The Holy Grail of Bitcoin's Layer 2 Networks: Introspection and Covenants

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Holy Grail of Bitcoin's Layer 2 Networks: Introspection and Covenants

A Deep Dive into Popular Bitcoin Ecosystem Covenant Opcode Proposals: OP_CAT, CTV, APO, MATT

Author: Chakra Research

Overview

Compared to Turing-complete blockchains like Ethereum, Bitcoin's scripting system has long been considered highly restrictive—limited to basic operations and even lacking support for multiplication or division. More importantly, scripts cannot directly read blockchain data, severely limiting flexibility and programmability. As a result, the community has long sought ways to enable introspection in Bitcoin scripts.

Introspection refers to the ability of Bitcoin scripts to inspect and constrain transaction data. This allows scripts to control how funds are spent based on specific transaction details, enabling more complex functionality. Currently, most Bitcoin opcodes serve only two purposes: pushing user-provided data onto the stack or manipulating existing stack data. In contrast, introspection opcodes can push data from the current transaction—such as timestamps, amounts, or transaction IDs—onto the stack, allowing fine-grained control over UTXO spending.

Currently, Bitcoin script supports only three main introspection opcodes: CHECKLOCKTIMEVERIFY, CHECKSEQUENCEVERIFY, and CHECKSIG—with variants including CHECKSIGVERIFY, CHECKSIGADD, CHECKMULTISIG, and CHECKMULTISIGVERIFY.

A covenant, in simple terms, is a restriction on how a token can be transferred, allowing users to specify how a UTXO may be spent. Many covenants are implemented using introspection opcodes, and today Bitcoin Optech categorizes introspection under the broader topic of covenants.

Bitcoin currently has two covenants: CSV (CheckSequenceVerify) and CLTV (CheckLockTimeVerify), both time-based and foundational to many scaling solutions such as the Lightning Network. This highlights how Bitcoin’s scalability heavily relies on introspection and covenants.

How can we impose conditions on token transfers? In the crypto world, the most common method is commitment, typically achieved via hashing. To prove compliance with transfer rules, signature mechanisms are used for verification. Thus, covenants often involve adjustments to hash and signature logic.

Below, we describe several widely discussed covenant opcode proposals.

