Dethroning Validium? Rethinking Layer2 from the Perspective of Danksharding's Proposer

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Dethroning Validium? Rethinking Layer2 from the Perspective of Danksharding's Proposer

This article aims to delve into the details of Layer2 from Dankrad's perspective, further analyzing the intricacies to gain a deeper understanding of why Validium is not strictly a "Layer2."

Author: Faust, Geeker Web3

Introduction

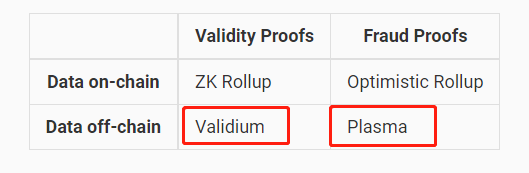

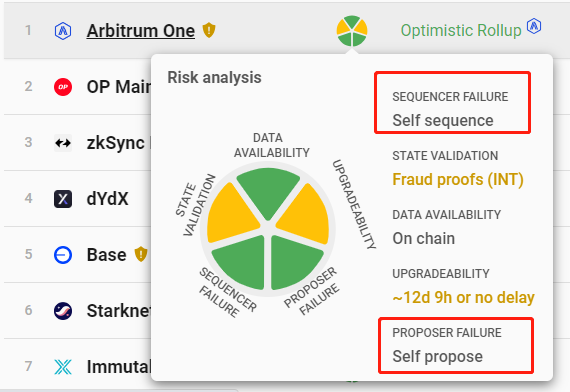

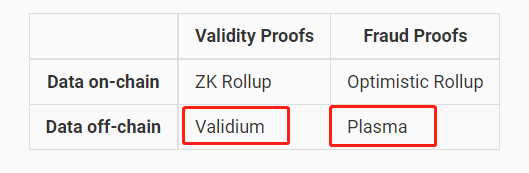

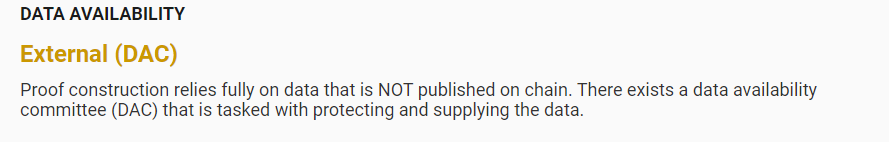

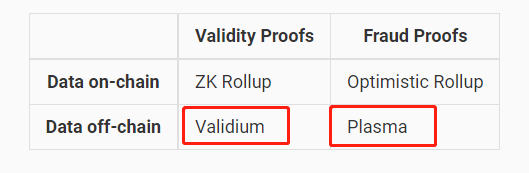

Recently, Dankrad Feist, researcher at the Ethereum Foundation and proposer of Danksharding, made a controversial statement on Twitter. He explicitly stated that modular blockchains not using ETH as their data availability (DA) layer are neither Rollups nor Ethereum Layer2 solutions. According to Dankrad’s definition, projects like Arbitrum Nova, Immutable X, and Mantle would be removed from the Layer2 list, since they publish transaction data off-chain via their own DA networks (called DACs), rather than relying on Ethereum for DA.

At the same time, Dankrad added that schemes like Plasmas and state channels—which do not require on-chain data availability to ensure security—still qualify as Layer2, but Validium (a ZKRollup that does not use Ethereum as its DA layer) does not count as Layer2.

Dankrad's comments immediately sparked criticism from several founders and researchers in the Rollup space. After all, many so-called "Layer2" projects opt not to use Ethereum as their DA layer to save costs. Removing these from the L2 category would significantly impact numerous scaling solutions. Moreover, if Validium doesn't qualify as L2, then Plasma arguably shouldn’t either.

