Vitalik's Latest Technical Article: The Vision for the Ideal Wallet – A Comprehensive Upgrade from Cross-Chain Experience to Privacy Protection

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's Latest Technical Article: The Vision for the Ideal Wallet – A Comprehensive Upgrade from Cross-Chain Experience to Privacy Protection

A wallet is the window between users and the Ethereum world, and I believe focusing on security and privacy attributes is the most valuable.

Cross-L2 Transaction User Experience

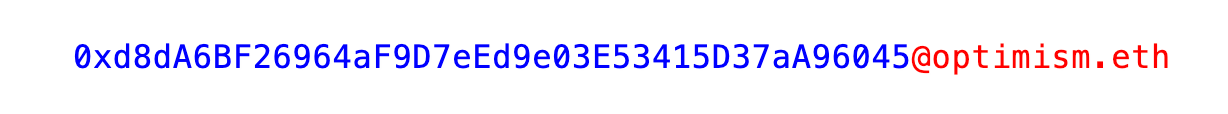

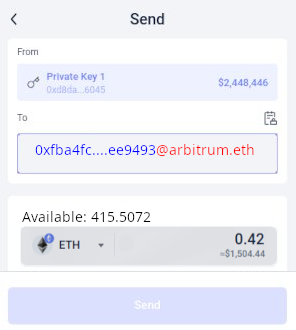

There is now an increasingly detailed roadmap for improving cross-L2 user experience, with both short-term and long-term components. Here, I will focus on the short-term part: ideas that could theoretically be implemented even today. The core idea is (i) built-in cross-L2 sending, and (ii) chain-specific addresses and payment requests. Your wallet should be able to provide you with an address (in the style of this ERC draft) like so: When someone (or some application) gives you an address in this format, you should be able to paste it into your wallet's "recipient" field and click “Send.” The wallet should automatically handle all necessary operations:

When someone (or some application) gives you an address in this format, you should be able to paste it into your wallet's "recipient" field and click “Send.” The wallet should automatically handle all necessary operations:

- If you already have sufficient tokens of the required type on the target chain, send directly

- If you hold the needed tokens on another chain (or multiple chains), use protocols such as ERC-7683 (essentially a cross-chain DEX) to transfer them

- If you hold different types of tokens on the same or other chains, use decentralized exchanges to convert them into the correct token type on the right chain and send. This requires explicit user approval: users must see exactly how much fee they pay and how much the recipient receives.

A possible model interface for wallets supporting cross-chain addresses

The above applies to the use case where “you copy-paste an address (or ENS, e.g., vitalik.eth@optimism.eth) so someone can pay you.” If a dapp requests a deposit (e.g., see this Polymarket example), the ideal flow would extend the web3 API to allow dapps to issue chain-specific payment requests. Your wallet could then fulfill that request in any needed way. For good UX, standardization of getAvailableBalance requests is also needed, and wallets need to carefully consider which chains should default-store user assets for maximum security and ease of transfers.

Chain-specific payment requests can also be encoded into QR codes scanned by mobile wallets. In face-to-face (or online) consumer payments, the receiver issues a QR code or web3 API call saying “I want X units of token Y on chain Z, with reference ID or callback W,” and the wallet is free to satisfy this request however it chooses. Another option is a claim link protocol, where the user’s wallet generates a QR code or URL containing authorization to claim a certain amount from their on-chain contract, leaving it to the receiver to figure out how to move those funds into their own wallet.

Another related topic is gas payment. If you receive assets on an L2 without ETH and need to make transactions there, the wallet should automatically use protocols (e.g., RIP-7755) to pay gas on a chain where you do hold ETH. If the wallet anticipates more future L2 transactions, it should also use a DEX to send, say, a few million worth of gas in ETH, so subsequent transactions can spend gas directly there (which is cheaper).

