Interpreting BitVM: How to Verify Fraud Proofs on the BTC Chain? (Executing EVM or Other VM Opcodes)

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Interpreting BitVM: How to Verify Fraud Proofs on the BTC Chain? (Executing EVM or Other VM Opcodes)

BitVM does not require on-chain data; it is first published and stored off-chain, with only the Commitment stored on-chain.

Authors: Wuyue & Faust, Geeker Web3

Advisor: Kevin He, Founder of BitVM Chinese Community, ex Web3 Tech Head@Huobi

Introduction: Currently, Bitcoin Layer2 has become a growing trend, with dozens of projects on the market self-identifying as "Bitcoin Layer2." Among them, many label themselves as "Rollups" and claim to adopt the approach outlined in the BitVM whitepaper, making BitVM a prominent topic within the Bitcoin ecosystem.

Unfortunately, most existing written materials about BitVM fail to explain its underlying principles in an accessible way.

This article is our simplified summary after reading the mere 8-page BitVM whitepaper and researching related topics such as Taproot, MAST trees, and Bitcoin Script. To aid reader comprehension, some of our explanations differ slightly from those in the original BitVM whitepaper. We assume readers have some understanding of Layer2 systems and grasp the basic idea of "fraud proofs."

In short, BitVM's core idea: No need to put data on-chain; publish and store it off-chain first, placing only a Commitment (cryptographic hash) on-chain.

When a challenge or fraud proof occurs, we bring only the necessary data on-chain and prove its association with the on-chain Commitment. Then, the BTC mainnet verifies whether this on-chain data contains errors and whether the data producer (the node processing transactions) has acted maliciously. All of this follows Occam’s Razor—“Entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity” (minimize on-chain operations wherever possible).

Main text: A plain-language summary of the so-called BitVM-based fraud proof verification scheme on BTC:

1.The Core Idea of BitVM

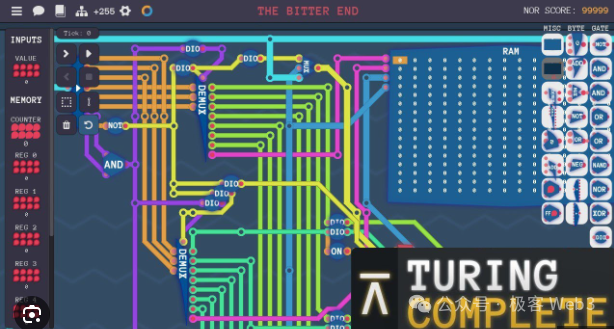

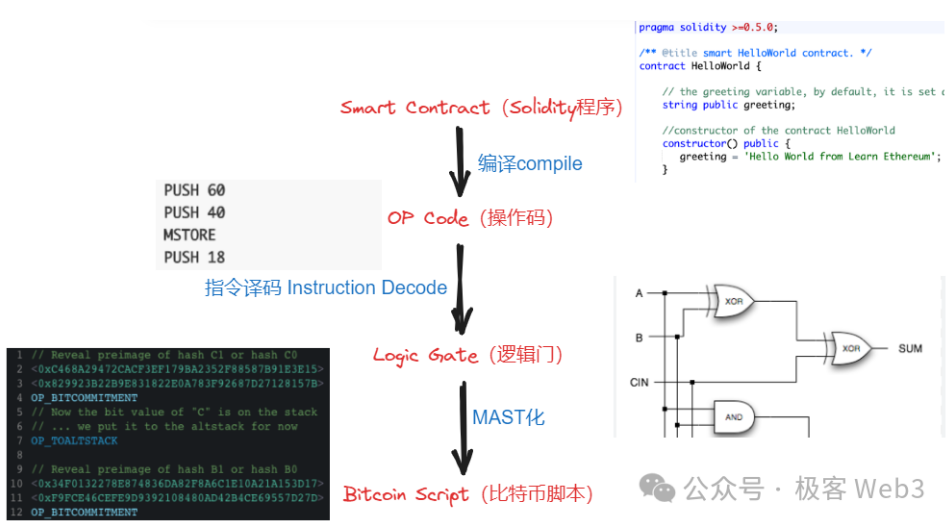

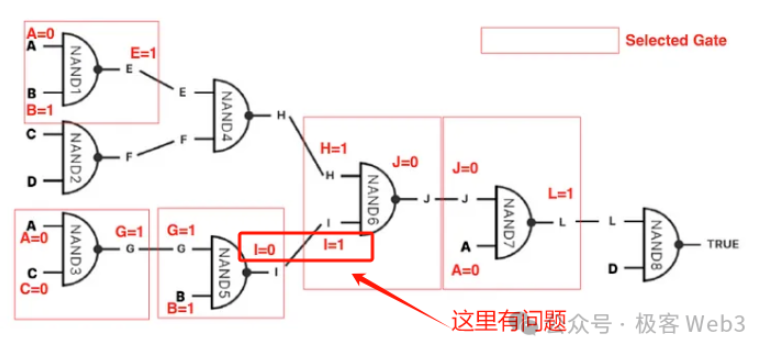

First, a computer or processor is essentially an input-output system composed of numerous logic gates. One of BitVM’s central ideas is to use Bitcoin Script to simulate the input-output behavior of logic gates.