CTV (CheckTemplateVerify) BIP-119

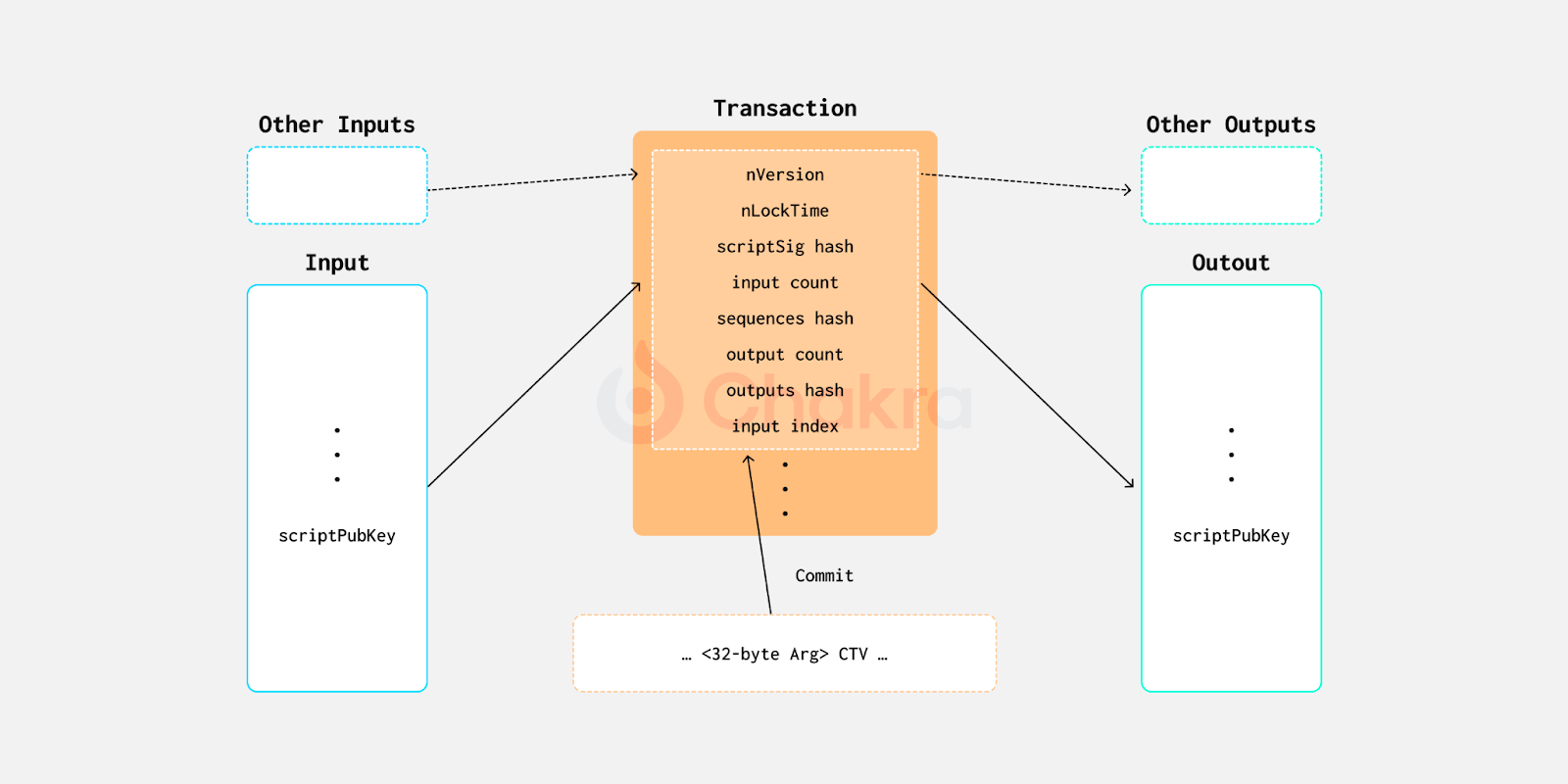

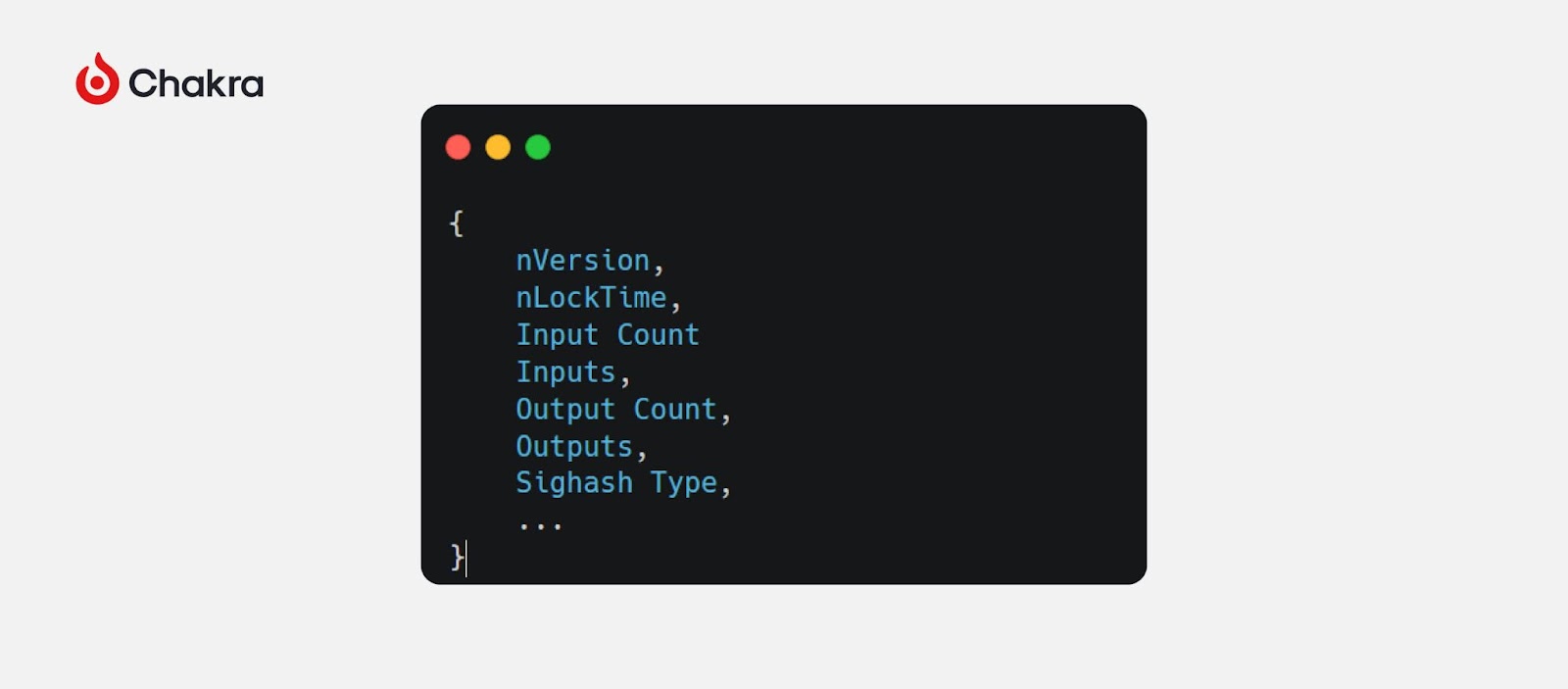

CTV (CheckTemplateVerify), specified in BIP-119, is a highly debated Bitcoin upgrade proposal. CTV enables an output script to define a template for future spending transactions, specifying fields such as nVersion, nLockTime, scriptSig hash, input count, sequences hash, output count, outputs hash, and input index. These constraints are enforced through a hash commitment. When the UTXO is later spent, the script verifies that the hash of the spending transaction's specified fields matches the committed hash, effectively locking down details like timing, structure, and amount of the future spend.