A possible model interface for wallets supporting cross-chain addresses

The above applies to the use case where “you copy-paste an address (or ENS, e.g., vitalik.eth@optimism.eth) so someone can pay you.” If a dapp requests a deposit (e.g., see this Polymarket example), the ideal flow would extend the web3 API to allow dapps to issue chain-specific payment requests. Your wallet could then fulfill that request in any needed way. For good UX, standardization of getAvailableBalance requests is also needed, and wallets need to carefully consider which chains should default-store user assets for maximum security and ease of transfers.

Chain-specific payment requests can also be encoded into QR codes scanned by mobile wallets. In face-to-face (or online) consumer payments, the receiver issues a QR code or web3 API call saying “I want X units of token Y on chain Z, with reference ID or callback W,” and the wallet is free to satisfy this request however it chooses. Another option is a claim link protocol, where the user’s wallet generates a QR code or URL containing authorization to claim a certain amount from their on-chain contract, leaving it to the receiver to figure out how to move those funds into their own wallet.

Another related topic is gas payment. If you receive assets on an L2 without ETH and need to make transactions there, the wallet should automatically use protocols (e.g., RIP-7755) to pay gas on a chain where you do hold ETH. If the wallet anticipates more future L2 transactions, it should also use a DEX to send, say, a few million worth of gas in ETH, so subsequent transactions can spend gas directly there (which is cheaper).

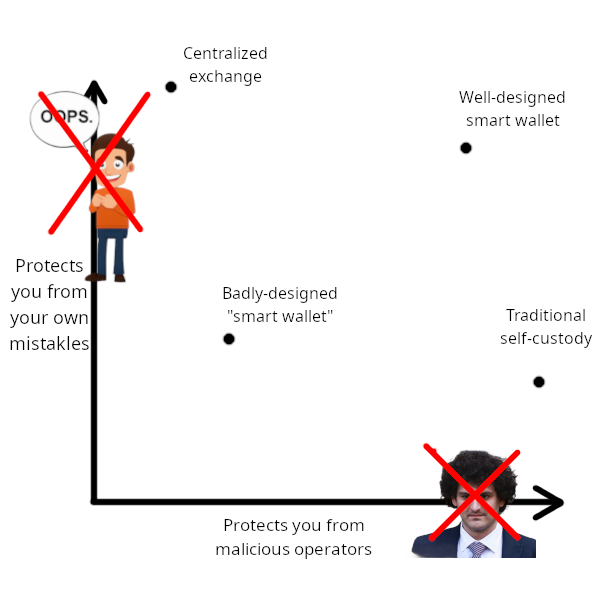

Account Security

One way I conceptualize account security challenges is that a good wallet should function well in two aspects: (i) protecting users from hackers or malicious actions by wallet developers, and (ii) protecting users from their own mistakes. The “mistake” on the left is unintentional. But when I saw it, I realized it fit perfectly in context, so I decided to keep it.

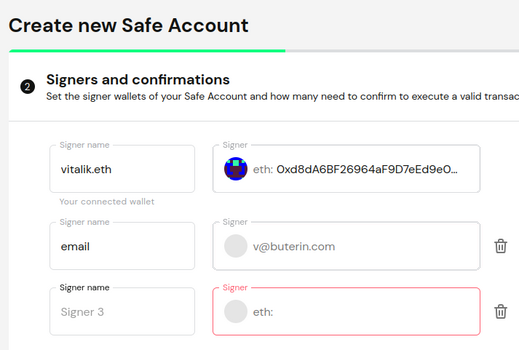

My preferred solution—advocated for overa decade—has been social recovery and multi-signature wallets with tiered access control. A user’s account has two layers of keys: a primary key and N guardians (e.g., N = 5). The primary key handles low-value and non-financial operations. Most guardians are required for (i) high-value operations, such as sending the full balance, or (ii) changing the primary key or any guardian. Optionally, the primary key could execute high-value operations via time lock.

