capital. Time locks solve this issue by pre-signing a time-locked refund transaction, guaranteeing that even if one party becomes unresponsive, the other can reclaim their initial funds after a timeout.

Lastly, hash locks enable connecting multiple state channels into a network. The preimage of a hash serves as a communication medium, coordinating correct operation across multiple entities.

Operation Flow

Bidirectional Channel

Two parties using the Lightning Network must first open a bidirectional payment channel on Bitcoin. They can then conduct unlimited off-chain transactions, finally settling the latest state on-chain and closing the channel when done.

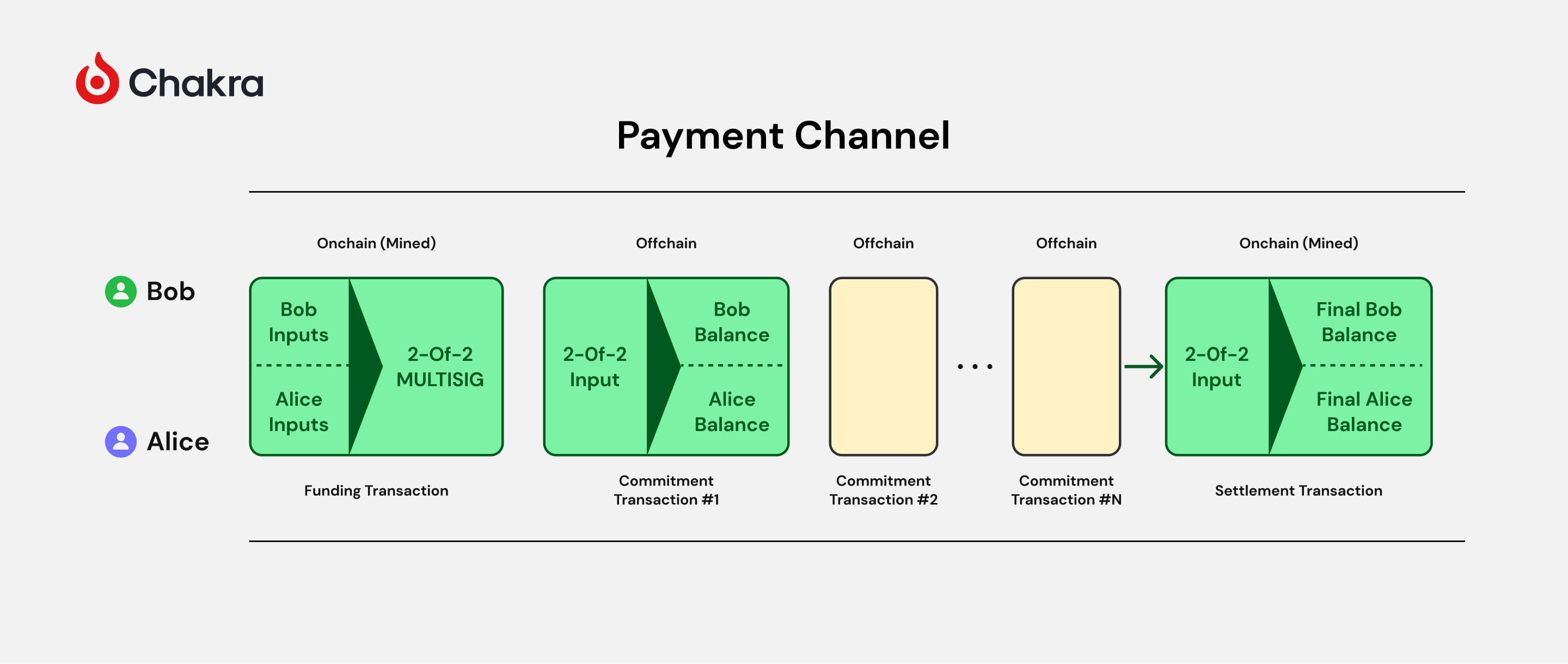

Specifically, implementing a payment channel involves the following key steps:

-

Create a multisig address. Both parties create a 2-of-2 multisig address as the funding lock address, each holding a private signing key and providing their public key.