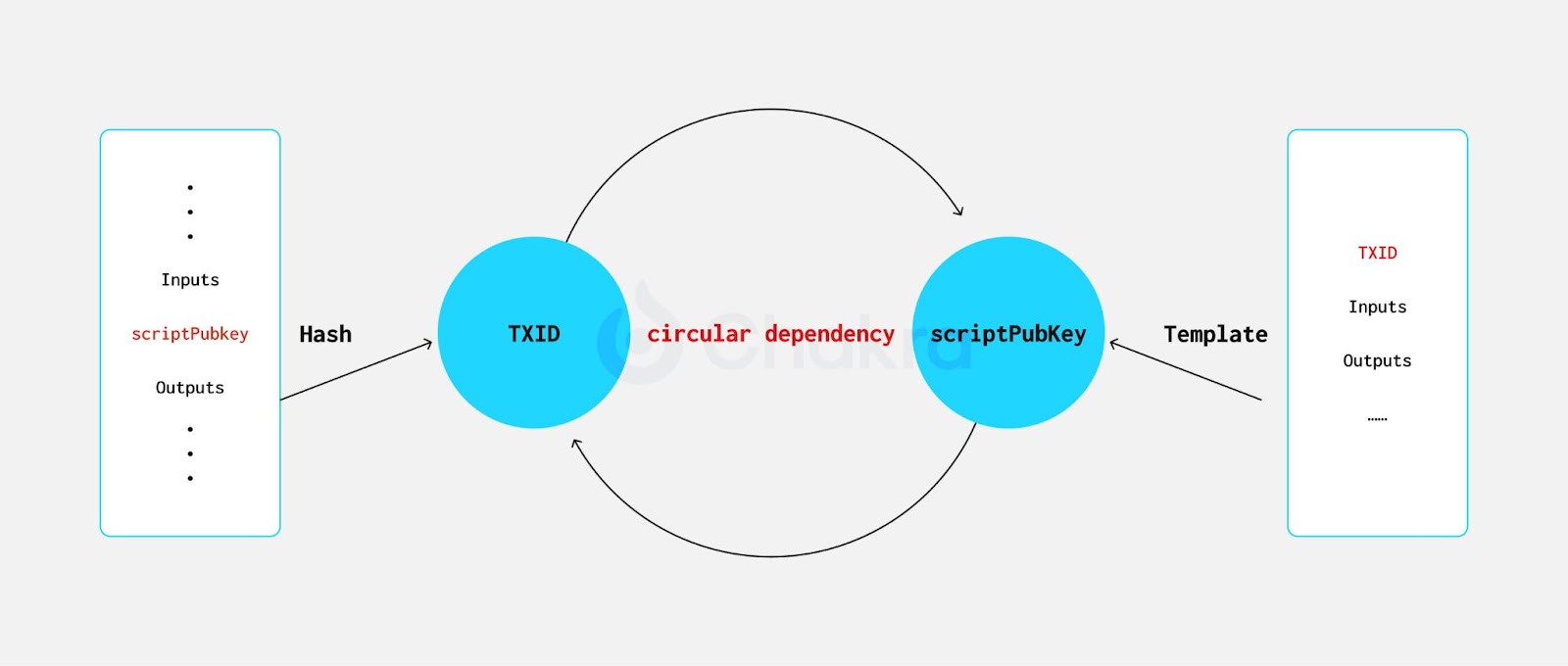

Notably, the input TXID is excluded from the hash commitment. This exclusion is necessary because, in both Legacy and SegWit transactions under the default SIGHASH_ALL signature type, the TXID depends on the value of scriptPubKey. Including TXID would create a circular dependency, making it impossible to construct the commitment.

CTV achieves introspection by using a new opcode to directly compute and hash specific transaction data, then comparing it against the committed hash on the stack. This approach consumes minimal on-chain space but offers limited flexibility.

Second-layer solutions like the Lightning Network rely on pre-signed transactions—transactions signed in advance but not broadcast until certain conditions are met. Fundamentally, CTV implements a stricter form of pre-signing by publishing the commitment directly on-chain, restricting spends to follow the predefined template exactly.

CTV was initially proposed to alleviate Bitcoin network congestion, also known as congestion control. During peak times, multiple future transactions can be committed via a single transaction, avoiding the need to broadcast numerous transactions when blocks are full. Actual settlement occurs later when congestion eases. Congestion control could be particularly useful during exchange bank runs. Additionally, templates can secure vaults against hacker attacks—since fund destinations are fixed, hackers cannot redirect UTXOs protected by CTV scripts to their own addresses.

CTV can significantly improve Layer 2 networks. For example, in implementing Timeout Trees and channel factories in the Lightning Network, a single UTXO can expand into a CTV tree, opening multiple state channels with only one on-chain transaction and confirmation. Furthermore, CTV supports atomic transactions (ATLC) in Ark protocols.

APO (SIGHASH_ANYPREVOUT) BIP-118

BIP-118 introduces a new signature hash flag for Tapscript called SIGHASH_ANYPREVOUT (APO), enabling more flexible spending logic. APO shares similarities with CTV; to resolve the circular dependency between scriptPubKeys and TXIDs, APO excludes input-related information and signs only the outputs, allowing dynamic binding to different UTXOs.

Logically, signature verification opcodes like OP_CHECKSIG (and its variants) perform three functions:

