Blast to Layer2 Multisig Backdoor: Which Matters More, Technology or Social Consensus?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Blast to Layer2 Multisig Backdoor: Which Matters More, Technology or Social Consensus?

Web3's "rule by individuals" is fundamentally different from the "rule by individuals" in real-world sovereign states.

Author: Faust, GeekerWeb3

Introduction: The underlying message from Blast toward orthodox Layer2s like Polygon zkEVM might be, "Are kings and generals born of a different breed?" Since none of us are truly trustless—and security ultimately rests on social consensus—why criticize Blast for not being "Layer2 enough"? Isn't it excessive to turn against one's own?

Indeed, Blast has been widely criticized for relying on a 3-of-5 multisig to control its deposit address. Yet most Layer2s similarly rely on multisigs to manage their contracts; previously, Optimism even used just a single EOA address to control contract upgrades. In an environment where nearly all mainstream Layer2s carry similar multisig-related risks, criticizing Blast for lacking security feels more like tech elites looking down on a yield-chasing project.

But beyond comparing which approach is better or worse, the deeper purpose of blockchain lies in solving information opacity within social consensus and democratic governance. While championing technological superiority, we must acknowledge that social consensus itself is more fundamental—it underpins the effective operation of every Web3 project. In essence, technology serves social consensus; no matter how advanced a project’s technology, if it lacks broad recognition, it remains nothing more than an ornamental appendix.

Main text: Recently, Blast—a new project launched by Blur’s founder—has taken the internet by storm. Marketed as a Layer2, this “yield-generating” protocol operates via a deposit address deployed on the Ethereum chain. When users send funds to this address, those assets are used for native ETH staking, deposited into MakerDAO to earn interest, and other yield strategies, with profits returned to users.

Fueled by the founder’s reputation and an attractive incentive model, Blast secured $20 million in funding led by Paradigm and attracted massive retail participation. Within five days of launch, Blast’s deposit contract had accumulated over $400 million in TVL. Without exaggeration, Blast acted like a powerful stimulant in the midst of a long bear market, instantly igniting widespread excitement.

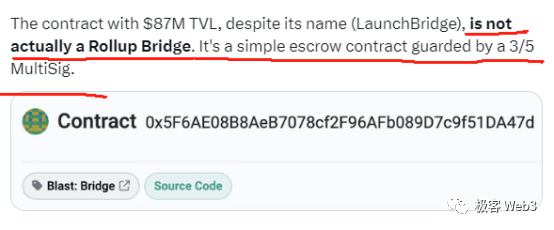

However, alongside its initial success, Blast has drawn sharp criticism from experts. For instance, engineers from L2BEAT and Polygon pointed out bluntly: current Blast merely deploys a deposit contract on Ethereum. This contract can be upgraded under the control of a 3-of-5 multisig, meaning its code logic could be rewritten—and yes, they could still pull a rug. Furthermore, while Blast claims it will eventually implement a rollup architecture, at present it’s just an empty shell, with withdrawal functionality not expected until February next year.

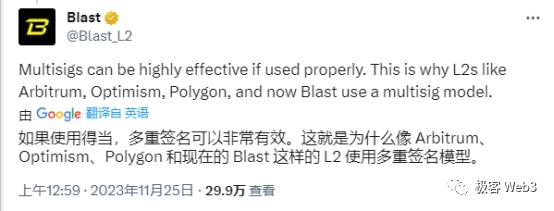

Blast fired back, noting that the vast majority of rollups also rely on multisigs to manage upgrade permissions—so accusations against Blast amount to fifty steps mocking a hundred.