If logic gates can be simulated, then theoretically, a Turing machine can be implemented, enabling any computable task. In other words, given enough people and money, one could assemble engineers to use the limited Bitcoin Script language to first simulate logic gates, then build up massive circuits to replicate EVM or WASM functionality.

(Screenshot from an educational game called "Turing Complete," whose core mechanic involves building a full CPU processor using logic gates, especially NAND gates)

Some compare BitVM’s approach to building an M1 processor in Minecraft using redstone circuits—or constructing the Empire State Building out of toy blocks.

(Reportedly, this is a "processor" someone built inside Minecraft after a year of work)

2. Why Simulate EVM or WASM Using Bitcoin Script?

Isn’t this overly complicated? Yes—but most Bitcoin Layer2 solutions aim to support high-level languages like Solidity or Move, while the only language natively executable on Bitcoin is Bitcoin Script, a primitive, stack-based, non-Turing-complete language made of unique opcodes.

(Example of Bitcoin Script code)

If a Bitcoin Layer2 wants to verify fraud proofs directly on Layer1—just like Arbitrum does on Ethereum—to inherit BTC’s security, it must re-execute disputed transactions or opcodes on the Bitcoin chain. This leads to the key problem:

Use Bitcoin Script—the native but limited programming language of Bitcoin—to emulate the behavior of EVM or other virtual machines.

From a compiler theory perspective, BitVM translates EVM/WASM/JavaScript opcodes into Bitcoin Script opcodes, using logic gate circuits as an intermediate representation (IR) between “EVM opcode → Bitcoin Script opcode.”

(The BitVM whitepaper discusses the general idea of executing certain "disputed instructions" on the Bitcoin chain)

Ultimately, the goal is to process instructions that normally run on EVM/WASM directly on the Bitcoin chain. While feasible, the challenge lies in expressing all EVM/WASM opcodes through vast combinations of logic gates—an enormous engineering effort for complex operations.