-

Assembling parts of the spending transaction

-

Hashing them

-

Verifying whether the hash was signed by a given key

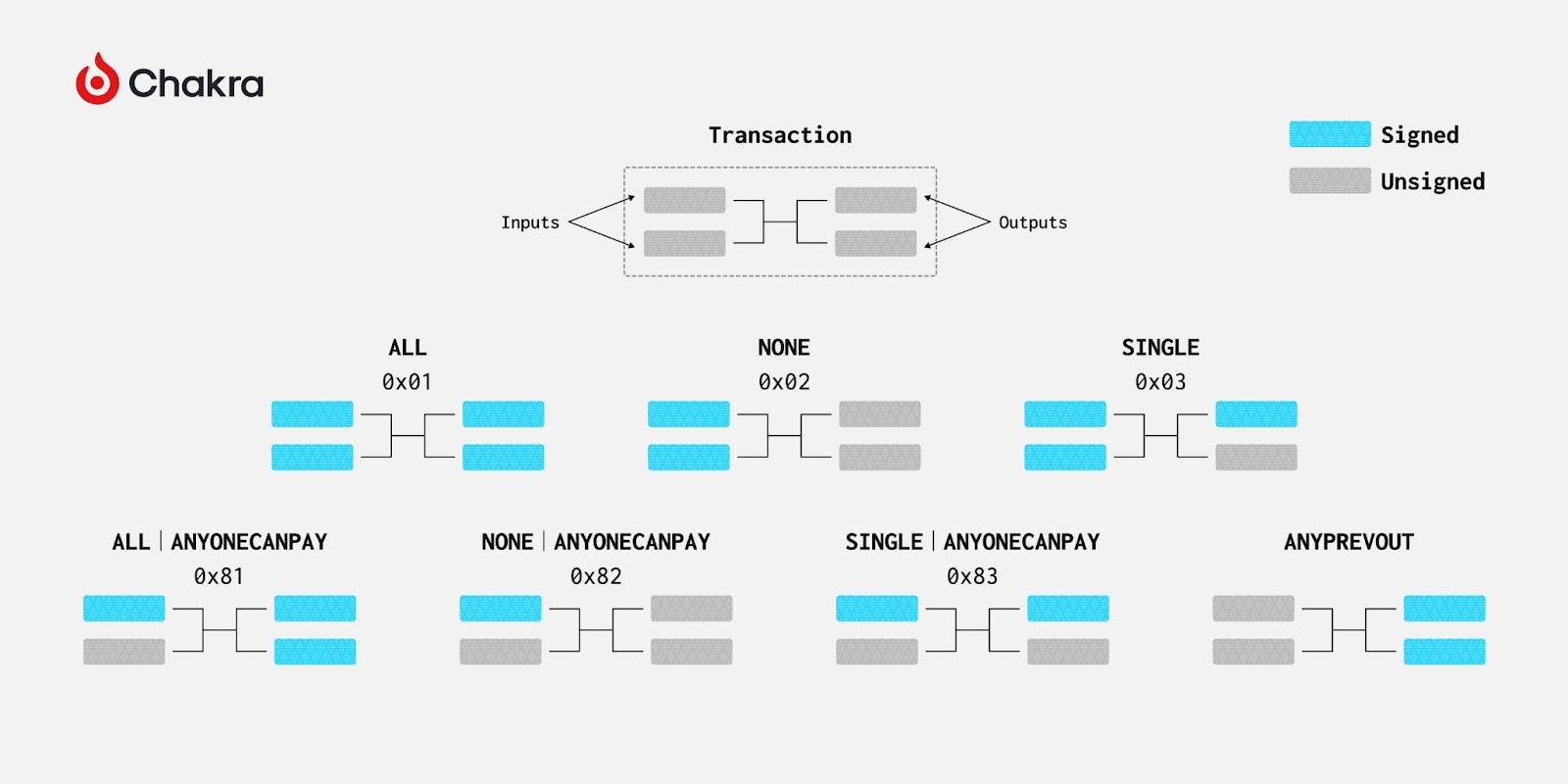

The specific content being signed can vary significantly depending on the SIGHASH flag, which determines which transaction fields are included. According to BIP 342, SIGHASH flags include SIGHASH_ALL, SIGHASH_NONE, SIGHASH_SINGLE, and SIGHASH_ANYONECANPAY. Among these, SIGHASH_ANYONECANPAY controls inputs, while the others govern outputs.

SIGHASH_ALL is the default, signing all outputs; SIGHASH_NONE signs no outputs; SIGHASH_SINGLE signs only one designated output. SIGHASH_ANYONECANPAY can be combined with the first three flags. If set, it signs only the specified input; otherwise, all inputs must be signed.

Clearly, none of these SIGHASH flags eliminate input commitments entirely—even SIGHASH_ANYONECANPAY requires committing to at least one input.

Thus, BIP-118 proposes SIGHASH_ANYPREVOUT. APO signatures do not commit to the specific input UTXO (PREVOUT) being spent, requiring only output commitments. This provides greater flexibility in controlling Bitcoin. By pre-building transactions and corresponding one-time-use signatures and public keys, assets sent to such keys can only be spent via the predefined transaction, forming a covenant. APO’s flexibility also enables transaction fee bumping—if a transaction gets stuck due to low fees, another version with higher fees can be created without needing new signatures. For multisig wallets, independence from input commitments simplifies operations.

By removing the circular dependency between scriptPubKeys and input TXIDs, APO enables introspection by adding output data to the witness. However, this still incurs additional witness data costs.

For off-chain protocols like Lightning and vaults, APO reduces the number of intermediate states that must be stored, greatly lowering storage needs and complexity. A primary use case for APO is Eltoo, which simplifies channel factories, enables lightweight and affordable watchtowers, and allows unilateral exits without leaving invalid states—improving overall Lightning performance. APO can simulate CTV functionality, though it requires storing individual signatures and pre-signed transactions, making it costlier and less efficient than CTV.

Criticism of APO centers on its requirement for a new key version, preventing pure backward compatibility. Additionally, new signature hash types may introduce potential double-spend risks. After extensive community discussion, APO now mandates inclusion of a regular signature alongside the APO signature, mitigating security concerns and earning it the BIP-118 designation.

