Analyzing Why Plasma Does Not Support Smart Contracts: Data Withholding and Fraud Proofs

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Analyzing Why Plasma Does Not Support Smart Contracts: Data Withholding and Fraud Proofs

Plasma cannot solve the data withholding problem, nor does it facilitate migrating contract state to Layer 1, and will inevitably be abandoned.

Author: Faust, Geeker Web3

The reasons why Plasma has long been overshadowed and why Vitalik strongly supports Rollup mainly come down to two points: achieving DA off-chain on Ethereum is unreliable and prone to data withholding attacks; once data is withheld, fraud proofs become difficult to execute. The design of Plasma itself is extremely unfriendly to smart contracts, especially when it comes to migrating contract states to Layer1. These two issues essentially limit Plasma to using UTXO or similar models.

To understand these two core arguments, let's start with DA and the data withholding problem. DA stands for Data Availability—the literal translation being "data availability," which is now widely misused, often confused with "historical data accessibility." However, "historical data accessibility" and "proof of storage" are problems already solved by projects like Filecoin and Arweave. According to the Ethereum Foundation and Celestia, the DA problem specifically refers to scenarios involving data withholding.

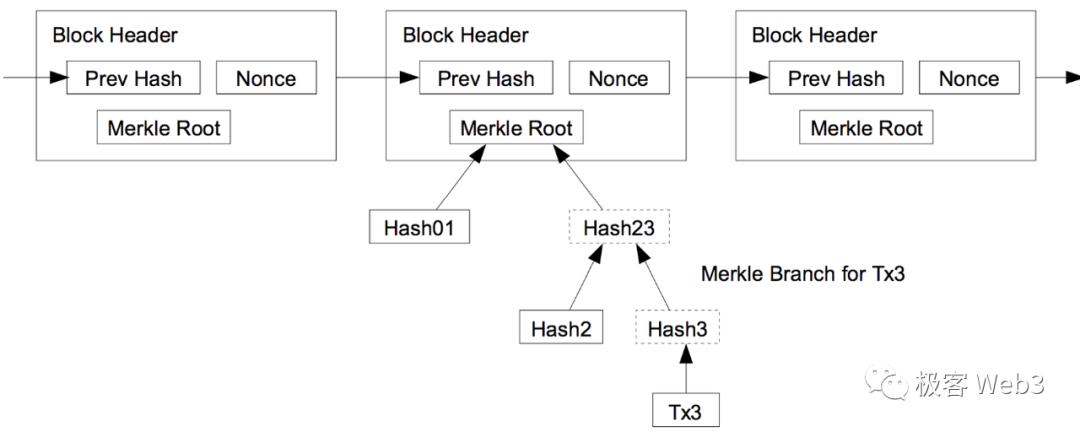

Merkle Tree, Merkle Root, and Merkle Proof

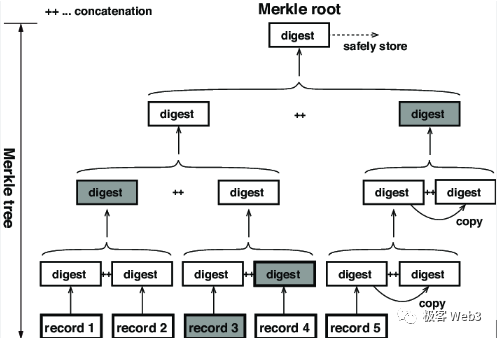

To clarify what data withholding attacks and the DA problem actually mean, we first need a brief explanation of Merkle Root and Merkle Tree. In Ethereum and most public blockchains, a tree-like data structure called a Merkle Tree serves as a summary/directory of all account states or records all transactions within each block.

The leaf nodes at the bottom of the Merkle Tree consist of hashes of raw data such as transactions or account states. These hashes are paired and combined iteratively until a single Merkle Root is computed.

(The "record" at the bottom of the diagram represents the original dataset corresponding to the leaf nodes)

Merkle Root has one key property: If any leaf node at the base of the Merkle Tree changes, the resulting Merkle Root will also change. Therefore, different datasets produce different Merkle Roots—much like how different people have unique fingerprints. The verification technique known as Merkle Proof leverages this property of Merkle Trees.

