Vitalik: What exactly is Danksharding?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik: What exactly is Danksharding?

Danksharding is a proposed new sharding design for Ethereum—what exactly can this technology bring?

Author: Vitalik Buterin

What is Danksharding?

Danksharding is a proposed new sharding design for Ethereum that introduces several notable simplifications compared to earlier designs.

All recent Ethereum sharding proposals since 2020 (including both Danksharding and pre-Danksharding) differ from most non-Ethereum sharding proposals primarily due to Ethereum's rollup-centric roadmap: Ethereum sharding provides space not for transactions, but for data—data that the Ethereum protocol itself does not attempt to interpret. Verifying blobs only requires checking whether the blob is available, i.e., whether it can be downloaded from the network. This data space within blobs is expected to be used by Layer 2 rollup protocols supporting high-throughput transactions.

The main innovation introduced by Danksharding is the merged fee market: instead of having a fixed number of shards, each with different blocks and different block proposers, in Danksharding there is only one proposer selecting all transactions and all data entering that slot.

To avoid imposing high system requirements on validators under this design, we introduce proposer-builder separation (PBS): a special class of participants called block builders bid for the right to choose slots, while proposers only need to select the highest valid header. Only block builders must process the entire block (here, third-party decentralized oracle protocols could also enable distributed block building); all other validators and users can efficiently verify blocks via data availability sampling (remember: the "large" part of the block is just data).

What is proto-danksharding (a.k.a. EIP-4844)?

Proto-danksharding (also known as EIP-4844) is an Ethereum Improvement Proposal (EIP) that implements most of the logic and "scaffolding" required for full Danksharding (e.g., transaction format, validation rules), but does not yet actually implement any sharding. In the proto-danksharding implementation, all validators and users still must directly verify full data availability.

The key feature introduced by proto-danksharding is a new type of transaction, which we call a "blob-carrying transaction." Blob-carrying transactions are similar to regular transactions, except they carry additional data called a blob. Blobs are very large (~125 kB) and significantly cheaper than an equivalent amount of calldata. However, EVM execution cannot access blob data; the EVM can only view commitments to the blob.

Because validators and clients still need to download the full blob content, the data bandwidth target in proto-danksharding is 1 MB per slot, rather than the full 16 MB. Nevertheless, since this data does not compete with existing Ethereum transaction gas usage, there remains substantial scalability benefit.

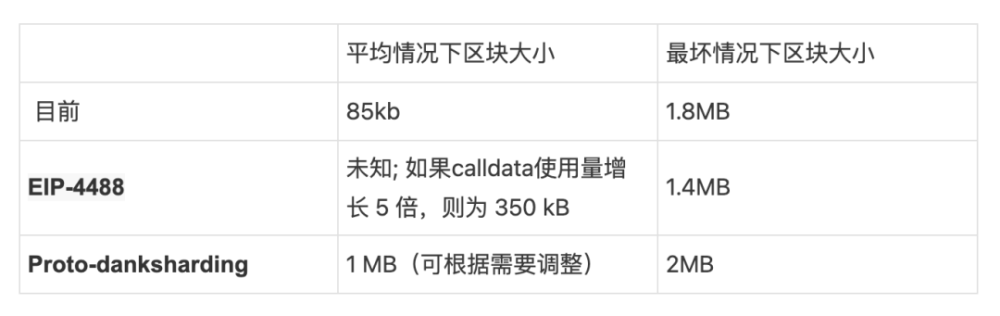

Why is adding 1 MB of data per block acceptable when everyone must download it, whereas making calldata 10 times cheaper is not?

This relates to the difference between average load and worst-case load. Today, we already experience average block sizes around 90 kB, but the theoretical maximum block size (if all 30M gas in a block were used for call data) is about 1.8 MB. The Ethereum network has previously processed blocks close to this maximum. However, if we simply reduced calldata gas costs by a factor of 10, although the average block size would increase to still acceptable levels, the worst case would become 18 MB—far too much for the Ethereum network.