OP_VAULT BIP-345

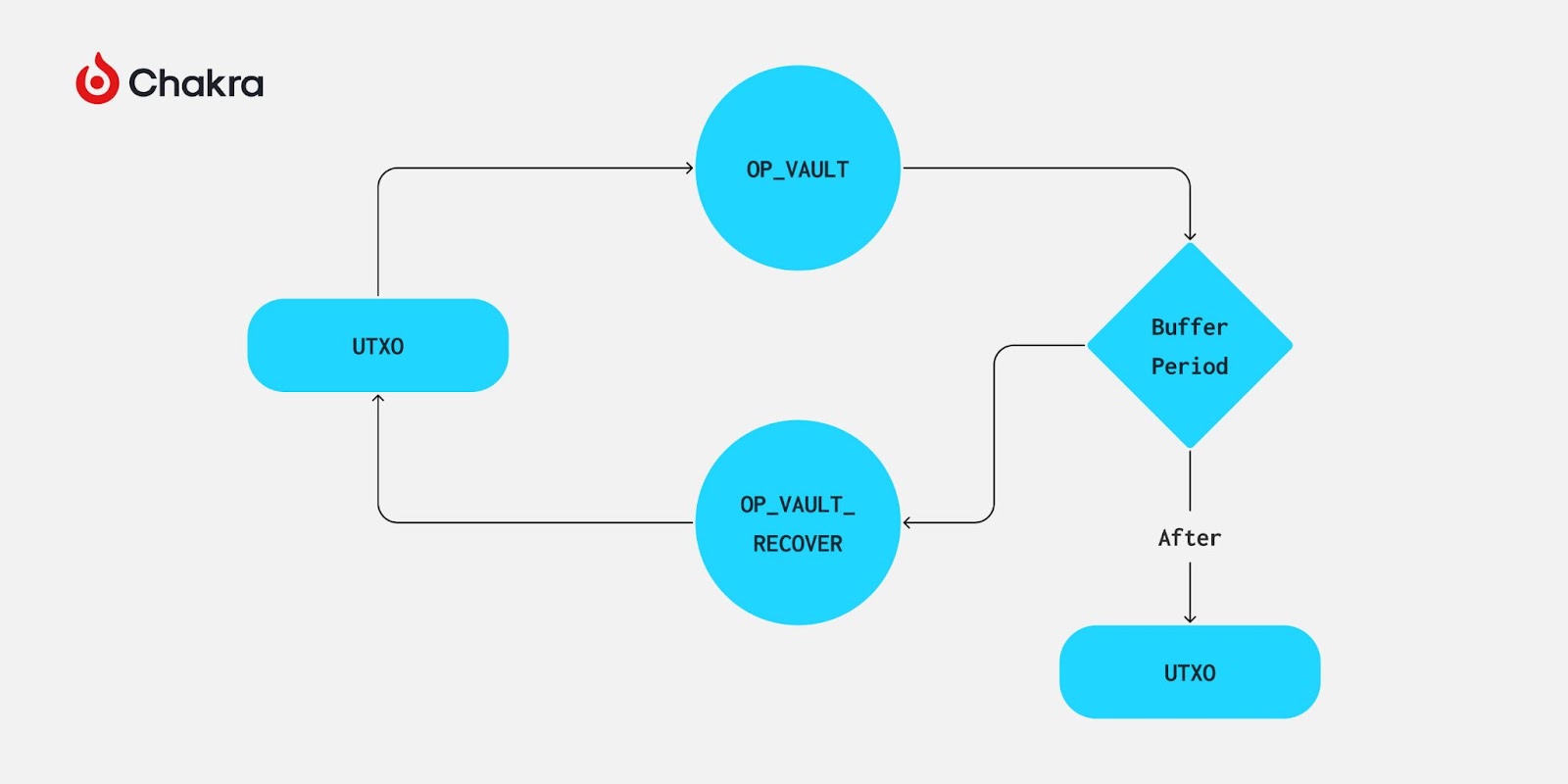

BIP-345 proposes two new opcodes, OP_VAULT and OP_VAULT_RECOVER, designed to work with CTV to implement a specialized covenant. It allows users to enforce a mandatory delay period on spending specific coins, during which the spend can be "reversed" via a recovery path.

Users can create a vault by generating a specific Taproot address containing at least two scripts within a MAST: one with OP_VAULT to facilitate intended withdrawals, and another with OP_VAULT_RECOVER to allow coin recovery at any point before withdrawal completes.

How does OP_VAULT achieve interruptible time-locked withdrawals? Simply put, the OP_VAULT opcode replaces the executed OP_VAULT script with a specified script—effectively updating a single leaf node in the MAST while leaving others unchanged. Its design resembles TLUV, except OP_VAULT does not support internal key updates.

Introducing templates during script updates enables restricted payments. The timelock parameter is defined by OP_VAULT, while the CTV opcode restricts the set of outputs that can be spent through this script path via templating.

BIP-345 is built specifically for vaults. With OP_VAULT and OP_VAULT_RECOVER, users gain a secure custody mechanism—using a high-security key (e.g., paper wallet or distributed multisig) as the recovery path, while setting up daily spending with a spending delay. Users’ devices continuously monitor vault activity and can recover funds if unauthorized transfers occur.

Implementing vaults under BIP-345 requires addressing fee concerns, especially for recovery transactions. Potential solutions include CPFP, temporary anchors, and new signature hash flags like SIGHASH_GROUP.

TLUV (TapleafUpdateVerify)

The TLUV proposal builds around Taproot to solve the problem of efficient exits from shared UTXOs. Its core idea is that when a Taproot output is spent, we can apply update steps described in the TLUV script—leveraging Taproot’s internal structure and cryptographic transformations—to partially update the internal key and MAST, thereby enabling covenant functionality.

TLUV introduces a new opcode TAPLEAF_UPDATE_VERIFY, which can create a new Taproot address based on the current spending input by performing one or more of the following actions:

-

Updating the internal public key

-

Pruning the Merkle path

-

Removing the currently executing leaf node

-

Adding a new leaf node at the end of the Merkle path

Specifically, TLUV takes three inputs:

-

One specifying how to update the internal public key

-

One specifying a new leaf node for the Merkle path

-

One indicating whether to remove the current leaf node and/or how many Merkle path nodes to prune

The TLUV opcode computes the updated scriptPubKey and verifies that the corresponding output in the current input spends to this scriptPubKey.

TLUV is inspired by CoinPool (joint pooling). Today, joint pools can be created using pre-signed transactions, but achieving permissionless exits requires exponentially growing numbers of signatures. TLUV enables permissionless exits without any pre-signing. For example, a group uses Taproot to build a shared UTXO pooling their funds. They can move money internally using Taproot keys or jointly sign external payments. Individuals can exit anytime by removing their payment path, while others retain access via original paths—without exposing additional internal information. Compared to non-pooled transactions, this approach is more efficient and private.

While TLUV achieves partial spending restrictions via MAST updates, it lacks output amount introspection. Therefore, an additional opcode IN_OUT_AMOUNT is needed, which pushes two values onto the stack: the amount of the input UTXO and the corresponding output amount. Users leveraging TLUV would then apply mathematical operators to verify proper fund retention in the updated scriptPubKey.

Output amount introspection adds complexity since Bitcoin amounts require up to 51 bits when expressed in satoshis, but script only supports 32-bit arithmetic. This necessitates redefining opcode behaviors to support larger math or replacing IN_OUT_AMOUNT with alternatives like SIGHASH_GROUP.

