Vitalik responds to Musk: Improving blockchain scalability is not simple

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik responds to Musk: Improving blockchain scalability is not simple

As capacity increases, the minimum number of nodes also increases, and so does the cost of the archive chain (if no one bothers to manage the archive chain, the risk of data loss rises).

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: Alyson

Recently, Elon Musk, founder of Tesla, tweeted that Dogecoin could "easily win" if it ideally made blocks confirm 10x faster, increased block size by 10x, and reduced fees by 100x.

This statement drew criticism from many KOLs in the crypto space. Vitalik Buterin, co-founder of Ethereum, has now written an article addressing this idea, arguing that simply increasing blockchain network parameters leads to more problems. He elaborates on the real challenges and limitations involved in scaling blockchain networks. ChainCatcher has translated the article with minor edits that do not affect the original meaning.

How far can you push blockchain scalability? Can you really achieve what Musk suggests—making block confirmation 10 times faster, increasing block size 10-fold, and reducing fees by 100 times—without causing extreme centralization and undermining the fundamental properties of blockchains? If not, how far can you go? What happens if you change the consensus algorithm? And more importantly, what changes occur when you adopt technologies like ZK-SNARKs or sharding?

It turns out there are significant and subtle technical constraints limiting blockchain scalability, whether or not sharding is used. In many cases, solutions exist, but even with them, there are limits. This article explores these issues.

1. Nodes Must Be Sufficiently Decentralized

At 2:35 AM, you receive an urgent call from your partner on the other side of the world who helps you manage your mining pool (or perhaps a staking pool). About 14 minutes ago, they started telling you that your mining pool—and a few others—has split off from the main chain, which still represents 79% of the network. According to your node, the majority chain’s blocks are invalid. There's a balance error: a key block appears to have incorrectly allocated 4.5 million extra coins to an unknown address.

An hour later, you're in a Telegram chat with two smaller mining pools. Eventually someone pastes a link to a tweet containing an announcement. The tweet begins: “Announcing a new on-chain sustainable protocol development fund.”

By morning, arguments rage across Twitter and community forums. By then, much of those 4.5 million coins have already been converted into other assets, and billions of dollars worth of DeFi transactions have taken place. 79% of consensus nodes, along with all major block explorers and light wallets, follow this new chain.

Perhaps the new developer fund will finance some developments, or maybe all the funds get absorbed by leading exchanges. Regardless, the fund becomes a de facto reality, and ordinary users are powerless to resist.

Could this happen on your blockchain? The elite in your blockchain community—mining pools, block explorers, hosted nodes—are likely well-coordinated. They probably share the same Telegram channels and WeChat groups. If they truly wanted to suddenly change protocol rules for their own benefit, they could.

The only reliable defense against such coordinated social attacks is passive resistance through actual decentralization—users running their own validating nodes.

Imagine users run nodes that automatically reject any block violating protocol rules—even if over 90% of miners or stakeholders support it. How would the story unfold? If every user ran a validating node, the attack would quickly fail: a few mining pools and exchanges might fork off, looking foolish.

Even if only some users run validating nodes, attackers won’t succeed cleanly. Instead, chaos ensues—different users see different versions of the blockchain. At minimum, ensuing market panic and potential chain splits would severely reduce attacker profits. The very prospect of navigating such a prolonged conflict deters most attacks.

Tweet by Hasu, research partner at Paradigm

If your community consists of 37 nodes running validator software and 80,000 passive listeners checking signatures and block headers, attackers win. If everyone runs a node, attackers lose. We don’t know the exact threshold for herd immunity against coordinated attacks, but one thing is clear: more nodes are better; fewer nodes are worse. We certainly need dozens, if not hundreds, of independently operated nodes.

2. Where Are the Limits of Node Performance?

To maximize the number of users who can run nodes, we focus on standard consumer hardware. Full nodes face three key limitations in processing large volumes of transactions:

-

Computation: What percentage of CPU capacity should be safely dedicated to block validation?

-

Bandwidth: Given real-world internet connections, how many bytes can a block contain?

-

Storage: How many GB of disk space can we reasonably require users to store? And how fast must it be read? (Can we use HDDs, or do we need SSDs?)

Many people mistakenly believe simple techniques can scale blockchains arbitrarily far due to overly optimistic assumptions about these figures. Let's examine each factor:

1) Computation

Wrong answer: 100% of CPU capacity can be spent on block verification.

Right answer: Around 5–10% of CPU capacity should be used for block verification.

There are four main reasons this ratio must stay low:

-

We need a safety margin to handle DoS attacks (attackers may craft transactions exploiting code weaknesses that take longer to process than normal ones);

-

Nodes need to sync quickly after going offline. If I disconnect for a minute, I should catch up within seconds;

-

Running a node shouldn't drain battery life or slow down other applications;

-

Nodes also perform non-block-production tasks, primarily verifying and responding to incoming transactions and requests over the p2p network.