The current gas pricing scheme cannot separate these two factors: the ratio between average load and worst-case load depends on user choices about how much gas to spend on calldata versus other resources, meaning gas prices must be set based on worst-case possibilities, causing average load to unnecessarily remain below what the system could handle. But if we change gas pricing to more explicitly create a multi-dimensional fee market, we can avoid the average-case/worst-case load mismatch and include data amounts per block closer to the maximum our system can safely handle. Proto-danksharding and EIP-4488 are two proposals doing exactly this.

How does proto-danksharding compare to EIP-4488?

EIP-4488 is an earlier and simpler attempt to solve the same average-case/worst-case load mismatch problem. EIP-4488 uses two simple rules:

Calldata gas cost reduced from 16 gas per byte to 3 gas per byte

Hard limit of 1 MB per block plus 300 bytes extra per transaction (theoretical maximum: ~1.4 MB)

A hard cap is the simplest way to ensure that a larger increase in average-case load doesn't lead to a proportional increase in worst-case load. The reduction in gas cost will greatly increase rollup usage, potentially increasing average block size to hundreds of KB, but the hard limit will directly prevent the worst-case possibility of including a single 10 MB block. In fact, worst-case block size would be smaller than today (1.4 MB vs 1.8 MB).

Proto-danksharding instead creates a separate transaction type that can hold cheaper data in large, fixed-size blobs, limiting how many blobs can be included per block. These blobs are not accessible from the EVM (only commitments to blobs are), and blobs are stored by the consensus layer (beacon chain) rather than the execution layer.

The main practical difference between EIP-4488 and proto-danksharding is that EIP-4488 attempts to minimize changes required today, whereas proto-danksharding makes extensive changes now so that future upgrades to full sharding require minimal further changes. Although implementing full sharding (with data availability sampling, etc.) remains a complex task even after proto-danksharding, this complexity is contained within the consensus layer. Once proto-danksharding launches, execution layer client teams, rollup developers, and users won't need to do further work to complete the transition to full sharding.

Note that the choice between the two isn't binary: we could implement EIP-4488 as soon as possible, then follow up with proto-danksharding half a year later.

Which parts of full danksharding does proto-danksharding implement, and what remains to be implemented?

Quoting EIP-4844:

Work completed in this EIP includes:

· A new transaction type whose format is exactly the same as needed in "full sharding."

· All execution-layer logic required for full sharding.

· All execution/consensus cross-validation logic required for full sharding.

· Separation between BeaconBlock validation and data availability sampling for blobs.

· Most of the BeaconBlock logic required for full sharding.

· An independently self-adjusting gas price for blobs.

Work remaining to achieve full sharding includes:

· Low-degree extension of blob_kzgs in the consensus layer to allow 2D sampling.

· Actual implementation of data availability sampling.

· PBS (proposer-builder separation), to avoid requiring individual validators to process 32 MB of data in a single slot.

· Per-validator proof of custody or similar in-protocol requirement to verify specific portions of shard data in each block.

Note that all remaining work consists of consensus layer changes, requiring no additional effort from execution client teams, users, or rollup developers.

What about all these very large blocks increasing disk space requirements?

Both EIP-4488 and proto-danksharding result in a long-term maximum usage of approximately 1 MB per slot (12 seconds). This equates to roughly 2.5 TB per year—far higher than Ethereum's current growth rate.

In the case of EIP-4488, addressing this issue requires a historical expiry scheme (EIP-4444), where clients are no longer required to store history beyond a certain period (durations from 1 month to 1 year have been proposed).

In the case of proto-danksharding, regardless of whether EIP-4444 is implemented, the consensus layer can implement separate logic to automatically delete blob data after some time (e.g., 30 days). However, regardless of which short-term data scaling solution is adopted, implementing EIP-4444 as soon as possible is strongly recommended.

Both strategies limit the additional disk burden on consensus clients to at most a few hundred GB. Long-term, adopting some form of historical expiry mechanism is essentially mandatory: full sharding would add approximately 40 TB of historical blob data per year, so users can practically store only a small fraction of it for extended periods. Thus, setting expectations early about this is valuable.