TLUV holds promise for decentralized Layer 2 pooling solutions, though reliability in tweaking Taproot public keys remains to be confirmed.

MATT

MATT (Merkleize All The Things) aims to achieve three goals: Merkleizing state, Merkleizing scripts, and Merkleizing execution—ultimately enabling general-purpose smart contracts on Bitcoin.

Merkleized State: Construct a Merkle Trie where each leaf is a hash of some state, and the Merkle Root represents the entire contract state.

Merkleized Script: Use Tapscript-based MAST, where each leaf represents a possible state transition path.

Merkleized Execution: Achieve via cryptographic commitments and fraud challenge mechanisms. For any computation function, participants compute off-chain and publish a commitment f(x)=y. If another participant detects an error f(x)=z, they can challenge it, triggering binary search arbitration—similar to Optimistic Rollups.

Fraud Challenge in Merkleized Execution

To implement MATT, Bitcoin scripting needs the following capabilities:

-

Enforce that an output has a specific script (and amount)

-

Attach arbitrary data to an output

-

Read data from the current input (or other inputs)

The second point is crucial—dynamic data means state can be computed from input data provided by spenders, enabling simulation of state machines and determination of next states and attached data. MATT achieves this via a proposed opcode OP_CHECKCONTRACTVERIFY (OP_CCV), merging earlier proposals OP_CHECKOUTPUTCONTRACTVERIFY and OP_CHECKINPUTCONTRACTVERIFY, with a flags parameter specifying the target.

Controlling output amounts: The most direct way is via direct introspection, but output amounts are 64-bit integers, requiring 64-bit arithmetic—which is complex in Bitcoin script. CCV uses deferred checking, similar to OP_VAULT: all inputs to the same output with CCV have their amounts summed, setting a minimum for the output amount. The check is delayed until transaction processing, not during script evaluation.

Given the generality of fraud proofs, certain variants of MATT covenants could support all types of smart contracts or Layer 2 constructions, though additional requirements (e.g., capital lockup and challenge delays) need careful assessment. Further research is needed to evaluate which applications are viable. For instance, simulating OP_ZK_VERIFY via cryptographic commitments and fraud challenges could enable trustless rollups on Bitcoin.

In fact, progress is already underway. Johan Torås Halseth used the OP_CHECKCONTRACTVERIFY opcode from the MATT soft fork proposal to implement elftrace, enabling verification of any program compilable to RISC-V on Bitcoin, allowing one party in a contract to claim funds after validation—achieving native Bitcoin-verified bridging.

CSFS (OP_CHECKSIGFROMSTACK)

From our discussion of APO, we know OP_CHECKSIG (and related ops) assemble the transaction, hash it, and verify the signature. However, the message being verified is implicitly derived from serializing the spending transaction—it cannot be arbitrarily specified. In short, OP_CHECKSIG protects Bitcoin’s security by verifying that the UTXO input is authorized for spending by the signer.

CSFS, as the name suggests, checks signatures from the stack. The CSFS opcode takes three stack arguments: a signature, a message, and a public key, and verifies the signature’s validity. This allows arbitrary messages to be passed via witness data and validated via CSFS, unlocking novel possibilities on Bitcoin.

CSFS’s flexibility enables mechanisms like payment signatures, delegation, oracle contracts, double-spend protection bonds—and crucially, transaction introspection. The principle is simple: if the transaction content used by OP_CHECKSIG is pushed onto the stack via witness, and both CSFS and OP_CHECKSIG verify it using the same key and signature, then the message passed to CSFS matches the implicit serialized spending transaction. We thus obtain verified transaction data on the stack, which can be used with other opcodes to constrain the spending transaction.

CSFS often appears with OP_CAT, since OP_CAT can concatenate transaction fields for serialization, enabling precise selection of introspected fields. Without OP_CAT, scripts cannot recompute hashes from separately checked data, limiting usage to exact hash equality—meaning coins can only be spent via one specific transaction.

CSFS can emulate CLTV, CSV, CTV, APO, and other opcodes, making it a universal introspection opcode—and thus beneficial for Bitcoin Layer 2 scaling. Its drawback is requiring a full copy of the signed transaction on the stack, potentially increasing transaction size significantly. In contrast, single-purpose introspection opcodes like CLTV and CSV are minimally costly, though each new special opcode requires consensus changes.

TXHASH (OP_TXHASH)

OP_TXHASH is a straightforward introspection opcode that pushes the hash of a selected transaction field onto the stack. Specifically, OP_TXHASH pops a txhash flag from the stack, computes the corresponding (tagged) txhash based on the flag, and pushes the resulting hash onto the stack.

Due to similarities between TXHASH and CTV, there has been significant debate within the community.

TXHASH can be seen as a generalized upgrade of CTV, offering a more advanced transaction template that allows users to explicitly fix parts of the spending transaction—addressing many fee-related issues. Compared to other covenant opcodes, TXHASH does not require duplicating required data in the witness, further reducing storage needs. Unlike CTV, TXHASH is not NOP-compatible and can only be implemented in tapscript. Combined with CSFS, TXHASH can serve as an alternative to both CTV and APO.

In terms of covenant construction, TXHASH facilitates "additive covenants"—pushing all desired fixed transaction components onto the stack, hashing them together, and verifying against a fixed value. CTV favors "subtractive covenants"—pushing free (variable) components onto the stack, then incrementally hashing them into a fixed intermediate state (a prefix commitment) using rolling OP_SHA256.

The TxFieldSelector field defined in TXHASH’s specification could extend to other opcodes, such as OP_TX.

The BIP related to TXHASH is currently in Draft status on GitHub, without a finalized number.