This is the basic design, which can be extended. Session keys and permissioning mechanisms like ERC-7715 can help balance convenience and security across different applications. More complex guardian architectures—such as multiple time-lock durations at different thresholds—can maximize chances of successful legitimate recovery while minimizing theft risk.

The “mistake” on the left is unintentional. But when I saw it, I realized it fit perfectly in context, so I decided to keep it.

My preferred solution—advocated for overa decade—has been social recovery and multi-signature wallets with tiered access control. A user’s account has two layers of keys: a primary key and N guardians (e.g., N = 5). The primary key handles low-value and non-financial operations. Most guardians are required for (i) high-value operations, such as sending the full balance, or (ii) changing the primary key or any guardian. Optionally, the primary key could execute high-value operations via time lock.

This is the basic design, which can be extended. Session keys and permissioning mechanisms like ERC-7715 can help balance convenience and security across different applications. More complex guardian architectures—such as multiple time-lock durations at different thresholds—can maximize chances of successful legitimate recovery while minimizing theft risk.

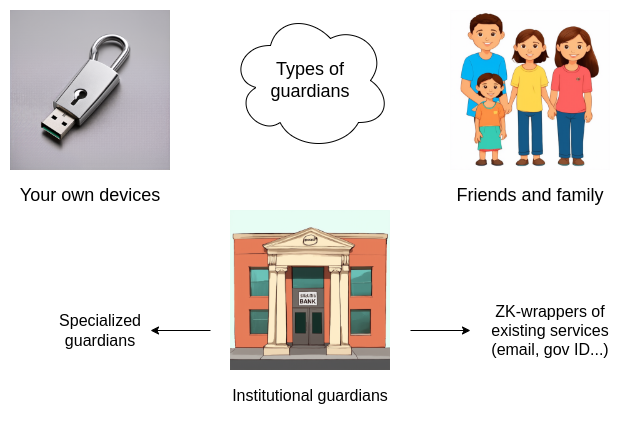

Who or What Should Guardians Be?

For experienced crypto users within a community of experienced users, a viable option is keys held by friends and family. If you ask each person to give you a new address, no one needs to know who they are—and your guardians don’t even need to know each other. Without collusion signals, coordinated betrayal is unlikely. However, this option isn’t available to most new users. A second option is institutional guardians: companies offering services that sign transactions only upon receiving additional confirmation from you—e.g., a verification code, or video call for high-value users. People have long tried building these—I introduced CryptoCorp back in 2013. Yet, so far, such companies haven’t succeeded much. A third option is multiple personal devices (e.g., phone, desktop, hardware wallet). This works but is hard to set up and manage for inexperienced users. There’s also risk of losing or having all devices stolen simultaneously, especially if stored together. Recently, we’re seeing more solutions based on passkeys. These can be backed up only on your device (making it a personal device solution) or in the cloud (relying on complexhybrid assumptions involving password security, institutions, and trusted hardware). In practice, passkeys offer meaningful security gains for average users, but alone aren’t enough to protect life savings. Fortunately, with ZK-SNARKs, we now have a fourth option: ZK-wrapped centralized IDs. Examples include zk-email, Anon Aadhaar, Myna Wallet, etc. Essentially, you take various forms of centralized ID (corporate or government) and convert them into Ethereum addresses, allowing transaction signing only via generating a ZK-SNARK proving ownership of that ID. With this addition, we now have broad options, and ZK-wrapped centralized IDs uniquely stand out for being beginner-friendly.

Implementation requires simple, integrated UI: you should be able to just specify “example@gmail.com” as a guardian, and the wallet auto-generates the corresponding zk-email Ethereum address under the hood. Advanced users should be able to input their email (and possibly a privacy salt stored with it) into an open-source third-party app and verify the generated address is correct. The same should apply to any other supported guardian type.

With this addition, we now have broad options, and ZK-wrapped centralized IDs uniquely stand out for being beginner-friendly.