3. The “Interactive Fraud Proof” Highly Similar to Arbitrum

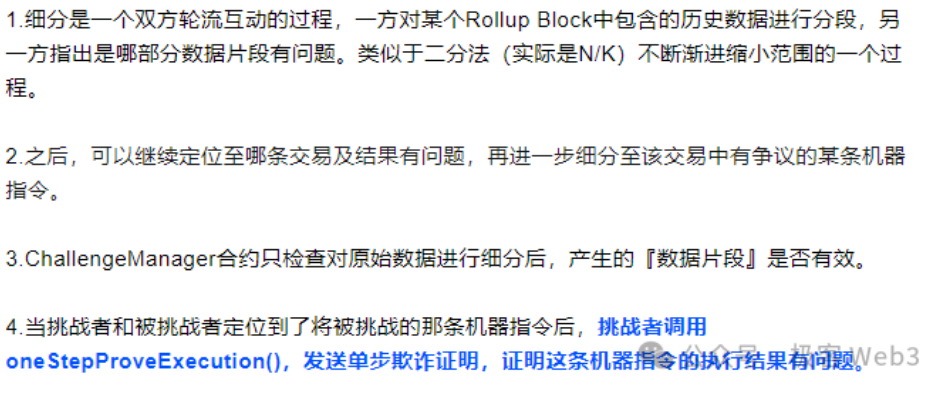

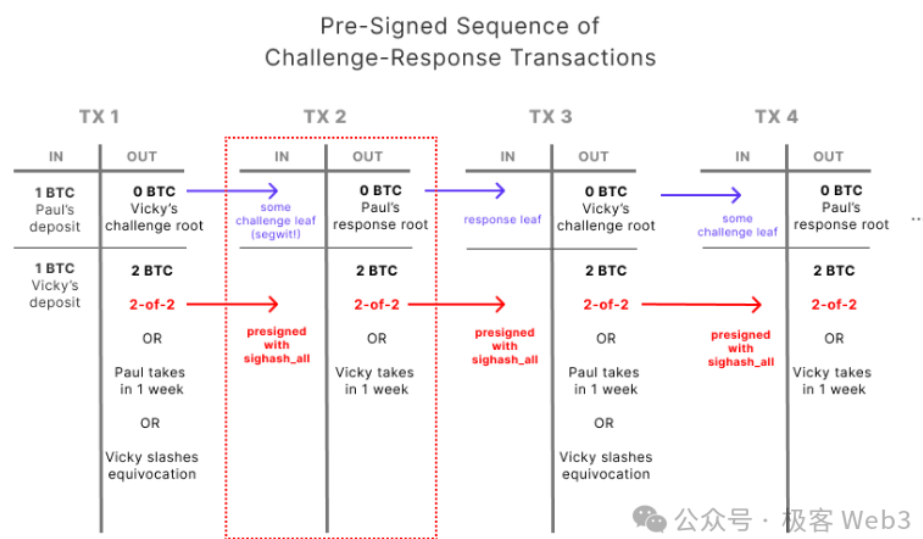

Next, we discuss another core concept from the BitVM whitepaper: the “interactive fraud proof,” which closely resembles the model used by Arbitrum.

Interactive fraud proofs involve a term called “assert.” Typically, the Layer2 proposer (often played by the sequencer) posts an assertion on Layer1, declaring that certain transaction data or state transitions are valid and correct.

If someone believes the proposer’s assertion is incorrect (i.e., the associated data is invalid), a dispute arises. At this point, the Proposer and Challenger exchange messages in rounds, performing a binary search over the disputed data to quickly isolate a single granular instruction and its associated data segment.

For this disputed instruction (OP Code), both the instruction and its input parameters must be executed directly on Layer1, and the output result verified (Layer1 nodes compute the expected output and compare it against the Proposer’s previously published result). In Arbitrum, this is known as a “one-step proof.”

(In Arbitrum’s interactive fraud proof protocol, a binary search is performed over the data published by the Proposer to rapidly locate the disputed instruction and execution result, followed by submitting a one-step proof to Layer1 for final validation)

Reference: Former Arbitrum Tech Ambassador Explains Arbitrum’s Component Architecture (Part 1)

(Diagram of Arbitrum’s interactive fraud proof process—somewhat crude explanation)

At this stage, the idea behind one-step proofs becomes clear: the vast majority of Layer2 transaction instructions do not need to be re-verified on the BTC chain. Only when challenged does a specific disputed data fragment or opcode get replayed on Layer1.

Verification outcomes:

- If the Proposer’s previously published data is found invalid, their staked assets are slashed;

- If the Challenger is wrong, their staked assets are slashed;

- If the Proposer fails to respond to a challenge in time, they may also be slashed.

Arbitrum implements these mechanisms via Ethereum smart contracts, whereas BitVM relies on Bitcoin Script features such as timelocks and multi-signature schemes.

4. MAST Trees and Merkle Proofs

After briefly explaining “interactive fraud proofs” and “one-step proofs,” we now turn to MAST trees and Merkle Proofs.

As mentioned earlier, the BitVM scheme avoids putting large volumes of Layer2 transaction data or massive logic gate circuits directly on-chain. Instead, only minimal data or circuit fragments go on-chain when absolutely necessary.

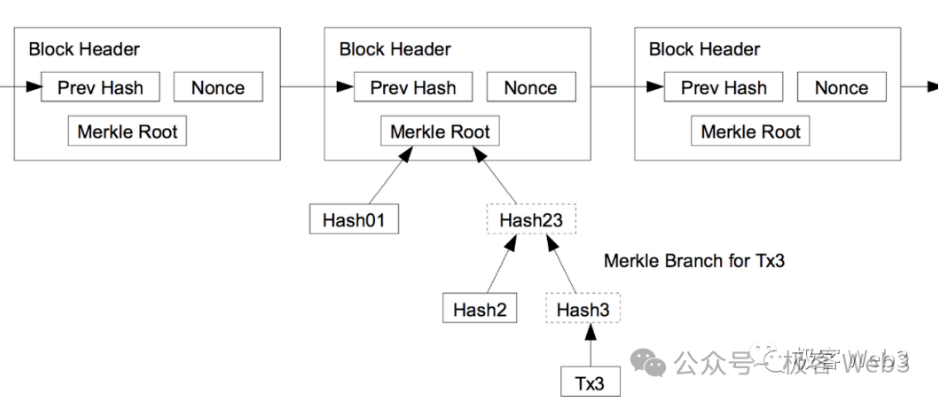

However, we need a way to prove that the data being brought on-chain was not fabricated—it must have existed off-chain beforehand. This is known as a Commitment in cryptography. Merkle Proof is one form of Commitment.