-

Initialize the channel. Both parties broadcast a transaction on-chain, locking a certain amount of BTC into the multisig address as initial channel funds. This is known as the channel’s “anchor” transaction.

-

Update channel state. Off-chain payments are made by exchanging pre-signed transactions to update the channel state. Each update generates a new “commitment transaction” reflecting the current fund distribution, with two outputs corresponding to each party’s balance.

-

Broadcast latest state. Either party can broadcast the latest commitment transaction to extract their share. To prevent cheating with old states, each commitment transaction includes a corresponding “penalty transaction.” If the counterparty cheats, the honest party can claim their entire funds.

-

Close the channel. When both parties agree to close, they cooperatively generate a “settlement transaction” broadcasting the final fund distribution, releasing funds from the multisig address back to their personal addresses.

-

On-chain arbitration. If parties cannot agree on closure, either can unilaterally broadcast the latest commitment transaction, initiating on-chain arbitration. If no dispute arises within a set period (e.g., one day), funds are distributed according to the commitment transaction.

Payment Network

Payment channels can interconnect to form a network, supporting multi-hop routing via HTLCs. HTLC uses a hash lock as the primary condition and a time-locked signature payment as a fallback, allowing interaction around the preimage before the timelock expires.

When two users lack a direct channel, they can route payments through intermediate HTLCs. The preimage R plays a crucial role, ensuring atomicity of payments. Meanwhile, HTLC timelocks decrease along the path, giving each hop enough time to process and forward the payment.

Challenges

At its core, the Lightning Network avoids external trust assumptions in asset bridging through p2p state channels and uses timelock scripts to provide ultimate asset protection, offering fault tolerance. Users can exit unilaterally even if their counterparty goes offline. Thus, the Lightning Network holds high utility in payment scenarios, yet faces several limitations:

-

Channel capacity limits. Payment channel capacity is constrained by initially locked funds, restricting large-value payments beyond channel limits. This may hinder use cases like commodity trading.

-

Online and synchronous requirements. To promptly receive and forward payments, Lightning nodes must remain online. Prolonged downtime may cause missed state updates and desynchronization, posing challenges for individual users and mobile devices, increasing node operation costs.

-

Liquidity management. Routing efficiency depends on liquidity distribution across channels. Imbalanced funds may render some paths unusable, degrading user experience. Balancing channel liquidity requires technical and financial overhead.

-

Privacy leakage. Finding viable payment routes requires partial knowledge of channel capacities and connectivity, potentially exposing user privacy such as fund distribution and counterparties. Opening and closing channels may also reveal participant identities.

RGB

Inspired by Peter Todd’s concepts of client-side validation and one-time seals, RGB was first proposed by Giacomo Zucco in 2016 as a scalable, privacy-preserving Bitcoin Layer 2 protocol.

Core Concepts

Client-Side Validation

Blockchain validation involves broadcasting blocks of transactions so every node computes and verifies them. This creates a public good—network nodes collectively validate transactions submitted by individuals, incentivized by BTC fees. Client-side validation shifts focus to individuals: state validation is not globally executed but performed only by participants involved in specific state transitions. Only transacting parties validate the validity of state changes, significantly enhancing privacy, reducing node burden, and improving scalability.