Implementation requires simple, integrated UI: you should be able to just specify “example@gmail.com” as a guardian, and the wallet auto-generates the corresponding zk-email Ethereum address under the hood. Advanced users should be able to input their email (and possibly a privacy salt stored with it) into an open-source third-party app and verify the generated address is correct. The same should apply to any other supported guardian type.

Note that a current practical challenge for zk-email is its reliance on DKIM signatures, whose keys rotate every few months and aren't themselves signed by any authority. This means today’s zk-email carries trust assumptions beyond the provider; using TLSNotary inside trusted hardware to verify updated keys could reduce this, but it's suboptimal. Ideally, email providers would start directly signing their DKIM keys. Today, I recommend using zk-email as one guardian, but not most: avoid setups where fund access depends entirely on zk-email integrity.

Note that a current practical challenge for zk-email is its reliance on DKIM signatures, whose keys rotate every few months and aren't themselves signed by any authority. This means today’s zk-email carries trust assumptions beyond the provider; using TLSNotary inside trusted hardware to verify updated keys could reduce this, but it's suboptimal. Ideally, email providers would start directly signing their DKIM keys. Today, I recommend using zk-email as one guardian, but not most: avoid setups where fund access depends entirely on zk-email integrity.

New Users and In-App Wallets

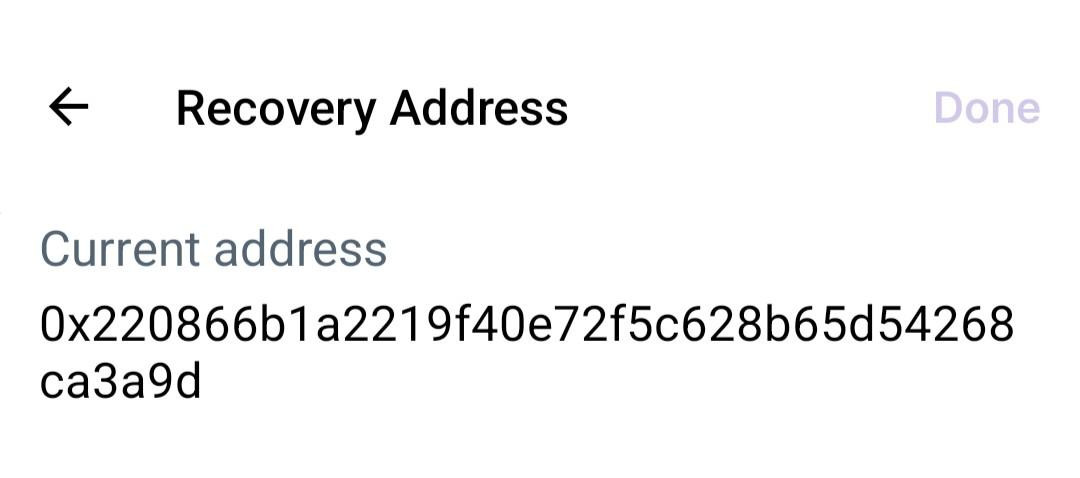

New users don’t actually want to enter many guardians during initial signup. So wallets should offer a very simple alternative. A natural path is a 2-of-3 setup using zk-email on their email address, a key locally stored on the user’s device (possibly a passkey), and a backup key held by the provider. As users gain experience or accumulate more assets, they should eventually be prompted to add more guardians. Wallet integration into apps is inevitable, since non-crypto-native apps don’t want users downloading two separate apps (the app itself plus an Ethereum wallet), creating friction. However, users of many app wallets should be able to link all their wallets together, so they only deal with one “access control problem.” The simplest method is a hierarchical scheme, where a fast “linking” process lets users designate their main wallet as the guardian for all in-app wallets. Farcaster client Warpcast already supports this: By default, recovery of your Warpcast account is controlled by the Warpcast team. But you can “take over” your Farcaster account and change recovery to your own address.

By default, recovery of your Warpcast account is controlled by the Warpcast team. But you can “take over” your Farcaster account and change recovery to your own address.

