The Multisig and Committee Trust Risks Behind Rollup Upgrades: L2s Are Not as "Perfect" as Many Might Think

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Multisig and Committee Trust Risks Behind Rollup Upgrades: L2s Are Not as "Perfect" as Many Might Think

How to reduce the trust risks introduced by multi-sig and the security council?

Author: Linke, GeekWeb3

Introduction

Since Solana's gradual decline and the launch of OP's token, Layer2 and Rollup have seemingly become a new haven for countless Web3 practitioners. As the bear market continues to spread and with FTX collapsing and Multicoin suffering massive losses, Ethereum's competitors have gradually faded from the Web3 stage, losing their confidence to rival ETH. An increasing number of people now view Rollup as the core narrative of the next cycle, with more and more projects springing up like mushrooms on L2.

But is this all just "false prosperity," or even a "bubble ready to burst at any moment"? Are Rollups and L2s truly as wonderful as most people claim? Are they really as secure as commonly believed? Let alone the fact that many OP Rollups lack fraud proofs—what other security risks do Rollups have?

Inspired by L2BEAT’s recent report “Upgradeability of Ethereum L2s,” this article focuses on the trust risks associated with multi-sig and committee-based upgrades in Rollups, revisiting long-standing concerns about Rollups and drawing parallels with the recent Multichain incident, to comprehensively discuss why L2s are not as "ideal" as many believe.

Brief Overview of Rollup Mechanics

(If you're already familiar with how Rollups work, feel free to skip ahead)

How Rollups work:

Ethereum Rollup = A set of contracts on Layer1 + Nodes operating on its own Layer2 network.

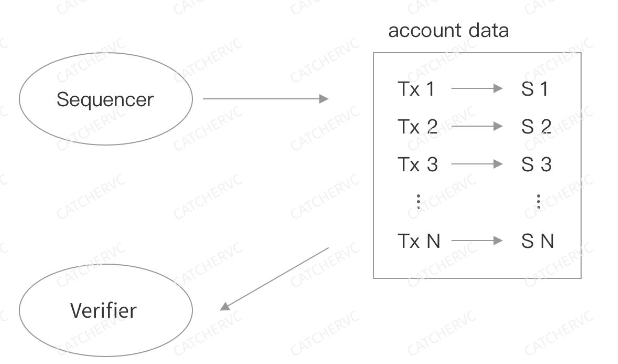

The group of Layer2 network nodes can be broken down into several roles, the most important being the Sequencer. It receives transaction requests from Layer2, determines their execution order, batches them into Batches, and sends these Batches to the Rollup project’s contract on Layer1 (hereafter collectively referred to as the Rollup Contract).

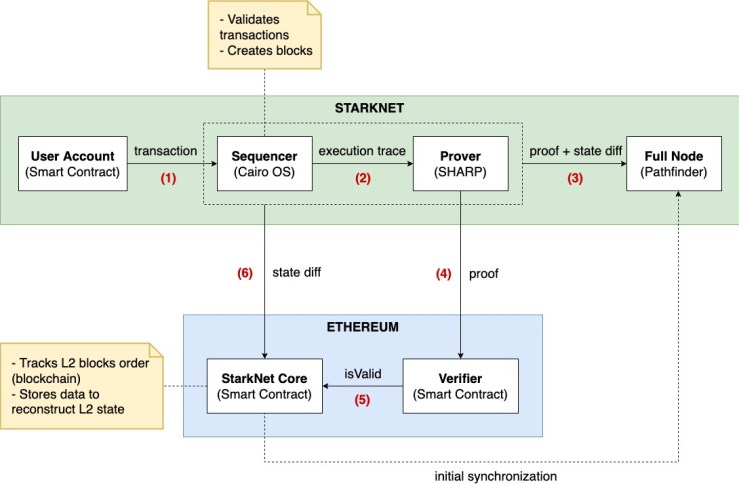

Interaction logic diagram of Starknet

Full nodes on Layer2 can directly obtain the transaction sequence from the Sequencer or read the Batches posted by the Sequencer to Layer1. However, the latter offers higher finality (immutability). Typically, once a Batch of transactions is sent to Layer1 by the Sequencer, the transaction order becomes immutable (as long as Ethereum does not experience block reorganization, the Rollup transaction sequence remains unchanged).