One-Time Seal

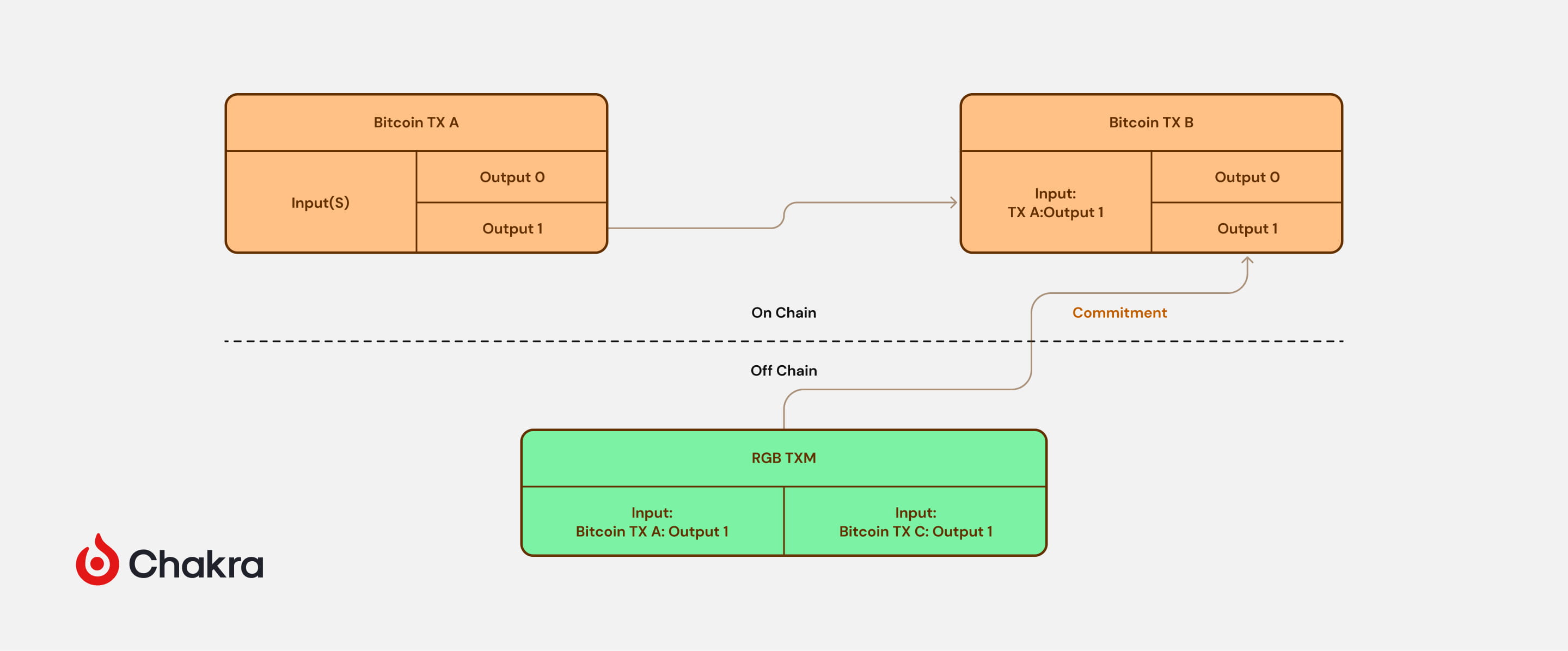

Peer-to-peer state transitions carry a risk: if users lack complete state transition history, they may fall victim to fraud or double-spending. The one-time seal concept addresses this by using a special object that can only be used once, preventing double-spending and improving security. Bitcoin’s UTXO is the ideal one-time seal object, secured by Bitcoin’s consensus and global hash power, allowing RGB assets to inherit Bitcoin’s security.

Commitments

One-time seals must be combined with cryptographic commitments to ensure users clearly recognize state transitions and avoid double-spending. A commitment informs others that an event has occurred and cannot later be altered, without revealing specifics until verification. Hash functions can be used for commitments. In RGB, the committed content is the state transition: when a UTXO is spent, the recipient receives a signal of state transfer and then validates the detailed off-chain data sent by the spender against the commitment.

Workflow

RGB leverages Bitcoin’s consensus to ensure double-spending resistance and censorship resistance, while delegating all state transition validation off-chain, exclusively to the receiving client.

For issuers of RGB assets, creating an RGB contract requires initiating a transaction whose details are committed within an OP_RETURN script inside a Taproot spending condition.

When an RGB asset holder wishes to spend, they must obtain information from the recipient, create an RGB transaction, commit its details, place the commitment into a UTXO specified by the recipient, and broadcast a transaction spending the original UTXO and creating the recipient’s designated UTXO. Once the recipient observes the UTXO containing the RGB asset being spent, they can verify the RGB transaction’s validity via the commitment in the Bitcoin transaction. Upon successful validation, they consider themselves to have received the RGB asset.