Note: Until recently, most explanations for “why only 5–10%?” focused on a different issue: PoW blocks appear randomly, so long verification times increase the risk of multiple blocks being created simultaneously.

Various solutions exist (e.g., Bitcoin NG or switching to proof-of-stake), but these don’t solve the other four issues. Thus, they don’t offer nearly as much scalability gain as once hoped.

Parallelism isn't a panacea either. Even seemingly single-threaded blockchain clients often already use parallelization: one thread verifies signatures, others handle execution, and another manages mempool logic in the background. The closer you get to 100% thread utilization, the higher energy consumption and the lower the DoS safety margin.

2) Bandwidth

Wrong answer: If we have 10 MB blocks every 2–3 seconds, and most users have >10 MB/s internet, they can obviously handle it.

Right answer: Maybe we can handle 1–5 MB blocks every 12 seconds—and even that is challenging.

We often hear advertised bandwidth figures—commonly 100 Mbps or even 1 Gbps. But there’s a big gap between advertised specs and real performance due to several factors:

-

“Mbps” means “megabits per second”; a bit is 1/8th of a byte, so divide advertised bits by 8 to get bytes;

-

Like all companies, ISPs often exaggerate;

-

Multiple apps share the same connection, so nodes can’t monopolize bandwidth;

-

P2P networks inherently bring overhead: nodes frequently re-download and re-upload the same blocks (not to mention transactions broadcast via mempool before inclusion).

When Starkware experimented in 2019, releasing 500 KB blocks (made possible by lower transaction gas costs), several nodes couldn’t handle the size.

Since then, blockchain capability to handle larger blocks has improved and will continue improving. Yet no matter what we do, we remain far from naively assuming average MB/s bandwidth allows 1-second latency and massive block sizes.

3) Storage

Wrong answer: 10 TB.

Right answer: 512 GB.

As you might guess, the argument here mirrors others: theory vs practice. Theoretically, you can buy an 8 TB SSD on Amazon. Practically, the laptop I’m writing this blog post on has 512 GB. If users had to buy their own hardware, many would be lazy (or unable to afford an $800 8TB SSD) and rely on centralized providers.

Moreover, high-activity node operations can quickly wear out disks, forcing constant replacements.

Additionally, storage size determines how long it takes for a new node to join and start participating. Any data stored by existing nodes must be downloaded by new ones. Initial sync time (and bandwidth) is a major barrier to node operation. Writing this post, syncing a new Geth node took me about 15 hours.

3. Risks of Sharded Blockchains

Today, running a node on Ethereum already challenges many users. We’ve hit a bottleneck. Core developers are most concerned about storage size. Therefore, efforts to resolve computation and data bottlenecks—or even changes to consensus algorithms—are unlikely to significantly raise the gas limit. Even fixing Ethereum’s biggest known DoS vulnerability might only boost the gas limit by 20%.

The only way to solve storage bloat is statelessness and state expiry. Statelessness enables nodes to validate the chain without storing permanent state. State expiry clears infrequently accessed state, requiring users to manually renew access proofs.

Both approaches have been researched extensively, and proof-of-concept implementations for statelessness exist. Together, these improvements could greatly alleviate concerns and open room for substantially higher gas limits. Still, even after implementing both, the gas limit could likely only increase safely by about 3x before other constraints dominate.

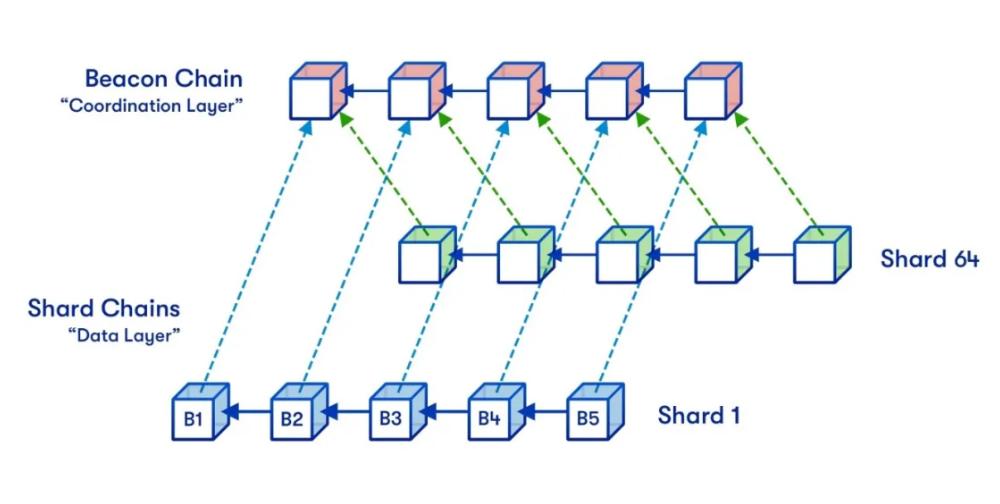

Sharding fundamentally bypasses the above limits by decoupling the data included on-chain from what individual nodes must process and store. Instead of downloading and executing blocks personally, nodes indirectly verify them using advanced math and cryptography.