Since transaction execution changes the blockchain ledger state, Layer2 full nodes also need to synchronize the ledger state with the Sequencer to maintain consistency.

Therefore, the Sequencer must not only send transaction Batches to the Rollup Contract on Layer1 but also transmit the resulting state updates (Stateroot / State diff) to Layer1.

It’s clear that L1 (Ethereum) effectively acts as a bulletin board for L2 nodes, far more decentralized, trustless, and secure than the L2 network itself. For L2 full nodes, as long as they obtain the Rollup transaction sequence + initial Stateroot from L1, they can reconstruct the L2 blockchain ledger and compute the latest Stateroot. If the Stateroot calculated independently by an L2 full node differs from the one published by the Sequencer on L1, it indicates fraudulent behavior by the Sequencer.

A straightforward hypothetical scenario: Can the Sequencer on L2 steal user assets? For example, could it forge unauthorized transactions (e.g., transferring tokens from certain L2 users to the Sequencer operator’s address, then bridging those tokens to L1)? This boils down to: What happens if the Sequencer publishes incorrect transaction data or an incorrect Stateroot?

Different types of Rollups have different responses to Sequencer fraud risk. Optimistic Rollups allow L2 full nodes to submit Fraud Proofs proving the data published by the Sequencer on L1 is incorrect. For instance, Arbitrum maintains a whitelist of nodes, allowing whitelisted L2 nodes to submit Fraud Proofs.

Moreover, considering that most exchanges and private cross-chain bridge operators run L2 full nodes and can immediately detect anomalies, the success rate of a Rollup Sequencer stealing funds is essentially zero (since ultimately, stolen funds must be cashed out via exchanges or moved to L1 first).

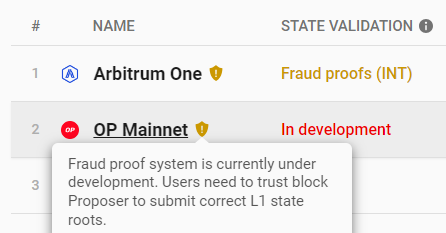

The Aggregator in the diagram is actually the Sequencer

However, for Optimism, which lacks Fraud Proofs, the Sequencer could potentially steal funds via Rollup’s native bridge contract. For example, the Sequencer operator could forge transaction instructions to transfer users’ L2 assets to their own address, then use the Rollup’s built-in bridge to move the stolen funds to L1. Without Fraud Proofs, OP’s full nodes cannot challenge invalid transactions, so theoretically, the OP Sequencer could steal user assets on L2 (if it chose to).

As of July 24, 2023, OP post-Bedrock upgrade has still not deployed its Fraud Proof system

Solutions to this problem include "social consensus" (relying on community members and social media oversight) or relying on OP’s official credibility.

Interestingly, a recent exchange reduced withdrawal delays for Arbitrum and Optimism users (from 100 L2 blocks down to 1), effectively trusting that ARB and OP Sequencers won’t act maliciously (treating them as centralized servers backed by official authority).

