Flying toward a $1.5 trillion IPO, Musk nearly lost it all

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Flying toward a $1.5 trillion IPO, Musk nearly lost it all

The largest IPO in human history, paving the long road to Mars.

By: Xiao Bing | TechFlow

In the winter of 2025, the sea breeze in Boca Chica, Texas remained salty and fierce, while the air on Wall Street grew unusually hot.

On December 13, a piece of news rocketed to the top of financial headlines like a Heavy Falcon launch: SpaceX's latest internal stock sale locked its valuation at $800 billion.

Memo details show that SpaceX is actively preparing for an IPO in 2026, planning to raise over $30 billion. Musk hopes the company’s overall valuation will reach $1.5 trillion. If successful, this would bring SpaceX’s market value close to the record set by Saudi Aramco during its 2019 listing.

For Musk, this is an incredibly surreal moment.

As the world's richest man, his personal wealth will once again break historical records with the launch of SpaceX—the "super rocket"—making him the first person in human history to become a trillionaire.

Turn the clock back 23 years, and no one would have believed this outcome. At that time, in the eyes of giants Boeing and Lockheed Martin, SpaceX was merely a "blue-collar manufacturer" that could be crushed at any moment.

More accurately, it resembled a disaster that just wouldn’t end.

When a Man Decides to Build Rockets

In 2001, Elon Musk turned 30.

He had just cashed out from PayPal, holding hundreds of millions in cash, standing at the classic Silicon Valley "point of life freedom." He could have done what a16z founder Marc Andreessen did—sell his company and become an investor, evangelist, or do nothing at all.

But Musk chose the most improbable path.

He wanted to build rockets—and go to Mars.

To fulfill this dream, he traveled to Russia with two friends, attempting to purchase refurbished Dnepr launch vehicles as transport for the Mars Oasis project.

The outcome was humiliating.

During meetings with Lavochkin Design Bureau, a chief Russian designer spat at Musk, believing this American nouveau riche knew nothing about aerospace technology. In the end, they quoted an exorbitant price and implied he should “get lost if he can’t afford it,” leaving the team empty-handed.

On the flight home, while his companions were dejected, Musk sat typing on his laptop. Moments later, he turned around and showed them a spreadsheet: "Hey, I think we can build it ourselves."

That year, China had just launched Shenzhou-2; spaceflight was seen as a national miracle, a game only superpowers could play. A private company building rockets seemed as laughable as a grade schooler claiming to build a nuclear reactor in their backyard.

This was SpaceX’s “from zero to one.”

Growth Is Constant Failure

In February 2002, at 1310 East Grand Avenue in El Segundo, a suburb of Los Angeles, inside a former warehouse spanning 75,000 square feet, SpaceX officially launched.

Musk invested $100 million from his PayPal proceeds as seed funding, setting the company’s vision as the “Southwest Airlines of the space industry,” offering low-cost, highly reliable space transportation services.

But reality quickly punched this idealist in the face—building rockets wasn't just hard, it was astronomically expensive.

An old saying in aerospace goes: “You can’t even wake up Boeing without ten billion dollars.”

Musk’s $100 million startup capital was a drop in the ocean. Worse still, SpaceX faced a market tightly controlled by century-old giants like Boeing and Lockheed Martin—firms not only technically powerful but deeply entrenched in government networks.

They were used to monopolies, used to massive government contracts. Toward SpaceX, the intruder, they had only one attitude: amusement.

In 2006, SpaceX’s first rocket, “Falcon 1,” stood on the launch pad.

This name paid homage to DARPA’s Falcon program and subtly referenced the Millennium Falcon from Star Wars. It looked small, even shabby—like an unfinished prototype.

As expected, 25 seconds after liftoff, the rocket exploded.

In 2007, the second launch failed too—after a few minutes of flight, it lost control and crashed.

Scoffing poured in. One comment cut deep: “Does he think rockets are software? Can you patch them?”

In August 2008, the third launch failure was the most devastating—one stage collided with the second, turning a newly ignited hope into debris scattered across the Pacific sky.

The atmosphere shifted completely. Engineers began losing sleep, suppliers demanded cash payments, media coverage turned hostile. Most critically, the money was nearly gone.

2008 was the darkest year of Musk’s life.

A global financial crisis swept through, Tesla teetered on bankruptcy, his wife of ten years left him… SpaceX’s funds were enough for only one final launch. If the fourth attempt failed, SpaceX would dissolve on the spot, and Musk would lose everything.