Multisig in Layer2 is a long-standing issue

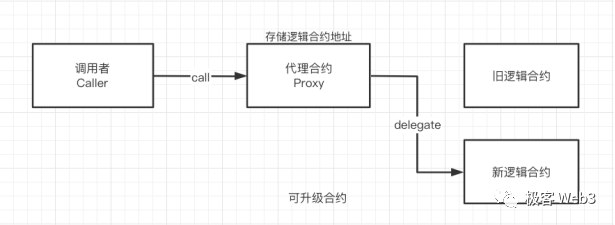

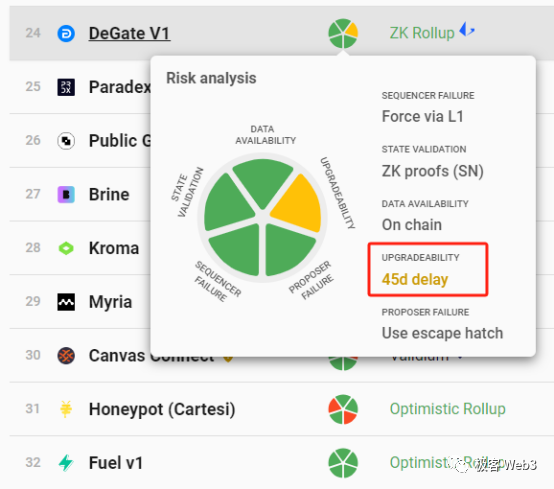

In fact, multisig governance in Layer2 contracts is nothing new. Back in July, L2BEAT conducted a dedicated study on upgradability in rollup contracts. “Upgradability” here refers to changing the logic contract address pointed to by a proxy contract, thereby altering its behavior. If the updated contract contains malicious logic, the Layer2 team could theoretically steal user assets.

(Image source: wtf academy)

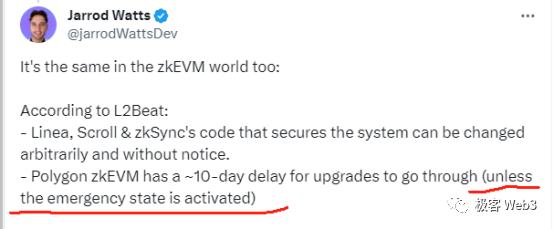

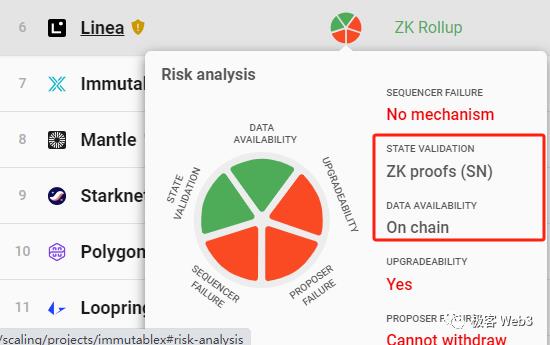

According to L2BEAT data, major rollups including Arbitrum, Optimism, Loopring, ZKSync Lite, zkSync Era, Starknet, and Polygon ZKEVM all use multisig-controlled upgradable contracts that can bypass timelocks and upgrade immediately. (See previous GeekerWeb3 article: The Game of Trust: Rollups Controlled by Multisigs and Committees)

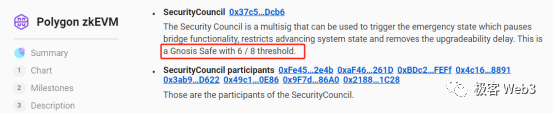

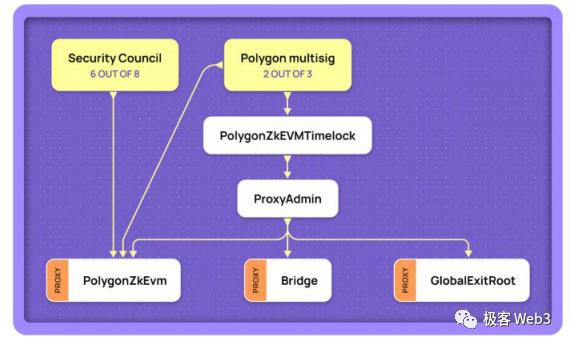

Surprisingly, Optimism previously relied solely on a single EOA address to manage contract upgrades—the multisig wasn’t added until October. As for Polygon zkEVM, which criticized Blast, it allows a so-called “emergency takeover” under 6-of-8 multisig authorization, shifting Layer2 governance from smart contract rules to outright human control. Interestingly, the same Polygon engineer who criticized Blast acknowledged this but remained vague about it.

What’s the rationale behind such “emergency modes”? Why do most rollups build in emergency buttons or backdoors? As Vitalik once explained, rollups need to frequently update their Ethereum-deployed contracts during development. Without proxy-based upgradability mechanisms, efficient iteration would be difficult.

Moreover, smart contracts holding large amounts of assets may contain subtle bugs, and development teams are prone to oversight. If hackers exploit these vulnerabilities, massive losses could occur. Hence, both Layer2s and DeFi protocols often include emergency switches, allowing “committee members” to intervene when necessary to prevent catastrophic events.