For recipients of RGB assets, the sender must provide: the initial contract state and state transition rules, each Bitcoin transaction used per transfer, the RGB transaction committed in each Bitcoin transaction, and evidence of each Bitcoin transaction’s validity. The recipient’s client uses this data to validate the RGB transaction. Here, Bitcoin UTXOs act as containers holding RGB contract states. Each RGB contract’s transfer history forms a directed acyclic graph, and recipients only access the branch relevant to their holdings, not others.

Advantages and Limitations

Lightweight Validation

Compared to full blockchain validation, RGB drastically reduces validation costs. Users don’t need to traverse all historical blocks to get the latest state; they only sync records related to their received assets to verify transaction validity.

This lightweight validation facilitates easier peer-to-peer transactions, further reducing reliance on centralized service providers and enhancing decentralization.

Scalability

RGB inherits Bitcoin’s security via a single hash commitment, using Taproot scripts to consume almost no additional on-chain space, enabling complex asset programmability. Using UTXOs as containers gives RGB natural concurrency—different branches of RGB assets do not block each other and can be spent simultaneously.

Privacy

Unlike typical protocols, only the recipient of an RGB asset can view its transfer history. After spending, they cannot see future transfers, significantly protecting user privacy. RGB transactions are not linked to Bitcoin UTXO movements, making it impossible for outsiders to detect RGB activity on-chain.

Additionally, RGB supports blinded spending, preventing senders from knowing which UTXO will receive the funds, further enhancing privacy and censorship resistance.

Limitations

After multiple transfers, new recipients may face long validation histories, leading to heavy verification burdens and longer confirmation times, losing fast finality. For continuously running blockchain nodes, synchronizing latest states means validation time for new blocks remains bounded.

The community is discussing reuse of historical computation, where recursive ZK proofs might enable constant-time and size state validation.

Rollups

Overview

Rollup emerged as the optimal scalability solution after years of exploration in the Ethereum ecosystem, evolving from state channels to Plasma and finally to Rollups.

A Rollup is an independent blockchain that collects transactions off the Bitcoin chain, batches and executes multiple transactions, then submits batch data and state commitments to the main chain, enabling off-chain transaction processing and state updates. To maximize scalability, Rollups often use centralized sequencers today to improve execution efficiency, while maintaining security through main-chain verification of Rollup state transitions.

As Ethereum’s Rollup solutions mature, the Bitcoin ecosystem has begun experimenting with Rollups. However, Bitcoin’s critical limitation—lack of programming capability—prevents performing necessary computations on-chain for Rollup construction, limiting current efforts to Sovereign Rollups and OP Rollups.

Classification

Based on how state transitions are verified, Rollups fall into two categories: Optimistic Rollups and Validity Rollups (ZK Rollups).

Optimistic Rollups use optimistic validation: during a dispute window after each batch submission, anyone can inspect off-chain data and submit fraud proofs to the main chain if invalid transactions are detected, slashing the Sequencer. If no valid fraud proof emerges after the window, the batch is deemed valid and state updates are confirmed on the main chain.

Validity Rollups use validity proofs: the Sequencer generates a succinct validity proof using zero-knowledge algorithms for each transaction batch, proving correct state transitions. Each update requires submitting the proof to the main chain, which verifies it before confirming the state change.

Optimistic Rollups are simpler to implement and require fewer main-chain modifications, but suffer from longer transaction finality times (dependent on dispute windows) and higher data availability requirements. Validity Rollups offer faster confirmation, no reliance on dispute windows, and can preserve transaction privacy, but generating and verifying ZK proofs demands significant computational resources.

Celestia also introduced Sovereign Rollups, where transaction data is published to a dedicated DA-layer blockchain for data availability, while the Sovereign Rollup handles execution and settlement.

Explorations and Discussions

Bitcoin Rollups are still in early stages. Due to differences in accounting models and programming languages compared to Ethereum, directly copying Ethereum’s practices is difficult. The Bitcoin community is actively exploring innovative approaches.