Then came the sharpest blow of all.

Musk’s childhood idols—“first man on the moon” Armstrong and “last man on the moon” Cernan—publicly expressed complete skepticism toward his rocket plans. Armstrong bluntly said, “You don’t understand what you’re talking about.”

Recalling those days later, Musk’s eyes welled with tears on camera. He didn’t cry when rockets blew up, nor when the company nearly went bankrupt—but he cried when mentioning his idols’ mockery.

Musk told the host: “These people were my heroes. It was really hard. I truly wish they could see how difficult my work is.”

At that moment, a subtitle appeared: Sometimes, your idol lets you down. (Sometimes the very people you look up to, let you down.)

Pull Back from the Brink

Before the fourth launch, no one talked about Mars anymore.

The entire company was wrapped in solemn silence. Everyone knew this Falcon 1 was funded by their last pennies. If this failed, the company would shut down.

On launch day, there were no grand declarations or passionate speeches—just a group of people standing silently in the control room, staring at screens.

September 28, 2008—rocket ignition. A fiery dragon lit up the night sky.

This time, the rocket didn’t explode. But the control room stayed silent until nine minutes later, when the engine shut down as planned and its payload reached orbit.

“It worked!”

Thunderous applause and cheers erupted in the control center. Musk raised both arms high. His brother Kimbal, standing beside him, burst into tears.

Falcon 1 made history—SpaceX became the world’s first privately-funded commercial space company to successfully launch a rocket into orbit.

This success didn’t just save SpaceX—it earned the company long-term “life support.”

On December 22, Musk’s phone rang, marking the end of his cursed 2008.

William Gerstenmaier, NASA’s head of space operations, delivered great news: SpaceX secured a $1.6 billion contract for 12 round-trip cargo missions between Earth and the International Space Station.

“I love NASA,” Musk blurted out—and changed his computer login password to “ilovenasa.”

Having walked the edge of death, SpaceX survived.

Jim Cantrell, who early on participated in SpaceX rocket development—and once lent Musk his university rocketry textbooks—reflected on Falcon 1’s success with deep emotion:

“Elon Musk succeeded not because he was visionary, not because he was exceptionally intelligent, not because he worked tirelessly—though all are true. The most crucial element of his success is this: his dictionary has no word for failure. Failure simply does not exist in his thinking.”

Making Rockets Come Back

If the story ended here, it would be just an inspiring legend.

But the truly astonishing part of SpaceX begins now.

Musk insisted on a seemingly irrational goal: Rockets must be reusable.

Nearly all internal experts opposed it—not because it was technically impossible, but because it was commercially too radical, like “no one recycles disposable paper cups.”

But Musk persisted.

He argued that if airplanes were discarded after each flight, no one could afford to fly. If rockets cannot be reused, space travel will forever remain a game for the few.

This was Musk’s foundational logic—first principles reasoning.

Back to the beginning: Why did a programmer-turned-entrepreneur dare to build rockets himself?

In 2001, after reading countless technical books, Musk created an Excel spreadsheet breaking down every cost component of rocket manufacturing. His analysis revealed that traditional aerospace giants had artificially inflated rocket costs by dozens of times.

These well-funded giants lived comfortably in a “cost-plus” zone, where even a screw cost hundreds of dollars. Musk asked: “How much do raw materials like aluminum and titanium actually cost on the London Metal Exchange? Why does making them into parts increase the price a thousandfold?”

If costs were artificially inflated, they could be artificially reduced.

Guided by first principles, SpaceX embarked on a path with almost no retreat.

Launch repeatedly, analyze failures, then fail again, keep trying recovery.

All doubts ceased on that winter night.

December 21, 2015—a date destined to enter human spaceflight history.

The Falcon 9 rocket, carrying 11 satellites, launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Ten minutes later, a miracle happened—the first-stage booster returned successfully and landed vertically at the Florida landing site, just like in a sci-fi movie.

In that moment, the old rules of the aerospace industry shattered completely.

The era of affordable space access was ushered in by this once-derided “underdog” company.

Building Starship with Stainless Steel

If rocket reusability was SpaceX’s challenge to physics, then building Starship with stainless steel was Musk’s “dimensional strike” against engineering orthodoxy.