Protecting Users from Scams and Other External Threats

Beyond account security, today’s wallets do a lot to detect fake addresses, phishing, scams, and other external threats, striving to protect users. Yet, many countermeasures remain primitive—e.g., requiring clicks to send ETH or other tokens to any new address, whether $100 or $100,000. There’s no silver bullet here. It’s a series of gradual, ongoing fixes across threat categories. Still, continued improvement offers great value.Privacy

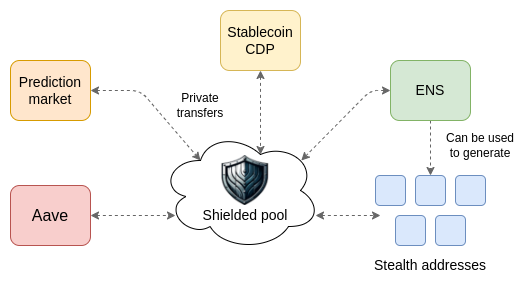

It’s time to take privacy on Ethereum more seriously. ZK-SNARK technology is now highly advanced, privacy-preserving techniques that don’t rely on backdoors to mitigate regulatory risks (like privacy pools) are maturing, and secondary infrastructure like Waku and ERC-4337 mempools is becoming more stable. However, private transfers on Ethereum still require users to explicitly download and use “privacy wallets” like Railway (or Umbra for stealth addresses). This creates major inconvenience and reduces the number of people willing to transact privately. The solution is private transfers must be directly integrated into wallets. A simple implementation follows: wallets can store part of a user’s assets as “private balance” in a privacy pool. When making a transfer, funds are first withdrawn automatically from the pool. To receive funds, the wallet can auto-generate a stealth address. Additionally, the wallet can automatically generate a new address for each application the user interacts with (e.g., DeFi protocols). Deposits come from the privacy pool, withdrawals go directly back in. This allows unlinking activity in one app from activity in others. An advantage of this approach is that it naturally supports not just private asset transfers, but also private identities. Identity already exists on-chain: any proof-of-personhood gated app (e.g., Gitcoin Grants), token-gated chat, Ethereum Follow Protocol, etc., constitutes on-chain identity. We want this ecosystem to be privacy-preserving too. That means a user’s on-chain activities shouldn’t be aggregated in one place: each project stores data separately, and the user’s wallet should be the only thing with a “global view” capable of seeing all proofs together. Native ecosystems with multiple accounts per user help achieve this, as do off-chain attestation protocols like EAS and Zupass.

This represents a pragmatic mid-term vision for Ethereum privacy. While some L1 and L2 features could make private transfers more efficient and reliable, this is implementable now. Some privacy advocates argue only fully private everything—encrypting the entire EVM—is acceptable. I think that may be the ideal long-term outcome, but it requires more fundamental rethinking of programming models and isn’t mature enough yet for deployment on Ethereum. We do need default privacy to achieve sufficiently large anonymity sets. But focusing first on (i) transfers between accounts and (ii) identity and identity-related use cases (like private attestations) is a pragmatic first step—easier to implement, and something wallets can start using now.

An advantage of this approach is that it naturally supports not just private asset transfers, but also private identities. Identity already exists on-chain: any proof-of-personhood gated app (e.g., Gitcoin Grants), token-gated chat, Ethereum Follow Protocol, etc., constitutes on-chain identity. We want this ecosystem to be privacy-preserving too. That means a user’s on-chain activities shouldn’t be aggregated in one place: each project stores data separately, and the user’s wallet should be the only thing with a “global view” capable of seeing all proofs together. Native ecosystems with multiple accounts per user help achieve this, as do off-chain attestation protocols like EAS and Zupass.