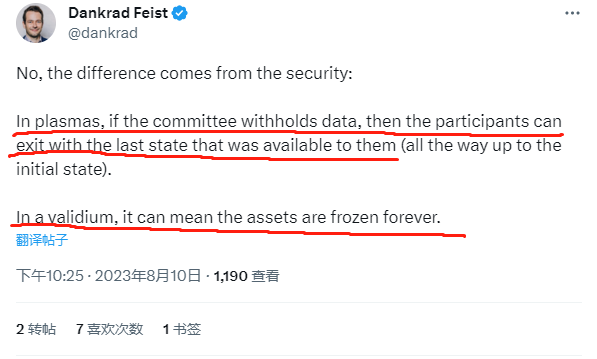

In response, Dankrad argued that when DA becomes unavailable—for instance, if the off-chain DA network withholds data—Plasma users can still securely withdraw their assets back to L1. In contrast, under the same conditions, users on Validium (most projects using StarkEx fall into this category) may be unable to withdraw funds to L1, effectively freezing their assets.

Clearly, Dankrad intends to define whether a scaling solution qualifies as an Ethereum Layer2 based on “security”. From a security standpoint, Validium indeed poses risks: in extreme scenarios where the sequencer fails and the DA layer launches a data withholding attack (hiding new data), user assets can be frozen on L2 and become unwithdrawable to L1. Although Plasma generally offers weaker security than Validium under normal circumstances, its design allows users to safely exit to L1 even during sequencer failure and DA data withholding. Thus, Dankrad’s argument holds merit.

This article aims to explore Dankrad’s perspective, diving deeper into Layer2 mechanics to understand why Validium is not strictly a “Layer2”.

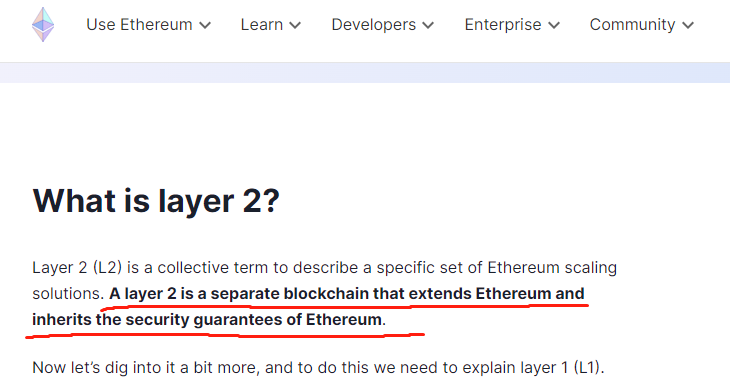

How Should We Define Layer2?

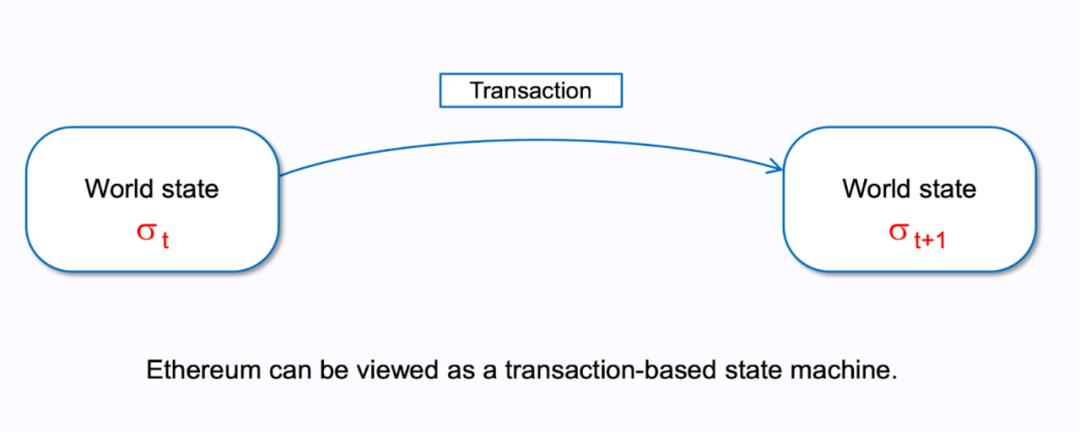

According to ethereum.org and most members of the Ethereum community, a Layer2 is an “independent blockchain that scales Ethereum while inheriting its security.” First, “scaling Ethereum” means handling traffic that Ethereum cannot process directly, alleviating TPS pressure. “Inheriting Ethereum’s security” can be rephrased as “leveraging Ethereum to ensure its own security.”