Of course, the committees set by Layer2s can often bypass timelock restrictions and upgrade contracts instantly, making them potentially more concerning than external threats like hackers. In other words, any smart contract managing significant assets inevitably involves some degree of “trust assumption”—namely, trusting that the multisig signers won’t act maliciously. Unless the contract is designed as immutable and free of critical bugs, complete trustlessness remains unattainable.

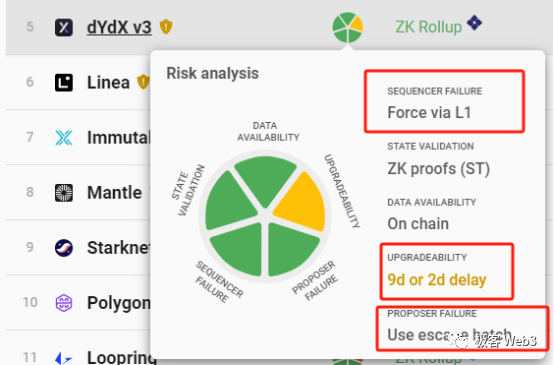

In practice, most mainstream Layer2s either allow designated committees to upgrade contracts immediately or impose relatively short timelocks (e.g., any dYdX contract upgrade requires at least a 48-hour delay). If users detect malicious logic in proposed contract updates, they theoretically have time to react by withdrawing assets back to Layer1.

(For more on forced withdrawals and escape hatches, see our previous article: How Important Are Forced Withdrawals and Escape Hatches for Layer2?)

(A timelock means certain operations are only allowed after a specified delay.)

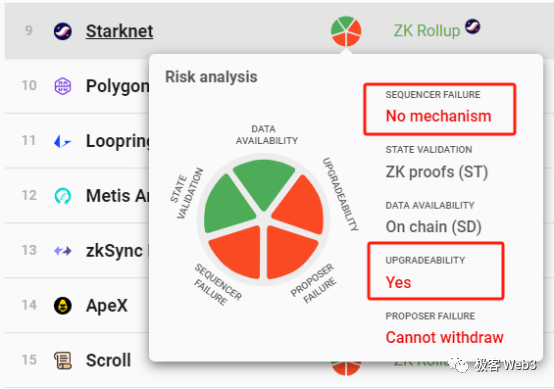

The real problem, however, is that many Layer2s don’t even offer forced withdrawal mechanisms that bypass the sequencer. In such cases, if the official team intends to act maliciously, they could first instruct the sequencer to reject all withdrawal requests, then transfer user assets to an L2 account controlled by the team. Afterward, they can upgrade the rollup contract at will, and once the timelock expires, withdraw all funds to Ethereum and abscond.

And in reality, the situation may be worse—most rollup teams can upgrade contracts without being bound by timelocks, meaning they could execute billion-dollar rugs almost instantaneously.

A truly trustless Layer2 should ensure contract upgrade delays exceed forced withdrawal delays

To solve the trust and security issues in Layer2, several conditions must be met:

Establish a censorship-resistant withdrawal exit on Layer1, allowing users to directly withdraw assets from Layer2 to Ethereum without needing sequencer approval. The delay for forced withdrawals should not be too long, ensuring users can quickly exit L2;

Any upgrade to the Layer2 contract must be subject to a timelock delay, with contract upgrades taking effect only after forced withdrawals become available. For example, if dYdX requires at least 48 hours for contract upgrades, the forced withdrawal or escape hatch mechanism should activate within less than 48 hours. This way, if users discover malicious code in a proposed contract update, they can withdraw assets to Layer1 before the upgrade goes live.

Currently, most rollups that have implemented forced withdrawal or escape hatch mechanisms fail to meet these criteria. For instance, dYdX’s forced withdrawal/escape mode has a maximum delay of seven days, while the committee’s contract upgrade delay is only 48 hours—meaning the committee could deploy a new contract before users’ forced withdrawals take effect, stealing assets before anyone escapes.

From this perspective, apart from Fuel, ZKSpace, and DeGate, no other rollup guarantees processing forced withdrawals before contract upgrades, implying high levels of trust assumptions across the board.

Many Validium-based projects (where data availability is handled off-chain) may have long contract upgrade delays (e.g., eight days or more), but Validium relies on off-chain DAC nodes to publish latest data, and DACs could launch data withholding attacks rendering forced withdrawals ineffective—thus failing to meet the above security model. (See our earlier article: Expelling Validium? Re-understanding Layer2 from the Perspective of Danksharding’s Creator)

At this point, we can clearly conclude: Every Layer2 solution except Fuel, ZKSpace, and DeGate is not trustless. Users must either trust the Layer2 team or its security council not to act maliciously, trust off-chain DAC nodes not to collude, or trust the sequencer won’t censor transactions (i.e., reject withdrawal requests). Only these three currently satisfy true security, censorship resistance, and trustlessness.