Taking the above diagram as an example, suppose Li Gang only knows the value of the Merkle Root in the figure but does not know the full Merkle Tree or its underlying data. We want to prove to Li Gang that Record 3 is indeed associated with this Root—that is, to prove that the hash of Record 3 exists within the Merkle Tree corresponding to this Root.

We only need to submit Record 3 and the three digest blocks marked gray in the image to Li Gang—not the entire Merkle Tree or all its leaves. This is the succinctness of Merkle Proof. When the Merkle Tree contains a large number of leaf entries—for example, 2^20 (about one million) data blocks—the Merkle Proof requires as few as 21 data blocks.

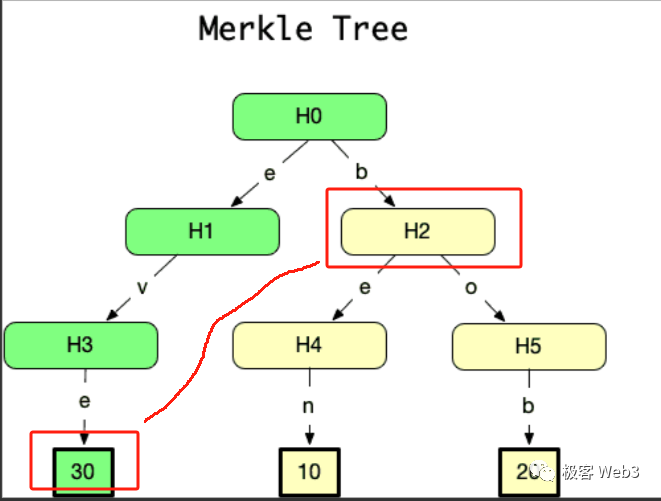

(The data block 30 and H2 in the diagram together form a Merkle Proof proving that data block 30 exists in the Merkle Tree corresponding to H0)

This succinctness of Merkle Proof is frequently used in Bitcoin, Ethereum, and cross-chain bridges. What we refer to as light nodes are essentially like Li Gang mentioned earlier—they receive only block headers from full nodes instead of complete blocks. It should be emphasized that Ethereum uses a Merkle Tree called the State Trie to summarize all accounts. Whenever any account state linked to the State Trie changes, the Merkle Root of the State Trie—called the StateRoot—also changes.

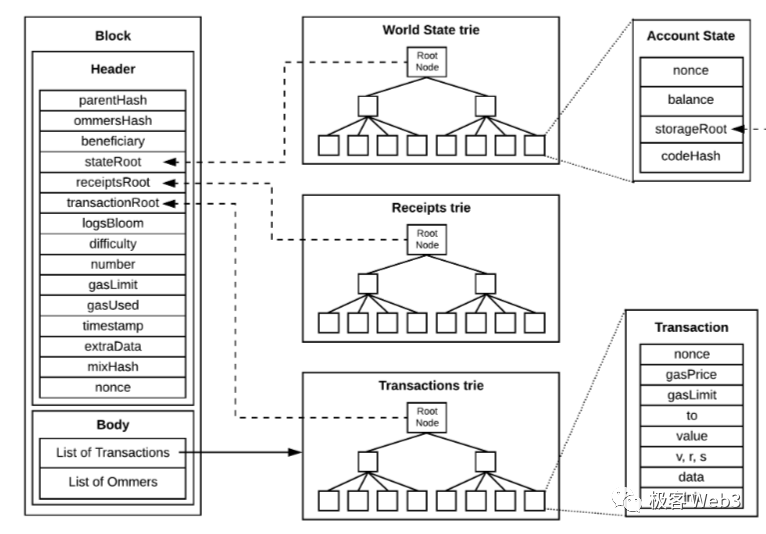

Ethereum block headers include the StateRoot, as well as the Merkle Root of the transaction tree (abbreviated as Txn Root). A key difference between the transaction tree and the state tree lies in the type of data represented by their leaf nodes. For instance, if block number 100 contains 300 transactions, then the leaves of the transaction tree represent those 300 transactions.