If data is deleted after 30 days, how can users access old blobs?

The purpose of the Ethereum consensus protocol is not to guarantee permanent storage of all historical data. Instead, it aims to provide a highly secure real-time bulletin board and leave room for other decentralized protocols to perform longer-term storage. The bulletin board exists to ensure data posted on it remains available long enough for any interested user or backup long-term protocol to retrieve the data and import it into their own applications or protocols.

Generally, long-term historical storage is easy. While 2.5 TB per year is too demanding for regular nodes, it's very manageable for dedicated users: you can buy very large hard drives at about $20 per TB, well within reach for hobbyists. Unlike consensus, which relies on an N/2-of-N trust model, historical storage operates on a 1-of-N trust model: you only need one honest data holder. Therefore, each piece of historical data needs to be stored only hundreds of times, rather than thousands like real-time consensus validating nodes.

Practical methods for storing and making full history easily accessible include:

Application-specific protocols (e.g., rollups) might require their nodes to store the portion of history relevant to their application. Lost historical data poses no risk to the protocol, only to individual applications, so it makes sense for applications to bear the burden of storing data relevant to themselves.

Storing historical data in BitTorrent, e.g., automatically generating and distributing a 7 GB file daily containing blob data from blocks.

The Ethereum portal network (currently under development) could easily be extended to store history.

Block explorers, API providers, and other data services may store full history.

Individual enthusiasts and academics performing data analysis might store full history. In the latter case, keeping history locally provides significant value by making direct computation easier.

Third-party indexing protocols like TheGraph may store full history.

At higher levels of historical storage (e.g., 500 TB per year), the risk of some data being forgotten increases (and data availability verification systems become more stressed). This could become the true scalability limit of sharded blockchains. However, currently proposed parameters are far from this point.

What is the format of blob data, and how is it committed?

A blob is a vector of 4096 field elements, numbers in the range:

Mathematically, a blob is treated as representing a polynomial of degree < 4096 over the finite field with the above modulus.

The commitment to a blob is a hash of the KZG commitment to this polynomial. However, from an implementation perspective, focusing on the mathematical details of the polynomial isn't important. Instead, there will simply be a vector of elliptic curve points (a trusted setup in Lagrange form), and the KZG commitment to a blob will be just a linear combination. Quoting code from EIP-4844:

BLS_MODULUS is the modulus mentioned above, and KZG_SETUP_LAGRANGE is the vector of elliptic curve points forming the trusted setup in Lagrange form. For implementers, treating this simply as a black-box specialized hash function is reasonable for now.

Why use a hash of KZG instead of KZG directly?

EIP-4844 does not use KZG directly to represent blobs, but instead uses a versioned hash: a single 0x01 byte (indicating this version) followed by the last 31 bytes of SHA256 hash of the KZG.

This is done for EVM compatibility and future-proofing: KZG commitments are 48 bytes, while the EVM naturally works with 32-byte values, and if we switch from KZG to something else (e.g., for quantum resistance), KZG commitments could continue using 32-byte outputs.

What are the two precompiles introduced in proto-danksharding?

Proto-danksharding introduces two precompiles: blob verification precompile and point evaluation precompile.

The blob verification precompile is self-explanatory: it takes a versioned hash and a blob as inputs and verifies that the provided versioned hash is indeed a valid versioned hash of the blob. This precompile is intended for use by Optimistic Rollups. Quoting EIP-4844:

Optimistic Rollups only need to provide underlying data when submitting fraud proofs. The fraud proof submission function will require the full content of the fraudulent blob as part of calldata. It will use the blob verification function to validate the data against the previously submitted versioned hash, then perform fraud proof verification on that data as today.

The point evaluation precompile takes a versioned hash, x-coordinate, y-coordinate, and proof (KZG commitment of the blob and KZG evaluation proof) as inputs. It verifies the proof to check P(x) = y, where P is the polynomial represented by the blob with the given versioned hash. This precompile is intended for use by ZK Rollups. Quoting EIP-4844:

ZK rollups will provide two commitments for their transaction or state delta data: a KZG in the blob and some commitment using whatever proof system the ZK rollup internally uses. They will use a commitment equivalence proof, using the point evaluation precompile, to prove that the KZG (which the protocol ensures points to available data) and the ZK rollup's own commitment refer to the same data.