Sovereign Rollup

On March 5, 2023, Rollkit announced becoming the first framework supporting Bitcoin Sovereign Rollups, enabling builders to publish availability data onto Bitcoin.

Inspired by Ordinals, Rollkit publishes data via Taproot transactions. A standard mempool-compliant Taproot transaction can include up to 390 KB of data; non-standard Taproot transactions mined directly can include nearly 4 MB of arbitrary data.

Rollkit essentially provides an interface for reading and writing data to Bitcoin, offering middleware services that turn Bitcoin into a DA layer.

The idea of Sovereign Rollups has faced skepticism. Critics argue that such Rollups merely use Bitcoin as a bulletin board, failing to inherit Bitcoin’s security. Indeed, merely submitting transaction data to Bitcoin improves liveness—ensuring all users can retrieve data for validation—but security must be self-defined by the Rollup, not inherited. Moreover, Bitcoin block space is highly valuable; submitting full transaction data may not be a wise decision.

OP Rollup & Validity Rollup

Although many Bitcoin Layer 2 projects call themselves ZK Rollups, they are本质上 closer to OP Rollups, albeit involving Validity Proof technology. However, Bitcoin’s scripting capabilities are insufficient to natively verify Validity Proofs.

Currently, Bitcoin’s opcode set is very limited—even basic multiplication cannot be computed directly. Verifying Validity Proofs requires opcode expansion and heavily depends on covenant implementation. Community debates include proposals like OP_CAT, OP_CHECKSIG, OP_TXHASH, etc. Ideally, adding a single OP_VERIFY_ZKP might eliminate the need for other changes—but this seems unlikely. Additionally, stack size limits hinder attempts to verify Validity Proofs in Bitcoin scripts, though many experiments are underway.

So how do Validity Proofs work? Most projects publish transaction batch state diffs and Validity Proofs onto Bitcoin via inscriptions and use BitVM for optimistic verification. The BitVM bridge replaces traditional multisig schemes: Operators form an N-member alliance managing user deposits. Before depositing, users require alliance members to pre-sign the upcoming UTXO, ensuring only authorized Operators can claim deposited funds. After obtaining pre-signatures, BTC is locked into an N/N multisig Taproot address.

When a user requests withdrawal, the Rollup sends a Validity Proof containing the withdrawal root to Bitcoin. Operators front-fund the withdrawal, then validate correctness via BitVM contracts. If all Operators deem the proof valid, they reimburse the Operator via multisig; if any detects fraud, a challenge process initiates, slashing the dishonest party.

This process mirrors OP Rollup exactly, with a 1/N trust assumption: as long as one validator is honest, the protocol remains secure.

However, practical implementation may be challenging. In Ethereum’s OP Rollup projects, Arbitrum took years of development before Fraud Proofs were introduced—and they remain permissioned. Optimism only recently announced support for Fraud Proofs, illustrating the difficulty.

Pre-signing operations in BitVM bridges could be made more efficient with Bitcoin covenant support, pending community consensus.

From a security standpoint, submitting Rollup block hashes to Bitcoin provides resistance to reorgs and double-spends, while the optimistic bridge introduces a 1/N security assumption. However, bridge censorship resistance could still be improved.

Conclusion: Layer 2 Is Not a Panacea

Surveying these diverse Layer 2 solutions, it becomes clear that each has limited scope. The effectiveness of Layer 2 largely depends on Layer 1—Bitcoin’s native capabilities—under specific trust assumptions.

Without SegWit and timelocks, the Lightning Network couldn’t be built; without Taproot, RGB commitments wouldn’t be feasible; without OP_CAT and other covenants, Validity Rollups on Bitcoin would remain impossible…

Many Bitcoin Maximalists believe Bitcoin should never change or gain new features—all shortcomings should be solved by Layer 2. But this is unattainable. Layer 2 is not a panacea. We need a more powerful Layer 1 to build safer, more efficient, and scalable Layer 2 solutions.

Next, we’ll explore attempts to enhance programmability on Bitcoin. Stay tuned.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News