Security isn’t achieved through technology alone—it requires social consensus

This discussion isn’t new. The idea that Layer2s fundamentally depend on trust in their teams has long been recognized. Avalanche and Solana founders have previously criticized this heavily. But the truth is, these trust assumptions exist not only in Layer2s but also in Layer1s and indeed all blockchain projects.

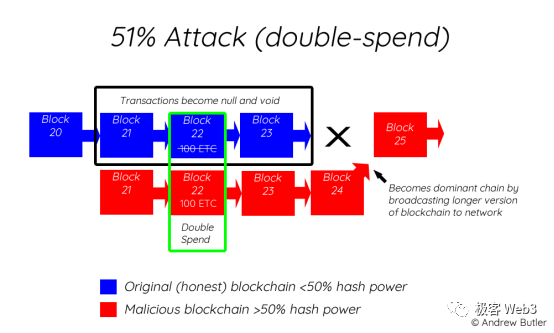

For example, we assume that validator nodes controlling two-thirds of stake weight on Solana won’t collude, and that Bitcoin’s top two mining pools won’t combine forces to launch a 51% attack and reorganize the longest chain. While such scenarios are unlikely, “unlikely” doesn’t mean “impossible.”

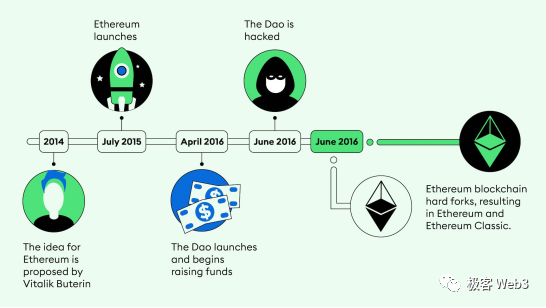

When traditional Layer1 blockchains suffer major malicious incidents causing widespread asset loss, resolution typically comes through social consensus: abandoning the compromised chain and forking a new one (as seen in the 2016 DAO incident splitting Ethereum into ETH and ETC). If someone attempts a malicious fork, communities again rely on social consensus to decide which fork to follow (e.g., most didn’t support the ETHW project).

Social consensus is the foundation ensuring orderly operation of blockchain projects and the DeFi protocols they host. Even technical safeguards like code audits and public disclosures of vulnerabilities are themselves components of social consensus. Purely technical decentralization often fails to deliver meaningful impact, remaining theoretical rather than practical.

What truly matters in critical moments is often non-technical: social consensus, public scrutiny beyond academic papers, and community acceptance independent of technological narratives.

Imagine this scenario: a little-known PoW chain currently appears highly decentralized because no single entity dominates. But suppose a mining company suddenly directs all its hash power to this chain, surpassing all other miners combined by many times. Instantly, decentralization collapses. If this miner acts maliciously, the only recourse left is social consensus.

Conversely, no matter how sophisticated a Layer2’s design, it cannot escape the necessity of social consensus. Even for Layer2s like Fuel, DeGate, and ZKSpace—where official malice is nearly impossible—their foundation, Ethereum Layer1, still heavily depends on social consensus, community governance, and public oversight.

Furthermore, our belief in immutability relies on statements from auditing firms and platforms like L2BEAT—but these entities could make mistakes or even lie. Though highly improbable, we must admit a minimal level of trust assumption still exists.