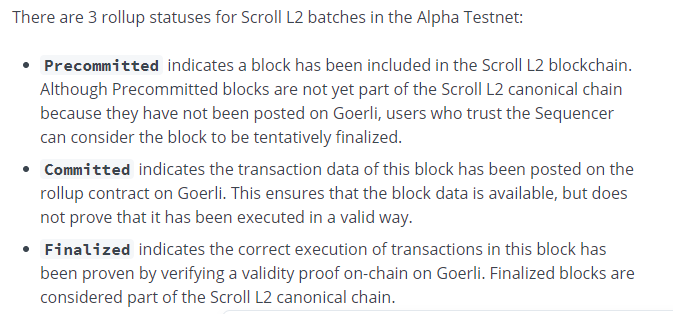

Unlike Optimistic Rollups, ZK Rollups solve the Sequencer fraud issue through Validity Proofs (often confused with ZK Proofs). Within a ZK Rollup network, there are special nodes called Provers that generate Validity Proofs for each Batch of transactions published by the Sequencer. Meanwhile, on L1, there is a dedicated contract (typically called a Verifier) that verifies these Validity Proofs. Once a Batch and its corresponding Stateroot/State diff pass verification by the Verifier contract, the transactions are finalized. The official bridge of a ZK Rollup will only approve withdrawals that have passed Validity Proof verification—clearly much more reliable than Optimism.

Scroll’s definition of three stages of transaction data

In theory, OP Rollups rely on L2 full nodes to ensure security (requiring at least one honest node capable of submitting a Fraud Proof). ZK Rollups derive their security from the Verifier contract on L1 (with final confirmation handled by L1 nodes). On the surface, both appear to "inherit L1 security" (leveraging L1 for final settlement), and Ethereum maximalists even describe it as "equivalent to L1 security" (matching L1 transaction finality). But in reality, this is far from true—indeed, extremely far.

The Long-Standing Issues

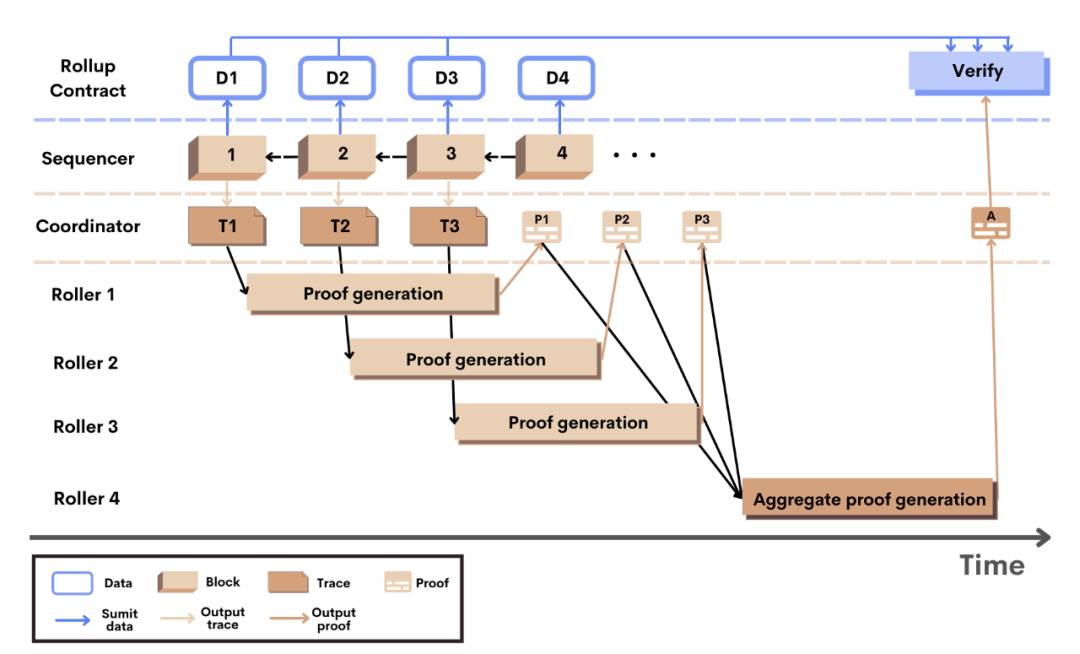

First, generating Validity Proofs in ZK Rollups is extremely slow. A Sequencer can execute thousands of transactions per second, but generating a proof for those transactions may take hours. However, this issue is relatively easy to mitigate; mainstream ZKRs typically split proof generation tasks and assign them to different Prover nodes in parallel, significantly speeding up the process.

