Doubts and Reflections on Investing in the Blockchain Industry: Value or Speculation?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Doubts and Reflections on Investing in the Blockchain Industry: Value or Speculation?

Why do some people believe VC firms' investments are disconnected from the "market"?

By CaptainZ

I. The Dilemma of Investment

When I first entered the space, I often felt confused:

-

Is investing in blockchain projects value investing or pure speculation?

-

If it's value investing, why do many obvious scams generate strong profits?

-

If it's pure speculation, is industry research still useful?

-

How do you assess a project’s value in early-stage (primary market) investing?

-

Why do scam investments sometimes yield higher returns than so-called "value investments"?

-

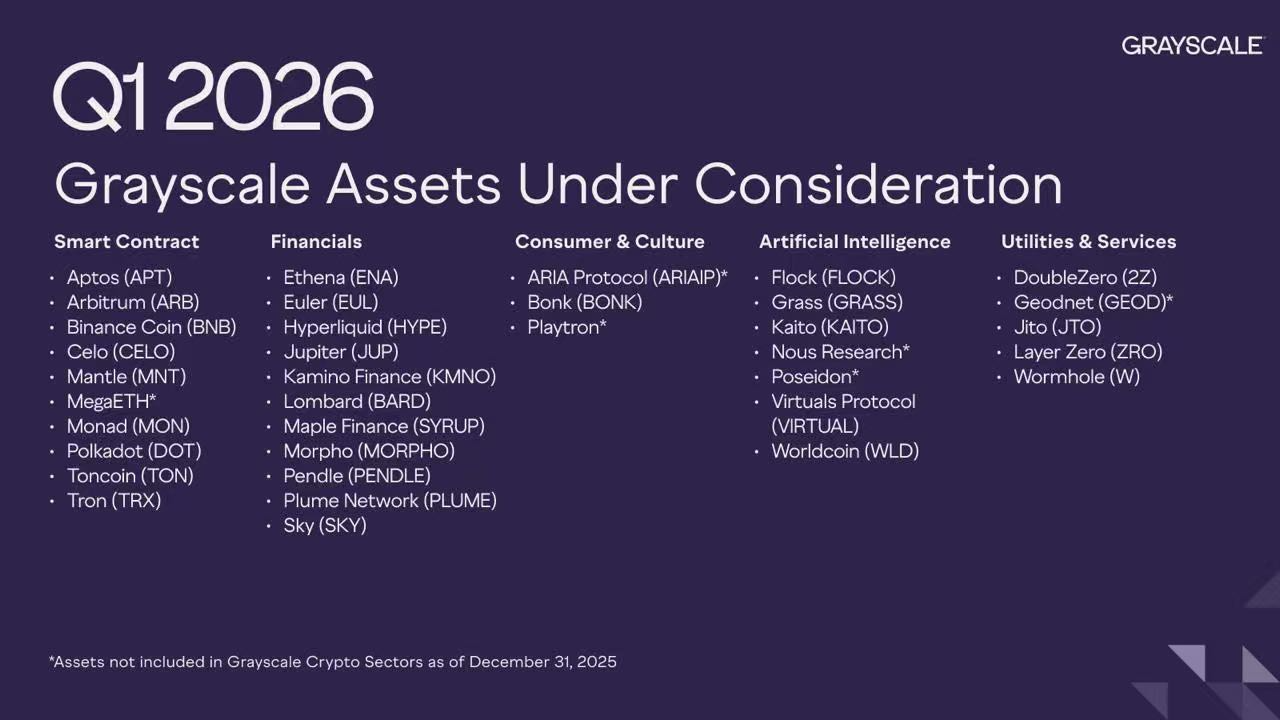

Why do some believe VC investments are disconnected from the "market"?

II. Origins of the Stock Market

Answering these questions isn't particularly easy. But before we begin, let's look at the history of traditional investment markets—the stock market.

Originally, entrepreneurship took the form of unlimited liability partnerships. With the emergence of capitalism, large-scale industrial ventures began to appear. To encourage investment and innovation, a new organizational structure was needed—one that limited investors’ liability. Thus, the joint-stock company was born: ownership of a company was divided into transferable shares, and shareholders' liability was limited to the value of their shares.

At the same time, entrepreneurs and investors found their stakes locked within business entities. To enable effective exits and entry for new shareholders, there arose an urgent need for an open market to trade company equities—leading to the birth of stock exchanges. For example, the London Stock Exchange founded in 1698. As capitalism and globalization advanced, stock markets gradually expanded worldwide, becoming the primary venue for corporate fundraising and investor participation.