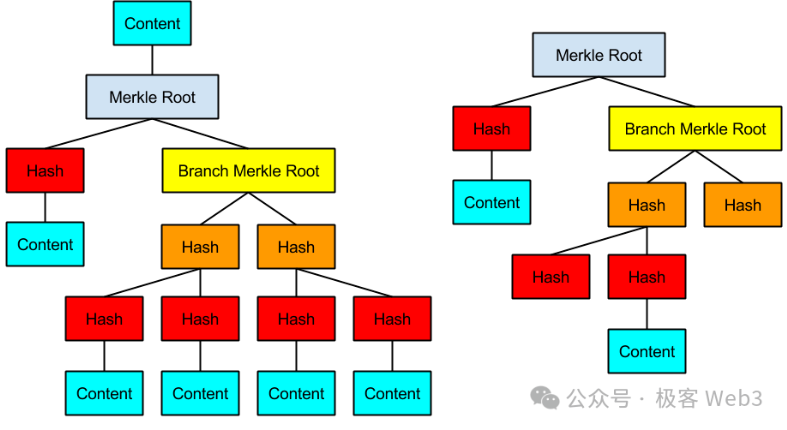

Let’s start with MAST trees. MAST stands for Merkelized Abstract Syntax Tree—a transformation of ASTs from compiler theory into Merkle Trees.

What is an AST? Its full name is “Abstract Syntax Tree.” Simply put, it breaks down complex instructions via lexical analysis into fundamental operation units, organizing them into a tree-like data structure.

(A simple example of an AST: this tree decomposes operations like x=2, y=x*3 into low-level opcodes and data)

A MAST tree takes an AST and converts it into a Merkle Tree format to support Merkle Proofs. One advantage of Merkle Trees is efficient “data compression.” For instance, if you want to later publish a specific data segment from the tree to the BTC chain and prove it genuinely belongs to the tree (not fabricated), what can you do?

You simply record the Merkle Root on-chain upfront. Later, by presenting a Merkle Proof, you can demonstrate that a given data segment exists within the Merkle Tree corresponding to that Root.

(Relationship between Merkle Proof/Branch and Root)

Thus, instead of storing the entire MAST tree on-chain, only its Root needs to be disclosed as a Commitment. When needed, revealing just the data fragment plus the Merkle Proof/Branch suffices. This drastically reduces on-chain data size while ensuring authenticity. Moreover, publishing only partial data and proofs—not everything—enhances privacy.

Reference: Data Withholding and Fraud Proofs: Why Plasma Doesn't Support Smart Contracts

(Example of a MAST tree)

The BitVM approach attempts to express all logic gate circuits using Bitcoin scripts, then organizes them into a massive MAST tree, where each leaf node (Content in the diagram) corresponds to a logic gate implemented in Bitcoin Script.

The Layer2 Proposer frequently publishes the MAST tree’s Root on the BTC chain. Each MAST tree corresponds to a transaction, encompassing all its input parameters, opcodes, and logic gates. In a sense, this is analogous to how an Arbitrum Proposer publishes Rollup Blocks on Ethereum.

When a dispute arises, the challenger declares on-chain which Root they are contesting and demands the Proposer reveal part of the data under that Root. The Proposer then provides Merkle Proofs, gradually disclosing small segments of the MAST tree on-chain until both parties narrow down to the disputed logic gate. Slash penalties can then be enforced.

(Source: Medium)

5. Finally

By now, we’ve covered the most essential aspects of the BitVM proposal. Though some details remain obscure, readers should now grasp the essence and core insights of BitVM.

Regarding the bit value commitment mentioned in the whitepaper, it prevents the Proposer from assigning conflicting values ("both 0 and 1") to a logic gate’s input during on-chain verification when challenged, thereby avoiding ambiguity.

Summary

The BitVM approach expresses logic gates using Bitcoin Script, uses those gates to represent EVM/other VM opcodes, uses opcodes to model any transaction processing flow, and finally structures everything into a Merkle Tree / MAST Tree.

Such a tree, representing complex transaction logic, could easily exceed 100 million leaves. Hence, minimizing the block space used by Commitments and limiting the scope of fraud proofs is crucial.

Although one-step fraud proofs require only tiny amounts of data and script on-chain, the complete Merkle Tree must be stored off-chain long-term, ready to be accessed during challenges.

Each Layer2 transaction generates a large Merkle Tree, implying significant computational and storage burdens on nodes. Most users may be unwilling to run full nodes (though historical data could eventually expire; B^2 Network introduces zk-storage proofs similar to Filecoin to incentivize long-term archival).

However, optimistic Rollups based on fraud proofs don’t require many nodes—security relies on the 1/N trust model: as long as at least one of N nodes is honest and willing to submit a fraud proof when needed, the Layer2 network remains secure.

Still, designing Layer2 solutions based on BitVM faces many challenges, such as:

1) Theoretically, to further compress data, instead of verifying opcodes directly on Layer1, their execution could be compressed into a zk-proof, allowing challengers to dispute steps within the proof verification. This would greatly reduce on-chain data volume, though implementation details would be highly complex.

2) The Proposer and Challenger must interact repeatedly off-chain. Designing this protocol efficiently—and optimizing Commitment handling and challenge procedures—requires substantial engineering effort.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News