Second, consider the latency of data publication from L2 to L1. Each time the Sequencer or Prover sends data to L1, there is a fixed cost (like needing a container for every shipment). Frequently publishing data on L1 is uneconomical or even loss-making, so Sequencers and Provers minimize publication frequency, batching large volumes of data before sending.

In other words, when user activity is low and transaction volume is insufficient, the Sequencer delays publishing data to L1. For example, during periods of low usage last year, Optimism sent transaction batches to L1 only once every half hour. Now, with increased user activity, this issue has been largely resolved. In contrast, Starknet reduces data costs by decreasing the frequency of State diff publications, resulting in finality delays of 7–8 hours.

Additionally, most ZK Rollups further reduce costs by "aggregating multiple Proofs and publishing them to L1 together." That is, the Prover doesn’t publish each Proof immediately after generation; instead, it waits until multiple Proofs are ready, aggregates them, and submits them collectively to the Verifier contract on L1. (Aggregating Proofs essentially means using one Proof to encapsulate the computational steps required to verify multiple individual Proofs.)

Scroll’s aggregated Proof diagram

The consequence is further reduced Proof publication frequency and longer delays from transaction initiation to final confirmation.

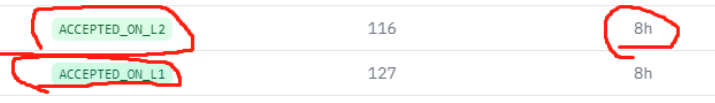

According to block explorers, Polygon ZKEVM has confirmation delays of about 30–50 minutes, while Starknet and zkSync Era exceed 7 hours. Clearly, this only represents "partial inheritance of L1 security," falling far short of the claimed "equivalence to L1 security" touted by Ethereum supporters.

Of course, these issues can be resolved through technological advancement in the near future. Many teams are developing high-performance hardware to shorten Validity Proof generation time; Optimism has promised to soon release its Fraud Proof system; and Ethereum’s Danksharding proposal will reduce Rollup data costs by tens of times or more, effectively addressing the listed problems.

The Unsolvable Problem of Human Governance

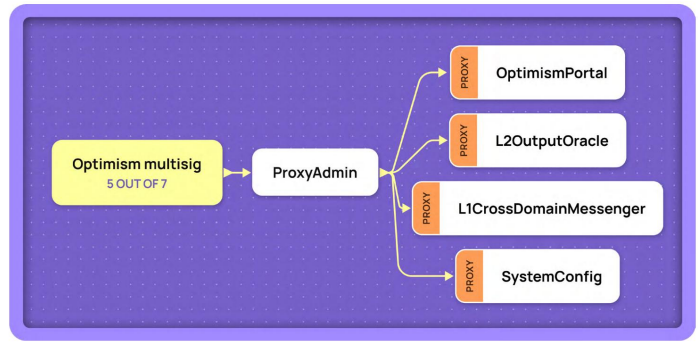

Like DeFi and other application-layer projects, Rollup networks depend on smart contracts on L1, and these contracts are often "upgradeable"—meaning parts of the code can be replaced (most Rollups use proxy contracts) and updated instantly under multi-sig or security committee authorization. To cut to the chase: A Rollup can allow a small group controlling a multi-sig or committee to quickly alter contract code on L1 and steal user assets.