OP_CAT

OP_CAT is a mysterious opcode—originally removed by Satoshi due to security concerns, recently revived in discussions among core Bitcoin developers, sparking internet memes, and ultimately approved as BIP-347, hailed by many as the most likely BIP to be activated soon.

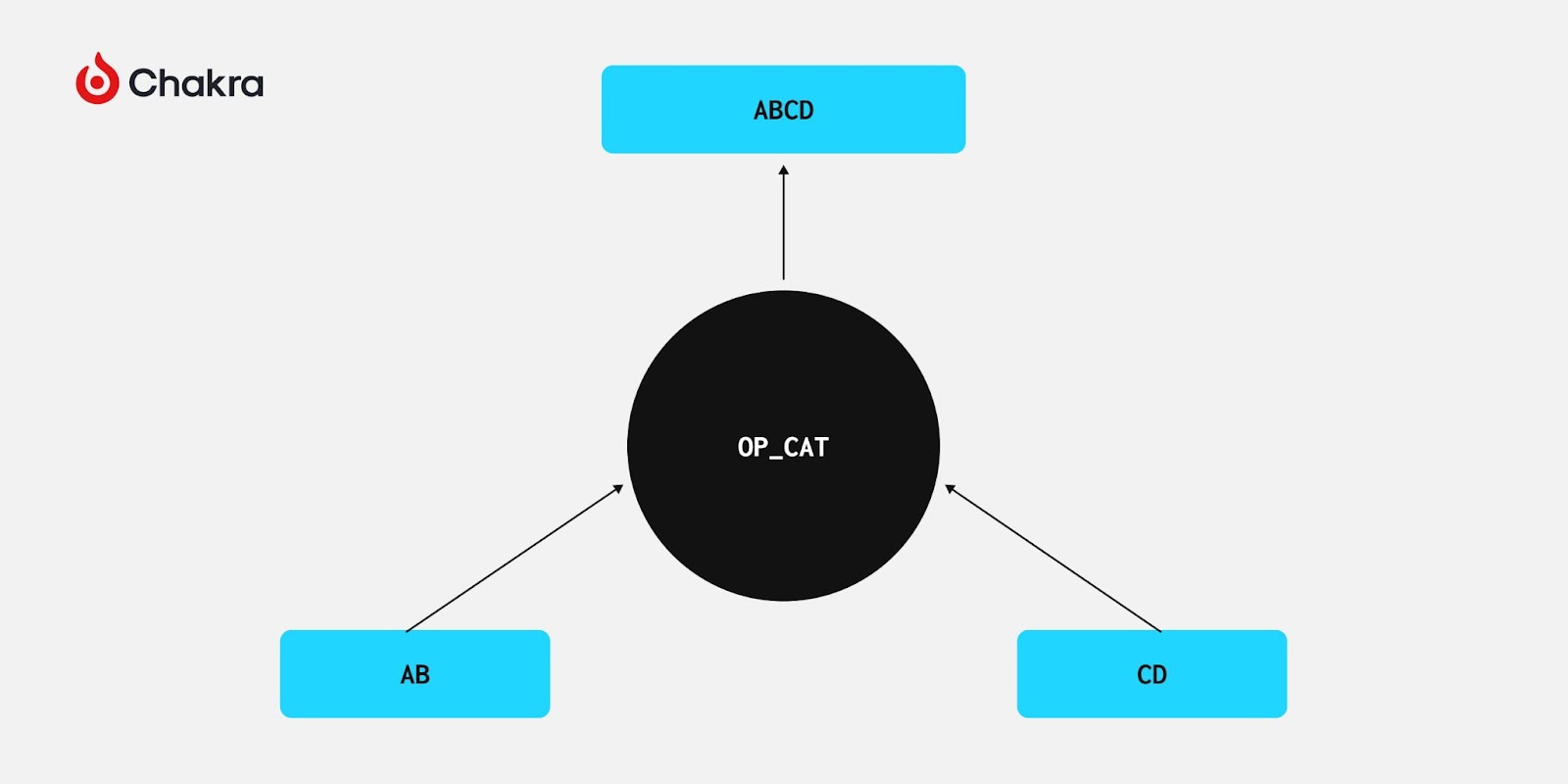

In reality, OP_CAT’s behavior is simple: it concatenates the top two stack elements into one. How does this enable covenants?