III. Evolution of Valuation Methods

This brought about another question: how should company stocks be valued?

The earliest method was the "payback period" valuation—how long it would take to recoup your investment. Suppose a stable business generates 100 million in net profit annually. If all profits were distributed to shareholders, then investing 500 million for shares would mean recovering costs in approximately five years. This approach later became standardized as dividing the stock price by annual earnings.

Thus, the "payback period" evolved into the Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio, giving rise to two key valuation metrics: the P/E multiple and EPS (Earnings Per Share).

In essence, the P/E valuation method is simply a rough estimate of the payback period. Now, Bitcoin miners—does this sound familiar? Yes, the most common valuation method used today by miners when purchasing mining rigs is precisely the "payback period," which corresponds directly to the stock market’s "P/E ratio."

The payback period or P/E valuation is a "static valuation method"—it fails to account for future changes. As financial theory evolved, more finance professionals recognized the time value of money. For instance, in the same industry, Company A earns 100 million this year with projected earnings of 200 million next year and 300 million the following year, while Company B also earns 100 million this year but expects only 100 million next year and 50 million the year after. How should their valuations differ?

Expectations represent probabilistic forecasts of the future, requiring a valuation model that reflects both expectation and risk—thus emerged the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model. We won’t dive deep into the mathematical formulas here; just understand that DCF essentially calculates today’s value based on expected future earnings, adjusted for the "risk-free rate" and "risk premium."

Hence, P/E and DCF became the two most important valuation methods in capital markets.

IV. Efficient Markets and Behavioral Finance

However, valuation is never that simple. Can a few formulas really tell us which stock is undervalued or overvalued? The valuation methods mentioned above are highly objective benchmarks but ignore subjective human factors.

This brings us to behavioral finance.

Behavioral finance is an interdisciplinary field combining finance, psychology, behavior, and sociology, aiming to uncover irrational behaviors and decision-making patterns in financial markets. It argues that securities prices are not determined solely by intrinsic value, but significantly influenced by investor behavior—meaning psychological and behavioral factors play a major role in price formation and fluctuations. It stands in contrast to the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), primarily consisting of two components: limits to arbitrage and psychological biases.

In the 1950s, Von Neumann and Morgenstern established a framework for analyzing rational choice under uncertainty through axiomatic assumptions—the Expected Utility Theory. Arrow and Debreu later developed and refined general equilibrium theory, forming the foundation of modern economic analysis and establishing a unified paradigm for economics—and thus for modern finance. In 1952, Markowitz published his seminal paper "Portfolio Selection," founding Modern Portfolio Theory and marking the birth of modern finance. Later, Modigliani and Miller created the MM Theorem, launching the field of corporate finance as a key branch. In the 1960s, Sharpe and Lintner built and expanded the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). In the 1970s, Ross developed Arbitrage Pricing Theory (APT) based on no-arbitrage principles—a more generalized model. Also in the 1970s, Fama formally articulated the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), while Black, Scholes, and Merton developed the Option Pricing Model (OPM). By then, modern finance had become a logically rigorous discipline with a unified analytical framework.

Yet, extensive empirical studies in the 1980s revealed numerous anomalies unexplained by modern finance. To address these, some scholars applied cognitive psychology to investor behavior analysis. By the 1990s, this area saw an explosion of high-quality theoretical and empirical research, forming the vibrant field of behavioral finance. Matthew Rabin (Clark Prize 1999) and Nobel laureates Daniel Kahneman and Vernon Smith (2002) are leading figures who made foundational contributions to this domain.

In short: valuation models help determine intrinsic asset value, but humans are irrational. In real markets, investors exhibit various "psychological biases," leading to subjective overvaluation and undervaluation.

V. Retail Investors and Market Manipulation

With this background, we can now analyze the blockchain digital asset trading market.

Native blockchain digital assets currently lack a widely accepted valuation methodology unlike traditional stocks and bonds, making consensus on intrinsic value difficult to establish.

Valuation becomes relatively straightforward only when blockchain technology is used merely to issue tokens representing real-world assets (RWA).

The current blockchain digital asset market is dominated by retail investors whose trading behavior is highly irrational. Combined with unclear regulation, widespread market manipulation further amplifies irrational trading.