Another difference is that the State Trie contains a massive amount of data—its leaves correspond to all addresses on Ethereum (including many outdated state hashes). Thus, the full dataset of the State Trie is never published in blocks; only the StateRoot is recorded in the block header. In contrast, the raw dataset of the transaction tree consists of the transaction data within each block, and its TxnRoot is stored in the block header.

Since light nodes only receive block headers and thus only know the StateRoot and TxnRoot, they cannot reconstruct the full Merkle Tree from the Root alone (a consequence of the properties of Merkle Trees and hash functions). Therefore, light nodes cannot access the actual transaction data inside the block nor determine which accounts have changed state.

If Wang Qiang wants to prove to a certain light node (Li Gang mentioned earlier) that block number 100 contains a specific transaction—and assuming the light node already knows the header of block 100 and its TxnRoot—then the task becomes: prove that this transaction exists in the Merkle Tree corresponding to the TxnRoot. At this point, Wang Qiang simply needs to submit the corresponding Merkle Proof.

In many cross-chain bridges based on light client designs, the lightweight and succinct nature of light nodes and Merkle Proofs is commonly utilized. For example, ZK bridges like Map Protocol deploy a contract on the ETH chain specifically designed to receive block headers from other chains (e.g., Polygon). When a relayer submits the header of Polygon’s 100th block to the contract on the ETH chain, the contract verifies the header’s validity (e.g., whether it includes signatures from 2/3 of the POS validators in the Polygon network).

If the header is valid and a user claims to have initiated a cross-chain transaction from Polygon to ETH that was included in Polygon’s 100th block, they can simply use a Merkle Proof to demonstrate that their cross-chain transaction corresponds to the TxnRoot in the 100th block header (in other words, to prove that their cross-chain transaction was recorded in Polygon’s 100th block). However, ZK bridges further reduce verification costs by using zero-knowledge proofs to compress the computational overhead required to verify the Merkle Proof, thereby lowering the cost for the bridge contract.

DA and Data Withholding Attacks

After discussing Merkle Trees, Merkle Roots, and Merkle Proofs, we return to the DA and data withholding attack issue introduced at the beginning. This problem had already been discussed before 2017, and Celestia’s original paper traces the origins of the DA problem. Vitalik himself discussed in a document from 2017–2018 how block proposers might intentionally withhold certain data segments of a block and publish incomplete blocks. As a result, full nodes cannot verify the correctness of transaction execution or state transitions.

In such cases, block proposers could steal user assets—for example, transferring all coins from account A to another address—while full nodes cannot determine whether A authorized the transfer, since they lack access to the complete transaction data in the latest block.

On Layer1 public blockchains like Bitcoin or Ethereum, honest full nodes would directly reject such invalid blocks. But light nodes are different—they only receive block headers from the network, knowing only the StateRoot and TxnRoot, without access to the full underlying data corresponding to the header and roots.

In the Bitcoin whitepaper, there was speculation about such scenarios. Satoshi Nakamoto suggested that most users might prefer running low-resource light nodes, which cannot independently verify whether a block header corresponds to a valid block. If a block is invalid, honest full nodes would send alerts to light nodes.

However, Satoshi did not elaborate further on this idea. Later, Vitalik and Mustafa, founder of Celestia, built upon this concept and combined it with prior research to introduce DA data sampling—ensuring that honest full nodes can reconstruct the complete data of every block and raise alarms when necessary.

Plasma’s Fraud Proofs

Simply put, Plasma is a scaling solution that only posts Layer2 block headers to Layer1, while DA data outside the headers (complete transaction datasets / individual account state changes) are published off-chain. In other words, Plasma works similarly to a cross-chain bridge based on light clients—implementing a Layer2 light client via a contract on the ETH chain. When users wish to withdraw assets from L2 to L1, they must submit a Merkle Proof to prove ownership of those assets.