This represents a pragmatic mid-term vision for Ethereum privacy. While some L1 and L2 features could make private transfers more efficient and reliable, this is implementable now. Some privacy advocates argue only fully private everything—encrypting the entire EVM—is acceptable. I think that may be the ideal long-term outcome, but it requires more fundamental rethinking of programming models and isn’t mature enough yet for deployment on Ethereum. We do need default privacy to achieve sufficiently large anonymity sets. But focusing first on (i) transfers between accounts and (ii) identity and identity-related use cases (like private attestations) is a pragmatic first step—easier to implement, and something wallets can start using now.

Ethereum Wallets Must Also Be Data Wallets

A consequence of any effective privacy solution—whether for payments, identity, or other uses—is increased demand for users to store off-chain data. This was evident in Tornado Cash, which required users to keep every “ticket” representing a 0.1–100 ETH deposit. Modern privacy protocols sometimes store encrypted data on-chain, decryptable with a single private key. This is risky—if the key leaks or quantum computers become feasible, all data becomes public. The need for off-chain data storage is even clearer with off-chain attestation protocols like EAS and Zupass. Wallets must become not just software storing on-chain access rights, but also software storing your private data. The non-crypto world increasingly recognizes this too—e.g., see Tim Berners-Lee’s recent work on personal data storage. All the problems we solve around robust access control guarantees, we must also solve around robust data availability and non-leakage guarantees. Perhaps these solutions can overlap: if you have N guardians, use M-of-N secret sharing across them to store your data. Data is inherently harder to protect because you can’t revoke someone’s data share—but we should develop the safest possible decentralized custody solutions.Secure Chain Access

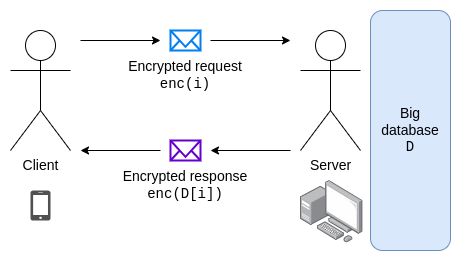

Today, wallets trust their RPC providers to tell them anything about the chain. This is a vulnerability with two aspects:- RPC providers might try to steal money by giving false information, e.g., about market prices.

- RPC providers can extract private information about which apps and other accounts the user is interacting with.

To ensure server honesty, individual database entries are Merkle branches, verifiable by clients via light clients.

PIR is computationally intensive. Several approaches exist to address this:

To ensure server honesty, individual database entries are Merkle branches, verifiable by clients via light clients.

PIR is computationally intensive. Several approaches exist to address this:

- Brute force: algorithmic or hardware improvements may make PIR fast enough. These may rely on preprocessing: servers store encrypted and shuffled data per client, enabling faster queries. The main challenge in Ethereum is adapting this to rapidly changing datasets (like state), reducing real-time cost but likely increasing total compute and storage overhead.

- Weaken privacy requirements: e.g., each lookup only has 1 million “mixins,” so the server knows the client accessed one of a million possible values, but no finer detail.

- Multi-server PIR: using multiple servers with 1-of-N honesty assumptions typically speeds up PIR algorithms.

- Anonymity instead of confidentiality: requests could be sent through mix networks to hide the sender rather than content. But doing this effectively increases latency, worsening UX.

Ideal Keystore Wallet

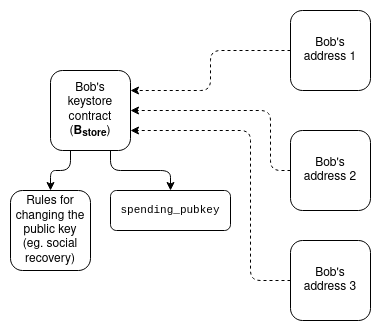

Beyond transfers and state access, another critical workflow needing smooth cross-L2 operation is changing an account’s validation configuration—either updating keys (e.g., recovery) or deeper changes to account logic. Three solution layers exist, ordered by increasing difficulty:- Replay updates: when a user changes configuration, the message authorizing this change is replayed on every chain where the wallet detects user assets. Ideally, message format and validation rules are chain-independent, enabling automatic replay across as many chains as possible.