Source: L2BEAT research report

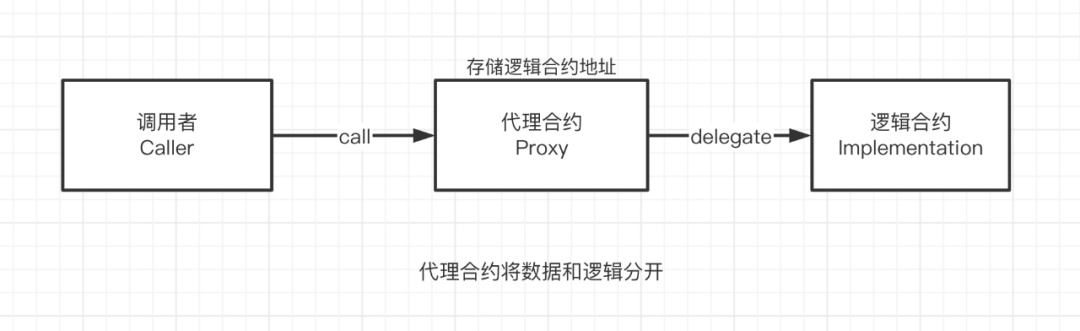

First, why do "Rollup contracts need upgrades" and "how are they upgraded?" Smart contract code on Ethereum is immutable once deployed. However, Rollups inevitably contain bugs during development that could lead to errors; they frequently iterate and add new features; and in extreme cases, might face hacker attacks. Therefore, Rollup contracts require upgradeability, typically achieved via proxy contracts.

Source: WTF Academy

Proxy contracts are a common technique in Ethereum development, separating contract data and business logic into different contracts. Data (state variables) reside in the proxy contract, while logic (functions) live in the implementation contract. The proxy contract delegates function execution entirely to the implementation contract via delegatecall, returning the result to the caller.

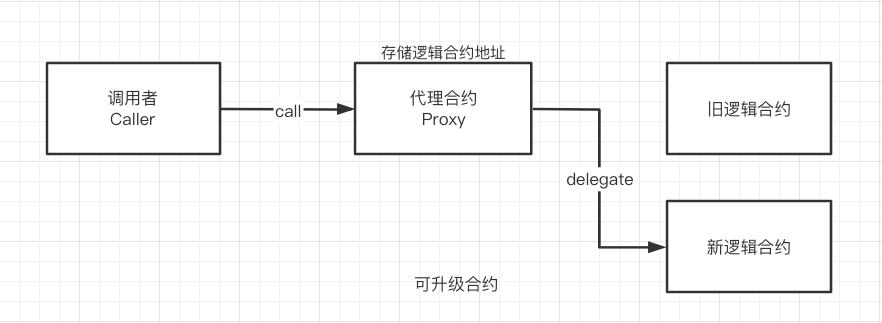

Upgrading a contract under this model simply requires updating the proxy contract to point to a new implementation contract (changing the stored address). Most Rollup projects adopt this method—a simple and brute-force approach.

Source: WTF Academy

Unsurprisingly, the upgradeability of Rollup contracts is a major risk: If the upgraded contract contains malicious code—such as modifying withdrawal conditions in the Rollup’s native Bridge contract or altering the Verifier contract’s criteria for validating proofs—the Sequencer could steal funds (mechanics explained earlier).