The validation logic for withdrawing assets from L2 to L1 resembles that of the previously mentioned ZK bridges, except Plasma relies on fraud proofs rather than ZK proofs—making it closer to what’s known as an “optimistic bridge.” Withdrawal requests from L2 to L1 in the Plasma network are not immediately processed but enter a “challenge period.” The purpose of this challenge period will be explained below.

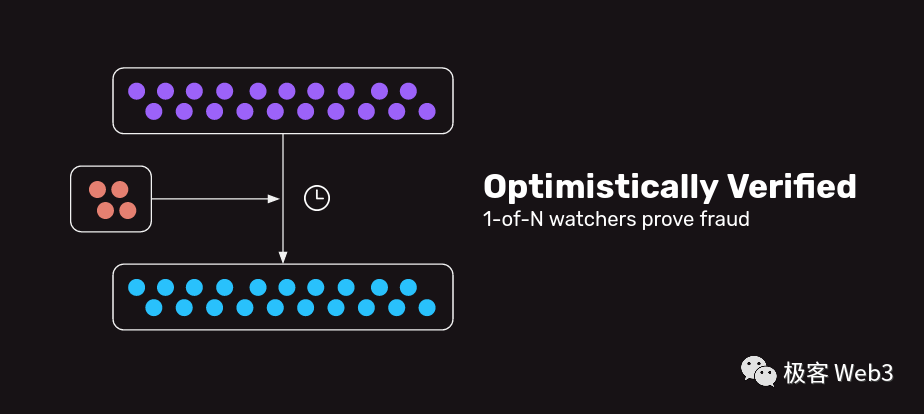

Plasma imposes no strict requirements on data publication/DA. The sequencer/operator broadcasts each L2 block off-chain, and interested nodes retrieve it voluntarily. Then, the sequencer posts the L2 block header to Layer1. For example, the sequencer first broadcasts block 100 off-chain, then publishes its header on-chain. If block 100 contains invalid transactions, any Plasma node can, before the challenge period ends, submit a Merkle Proof to the contract on ETH proving that the header of block 100 links to an invalid transaction. This is one scenario covered by fraud proofs.

Other applications of Plasma’s fraud proofs include:

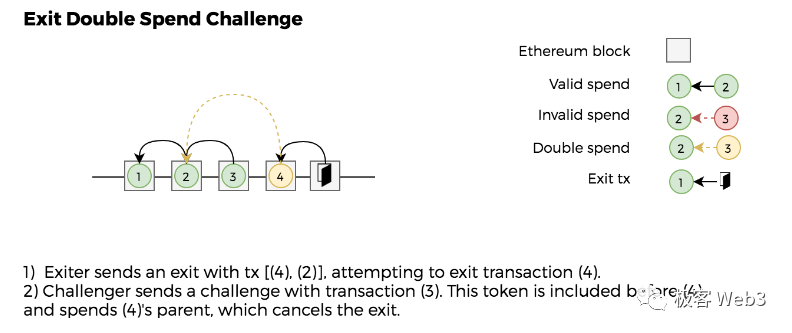

1. Suppose the Plasma network has progressed to block 200, and user A initiates a withdrawal claim stating they held 10 ETH at block 100. In reality, however, user A spent their ETH after block 100.

Thus, A is attempting to withdraw 10 ETH they previously possessed—even though they’ve already spent them. This is a classic case of “double spending.” In this case, anyone can submit a Merkle Proof showing A’s current asset status contradicts their withdrawal claim—i.e., proving A no longer holds the claimed funds after block 100 (different Plasma schemes vary in how they handle such proofs, with account-based models being far more complex than UTXO for double-spend detection).

2. In UTXO-based Plasma designs (which were dominant historically), block headers do not contain StateRoots—only TxnRoots (UTXO doesn’t support Ethereum-style account models or global state structures like State Trie). In other words, UTXO-based chains maintain transaction records but not state records.

In such cases, the sequencer itself might launch a double-spend attack—e.g., re-spending a UTXO that was already spent or minting new UTXOs out of thin air. Any user can submit a Merkle Proof demonstrating that the UTXO was previously used (spent) in earlier blocks or that its historical origin is invalid.