Note that most major Optimistic Rollup designs use multi-round fraud schemes, where the final round requires only a small amount of data. Hence, it's conceivable that Optimistic Rollups could use the (much cheaper) point evaluation precompile instead of blob verification precompile—and doing so would be less expensive.

What does the KZG trusted setup look like?

See:

https://vitalik.ca/general/2022/03/14/trustedsetup.html

General description of how powers-of-tau trusted setups work

https://github.com/ethereum/research/blob/master/trusted_setup/trusted_setup.py

Example implementation of all important trusted-setup-related computations

Specifically in our case, the current plan is to run four ceremonies in parallel of sizes (n1=4096,n2=16), (n1=8192,n2=16), (n1=16834,n2=16), and (n1=32768,n2=16) (with different secrets). Theoretically, only the first is needed, but running more larger-sized ones improves future flexibility by allowing us to increase blob sizes. We can't just have a single larger setup because we need a hard limit on the degree of polynomials we can commit to, equal to the blob size.

A potential practical approach is to start from the Filecoin setup and run a ceremony to extend it. Multiple implementations, including browser-based ones, will allow broad participation.

Can't we use another commitment scheme without a trusted setup?

Unfortunately, using anything other than KZG (such as IPA or SHA256) makes the sharding roadmap significantly harder. There are several reasons:

Non-algebraic commitments (e.g., hash functions) are incompatible with data availability sampling, so if we used such a scheme, we'd have to switch to KZG anyway when moving toward full sharding.

IPA might be compatible with data availability sampling, but it leads to more complex schemes with weaker properties (e.g., self-healing and distributed block building become harder).

Neither hash nor IPA support cheap implementations of the point evaluation precompile. Thus, hash- or IPA-based implementations couldn't efficiently serve ZK Rollups or support cheap fraud proofs in multi-round Optimistic Rollups.

Therefore, unfortunately, the functional loss and increased complexity from using anything other than KZG far outweigh the risks of KZG itself. Moreover, any risk associated with KZG is contained: a KZG failure would affect only rollups and other applications relying on blob data, not the rest of the system.

How "complex" and "new" is KZG?

KZG commitments were introduced in a 2010 paper and have been widely used since 2019 in PLONK-style ZK-SNARK protocols. However, the underlying mathematics of KZG commitments is a relatively simple arithmetic built atop elliptic curve operations and pairings.

The specific curve used is BLS12-381, invented by Barreto-Lynn-Scott in 2002. Elliptic curve pairings, necessary for verifying KZG commitments, are very complex mathematically, but were invented in the 1940s and applied to cryptography since the 1990s. By 2001, numerous cryptographic algorithms using pairings had been proposed.

From an implementation complexity standpoint, KZG isn't harder to implement than IPA: the function computing commitments (see above) is identical to the IPA case, just using a different set of elliptic curve point constants. The point evaluation precompile is more complex because it involves pairing evaluation, but the math is the same as already done in EIP-2537 (BLS12-381 precompile) implementations, and very similar to bn128 pairing precompiles (see also: optimized Python implementation). Thus, implementing KZG verification doesn't require complex "new work."

What are the different software components involved in proto-danksharding implementation?

There are four main components:

1. Execution-layer consensus changes (see EIP):

New transaction type carrying blobs

Opcode outputting the i-th blob's versioned hash in the current transaction

Blob verification precompile

Point evaluation precompile

2. Consensus-layer consensus changes (see this folder in the repo):

List of blob KZGs in BeaconBlockBody

"Sidecar" mechanism where full blob contents are passed alongside BeaconBlock as a separate object

Cross-check between blob versioned hashes in the execution layer and blob KZGs in the consensus layer

3. Mempool

BlobTransactionNetworkWrapper (see network section of EIP)

Stronger anti-DoS protection to compensate for large blob sizes

4. Block building logic

Accept transaction wrappers from mempool, place transactions into ExecutionPayload, place KZGs into beacon block body and sidecar

Handling the two-dimensional fee market

Note that for a minimal implementation, we don't need a mempool at all (we could rely on Layer 2 transaction bundling markets), and we only need one client to implement block-building logic. Only the execution-layer and consensus-layer consensus changes require extensive consensus testing and are relatively lightweight. Anything between such a minimal implementation and a "full" deployment where all clients support block production and mempool is possible.