In the early stages of developing Starship—the vehicle meant to colonize Mars—SpaceX initially fell into the “high-tech material” myth. Industry consensus held that to reach Mars, rockets must be lightweight, thus requiring expensive, complex carbon fiber composites.

Accordingly, SpaceX invested heavily in giant carbon fiber winding molds. But slow progress and soaring costs alerted Musk. Returning to first principles, he ran the numbers:

Carbon fiber cost $135 per kilogram and was extremely difficult to process. Meanwhile, 304 stainless steel—the same material used in kitchenware—cost only $3 per kilogram.

“But stainless steel is too heavy!”

In response to engineers’ concerns, Musk pointed out an overlooked physical truth: melting point.

Carbon fiber has poor heat resistance and requires thick, costly thermal tiles. Stainless steel melts at 1,400 degrees Celsius and gains strength under the ultra-cold conditions of liquid oxygen. When factoring in the weight of insulation systems, a rocket built with “clumsy” stainless steel ended up with a total system mass comparable to carbon fiber—but at 1/40th the cost!

This decision freed SpaceX entirely from the constraints of precision manufacturing and exotic aerospace materials. They no longer needed clean rooms—just pitch a tent on a Texas field and weld rockets like water towers. If one exploded, they’d sweep up the pieces and start welding again the next day.

This first-principles mindset has run throughout SpaceX’s entire evolution. From questioning “Why can’t rockets be reused?” to “Why must space materials be expensive?” Musk consistently starts from basic physical laws to challenge industry assumptions.

“Using commodity-grade materials to build top-tier engineering” is SpaceX’s core competitive advantage.

Starlink Is the Real Game-Changer

Technological breakthroughs drove explosive valuation growth.

From $1.3 billion in 2012, to $400 billion in July 2024, to today’s $800 billion—SpaceX’s valuation has truly “launched like a rocket.”