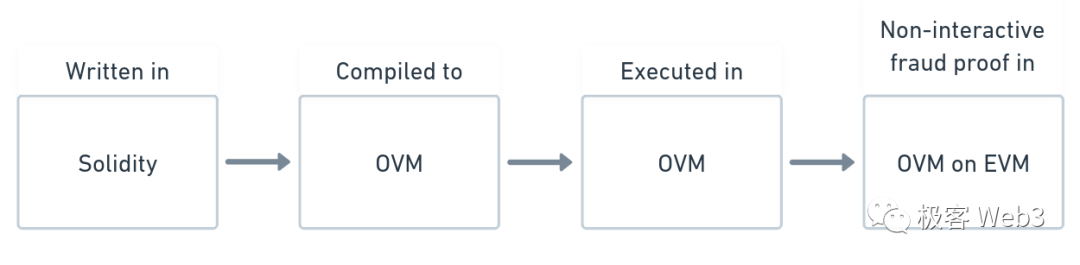

3. For EVM-compatible/State Trie-supporting Plasma designs, the sequencer might submit an invalid StateRoot. For example, after executing the transactions in block 100, the StateRoot should transition to ST+, but the sequencer submits ST- to Layer1.

Fraud proofs in such cases are more complex, requiring replaying all transactions in block 100 on Ethereum, consuming significant gas due to computation and input parameters. Early teams adopting Plasma struggled to implement such complex fraud proofs, so most opted for UTXO models, where fraud proofs are simpler and easier to implement (Fuel, the first Rollup scheme to launch fraud proofs, was based on UTXO).

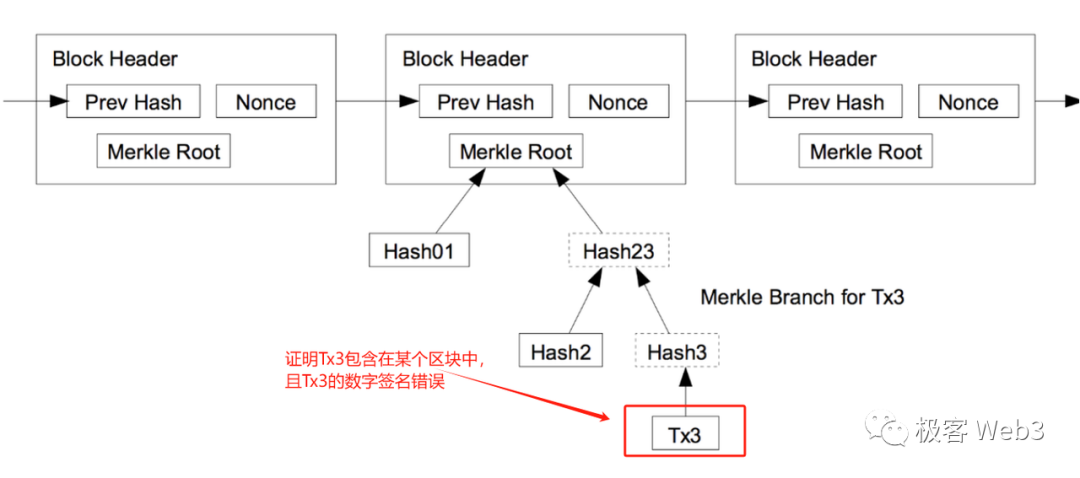

Data Withholding and Exit Game

Of course, the above fraud proofs only work under the assumption that DA/data publication is functioning properly. If the sequencer performs data withholding and fails to publish complete blocks off-chain, Plasma nodes cannot verify the validity of the block headers on Layer1, making it impossible to generate effective fraud proofs.

In such cases, the sequencer can steal user assets, for example, privately transferring all coins from account A to account B, then sending funds from B to C, and finally initiating a withdrawal in C’s name. Since B and C are controlled by the sequencer, the B→C transaction, even if publicly visible, causes no harm. But the sequencer can withhold the data of the invalid A→B transfer, preventing others from proving that B and C’s assets originate from fraudulent activity (proving B’s funds are tainted would require exposing a forged digital signature in the A→B transaction).