What does the proto-danksharding multi-dimensional fee market look like?

Proto-danksharding introduces a multi-dimensional EIP-1559 fee market with two resources—gas and blobs—each having separate floating gas prices and separate limits.

That is, there are two variables and four constants:

Blob fees are charged in gas, but it's a variable amount of gas that adjusts so that in the long run, the average number of blobs per block equals the target number.

The two-dimensional nature means block builders face a harder problem: instead of simply accepting transactions with the highest priority fees until they run out of transactions or hit the block gas limit, they must simultaneously avoid hitting two different limits.

Here's an example. Suppose gas limit is 70, blob limit is 40. The mempool has many transactions sufficient to fill the block, of two types (tx gas includes per-blob gas):

Priority fee 5 per gas, 4 blobs, 4 total gas

Priority fee 3 per gas, 1 blob, 2 total gas

A miner following the naive "decreasing priority fee" algorithm would fill the entire block with 10 transactions of the first type (40 gas), earning 5 * 40 = 200 gas revenue. Because these 10 transactions completely fill the blob limit, they cannot include more transactions. But the optimal strategy is to take 3 transactions of the first type and 28 of the second type. This gives a block with 40 blobs and 68 gas, earning 5 * 12 + 3 * 56 = 228 revenue.

Do execution clients now have to implement complex multi-dimensional knapsack algorithms to optimize their block production? No, for several reasons:

EIP-1559 ensures most blocks don't reach either limit, so in practice only a few blocks face the multi-dimensional optimization problem. Under normal circumstances where the mempool doesn't have enough (well-paying) transactions to reach either limit, any miner can achieve optimal revenue by including every transaction they see.

In practice, fairly simple heuristics can get close to optimal. See Ansgar's EIP-4488 analysis for some data on this.

Multi-dimensional pricing isn't even the largest source of revenue from specialization—MEV is. Specialized MEV revenue extracted via dedicated algorithms from on-chain DEX arbitrage, liquidations, front-running NFT sales, etc., constitutes a large portion of "extractable value" (i.e., priority fees): specialized MEV revenue appears to average about 0.025 ETH per block, while total priority fees are typically around 0.1 ETH per block.

Proposer-builder separation (PBS) is designed around highly specialized block production. PBS turns block construction into an auction where specialized participants bid for the privilege of creating blocks. Regular validators only need to accept the highest bid. This prevents MEV-driven economies of scale from spreading to validator centralization, but handles all issues that might make optimizing block construction more difficult.

For these reasons, the more complex fee market dynamics don't greatly increase centralization or risk; in fact, broader application of principles can actually reduce DoS attack risks!

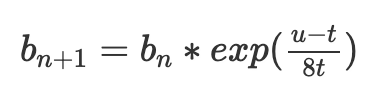

How does the exponential EIP-1559 blob fee adjustment mechanism work?

Today's EIP-1559 adjusts basefee b to achieve a specific target gas usage level t as follows:

Where b(n) is the current block's basefee, b(n+1) is the next block's basefee, t is the target, and u is the gas used.

A major problem with this mechanism is that it doesn't actually target t. Suppose we get two blocks, first u=0, next u=2t. We get:

Although average usage equals t, the basefee dropped by 63/64. So basefee only stabilizes when usage is slightly above t; in practice clearly about 3% higher, though the exact number depends on variance.