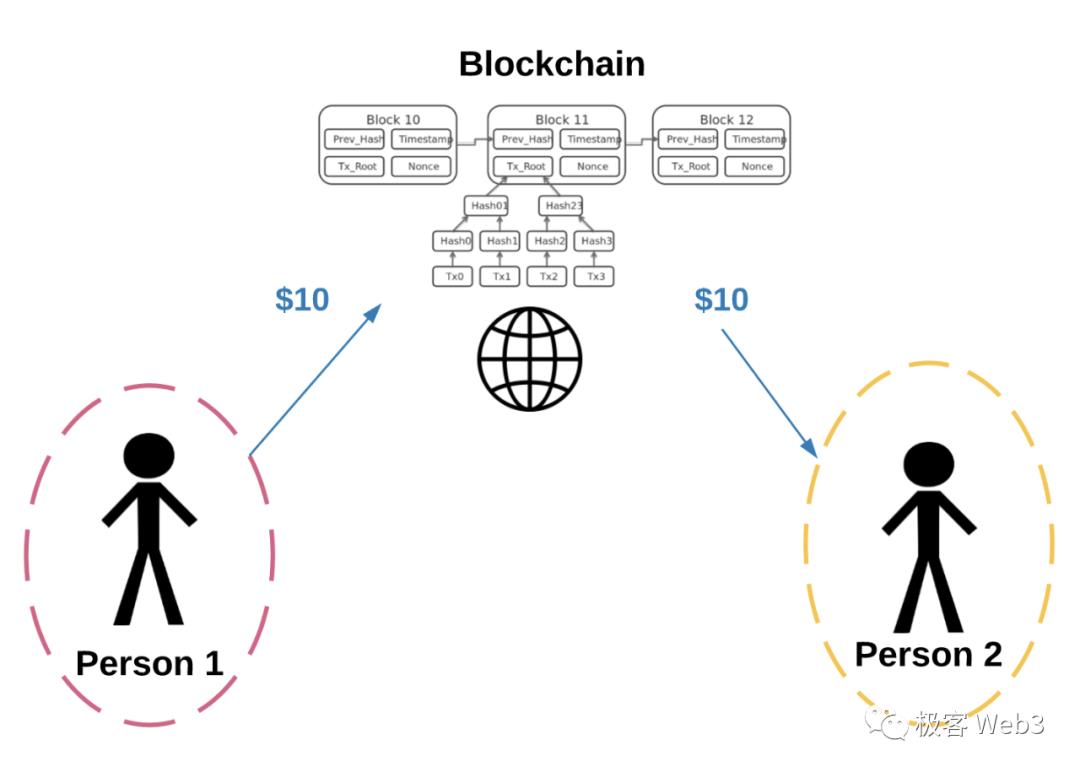

Yet, blockchain’s open-source nature allows anyone—including hackers—to inspect whether contracts contain malicious logic, minimizing trust assumptions and drastically reducing the cost of social consensus. When this cost drops low enough, we can reasonably consider it “trustless.”

Beyond the three mentioned above, other Layer2s lack genuine trustlessness. What truly ensures safety in emergencies remains social consensus. Technology often merely facilitates the process of social oversight. A project may boast superior technology but fail to gain broad recognition or attract a strong community, making decentralized governance and effective social consensus impossible.

Technology matters, but broader recognition and a thriving community culture are often more crucial, valuable, and conducive to sustainable growth.

Take zkRollups as an example: many currently only implement validity proofs and on-chain DA. They can prove that all processed transactions and transfers are valid—not fabricated by the sequencer—and thus haven’t cheated on “state transitions.” However, potential malicious behaviors by Layer2 operators or sequencers extend beyond this.

We can say that ZK proofs primarily reduce the cost of monitoring Layer2s, but many issues remain unsolvable by technology alone and require human intervention or social consensus.

If a Layer2 lacks censorship-resistant exits like forced withdrawals, or if the team attempts to upgrade contracts with logic to steal user funds, community members must rely on social consensus and public pressure to correct it. At that moment, technological superiority becomes secondary. Rather than debating whether technology ensures security, we should recognize that designing systems that enable effective social consensus is far more important—and this is the true essence of Layer2 and blockchain itself.

By observing Blast—which relies purely on social consensus for oversight—we should gain a clearer understanding of the relationship between social consensus and technical implementation, instead of judging projects solely based on how closely they align with Vitalik’s idealized vision of Layer2. Once a project gains recognition and attention from millions, social consensus has already formed. Whether driven by marketing or technological narrative matters less—the outcome outweighs the process.

Certainly, social consensus is an extension of democratic governance, and real-world experience has revealed flaws in democratic systems. However, blockchain’s inherent openness and data transparency dramatically reduce the cost of forming social consensus. Thus, Web3’s form of “human governance” differs fundamentally from that of sovereign states.

If we view blockchain as a tool to improve information transparency in democratic governance, rather than chasing the unattainable ideal of pure “code-enforced trustlessness,” the future appears much brighter and clearer. Only by shedding the arrogance and bias of tech elitism and embracing a broader audience can the Ethereum Layer2 ecosystem evolve into a globally adopted financial infrastructure.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News