UTXO-based Plasma schemes have countermeasures—such as requiring users to submit the full history of their asset sources during withdrawals—with later improvements introduced over time. But EVM-compatible Plasma schemes struggle here. Validating withdrawal legitimacy involving contract-related transactions incurs enormous on-chain costs, making it hard to implement effective withdrawal verification in account-model-and-smart-contract-supporting Plasma systems.

Moreover, setting aside the above, regardless of whether UTXO-based or account-model-based, any data withholding incident in Plasma typically triggers widespread panic, as users cannot know which transactions the sequencer executed. Plasma nodes may sense something is wrong but cannot issue targeted fraud proofs because the required data was never released by the Plasma sequencer.

At this point, users only see the block headers without knowing their contents or the status of their assets. They collectively initiate withdrawal claims, attempting to withdraw using Merkle Proofs tied to historical blocks—triggering an extreme scenario known as the “Exit Game,” leading to a stampede that severely congests Layer1 and still results in asset losses for some users (those who don’t monitor alerts or social media may remain unaware that the sequencer is stealing funds).

Therefore, Plasma is an unreliable Layer2 scaling solution—once a data withholding attack occurs, it triggers the “Exit Game” and easily leads to user losses, a major reason for its abandonment.

Why Plasma Struggles to Support Smart Contracts

After discussing the Exit Game and data withholding, let’s examine why Plasma struggles to support smart contracts—mainly for two reasons:

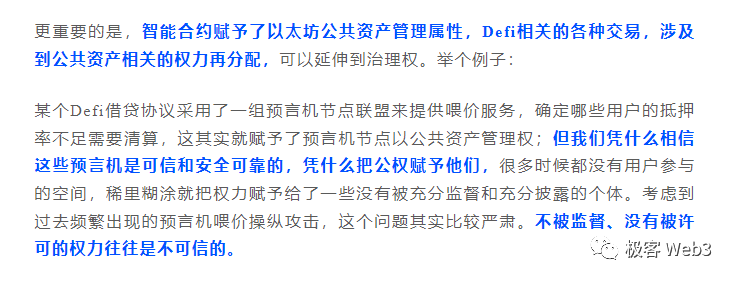

First, who should withdraw DeFi contract assets to Layer1? This essentially involves migrating contract state from Layer2 to Layer1. Suppose someone deposited 100 ETH into a DEX liquidity pool, and then the Plasma sequencer turns malicious, forcing emergency withdrawals. At this moment, the user’s 100 ETH remains under the control of the DEX contract. So, who should withdraw these funds to Layer1?

Ideally, users could first redeem their assets from the DEX and then withdraw them to L1 themselves. But the problem is the Plasma sequencer is already malicious and may arbitrarily reject user requests.

Alternatively, could we pre-assign an Owner to the DEX contract, allowing them to withdraw contract assets to L1 in emergencies? Clearly, this grants the Owner control over public assets—they could withdraw all funds and disappear. Isn’t that terrifying?

Clearly, determining how to handle these “public assets” controlled by DeFi contracts is a huge minefield. This touches on the difficulty of power distribution—a topic previously discussed by Xiangma in the interview “High-Performance Public Chains Struggle to Innovate: Smart Contracts Involve Power Distribution”.