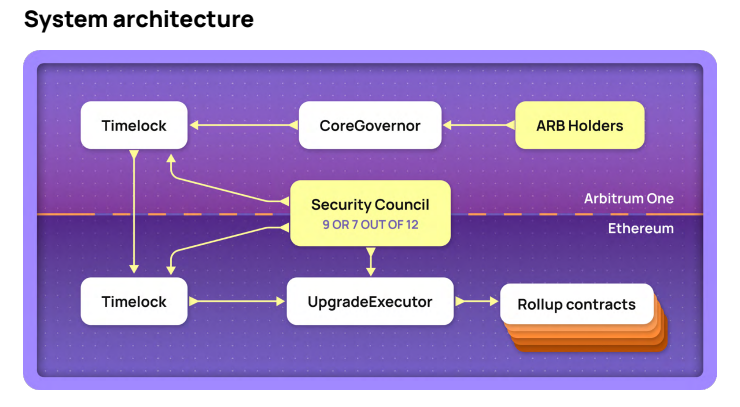

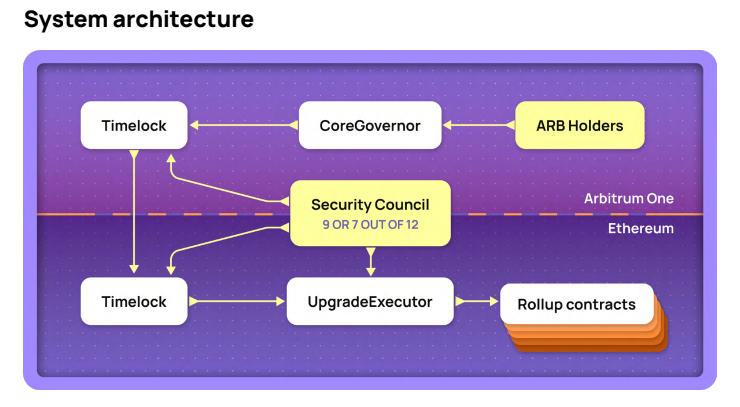

But the problem is, we can't disallow contract upgrades—the reasons were clearly stated above. As a compromise, most Rollups use DAO governance, security committees, or multi-sig approvals—essentially human governance—to decide whether to upgrade. Additionally, time locks (Timelock) are used to impose a delay window before upgrades take effect.

Source: L2BEAT research report

Given that most DAO proposals have automated execution (via on-chain contracts), upgrading a contract still requires sufficient votes and then a mandatory delay period defined by Timelock (often lasting days) before execution. Anyone attempting a malicious upgrade would need to pull off a governance attack (like what happened with Tornado Cash), which is highly costly and unlikely under normal circumstances. Even if successful, the Timelock gives users ample time to withdraw assets from L2, and the Rollup team sufficient time to take emergency action.

A time lock means certain operations are only allowed after a specified delay

Time locks seem like the ultimate safeguard against malicious upgrades. But here’s the catch: the so-called "emergency measures available to Rollup teams" actually involve bypassing DAO governance and time locks via multi-sig or security committee authorization to immediately upgrade Rollup contracts. Given that major Rollups currently manage billions of dollars in user assets, the ability to instantly upgrade contracts via multi-sig or committee serves as the ultimate emergency measure—but also as a sword of Damocles hanging over every user.

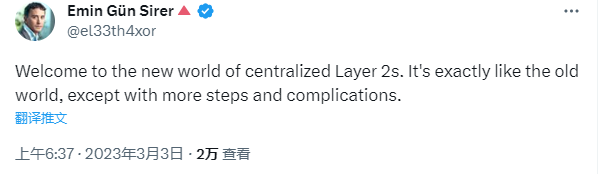

This is clearly a maximal trust problem: you must trust that the Rollup team has no intention of stealing your assets. From a trustless perspective (Nick Szabo’s viewpoint), any Rollup controlled by multi-sigs or committees is inherently insecure. Avalanche founder Emin Gün Sirer, Solana founder Anatoly, and well-known critic Justin Bons have all highlighted this issue.

Which Rollups Are Controlled by Multi-Sigs or Committees?

According to the report “Upgradeability of Ethereum L2s” and data visualization from leading L2 research firm L2BEAT, mainstream Rollups including Arbitrum, Optimism, Loopring, ZKSync Lite, zkSync Era, Starknet, and Polygon ZKEVM all have upgradeable contracts controlled by multi-sigs or committees that can bypass time lock restrictions.

dYdX has an EOA address capable of bypassing DAO governance for upgrades, but it’s still subject to a time lock (minimum 2-day delay). Immutable X has a 14-day upgrade delay. Thus, according to L2BEAT, dYdX and Immutable X are more trustless than other mainstream Rollups currently live on mainnet.

Source: L2BEAT research report

So how can we reduce the trust risks posed by multi-sigs and committees? The answer is similar to the Multichain incident: it boils down to an anti-Sybil problem. We must ensure that the multi-sig/committee consists of multiple distinct entities with minimal overlapping interests and low collusion risk. Currently, aside from improving DAO decentralization maturity and inviting reputable individuals or institutions to join the multi-sig/committee, there seems to be no better solution—an issue all too familiar in real-world democratic politics.