For example, all transactions (Tx) on a Layer2 must achieve final settlement on Ethereum; any incorrect transactions will be rejected. To roll back a Layer2 block, one must first roll back the corresponding Ethereum block. As long as Ethereum itself doesn’t suffer a rollback (e.g., due to a 51% attack), Layer2 blocks remain irreversible.

If we dig deeper into Layer2 security, we must also consider extreme edge cases. For instance, if the L2 team abandons the project, the sequencer fails, or the off-chain DA layer goes down, can users still securely withdraw their funds from L2 to L1?

The “Forced Withdrawal” Mechanism in Layer2

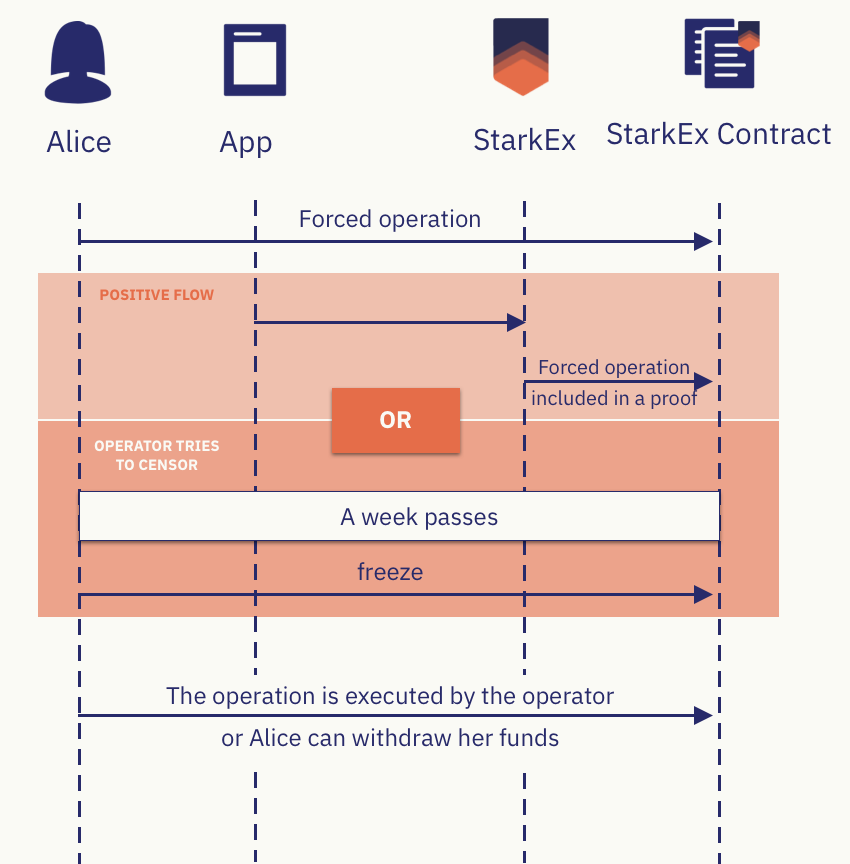

Ignoring factors such as contract upgrades or multi-sig vulnerabilities, solutions like Arbitrum and StarkEx both provide users with forced withdrawal exits. Suppose the L2 sequencer launches a censorship attack—intentionally rejecting user transactions or withdrawals—or simply shuts down permanently. Arbitrum users can invoke the forceInclusion function in the Sequencer Inbox contract on L1 to submit transaction data directly to Ethereum. If within 24 hours the sequencer fails to process this “forced inclusion” request, the transaction is automatically included in the Rollup’s transaction sequence, creating a “safe exit” for users to forcibly withdraw funds.