Many still fail to understand why financial markets need regulation. They argue: “If someone wants to manipulate the market, they’ll pump the price—who else will make money if there’s no pump?” Yet such market manipulation severely damages the entire market’s valuation system and fuels irrational speculation.

Consider this example: in a traditional stock market, for two companies in the same sector—Company A being excellent and Company B inferior—valuation models suggest A should command a higher valuation. VCs and private equity funds naturally invest in talented entrepreneurs, helping them grow and earning solid returns. Secondary market investors willingly buy and hold A’s stock, supporting its valuation and receiving good returns. This creates a win-win-win scenario among entrepreneurs, VCs, and investors. But what if B is manipulated—someone pumps its stock so its valuation far exceeds A’s? How does the market react? Will VCs still dare invest in quality founders (if great startups don’t guarantee returns)? Will secondary investors still buy good stocks (if junk stocks might rise even higher)? Will entrepreneurs bother building great companies (if stock prices no longer reflect quality)? This becomes a lose-lose-lose market. Over time, when effort yields no reward, the market slowly dies.

Does this sound familiar to blockchain digital asset investors? Indeed, today’s market chaos stems largely from rampant manipulation and regulatory ambiguity. When a meme coin’s market cap exceeds that of a so-called “value” coin, valuation confusion affects VC investment, discourages创业者, and impacts retail holders: if valuable projects don’t necessarily profit, why not gamble on the hottest pump? Of course, the inevitable result is collapse—it just depends on whether token holders exit while ahead.

VI. Token Utility

In summary, clear regulation for blockchain digital assets would be the biggest positive catalyst, enabling healthy industry development and creating a virtuous cycle where VCs, entrepreneurs, and secondary investors all win.

Until then, the industry remains in a dark, chaotic exploration phase—where value investing and pure speculation coexist. Some projects are clearly scams, yet heavily pumped by insiders. Some quality projects offer no utility to their tokens (e.g., UNI), leaving valuation unclear. Others have mediocre fundamentals but excellent token utility. From my perspective, preference ranking goes as follows:

-

Middling project, but strong token utility

-

Excellent project, but weak token utility

-

Scam project, but strong price momentum

Some may ask: why don’t great projects add utility to their tokens? Again, regulatory uncertainty is the root cause. Take UNI: utility often involves redistribution of benefits (buybacks or dividends), which constitutes a classic securities activity and invites strict oversight. To avoid regulation, teams naturally resort to vague concepts like "governance tokens." Ultimately, what kind of project you favor depends on your worldview—value investing vs. speculation.

VII. Capital-Driven vs. Innovation-Driven

Another hallmark of irrational markets is being "capital-driven." It's well known that crypto markets have roughly followed a four-year bull-bear cycle over the past decade, closely tied to Bitcoin’s four-year halving cycle. Why? The reason is obvious: each halving drastically reduces the amount of capital available for market manipulation.

In contrast, mature rational markets are "innovation-driven"—valuations based on how innovations elevate industries. Of course, this uplift isn't limited to efficiency gains. As I wrote in "My First Principles Thinking on Blockchain," the internet emphasizes efficiency, while blockchain networks prioritize decentralization and fairness—they aren't upgrades of one another, but rather a "complementarity of worldviews." Considering 6 billion people globally, even if only 20% value fairness, that’s still 1.2 billion users. Serving their demand for "correct worldview alignment" requires sophisticated technological innovation.

Fortunately, in the last bull cycle, we finally saw innovation-driven cases emerge—rewarding innovators, primary-market VCs, and secondary-market token holders alike, offering the industry a chance to enter a virtuous cycle.

Many worry about macroeconomic conditions—interest rate hikes, CPI, unemployment. But AI offers insight: true innovation thrives regardless of high interest rates. Over the past two years, AI startups secured massive funding, and public market stars like Nvidia tripled their stock price within a year. This is the market rewarding innovation.

Similarly, once crypto transitions into an "innovation-driven" era, the four-year cycle will vanish, high-rate environments won’t matter, and it could enter a prolonged upward trend like AI.

Achieving this "innovation-driven" state isn’t easy. First, primary-market VCs must identify genuine innovation. Second, retail investors in secondary markets must reduce irrational behaviors. This gap between primary-market rationality and secondary-market irrationality inevitably causes disconnection. We know VCs tend to be forward-looking—but isn’t this very disconnect a form of courage? After all, they’re materially backing innovators.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News