Thus, sharded blockchains can securely achieve throughput levels impossible for non-sharded chains. This requires sophisticated cryptography to enable efficient, simple full validation while reliably rejecting invalid blocks—but it’s feasible. Theory is mature, and proof-of-concepts based on draft specifications are underway.

Ethereum plans quadratic sharding because nodes must handle both individual shards and the beacon chain (which performs coordination work across shards). Total scalability is thus capped by this product: if shards grow too large, nodes can’t handle one shard; if too many shards exist, nodes can’t handle beacon chain duties. Their product sets the upper bound.

One could imagine going further with cubic or even exponential sharding. Data availability sampling would become vastly more complex, but it’s theoretically possible. However, Ethereum won’t exceed quadratic scaling. The reason is that transaction sharding doesn’t yield meaningful scalability gains unless risks become prohibitively high.

So what are these risks?

1) Minimum Number of Users

A non-sharded blockchain could theoretically operate with just one user. Not so with sharded chains: no single node processes everything, so sufficient participation is required collectively. If each node handles 50 TPS and the chain needs 10,000 TPS, at least 200 nodes are needed online.

If fewer than 200 nodes exist at any point, nodes either fall behind, fail to detect invalid blocks, or experience other failures depending on software setup.

If sharded capacity increases tenfold, the minimum node count also rises tenfold. You might ask: why not start small and scale capacity as user numbers grow, reducing it if users leave? That way, we’d only use needed capacity.

But several problems arise:

-

Blockchains cannot accurately detect unique node counts, so governance would be needed to adjust shard numbers. Exceeding capacity easily causes forks and disputes.

-

What if many users unexpectedly exit?

-

Raising the minimum node requirement makes defending against hostile takeovers harder.

The minimum node count should almost certainly stay under 1,000. Hence, justifying blockchains with more than hundreds of shards seems extremely difficult.

2) Historical Data Availability

A key property users value in blockchains is permanence. Digital assets stored on company servers may vanish in 10 years when firms go bankrupt or abandon ecosystems. In contrast, NFTs on Ethereum are meant to last forever.

Yes, people will still be downloading and viewing your CryptoKitties in 2371.

But if blockchain capacity grows too high, storing all that data becomes harder. During crises, parts of history may end up with no one archiving them.

Quantifying this risk is straightforward: multiply the chain’s data capacity (in MB/s) by 30 to get annual storage in TB. Current sharding plans target ~1.3 MB/s, or ~40 TB/year. A 10x increase brings it to 400 TB/year.

For convenient access, metadata (e.g., rollup decompression data) is also needed. So we’d require ~4 PB/year, or ~40 PB over 10 years. This is a reasonable upper bound for most sharded blockchains.

Thus, in both dimensions, Ethereum’s sharding design appears close to the maximum safe threshold. Parameters could increase slightly—but not dramatically.

4. Conclusion

There are two ways to scale blockchains: fundamental technical improvements and simply increasing parameters. Increasing parameters seems attractive—back-of-the-envelope math makes it easy to believe consumer laptops can handle thousands of transactions per second without ZK-SNARKs, rollups, or sharding. Unfortunately, this approach is fundamentally flawed, for subtle reasons.

Blockchain nodes can't use 100% of CPU for validation. They need large safety margins against DoS attacks, spare capacity for mempool processing, and mustn’t make computers unusable for other tasks.

Bandwidth overhead is similar: a 10 MB/s connection doesn’t mean 10 MB blocks every second—maybe 1–5 MB every 12 seconds. Same with storage. Raising hardware requirements or restricting node operation to select participants isn’t the solution. For a decentralized blockchain, it’s vital that ordinary users can run nodes and that doing so is part of common culture.

Fundamental technical improvements do help. Currently, Ethereum’s main bottleneck is storage. Statelessness and state expiry can address this, allowing gas limits to rise safely by up to around 3x (but not 300x), making node operation easier than today. Sharded blockchains can scale further since no single node processes all transactions.

Still, limits exist: as capacity grows, so does the minimum node count, and so does archival cost (raising data loss risks if no one maintains archives).

But we needn’t worry too much: these limits are high enough to securely handle over a million transactions per second. Achieving this without sacrificing decentralization, however, will require serious effort.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News