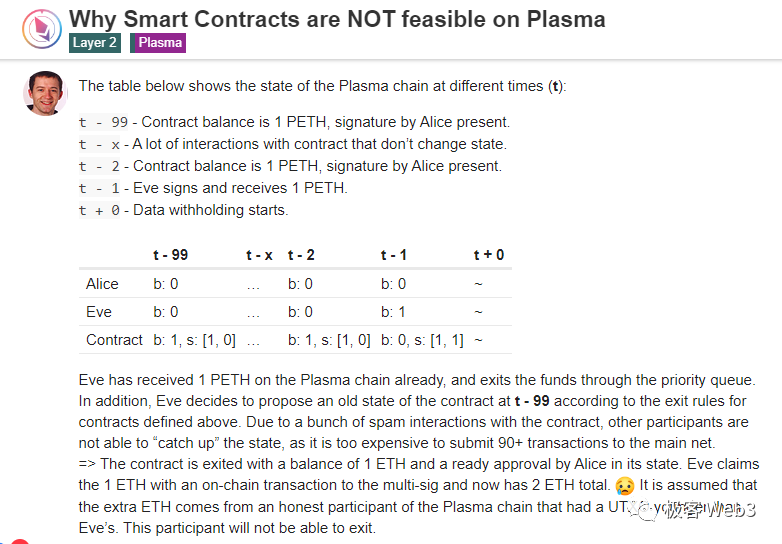

Second, disallowing contract state migration causes significant losses; but allowing contracts to migrate their state to Layer1 introduces double-spending issues that Plasma fraud proofs cannot resolve:

For example, suppose Plasma adopts Ethereum’s account model and supports smart contracts, and there’s a mixer contract currently holding 100 ETH, owned and controlled by Bob.

Suppose Bob withdraws 50 ETH from the mixer at block 100. Later, Bob initiates a withdrawal, moving these 50 ETH to Layer1.

Then, Bob uses an old snapshot of the contract state (e.g., from block 70) to migrate the mixer’s past state to Layer1, thereby transferring the mixer’s “former” 100 ETH to Layer1 as well.

Clearly, this is a classic case of “double withdrawal”—essentially double spending. Bob withdraws 150 ETH to Layer1, but users on the Layer2 network only contributed 100 ETH to the mixer/Bob—50 ETH are siphoned off out of nowhere. This could easily drain Plasma’s reserves. In theory, users could file a fraud proof showing the mixer contract state changed after block 70.

But if, after block 70, all transactions interacting with the mixer contract didn’t alter its state—except for Bob’s 50 ETH withdrawal—and you need to provide evidence of state change, you’d have to replay all those transactions on Ethereum to prove the state did change (this complexity stems from Plasma’s fundamental architecture). If the number of such transactions is huge, the fraud proof cannot be published on Layer1 (it would exceed Ethereum’s per-block gas limit).

Theoretically, in the above double-spend scenario, submitting the mixer’s current state snapshot (essentially the Merkle proof corresponding to the StateRoot) might seem sufficient. But since Plasma doesn’t publish transaction data on-chain, the contract cannot verify whether the submitted state snapshot is valid. The sequencer itself might perform data withholding, submitting an invalid state snapshot to falsely accuse any withdrawer.

For instance, when you claim you have 50 ETH and initiate a withdrawal, the sequencer might secretly zero your balance, perform data withholding, post an invalid StateRoot on-chain, and submit a falsified state snapshot accusing you of having no funds. At this point, no one can prove the sequencer’s StateRoot and state snapshot are invalid—because of data withholding, you lack sufficient data to construct a fraud proof.

To prevent this, when a Plasma node presents a state snapshot to prove someone double-spent, they must also replay all transaction records during that period—preventing the sequencer from blocking withdrawals via data withholding. In contrast, in Rollup, encountering such double withdrawals theoretically doesn’t require replaying history—because Rollup eliminates data withholding by “forcing” the sequencer to publish DA data on-chain. If a Rollup sequencer submits an invalid StateRoot/state snapshot, it either fails contract verification (ZK Rollup) or gets quickly challenged (OP Rollup).

Beyond the mixer example, multi-signature contracts and similar scenarios can also trigger double withdrawals in Plasma networks. Fraud proofs are highly inefficient in handling such cases. This situation has been analyzed in ETH Research.

In summary, due to Plasma’s incompatibility with smart contracts and lack of support for migrating contract states to Layer1, mainstream Plasma implementations resort to UTXO or similar mechanisms, as UTXO avoids ownership conflicts and supports compact, efficient fraud proofs. However, this limits use cases primarily to simple transfers or order-book exchanges.

Furthermore, since fraud proofs heavily depend on DA data, an unreliable DA layer undermines the efficiency of fraud proof systems. Plasma’s simplistic handling of DA fails to address data withholding attacks. With the rise of Rollup, Plasma has gradually faded into obscurity.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News