A better formula is exponential adjustment:

exp(x) is the exponential function e^x, where e≈2.71828. For small x values, exp(x)≈1+x. But it has the convenient property of being permutation-independent: multi-step adjustments depend only on the sum u1+...+un, not on the distribution. To see why, we can do the math:

Thus, including the same transactions leads to the same final basefee regardless of how they're distributed across different blocks.

The final formula above also has a natural mathematical interpretation: the term (u1+u2+...+un - n*t) can be seen as surplus—the difference between total gas actually used and total gas intended to be used.

The fact that current basefee equals

clearly shows that the surplus cannot go beyond a very narrow range: if it exceeds 8*t*60, the basefee becomes e^60—astronomically high, unpayable by anyone; if it falls below zero, resources are essentially free and the chain would be spammed until surplus returns above zero.

The adjustment mechanism works exactly along these lines: it tracks actual total (u1+u2+...+un) and computes targeted total (n*t), calculating price as the exponential of the difference. To simplify computation, instead of e^x we use 2^x; in fact, we use an approximation of 2^x: the fake_exponential function in the EIP. The fake exponential is almost always within 0.3% of the actual value.

To prevent prolonged underuse leading to prolonged 2x full blocks, we add an extra feature: we don't let surplus go below zero. If actual_total is below targeted_total, we simply set actual_total equal to targeted_total. In extreme cases (blob gas dropping all the way to zero), this does break transaction-order invariance, but the added security makes this an acceptable trade-off. Also note an interesting consequence of this multi-dimensional market: when proto-danksharding is first introduced, initially there may be few users, so for a time the cost of one blob will almost certainly be very cheap—even while "regular" Ethereum blockchain activity remains expensive.

The author believes this fee adjustment mechanism is better than the current approach and ultimately all parts of the EIP-1559 fee market should transition to using it.

For a longer, more detailed explanation, see Dankrad's post.

How does fake_exponential work?

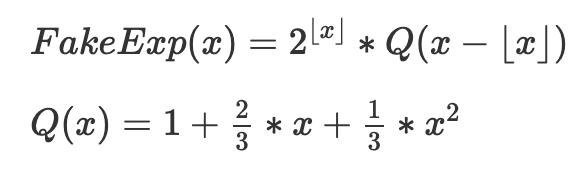

For convenience, here is the code for fake_exponential:

Here is the core mechanism re-expressed mathematically, removing rounding:

The goal is to splice together many instances of (QX), appropriately shifted and scaled for each [2^k,2^(k+1)] range. Q(x) itself is an approximation of 2^x for 0≤x≤1, chosen for these properties:

Simplicity (it's a quadratic equation)

Correctness at left edge (Q(0)=2^0=1)

Correctness at right edge (Q(1)=2^1=2)

Smooth slope (we ensure Q’(1)=2*Q’(0), so the slope of each shifted+scaled copy of Q at its right edge matches the slope of the next copy at its left edge)

The last three requirements give three linear equations for three unknown coefficients, and the Q(x) given above is the unique solution.

The approximation is surprisingly good; for all inputs except the smallest, fake_exponential gives answers within 0.3% of the actual 2^x value:

What issues in proto-danksharding are still debated?

Note: This section may easily become outdated. Don't rely on it for the latest thinking on any particular issue.

All major Optimistic Rollups use multi-round proofs, so they can use (much cheaper) point evaluation precompiles instead of blob verification precompiles. Anyone truly needing blob verification could implement it themselves: taking blob D and versioned hash h as input, choosing x=hash(D,h), computing y=D(x) using barycentric evaluation, and using the point evaluation precompile to verify h(x)=y. So do we really need the blob verification precompile, or can we just remove it and use only point evaluation?

How capable is the chain at handling persistent long-term 1 MB+ blocks? If the risk is too high, should the target blob count be reduced from the start?

Should blobs be priced in gas or ETH (burned)? Should other adjustments be made to the fee market?

Should the new transaction type be treated as a blob or an SSZ object, in the latter case changing ExecutionPayload to a union type? (This is a trade-off between "do more work now" vs "do more work later")

Exact details of trusted setup implementation (technically outside the scope of the EIP itself, as such setup is "just a constant" for implementers, but still needs to be done).

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News