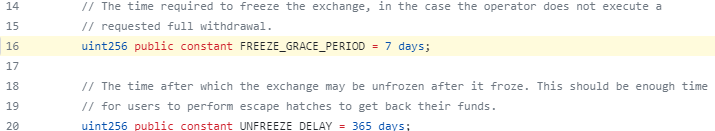

In comparison, the StarkEx solution with an Escape Hatch mechanism goes even further. If a user submits a Forced Withdrawal request on L1 and receives no response from the sequencer by the end of a 7-day window, they can trigger the freezeRequest function to put the L2 into a freeze period. During this time, the sequencer cannot update the L2 state on L1, and the frozen state lasts for one year before unfreezing.

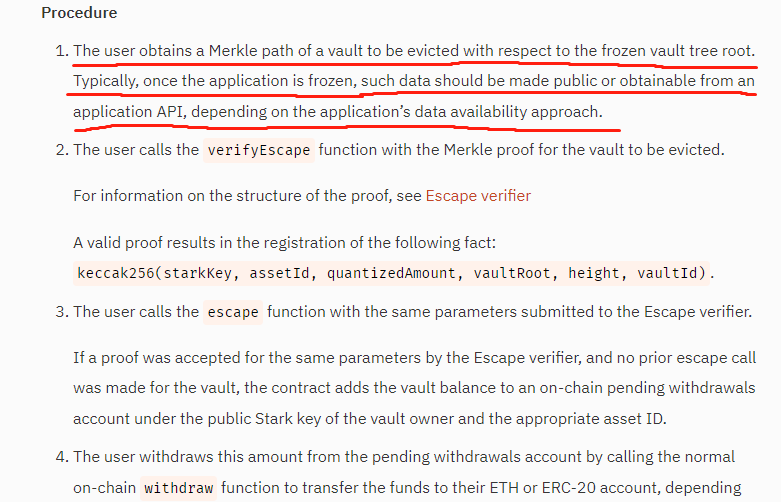

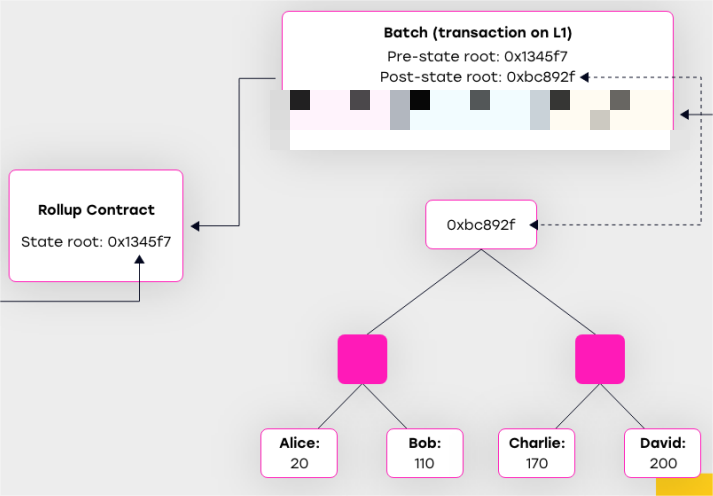

Once the L2 state is frozen, users can construct a Merkle Proof related to the current state to prove their balance on L2, and use the Escape Hatch contract on L1 to withdraw funds. This is StarkEx’s “full withdrawal” service. Even if the L2 team disappears or the sequencer fails permanently, users still have a way to extract their funds.

However, there's a catch: most L2s using StarkEx are Validium chains, which do not publish DA data on Ethereum. All information needed to reconstruct the L2 state tree remains off-chain. If users cannot access the data required to construct a Merkle Proof off-chain (e.g., if the off-chain DA layer launches a data withholding attack), they cannot initiate withdrawals through the escape hatch.