- Keystore on L1: configuration data resides on L1; L2 wallets read it via L1SLOAD or remote static calls. Thus, config updates only needed on L1 propagate automatically.

- Keystore on L2: config data lives on L2; L2 wallets read it via ZK-SNARK. Same as (2), except keystore updates may be cheaper, but reads more expensive.

Solution (3) is particularly powerful because it integrates well with privacy. In normal “privacy solutions,” users hold a secret

Solution (3) is particularly powerful because it integrates well with privacy. In normal “privacy solutions,” users hold a secret s, publish a “leaf value” L on-chain, and prove L = hash(s, 1) and N = hash(s, 2) for some never-disclosed secret. A nullifier N is published to prevent future spending from the same leaf without revealing L, relying on user-held s security. A recovery-friendly privacy solution would say: s is an on-chain location (e.g., address and storage slot); users must prove a state query: L = hash(sload(s), 1).

Dapp Security

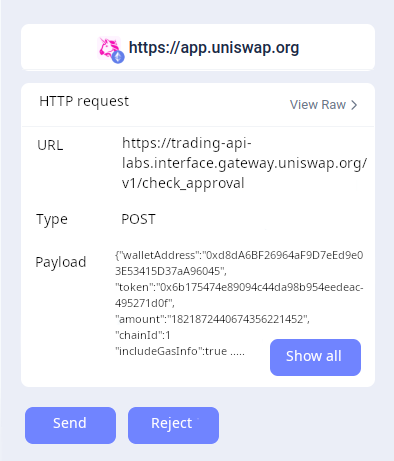

The weakest link in user security is usually dapps. Most users interact with apps via websites that implicitly download UI code in real-time from servers and execute it in-browser. If the server or DNS is compromised, users get a fake UI that may trick them into arbitrary actions. Wallet features like transaction simulation help reduce risk but are far from perfect. Ideally, we’d shift the ecosystem toward on-chain content versioning: users access dapps via ENS names containing IPFS hashes of interfaces. Updating the interface requires an on-chain transaction from a multisig or DAO. Wallets show users whether they’re interacting with a more secure on-chain interface or a less secure Web2 one. Wallets could also indicate whether they’re on a secure chain (e.g., stage 1+, multiple security audits). For privacy-conscious users, wallets could add a paranoid mode requiring user approval for HTTP requests, not just web3 operations: Possible interface model for paranoid mode

More advanced approaches go beyond HTML + JavaScript, writing dapp business logic in dedicated languages—possibly thin wrappers over Solidity or Vyper—so browsers can auto-generate UIs for any needed function. OKContract already does this.

Another direction is cryptoeconomic information defense: dapp developers, security firms, deployers, and others post bonds that pay affected users (as determined by an on-chain dispute-resolution DAO) if the dapp is hacked or severely misleads users. Wallets could display scores based on bond size.

Possible interface model for paranoid mode

More advanced approaches go beyond HTML + JavaScript, writing dapp business logic in dedicated languages—possibly thin wrappers over Solidity or Vyper—so browsers can auto-generate UIs for any needed function. OKContract already does this.

Another direction is cryptoeconomic information defense: dapp developers, security firms, deployers, and others post bonds that pay affected users (as determined by an on-chain dispute-resolution DAO) if the dapp is hacked or severely misleads users. Wallets could display scores based on bond size.

The Longer-Term Future

All of the above assumes traditional interfaces involving pointing, clicking, and typing. Yet, we’re also approaching deeper paradigm shifts:- Artificial intelligence, potentially shifting us from click-and-type to “say what you want, and bots figure it out”

- Brain-computer interfaces, including “mild” methods like eye-tracking and more direct or invasive technologies (see: Neuralink’s first patient this year)

- Client-side active defense: Brave browser actively protects users from ads, trackers, and other harmful elements. Many browsers, plugins, and crypto wallets have teams actively working to shield users from security and privacy threats. These “active guardians” will only grow stronger over the next decade.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News