Of course, time locks can also be imposed on contract upgrades managed by multi-sigs/committees, but this requires balancing many factors since the very purpose of multi-sigs/committees is to handle emergencies swiftly. Moreover, if a Rollup team lacks strong commitment to trustlessness, this issue simply cannot be resolved.

Therefore, although different Rollup projects employ sophisticated mechanisms to ensure user asset safety most of the time, due to the existence of multi-sigs and committees, the probability of a black swan event in Rollups is not zero. Even if the collusion risk among multi-sig/committee members is just one in ten thousand, given the value locked in L2s (say $10 billion), the daily risk exposure for L2 users remains as high as $1 million. Recalling the Multichain incident, this is truly chilling.

Thus, in my opinion, as Polynya previously stated, most capital within the Ethereum ecosystem will still prefer circulating and staying on L1 rather than moving to L2. Rollup ecosystems will not capture the majority of value in the Ethereum ecosystem in the long term. For large holders and whales, Ethereum mainnet remains a more suitable and reliable destination than L2. So, the earlier concern—"Will the rise of L2s lead to the decline of L1?"—has already been answered.

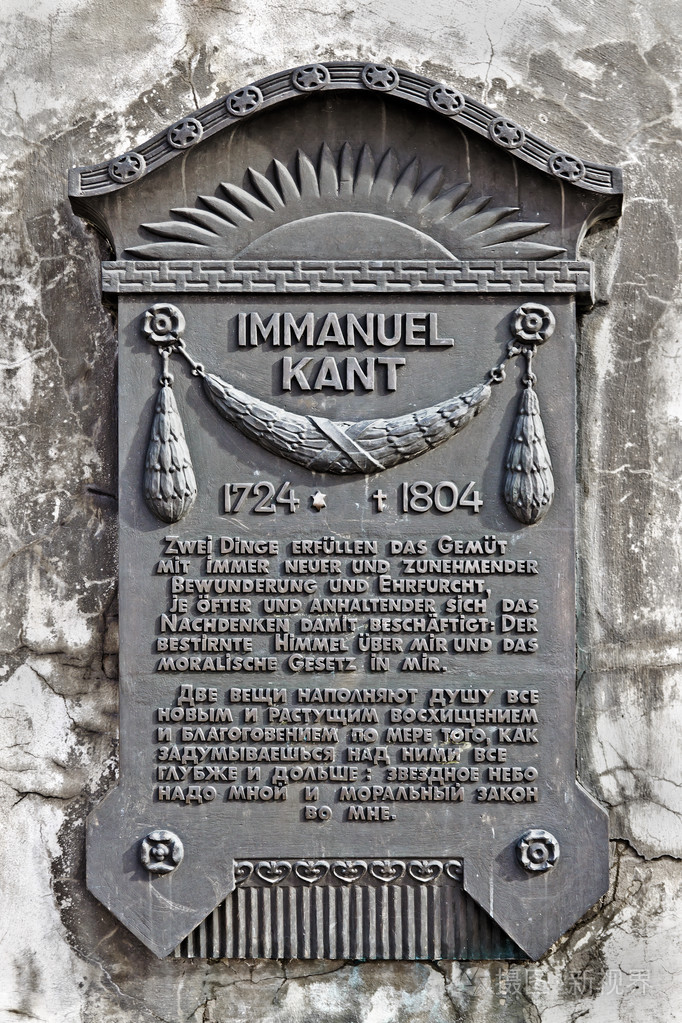

As Keigo Higashino wrote, the human heart is far more elusive, complex, and difficult to understand and change than mathematical formulas. Many things cannot be solved by technology alone. Whenever "human nature" is involved, it remains the most uncontrollable, unpredictable, and gravest issue demanding our utmost seriousness. Let us remember the timeless epitaph on Kant’s tombstone:

"Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me."

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News