Now it becomes clear why Dankrad considers Validium insecure: because Validium does not publish DA data on-chain like Rollups, users may be unable to generate the Merkle Proofs required for forced withdrawals.

Difference Between Validium and Plasma During Data Withholding Attacks

In reality, a Validium sequencer only publishes the latest L2 Stateroot (the root of the state tree) on L1, along with a Validity Proof (ZK Proof) confirming that the state transitions (user balance changes) leading to the new Stateroot are valid.

However, the Stateroot alone cannot reconstruct the full world state trie, meaning individual account states (including balances) remain unknown. Therefore, L2 users cannot construct a Merkle Proof corresponding to the current valid Stateroot. This is the fundamental weakness of Validium.

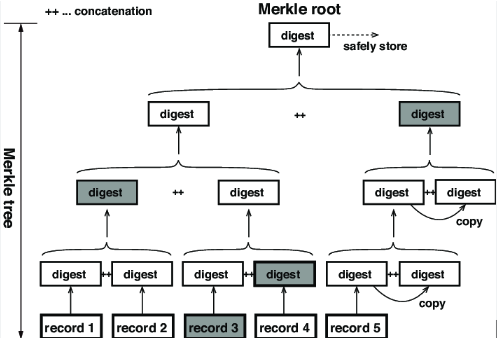

(A Merkle Proof consists of the data used in generating the root—the dark-colored parts in the diagram. To construct a Merkle Proof for a Stateroot, one must know the structure of the state tree, which requires DA data.)

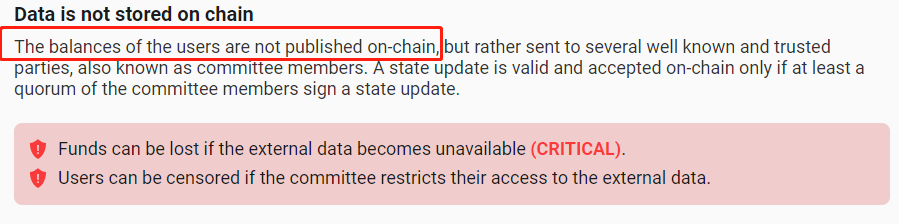

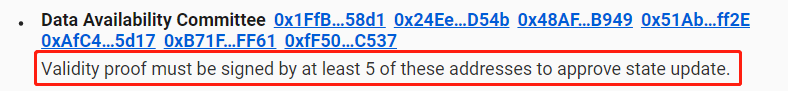

Here, we must emphasize the role of DAC. The DA data in Validium—such as the latest batch of transactions processed by the sequencer—is shared with a dedicated off-chain DA network called the Data Availability Committee (DAC). The DAC consists of multiple nodes, typically operated and supervised by the L2 team, community members, or third parties (though in practice, the actual composition of the DAC is often opaque).

Interestingly, DAC members must frequently submit multi-signatures on L1 to confirm that the new Stateroot and Validity Proof submitted by the sequencer match the DA data they’ve received. Only after the DAC’s multi-sig is submitted are the new Stateroot and Validity Proof considered valid.

Currently, Immutable X uses a 5-of-7 multi-sig DAC, while dYdX, although a ZKRollup, also has a DAC using a 1-of-2 multi-sig. (dYdX only publishes state diffs—state changes—on L1, not full transaction data. However, having access to historical state diffs allows reconstruction of all L2 account balances, enabling construction of Merkle Proofs for full withdrawals.)