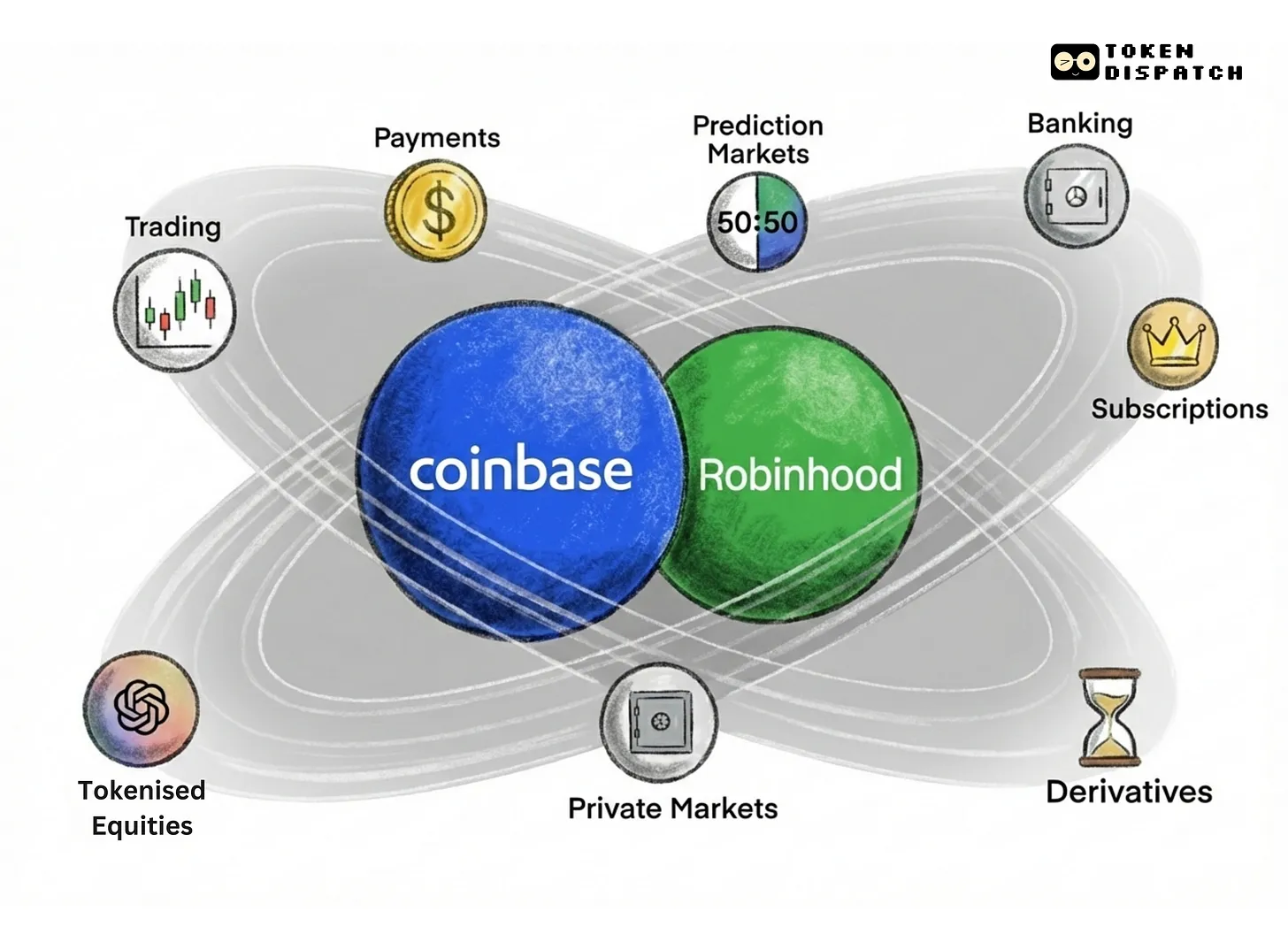

But what actually supports this astronomical valuation isn’t rockets—it’s Starlink.

Before Starlink, SpaceX was, to ordinary people, just occasional spectacular footage in the news—sometimes exploding, sometimes landing.

Starlink changed everything.

This constellation of thousands of low-orbit satellites is becoming the world’s largest internet service provider, transforming “space” from a spectacle into infrastructure as essential as water and electricity.

Whether aboard a cruise ship in the middle of the Pacific or in war-torn ruins, as long as you have a pizza-box-sized receiver, signals rain down from hundreds of kilometers above in low Earth orbit.

It hasn’t just reshaped global communications—it’s also become a super cash-printing machine, generating continuous cash flow for SpaceX.

As of November 2025, Starlink had 7.65 million active subscribers globally, with actual usage exceeding 24.5 million. North America contributed 43% of subscriptions, while emerging markets like South Korea and Southeast Asia accounted for 40% of new users.

This is why Wall Street dares to assign SpaceX such a sky-high valuation—not because rockets launch frequently, but because of the recurring revenue from Starlink.

Financial data shows SpaceX is expected to generate $15 billion in revenue in 2025, surging to $22–24 billion in 2026, with over 80% coming from Starlink.

This means SpaceX has undergone a stunning transformation—from a contract-dependent aerospace contractor to a global telecom giant with a monopoly-level moat.

On the Eve of IPO

If SpaceX successfully raises $30 billion in its planned IPO, it will surpass Saudi Aramco’s $29 billion fundraising in 2019, becoming the largest IPO in history.

Some investment banks predict SpaceX’s final IPO valuation could even reach $1.5 trillion, potentially challenging Saudi Aramco’s 2019 record of $1.7 trillion and placing it among the top 20 most valuable public companies globally.

Beneath these astronomical figures, the first to erupt in excitement are the employees at Boca Chica and Hawthorne factories.

In recent internal stock sales, shares priced at $420 mean engineers who once slept on factory floors alongside Musk and endured countless “production hells” will become millionaires—or even billionaires—overnight.

But for Musk, the IPO is far from a conventional “cash-out exit”—it’s an expensive refueling.

Previously, Musk strongly opposed going public.

At a 2022 SpaceX company meeting, Musk poured cold water on employee expectations, warning them not to dream of an IPO: “Going public is absolutely an invitation to suffering, and stock prices will only be a distraction.”

Three years later, what changed his mind?

No matter how grand the ambition, it needs capital backing.

According to Musk’s timeline, within two years, the first Starship will conduct an unmanned Mars landing test; within four years, human footprints will mark the red soil of Mars. His ultimate vision—establishing a self-sustaining city on Mars within 20 years via 1,000 Starships—will still require unimaginable sums of money.

In multiple interviews, he stated plainly: The sole purpose of accumulating wealth is to make humanity a “multiplanetary species.” Viewed this way, the hundreds of billions raised through IPO amount to Musk collecting an “interstellar toll” from Earthlings.

We look forward with anticipation: The largest IPO in human history will not turn into yachts or mansions—they will all become fuel, steel, and oxygen, paving the long road to Mars.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News