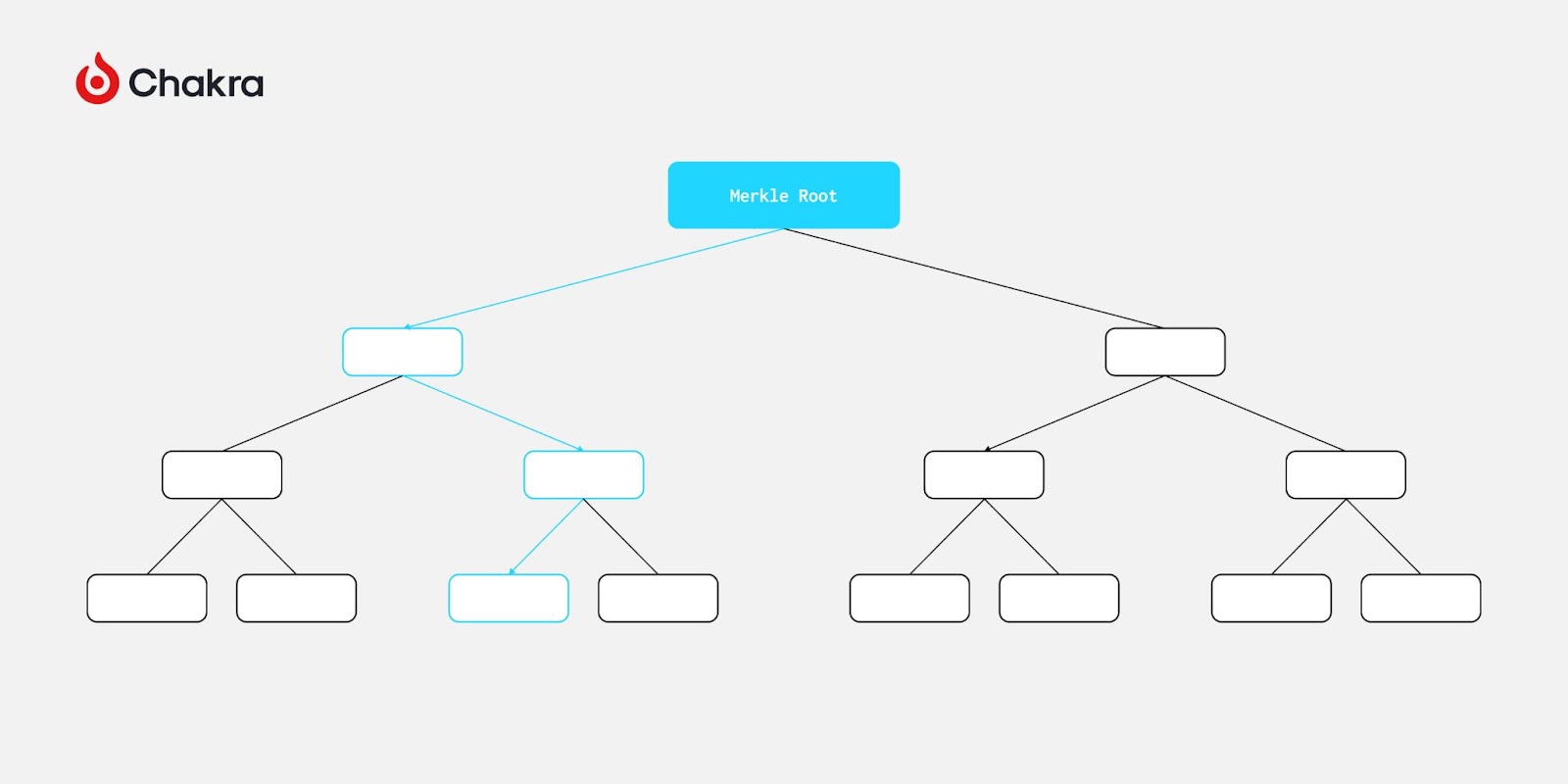

Concatenation enables a powerful cryptographic data structure: the Merkle Trie. Building a Merkle Trie requires only concatenation and hashing—both feasible in Bitcoin script since hash functions exist. With OP_CAT, we can theoretically verify Merkle Proofs in Bitcoin script, the most common lightweight verification method in blockchains.

As previously mentioned, CSFS leverages OP_CAT to enable general covenant schemes. In fact, even without CSFS, OP_CAT alone—combined with Schnorr signature structure—can achieve transaction introspection.

In Schnorr signatures, the message to be signed consists of the following fields:

These fields contain the main elements of a transaction. By placing them in scriptPubKey or witness and using OP_CAT and OP_SHA256, we can reconstruct a Schnorr signature and validate it via OP_CHECKSIG. If verification succeeds, the stack contains verified transaction data, enabling introspection—extracting and "inspecting" parts like inputs, outputs, destination addresses, or bitcoin amounts involved.

For detailed cryptographic principles, refer to Andrew Poelstra’s article “CAT and Schnorr Tricks.”

In summary, OP_CAT’s flexibility allows it to simulate nearly any covenant opcode, and many covenant proposals depend on OP_CAT’s functionality—significantly boosting its priority in the merge queue. Theoretically, using only OP_CAT and existing Bitcoin opcodes, we could build a minimally-trusted BTC ZK Rollup. Starknet, Chakra, and other ecosystem partners are actively advancing this vision.

Conclusion

As we explore various strategies to scale Bitcoin and enhance its programmability, it becomes clear that the path forward involves a combination of native improvements, off-chain computation, and sophisticated scripting capabilities.

Without a flexible base layer, building flexible second layers is impossible.

Off-chain computation is the future of scaling, but Bitcoin’s programmability must break through to better support scalability and become a true global currency.

However, Bitcoin’s computation differs fundamentally from Ethereum’s. Bitcoin only supports “verification” as a computational form—not general computation—whereas Ethereum is inherently computational, with verification as a byproduct. One key difference illustrates this: Ethereum charges gas fees for failed transactions, while Bitcoin does not.

Covenants represent a form of smart contract based on verification rather than computation. Regarding covenants, aside from a few Satoshi purists, nearly everyone agrees they are a promising direction for improving Bitcoin. Yet, the community remains divided on which specific proposal should be adopted.

APO, OP_VAULT, and TLUV lean toward direct applications—choosing them enables cheaper, more efficient implementation of specific use cases. Lightning enthusiasts favor APO for enabling LN-Symmetry; those building vaults prefer OP_VAULT; CoinPool builders benefit from TLUV’s privacy and efficiency. OP_CAT and TXHASH are more general-purpose, potentially safer (fewer attack vectors), and combinable with other opcodes for broader use cases—though possibly at the cost of script complexity. CTV and CSFS modify blockchain processing: CTV enables deferred outputs, CSFS enables deferred signatures. MATT stands apart, applying optimistic execution and fraud proofs with Merkle Trie structures to achieve general smart contracts—but still requires new opcodes for introspection.

We see intense debate within the Bitcoin community about enabling covenants via soft fork. Starknet has officially entered the Bitcoin ecosystem, planning settlement on Bitcoin within six months of OP_CAT activation. Chakra will continue monitoring the latest developments in the Bitcoin ecosystem, advocate for the OP_CAT soft fork, and leverage introspection and covenants to build a more secure and efficient Bitcoin settlement layer.

Thanks to Jeffrey, Ben, Mutourend, and Lynndell for their review and suggestions on this article.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News