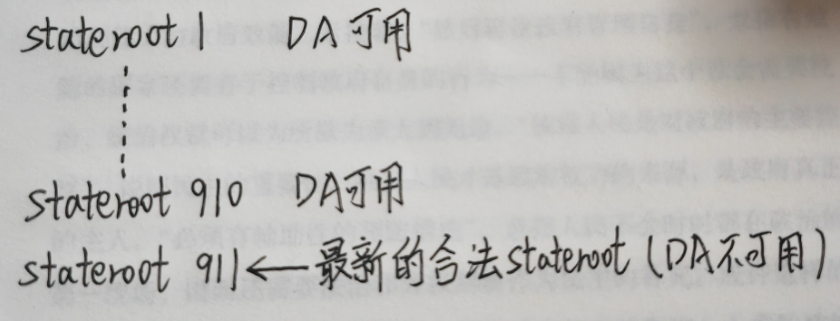

Dankrad has a point: if DAC members collude and launch a data withholding attack, preventing other L2 nodes from syncing the latest data while updating the current valid Stateroot, users cannot construct Merkle Proofs corresponding to the current valid root to withdraw funds (since post-attack DA data is unavailable, only older data remains accessible).

But Dankrad is only considering theoretical edge cases. In reality, most Validium sequencers broadcast newly processed transaction data in real-time to other L2 nodes, including honest ones. As long as even one honest node obtains the DA data promptly, users can safely exit the L2.

Why then does this theoretical vulnerability exist in Validium but not in Plasma? Because Plasma determines valid Stateroots differently from Validium—specifically, it uses a fraud proof challenge window. Plasma was an earlier L2 scaling solution, similar to Optimistic Rollups (OPR), relying on fraud proofs for security.

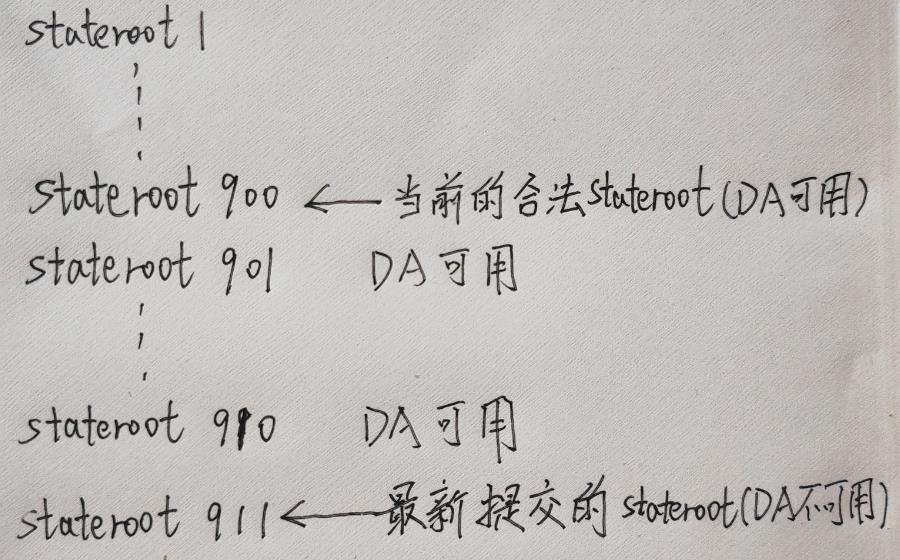

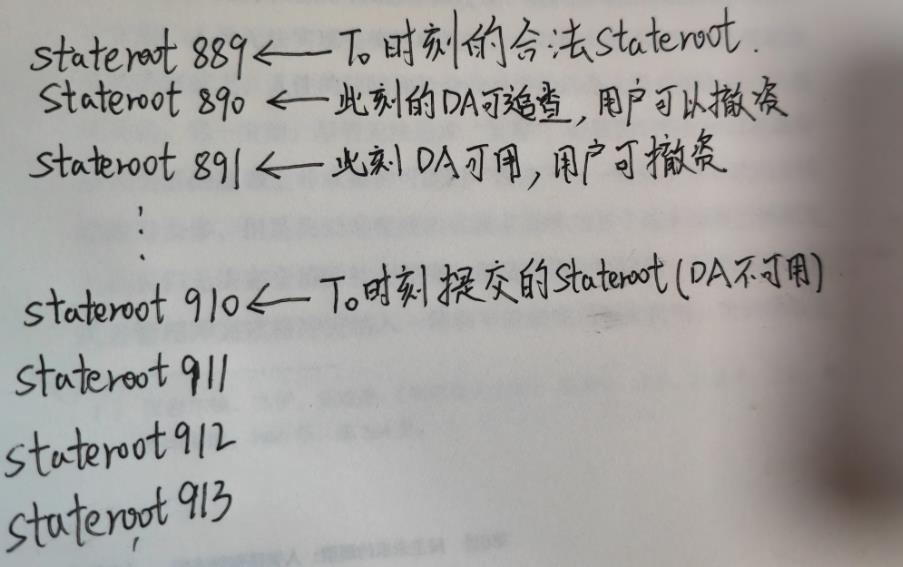

Like OPR, Plasma includes a challenge window: a newly published Stateroot is not immediately deemed valid; it must wait until the challenge period closes without any fraud proof being submitted. Thus, the current valid Stateroot in Plasma (and OPR) was submitted days ago (like starlight, what we see now was emitted long ago), and users typically can access DA data from past periods.

Additionally, the fraud proof mechanism only works if DA is currently available—that is, Plasma verifier nodes must access current DA data to generate a fraud proof if needed.

So the question simplifies: Plasma operates normally only if DA is currently available. But if DA suddenly becomes unavailable, can users still safely withdraw their funds?

This is straightforward to analyze. Suppose Plasma’s challenge window is 7 days. If starting at time T0, new DA data becomes unavailable (e.g., DAC launches a data withholding attack, blocking honest nodes from accessing data after T0). Since the valid Stateroots around T0 were submitted before T0, and historical data prior to T0 is traceable, users can still construct Merkle Proofs to initiate forced withdrawals.

Even if many users don’t notice the issue immediately, because of the challenge window (7 days for OP), as long as the Stateroot submitted at T0 hasn’t been finalized and pre-T0 DA data remains accessible, users can safely withdraw their funds from L2.

Conclusion

We can now clearly distinguish between Validium and Plasma in terms of security:

In Validium, once the sequencer publishes a Stateroot and provides a Validity Proof and DAC multi-sig, it immediately becomes valid. If users and honest L2 nodes are subjected to a data withholding attack and cannot obtain the DA data needed to construct a Merkle Proof for the current valid Stateroot, they cannot withdraw funds to L1.

In Plasma, however, a newly submitted Stateroot only becomes valid after the challenge window ends. The current valid Stateroot is therefore one submitted in the past. Due to the existence of the challenge window (3 days for ARB, 7 days for OP), even if DA data for newly submitted Stateroots becomes unavailable, users still have access to DA data for the current valid Stateroot (which is outdated), giving them ample time to force-withdraw to L1.

Therefore, Dankrad’s argument makes sense: during a data withholding attack, Validium may trap user assets on L2, whereas Plasma avoids this issue.

(One minor correction: in the image below, Dankrad incorrectly suggests Plasma allows withdrawals using outdated valid Stateroots. In practice, this could enable double-spending and is not permitted.)

Thus, data withholding attacks on off-chain DA layers introduce significant security risks. Celestia attempts to solve precisely this problem. Furthermore, since most Layer2 projects offer endpoints allowing L2 nodes to stay off-chain synced with the sequencer, Dankrad’s concerns are largely theoretical rather than practical.

If we take an extremely skeptical view and pose an even more extreme scenario—what if all off-chain Plasma nodes go down? Then ordinary users who haven’t run their own nodes couldn’t force-withdraw to L1. But the probability of such an event is equivalent to all nodes of a public blockchain collectively and permanently failing—an almost impossible occurrence.

Therefore, often we’re merely discussing things that will never happen. As the KGB deputy director tells the protagonist in the TV series *Chernobyl*: “Why worry about things that will never happen?”

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News